Fundamentals

That feeling of profound imbalance, the sense that your body’s internal wiring is frayed after a long period of heavy alcohol use, is a direct reflection of a deep biological reality. Your experience is valid. It originates within the body’s master control network, the endocrine system.

This intricate web of glands and hormones orchestrates everything from your energy levels and mood to your reproductive health and stress responses. Alcohol acts as a pervasive disruptor to this finely tuned communication system, creating static on lines that require crystal-clear signals to function.

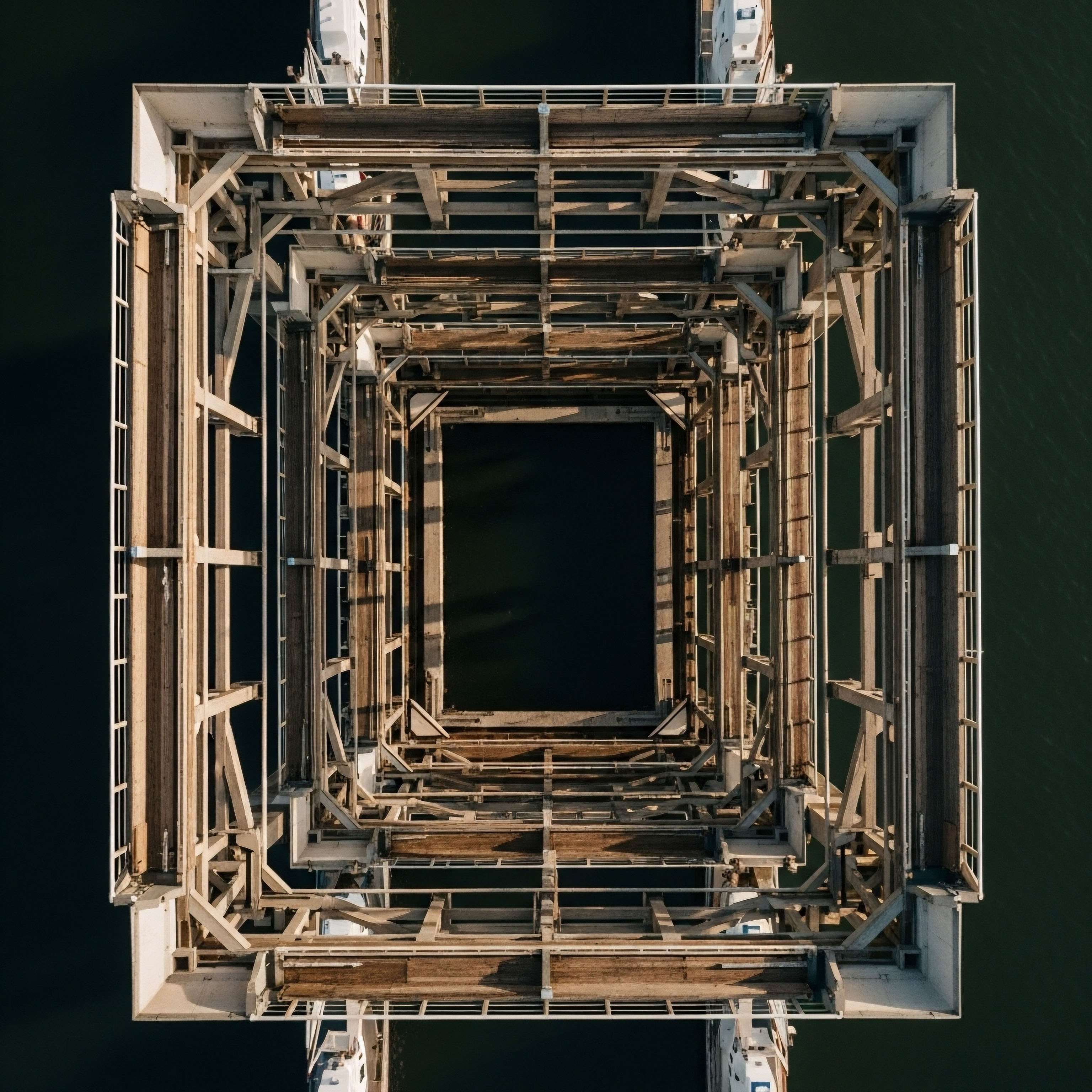

Two primary communication pathways bear the brunt of this disruption. The first is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, the command chain that governs sexual health and reproductive function. In men, this system regulates testosterone production; in women, it manages the menstrual cycle.

