Fundamentals

You may feel a persistent, low-grade sense of being out of sync with the world. It can manifest as a weariness that sleep does not resolve, a subtle but stubborn weight gain around your midsection, or a mental fog that clouds your afternoons. This experience is a valid biological signal.

Your body operates on an internal, 24-hour schedule, a masterfully orchestrated series of rhythms that dictates nearly every aspect of your physiology. When this internal timing system becomes desynchronized from your daily life, the dissonance reverberates through your cells, leading to tangible symptoms. This is the starting point for understanding the deep connection between your internal world and your metabolic health.

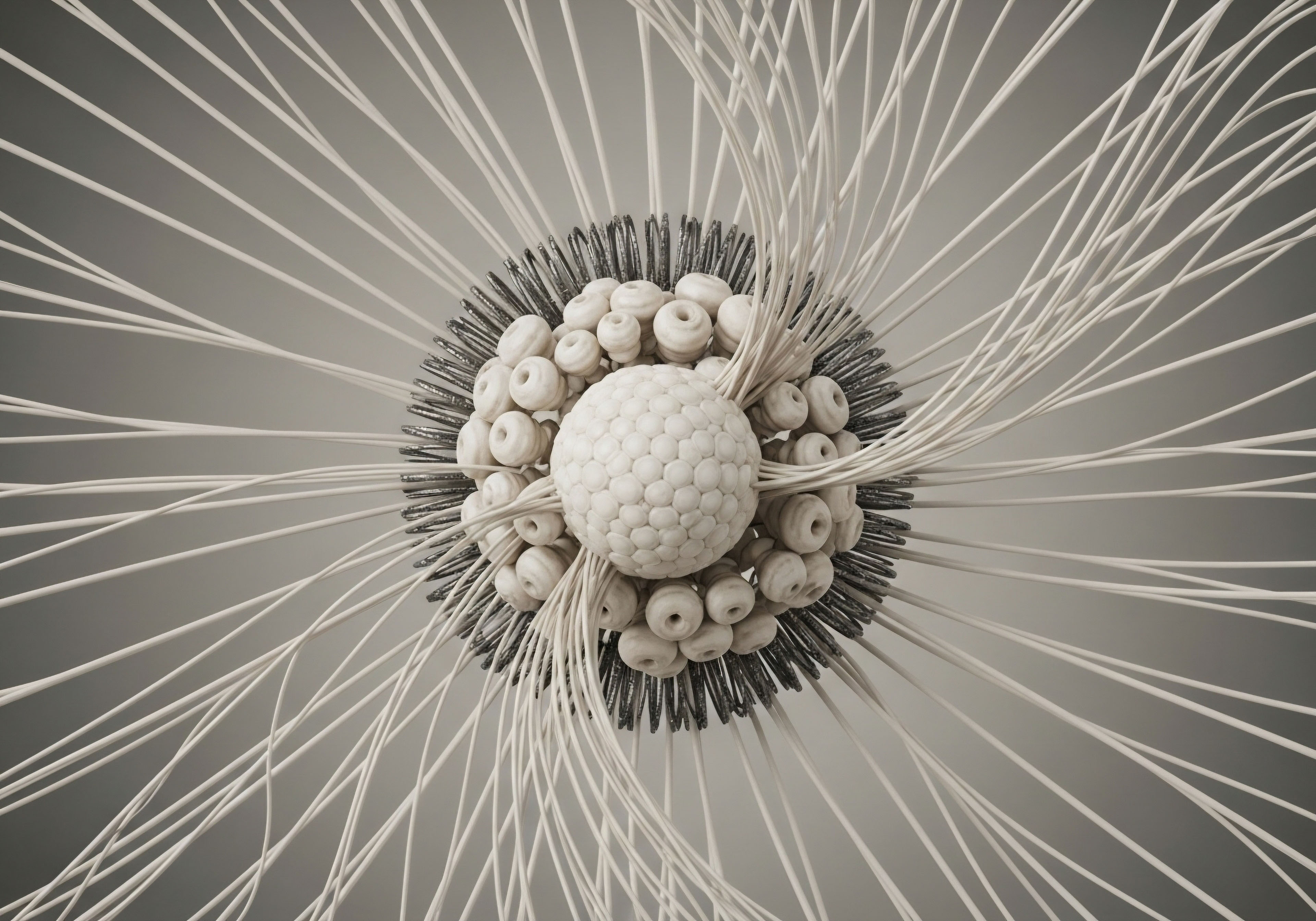

The human body contains a master clock Meaning ∞ The Master Clock, scientifically the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus, is the brain’s primary endogenous pacemaker. located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus Meaning ∞ The Suprachiasmatic Nucleus, often abbreviated as SCN, represents the primary endogenous pacemaker located within the hypothalamus of the brain, responsible for generating and regulating circadian rhythms in mammals. (SCN) of the hypothalamus. This central coordinator synchronizes countless smaller, peripheral clocks located in your organs, tissues, and even individual cells.

Think of the SCN as the conductor of a vast orchestra, ensuring that the violins of the liver, the percussion of the digestive system, and the woodwinds of the pancreas all play in perfect time. Light, particularly morning sunlight, is the primary cue that sets this master conductor’s tempo each day.

This elegant system evolved to align our internal processes ∞ like hormone release, digestion, and cellular repair ∞ with the external cycle of day and night. When this alignment is consistently disturbed by modern lifestyle factors such as erratic sleep schedules, late-night meals, and constant artificial light, the orchestra falls into disarray. Each section begins to play to its own beat, creating a state of internal temporal chaos.

What Is the Connection between Internal Clocks and Metabolism?

Metabolic syndrome is a collection of risk factors that indicate a breakdown in your body’s ability to manage energy. The presence of this syndrome signifies that multiple systems are under strain, increasing the likelihood of developing more serious conditions. The components are clinically specific and measurable.

- Abdominal Obesity ∞ An accumulation of visceral fat around the organs in the abdominal cavity, which is metabolically active and inflammatory.