The second is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, our central stress response Meaning ∞ The stress response is the body’s physiological and psychological reaction to perceived threats or demands, known as stressors. system. It dictates the release of cortisol, the hormone that prepares us for “fight or flight.” Long-term alcohol exposure systematically degrades the integrity of both these circuits, leading to a cascade of symptoms that can feel both overwhelming and deeply personal.

The Communication Breakdown

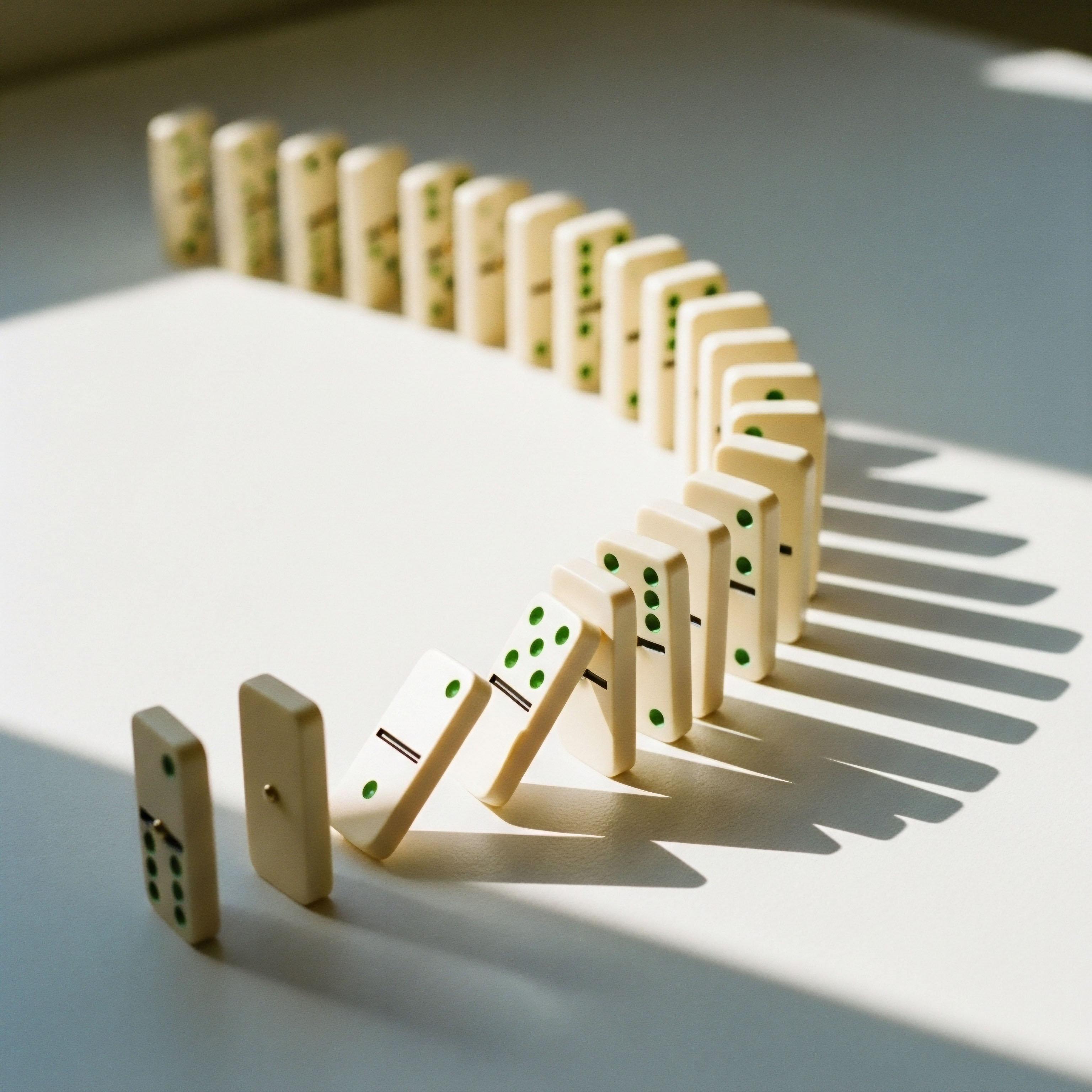

Think of your endocrine system Meaning ∞ The endocrine system is a network of specialized glands that produce and secrete hormones directly into the bloodstream. as a global logistics network, with hormones acting as precise delivery instructions sent from central command centers (the hypothalamus and pituitary gland) to specific factories (like the testes, ovaries, and adrenal glands). Alcohol is the system-wide computer virus that corrupts these messages at every stage.

It can garble the initial command from the hypothalamus, interfere with the relay at the pituitary, and directly damage the machinery within the destination factory. The result is a state of hormonal miscommunication, where signals are weakened, misinterpreted, or sent at the wrong times, leaving you with the tangible, physical consequences of a system in disarray.

Chronic alcohol use systematically interferes with the body’s essential hormonal communication pathways, leading to tangible health consequences.

Your Body’s Response to Systemic Stress

The persistent elevation of the stress hormone cortisol is one of the most significant consequences of long-term alcohol use. Your body is kept in a state of high alert, a biological emergency that never truly ends. This sustained stress signal diverts resources away from crucial long-term projects like tissue repair, immune function, and healthy digestion.

The fatigue, poor sleep, and persistent anxiety you may feel are direct physiological echoes of a body struggling to cope with an unrelenting stress signal. Understanding this connection is the first step in recognizing that these symptoms are not a personal failing, but a predictable biological response to a specific chemical stressor.

This initial understanding moves the conversation from one of self-blame to one of biological inquiry. The question becomes less about “what is wrong with me?” and more about “what has happened to my body’s systems, and how can I begin to restore their function?” This shift in perspective is the foundation upon which a journey toward reclaiming your vitality is built.

Intermediate

To comprehend the depth of alcohol’s impact, we must examine the specific ways it sabotages the key hormonal axes. The damage is multifaceted, affecting both the production of hormones and how the body responds to them. This creates a complex clinical picture where symptoms of low testosterone in men or menstrual irregularities in women are intertwined with the pervasive effects of chronic stress and metabolic dysfunction.

How Does Alcohol Disrupt Male Hormonal Balance?

In men, chronic alcohol consumption Meaning ∞ Alcohol consumption refers to the ingestion of ethanol, a psychoactive substance found in alcoholic beverages, into the human physiological system. wages a multi-front war on the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. The consequences extend far beyond simple testosterone suppression. Alcohol directly poisons the Leydig cells in the testes, the primary sites of testosterone production.

Simultaneously, it dampens the signaling from the brain; the hypothalamus produces less gonadotropin-releasing hormone (LHRH), and the pituitary, in turn, releases less luteinizing hormone (LH). LH is the critical signal that tells the Leydig cells Meaning ∞ Leydig cells are specialized interstitial cells within testicular tissue, primarily responsible for producing and secreting androgens, notably testosterone. to make testosterone. With a damaged factory and a weak command signal, testosterone output plummets.

Furthermore, alcohol accelerates the conversion of testosterone into estrogen. It achieves this by increasing the activity of an enzyme called aromatase, which is particularly active in the liver. Liver function, often compromised by heavy drinking, further exacerbates this issue. This dual effect of supressed testosterone and elevated estrogen creates a state of hormonal imbalance that drives symptoms like reduced libido, erectile dysfunction, muscle loss, fatigue, and even gynecomastia (the development of male breast tissue).

| Hormone/Marker | Healthy Profile | Chronic Alcohol User Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Testosterone |

Optimal levels, supporting libido, muscle mass, and energy. |

Significantly decreased due to testicular toxicity and suppressed pituitary signals. |

| Luteinizing Hormone (LH) |

Pulsatile release, signaling testes to produce testosterone. |

Suppressed by alcohol’s effect on the hypothalamus and pituitary. |

| Estradiol |

Low, balanced ratio with testosterone. |

Elevated due to increased aromatase activity and impaired liver metabolism. |

| Cortisol |

Follows a natural daily rhythm, peaking in the morning. |

Chronically elevated, disrupting sleep, promoting anxiety, and causing metabolic issues. |

The HPA Axis the Engine of Chronic Stress

The body’s stress response system, the HPA axis, is designed for acute, short-term threats. Alcohol forces it into a state of chronic activation. Regular, heavy drinking leads to persistently high levels of cortisol. This sustained elevation has profound consequences. It degrades sleep quality, particularly by suppressing deep, restorative slow-wave sleep.

It promotes a state of anxiety and agitation, as the body is biochemically locked in a stress response. Moreover, high cortisol levels encourage the storage of visceral fat, particularly around the abdomen, which is a significant risk factor for metabolic diseases like type 2 diabetes.