- Elevated Triglycerides ∞ High levels of a type of fat found in the blood that the body uses for energy.

- Low High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL) Cholesterol ∞ A reduction in the “good” cholesterol that helps remove other forms of cholesterol from the bloodstream.

- High Blood Pressure ∞ The force of blood pushing against the walls of your arteries is consistently too high, straining the cardiovascular system.

- Elevated Fasting Blood Sugar ∞ An indication that the body is struggling to manage glucose effectively, often a precursor to insulin resistance.

Each of these indicators is profoundly influenced by your internal clocks. Your pancreas, for example, is programmed to be most sensitive to insulin during the day and less so at night. Eating a large meal late at night forces it to work inefficiently, contributing to elevated blood sugar and insulin resistance over time.

Similarly, your liver’s detoxification and fat-processing functions are scheduled for the overnight fasting period. Constant food intake, especially late in the evening, disrupts this vital maintenance cycle. The result of this chronic desynchronization is the slow, progressive emergence of the very symptoms that define metabolic syndrome. The fatigue you feel is your cellular energy systems struggling; the weight gain is your body’s response to mis-timed metabolic signals.

Chronic desynchronization of the body’s internal clocks is a foundational driver of metabolic dysfunction.

The Body’s Internal Messaging System

Hormones are the chemical messengers that carry instructions from the master clock to the peripheral tissues. Cortisol, the alertness hormone, is designed to peak in the morning to align with the start of the active period. Melatonin, the hormone of darkness, rises in the evening to prepare the body for sleep and repair.

This daily hormonal rhythm is a direct output of your circadian system. When you are exposed to bright light late at night or your sleep schedule is inconsistent, this finely tuned rhythm is flattened. Cortisol may remain high in the evening, promoting a state of stress and interfering with sleep. Melatonin production can be suppressed, robbing your cells of a powerful antioxidant and a key signal for rest.

This disruption extends to metabolic hormones as well. Leptin and ghrelin, which regulate hunger and satiety, also follow a circadian pattern. Sleep deprivation and circadian misalignment are known to decrease leptin (the satiety signal) and increase ghrelin (the hunger signal), leading to increased appetite and a preference for energy-dense foods.