Alcohol-induced hormonal damage is a story of both direct cellular toxicity and systemic communication failure.

The Question of Reversibility

Can this damage be undone? The answer is conditional. Research indicates that some aspects of the hormonal disruption Meaning ∞ Hormonal disruption refers to a state where the endocrine system’s normal function is impaired, leading to altered hormone synthesis, secretion, transport, binding, action, or elimination. are functional and can be reversed with complete abstinence. Studies have shown that in non-cirrhotic men, testosterone levels can begin to recover, and the circadian rhythm of its release can be restored within weeks of stopping alcohol consumption.

This suggests that the direct suppressive effect on the HPG axis Meaning ∞ The HPG Axis, or Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis, is a fundamental neuroendocrine pathway regulating human reproductive and sexual functions. can be lifted. However, the potential for full recovery depends on the duration and severity of the alcohol abuse. Years of direct toxic damage to the testes and nervous system can lead to structural changes that may not be fully reversible.

The recovery of the HPA axis Meaning ∞ The HPA Axis, or Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis, is a fundamental neuroendocrine system orchestrating the body’s adaptive responses to stressors. is also a gradual process, requiring time for the system to recalibrate its baseline stress response. Therefore, while significant improvement is possible, the concept of complete “reversal” is optimistic and highly individual.

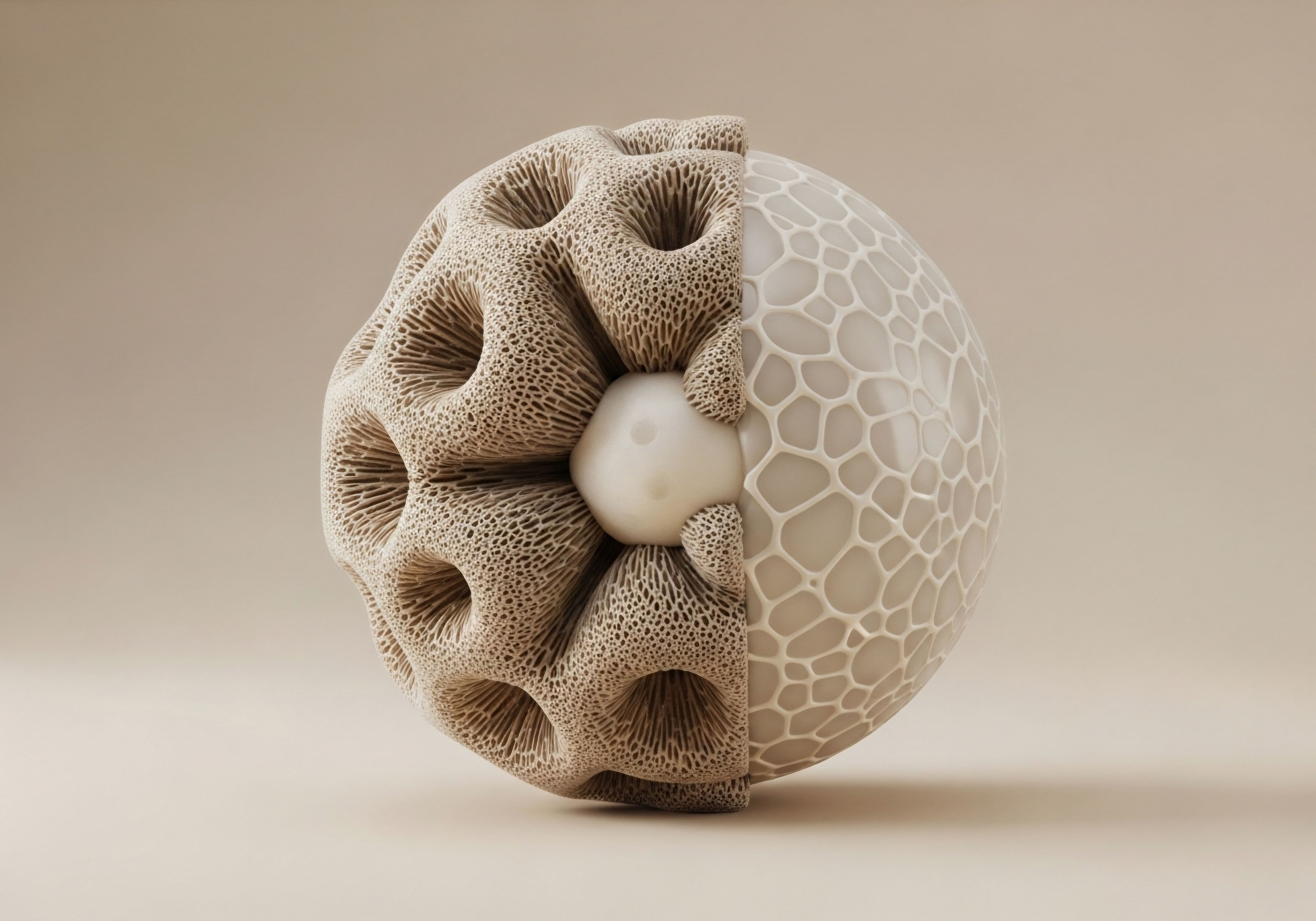

Academic

A granular analysis of alcohol-induced endocrinopathy reveals a cascade of insults at the molecular and cellular levels. The resulting hormonal dysregulation is a direct consequence of cytotoxic effects, metabolic derangements, and profound alterations in the central nervous system’s regulatory feedback loops. The question of irreversibility hinges on the distinction between functional suppression, which may be correctable, and permanent structural damage Meaning ∞ Structural damage refers to any physical alteration or disruption to the normal architecture, integrity, or composition of tissues, organs, or cellular components within the body. to glandular tissues and neural pathways.

Testicular Toxicity the Direct Cellular Insult

The primary mechanism behind alcohol-induced male hypogonadism is direct testicular toxicity. Ethanol and its primary metabolite, acetaldehyde, exert a potent cytotoxic effect on the testicular Leydig cells. This process is mediated through several pathways. Acetaldehyde can disrupt testosterone production Meaning ∞ Testosterone production refers to the biological synthesis of the primary male sex hormone, testosterone, predominantly in the Leydig cells of the testes in males and, to a lesser extent, in the ovaries and adrenal glands in females. by directly inhibiting key enzymes in the steroidogenic pathway.

Furthermore, the metabolism of alcohol within the testes generates a significant amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS). This state of oxidative stress leads to lipid peroxidation of cell membranes and damage to mitochondria, impairing the cellular machinery essential for testosterone synthesis. This direct cellular damage is a foundational element of the resulting hypogonadism and can, with sufficient chronicity, lead to testicular atrophy, a structural change that is far less amenable to reversal.

Hepatic Dysfunction and Aromatization

The liver’s role in hormone metabolism means that alcohol-induced liver damage, even at a subclinical level, compounds the hypogonadal state. The liver is a primary site for the expression of aromatase, the enzyme responsible for converting androgens (like testosterone) into estrogens. Chronic alcohol consumption upregulates aromatase activity.

In a state of alcoholic liver disease, this effect is magnified. Concurrently, a damaged liver is less efficient at clearing estrogens from circulation. This creates a potent biochemical scenario ∞ testosterone production is suppressed at the testicular level while the conversion of the remaining testosterone into estrogen is accelerated, leading to the clinical signs of hyperestrogenism and feminization seen in some men with chronic alcohol use disorder.

The irreversibility of hormonal damage is determined by the cumulative burden of cellular toxicity and the degree of structural change in endocrine tissues.

What Is the Neurological Basis for Hormonal Disruption?

Alcohol’s impact extends deep into the central nervous system, disrupting the very source of hormonal regulation. It interferes with hypothalamic function, suppressing the pulsatile release of LHRH, the master hormone that initiates the entire reproductive cascade. This appears to be mediated, in part, by alcohol’s effect on endogenous opioid systems.

Alcohol exposure increases the release of beta-endorphin in the hypothalamus, which has an inhibitory effect on LHRH secretion. Concurrently, alcohol disrupts the entire HPA axis, leading to a state of hypercortisolism. This chronic elevation of cortisol not only drives psychological and metabolic symptoms but also exerts its own suppressive effect on the HPG axis, further inhibiting reproductive function. This creates a vicious feedback loop where alcohol-induced stress physiology actively worsens gonadal function.

- Growth Hormone Suppression ∞ Alcohol consumption, particularly in the evening, has been shown to significantly blunt the nocturnal surge of Growth Hormone (GH) secretion from the pituitary gland. This disruption impairs the normal processes of tissue repair, cellular regeneration, and maintenance of lean body mass.