This creates a physiological predisposition for weight gain. The entire endocrine system is built upon a foundation of timing. By understanding that your symptoms are a logical consequence of a systemic timing issue, you can begin to see a clear path toward restoration. The goal is to re-establish the predictable, rhythmic environment your biology expects, allowing your internal orchestra to play in harmony once more.

Intermediate

Recognizing the link between circadian disruption Meaning ∞ Circadian disruption signifies a desynchronization between an individual’s intrinsic biological clock and the external 24-hour light-dark cycle. and metabolic syndrome provides the diagnostic framework. Applying specific lifestyle interventions Meaning ∞ Lifestyle interventions involve structured modifications in daily habits to optimize physiological function and mitigate disease risk. offers the therapeutic tools for recalibration. These interventions are direct inputs into the body’s timekeeping machinery, designed to amplify the natural signals that synchronize the master clock in the brain with the peripheral clocks throughout the body.

The process involves a conscious structuring of your daily routines around the principles of light exposure, meal timing, physical activity, and sleep hygiene. Each pillar works synergistically to restore the coherent, predictable rhythms that underpin metabolic health.

The central principle is to create a high-amplitude, clear distinction between your active day-state and your restful night-state. Modern life often blurs this line, with dim indoor environments during the day and bright, stimulating screens at night.

This creates a weak, ambiguous signal for the SCN, causing it to lose its firm grip on the body’s peripheral clocks. The interventions described here are designed to sharpen that contrast, providing your biology with the unambiguous cues it needs to function optimally. This is a process of actively managing the environmental inputs that your genes have been programmed to expect for millennia.

Strategic Light Exposure

Light is the most potent synchronizing agent for the human circadian system. The timing, intensity, and color spectrum of light you are exposed to directly adjusts the master clock in your SCN. The goal is to maximize bright, blue-rich light during the day and minimize it in the hours leading up to sleep. This single practice can have a profound effect on hormonal cascades, neurotransmitter production, and overall metabolic regulation.

- Morning Light Anchor ∞ Upon waking, expose yourself to direct, natural sunlight for 10-30 minutes. This should be done as early as possible. The blue and UVA frequencies present in morning sunlight trigger a strong activation of the SCN, signaling the start of the biological day. This act anchors the entire 24-hour cycle, initiating a cascade that includes a healthy cortisol peak and the suppression of melatonin.

- Daytime Light Maximization ∞ Spend as much time as possible in brightly lit environments during the day. If you work indoors, position your desk near a window. Use bright, full-spectrum indoor lighting to supplement natural light. The objective is to signal to your body that it is unequivocally daytime, the period for alertness, activity, and energy expenditure.

- Evening Light Minimization ∞ In the 2-3 hours before your desired bedtime, dramatically reduce your exposure to light, especially from overhead sources and screens. The blue light emitted by electronic devices is particularly effective at suppressing melatonin production, delaying the onset of sleep and disrupting its quality. Use dim, warm-toned lamps, enable “night mode” on all devices, or consider using blue-light-blocking glasses as a practical tool.

This deliberate management of light is a form of biological communication. You are providing your brain with the clear, high-contrast information it needs to execute its timekeeping function correctly. This, in turn, ensures that the hormonal signals sent to your organs are timed appropriately for optimal function.

Deliberate management of light exposure is a primary tool for anchoring the body’s master clock.

How Does Meal Timing Influence Metabolic Health?

The timing of your food intake is a powerful synchronizing cue for the peripheral clocks Meaning ∞ Peripheral clocks are autonomous biological oscillators present in virtually every cell and tissue throughout the body, distinct from the brain’s central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. in your metabolic organs, particularly the liver, pancreas, and intestines. When you eat, you are telling these organs that it is the “active” phase.

A strategy known as time-restricted eating Meaning ∞ Time-Restricted Eating (TRE) limits daily food intake to a specific window, typically 4-12 hours, with remaining hours for fasting. (TRE) involves consolidating all of your caloric intake into a consistent window of 8-10 hours each day. This practice provides a daily period of extended fasting that allows these organs to switch from active processing to a state of repair and maintenance.

Consuming food late at night, when your pancreas is less insulin-sensitive and your digestive system is preparing for shutdown, is a form of metabolic jet lag. It forces your organs to perform tasks for which they are biologically unprepared, leading to inefficient glucose metabolism, fat storage, and increased inflammation.

By aligning your eating window with the active daylight hours, you synchronize your metabolic clocks with your master SCN clock. This alignment improves insulin sensitivity, promotes cellular clean-up processes (autophagy), and can help reverse the markers of metabolic syndrome, such as high triglycerides and elevated blood sugar.

| Time of Day | Action | Biological Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 6:30 AM – 7:00 AM | Wake up. Get 15 minutes of direct morning sunlight. | Anchors the SCN master clock, triggers cortisol release, and suppresses melatonin. |

| 8:00 AM | Light physical activity (e.g. walking). | Increases body temperature and further reinforces the start of the active period. |

| 10:00 AM | First meal of the day. | Initiates the digestive and metabolic processes during a period of high insulin sensitivity. |

| 1:00 PM | Second meal of the day. | Continues to fuel the body during the peak of the active phase. |

| 6:00 PM | Final meal of the day. | Provides energy before the overnight fast begins, timed to avoid late-night metabolic load. |

| 8:00 PM | Begin minimizing light exposure. Dim lights, wear blue-blocking glasses. | Allows for the natural rise of melatonin, signaling the brain to prepare for sleep. |

| 10:30 PM | Go to sleep in a cool, dark room. | Facilitates deep, restorative sleep, during which cellular repair and memory consolidation occur. |

The Role of Clinical Support

For some individuals, lifestyle interventions alone may not be sufficient to fully restore metabolic and hormonal balance, particularly when deficiencies have become chronic or are compounded by age-related changes. In these cases, targeted clinical protocols can serve as a powerful adjunct. For example, testosterone exhibits a distinct circadian rhythm, peaking in the morning.

In men with clinically low testosterone, restoring this rhythm with Testosterone Replacement Therapy Meaning ∞ Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) is a medical treatment for individuals with clinical hypogonadism. (TRT) can have systemic benefits that support the broader goal of circadian restoration. The protocol, often involving weekly injections of Testosterone Cypionate combined with agents like Gonadorelin to maintain testicular function, aims to re-establish a physiological hormonal environment. This can improve energy levels, body composition, and insulin sensitivity, making it easier to engage in the very lifestyle practices ∞ like exercise ∞ that further support circadian health.

Similarly, for women experiencing hormonal fluctuations during perimenopause or post-menopause, low-dose testosterone therapy or progesterone support can help stabilize the endocrine system. These interventions are designed to address specific deficits within the system, providing a level of stability that allows the foundational lifestyle changes to be more effective.

Peptide therapies, such as Sermorelin or Ipamorelin, which stimulate the body’s own production of growth hormone, also align with circadian principles. Growth hormone is released in pulses, primarily during deep sleep. Using these peptides can help restore this natural rhythm, improving sleep quality, body composition, and recovery, all of which are intertwined with metabolic function.

Academic

A detailed examination of metabolic syndrome Meaning ∞ Metabolic Syndrome represents a constellation of interconnected physiological abnormalities that collectively elevate an individual’s propensity for developing cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. through the lens of molecular chronobiology reveals a deeply intertwined relationship between the cellular clock machinery and metabolic homeostasis. The reversal of early metabolic syndrome indicators via lifestyle interventions is predicated on the plasticity of the epigenome and the restoration of transcriptional-translational feedback loops within the core clock mechanism.

The central and peripheral clocks are not merely passive timekeepers; they are active participants in metabolic regulation, directly controlling the expression of genes involved in glucose transport, lipid metabolism, and insulin signaling. Circadian disruption, therefore, is a primary pathogenic mechanism, inducing a state of systemic and tissue-specific desynchrony that drives the metabolic phenotype.