- Pituitary Signal Disruption ∞ Beyond LHRH, alcohol can directly impair the pituitary’s sensitivity and response to hypothalamic signals, affecting the release of both LH and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), which is crucial for spermatogenesis.

- Systemic Inflammation ∞ Alcohol-induced gut inflammation and liver damage contribute to a state of chronic systemic inflammation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines released into the circulation can cross the blood-brain barrier and further sensitize the HPA axis and suppress gonadal function, integrating the immune system into this complex web of hormonal failure.

The Potential for Permanent Alterations

While functional suppression of the HPG axis can show remarkable recovery with abstinence, the potential for irreversible damage lies in structural changes. Chronic exposure to ethanol’s neurotoxic effects can lead to neuronal loss in key areas of the brain, including the hypothalamus.

Similarly, long-term testicular toxicity Meaning ∞ Testicular toxicity refers to the impairment of normal testicular function, specifically affecting spermatogenesis, which is sperm production, and/or steroidogenesis, the synthesis of male hormones like testosterone. can result in a permanent reduction in the Leydig cell population. In these instances, even with the removal of alcohol, the body’s capacity to produce and regulate hormones may be permanently diminished. Therefore, a prognosis for recovery must consider not only the duration of abstinence but also an assessment of the underlying structural integrity of the endocrine glands and their neural control centers.

| Hormone | Observed Change | Primary Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Testosterone |

Decrease |

Direct cytotoxicity to Leydig cells; suppression of LH; increased aromatization to estrogen. |

| Estradiol (in males) |

Increase |

Increased aromatase activity in liver and adipose tissue; reduced hepatic clearance. |

| Cortisol |

Increase |

Chronic activation and dysregulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. |

| Growth Hormone (GH) |

Decrease |

Suppression of pituitary release, particularly the nocturnal surge during deep sleep. |

| Luteinizing Hormone (LH) |

Decrease |

Suppression of hypothalamic LHRH release and direct pituitary inhibition. |

References

- Ruiz, L. et al. “Alcohol-induced hypogonadism ∞ reversal after ethanol withdrawal.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, vol. 20, no. 3, 1987, pp. 255-60.

- Rachdaoui, N. and D. K. Sarkar. “Pathophysiology of the Effects of Alcohol Abuse on the Endocrine System.” Alcohol Research ∞ Current Reviews, vol. 38, no. 2, 2017, pp. 255-276.

- Emanuele, M. A. and N. V. Emanuele. “Alcohol’s effects on male reproduction.” Alcohol Health and Research World, vol. 25, no. 4, 2001, pp. 282-7.

- Prinz, P. N. et al. “Effect of alcohol on sleep and nighttime plasma growth hormone and cortisol concentrations.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 51, no. 4, 1980, pp. 759-64.

- Bannister, P. and S. Lowosky, M.S. “Alcohol and the Endocrine System.” Alcohol Health & Research World, vol. 11, no. 2, 1987, pp. 8-10, 27.

- Van Thiel, D. H. et al. “Alcohol-induced testicular atrophy. An experimental model for hypogonadism occurring in chronic alcoholic men.” Gastroenterology, vol. 69, no. 2, 1975, pp. 326-32.

- Purohit, V. “Can alcohol promote aromatization of androgens to estrogens? A review.” Alcohol, vol. 22, no. 3, 2000, pp. 123-7.

- Walter, M. F. et al. “Effects of abstinence on sex hormone profile in alcoholic patients without liver failure.” Revista Medica de Chile, vol. 125, no. 3, 1997, pp. 280-6.

- Badrick, E. et al. “The relationship between alcohol consumption and cortisol secretion in an aging cohort.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 93, no. 3, 2008, pp. 750-7.

- Cicero, T. J. “Alcohol’s Effects on Male Reproduction ∞ The Role of the Hypothalamus and Pituitary.” Alcohol Health & Research World, vol. 11, no. 2, 1987, pp. 16-17, 27.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a biological map of the damage that can occur. It validates the symptoms you feel and connects them to specific physiological processes. This knowledge is a powerful tool. It transforms a vague sense of being unwell into a defined set of biological challenges that can be addressed.

Your personal health narrative is unique, and the extent of hormonal disruption, as well as your capacity for recovery, is individual. This understanding is the starting point for a targeted, informed conversation with a clinical provider who can help translate this science into a personalized protocol for reclaiming your body’s equilibrium and function.