The core molecular clock within each cell is composed of a set of clock genes. The primary loop involves the heterodimerization of two transcription factors, CLOCK (Circadian Locomotor Output Cycles Kaput) and BMAL1 Meaning ∞ BMAL1, or Brain and Muscle ARNT-Like 1, identifies a foundational transcription factor integral to the mammalian circadian clock system. (Brain and Muscle Arnt-Like 1).

This complex binds to E-box elements in the promoter regions of the Period (PER1, PER2, PER3) and Cryptochrome (CRY1, CRY2) genes, activating their transcription. The resulting PER and CRY proteins then accumulate in the cytoplasm, dimerize, and translocate back into the nucleus to inhibit the activity of the CLOCK-BMAL1 complex, thus repressing their own transcription.

This negative feedback loop Meaning ∞ A negative feedback loop represents a core physiological regulatory mechanism where the output of a system works to diminish or halt the initial stimulus, thereby maintaining stability and balance within biological processes. takes approximately 24 hours to complete, forming the fundamental oscillation of the cellular clock. A secondary loop involving the nuclear receptors REV-ERBα/β and RORα/β adds stability and robustness to this rhythm by regulating the transcription of BMAL1 itself. It is the integrity of these interlocking loops that governs the rhythmic expression of thousands of downstream clock-controlled genes (CCGs) that execute tissue-specific metabolic functions.

Can Restoring Clock Gene Expression Reverse Cellular Damage?

Lifestyle interventions such as time-restricted eating and scheduled light exposure Meaning ∞ Light exposure defines the intensity and duration of ambient light reaching an individual’s eyes. function as potent “zeitgebers” (time givers) that entrain these molecular loops. For instance, the timing of food intake directly influences the clock in the liver. In a fed state, insulin signaling pathways are activated, which can modulate the phosphorylation and stability of clock proteins.

Conversely, during a fasted state, the activation of AMPK and SIRT1 ∞ two key energy sensors ∞ directly impacts the clock machinery. SIRT1, a NAD+-dependent deacetylase, can deacetylate and activate BMAL1, physically linking the cell’s energy status to its timekeeping mechanism.

Therefore, a consistent daily fasting period, as achieved through TRE, restores the high-amplitude oscillation of these pathways in the liver. This leads to the correctly timed expression of genes involved in gluconeogenesis and lipogenesis, preventing the ectopic fat deposition and impaired glucose tolerance characteristic of metabolic syndrome.

Experimental models have demonstrated this principle with precision. Mice subjected to a high-fat diet but restricted to an 8-hour feeding window are protected from obesity, hyperinsulinemia, and hepatic steatosis compared to mice allowed to eat the same diet ad libitum. This protection occurs despite identical caloric intake, highlighting the profound impact of temporal regulation.

The intervention effectively re-synchronizes the hepatic clock, restoring the rhythmic expression of metabolic genes. This suggests that the pathogenic effects of a “bad” diet can be substantially mitigated by enforcing a “good” clock. The reversal of early indicators is thus a direct consequence of restoring the transcriptional fidelity of the metabolic genome, which had been compromised by temporal disruption.

The integrity of molecular clock gene feedback loops is directly linked to the cell’s metabolic programming and function.

Epigenetic Modifications and Hormonal Crosstalk

Chronic circadian disruption, such as that experienced by long-term shift workers, can lead to more durable changes in metabolic function through epigenetic modifications. Studies have identified altered DNA methylation patterns in the promoter regions of key clock genes Meaning ∞ Clock genes are a family of genes generating and maintaining circadian rhythms, the approximately 24-hour cycles governing most physiological and behavioral processes. like CLOCK and PER2 in individuals with type 2 diabetes.

This represents a form of cellular memory, where the system becomes locked in a state of dysrhythmia. Lifestyle interventions may work in part by remodeling the epigenome. For example, exercise is known to influence DNA methylation and histone acetylation. When timed correctly (e.g. during the active phase), it could potentially reverse some of these maladaptive epigenetic marks, restoring the responsiveness of clock genes to their entrainment signals.

The interaction with the endocrine system adds another layer of complexity. Glucocorticoids, like cortisol, are a primary hormonal output of the SCN and a powerful synchronizing signal for peripheral clocks. The cortisol receptor is a transcription factor that can directly bind to glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) in the promoters of clock genes, including PER2.

A flattened cortisol rhythm Meaning ∞ The cortisol rhythm describes the predictable daily fluctuation of the body’s primary stress hormone, cortisol, following a distinct circadian pattern. ∞ a hallmark of chronic stress and circadian disruption ∞ provides a weak and noisy signal to peripheral tissues, contributing to their desynchronization. Restoring a robust morning cortisol peak through anchored light exposure and consistent sleep is therefore a critical step in re-establishing systemic temporal order.

This is where clinical interventions can intersect with lifestyle. The administration of TRT, for instance, does not just elevate testosterone levels; it can also influence the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and, by extension, the cortisol rhythm, providing an additional lever to support systemic resynchronization.

| Gene | Primary Function in Core Clock | Result of Genetic or Functional Disruption |

|---|---|---|

| BMAL1 | Forms the primary transcriptional activator complex with CLOCK. A positive limb of the feedback loop. | Ablation leads to complete loss of circadian rhythmicity. Associated with hyperglycemia, hypoinsulinemia, and adiposity. |

| CLOCK | Partners with BMAL1 to activate transcription of PER and CRY genes. Possesses histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity. | Mutation can lead to a lengthened circadian period. Associated with obesity, hyperlipidemia, and hepatic steatosis. |

| PER2 | A core component of the negative feedback loop. Inhibits CLOCK-BMAL1 activity. | Disruption leads to a shortened period and is linked to impaired glucose homeostasis and a predisposition to a diabetes-like state. |

| CRY1 | The primary transcriptional repressor in the negative feedback loop. A potent inhibitor of CLOCK-BMAL1. | Deletion can cause elevated blood glucose and insulin resistance, particularly under a high-fat diet. |

| REV-ERBα | A nuclear receptor that rhythmically represses BMAL1 transcription, forming the stabilizing loop. | Disruption alters lipid and glucose metabolism. It is a direct link between the clock and metabolic pathways like lipogenesis. |

The evidence strongly supports the hypothesis that lifestyle interventions targeting circadian rhythm Meaning ∞ The circadian rhythm represents an endogenous, approximately 24-hour oscillation in biological processes, serving as a fundamental temporal organizer for human physiology and behavior. can reverse the early indicators of metabolic syndrome. This reversal is achieved by restoring the integrity of the molecular clockwork at both a systemic and cellular level. The process involves re-establishing high-amplitude environmental zeitgebers, which in turn entrain the central and peripheral clocks, correct epigenetic drift, and restore the fidelity of rhythmic gene expression that governs metabolic health.

References

- Panda, Satchin. “Circadian disruption, clock genes, and metabolic health.” Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 134, no. 14, 2024.

- Karatsoreos, Ilia N. “The relationship between circadian disruption and the development of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.” Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity ∞ Targets and Therapy, vol. 7, 2014, pp. 523-533.

- Zimmet, Paul, et al. “The Circadian Syndrome ∞ is the Metabolic Syndrome and much more!” Journal of Internal Medicine, vol. 286, no. 2, 2019, pp. 181-191.

- Maury, Eleonore, et al. “Circadian Rhythms and Metabolic Syndrome.” Circulation Research, vol. 106, no. 3, 2010, pp. 447-462.

- Turek, Fred W. et al. “Obesity and the circadian clock.” Science, vol. 308, no. 5724, 2005, pp. 1043-1045.

- Scheer, Frank A. J. L. et al. “Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 106, no. 11, 2009, pp. 4453-4458.

- Wehrens, Sophie M. T. et al. “Meal Timing and Type 2 Diabetes Risk ∞ A Review of the Evidence.” Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 12, 2021, p. 4496.

- Guyton, Arthur C. and John E. Hall. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 13th ed. Elsevier, 2016.

- Boron, Walter F. and Emile L. Boulpaep. Medical Physiology. 3rd ed. Elsevier, 2017.

- “Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, Third Edition.” American Psychiatric Association, 2010.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a biological blueprint, a map connecting the subtle feelings of being unwell to the precise, microscopic gears of your internal clocks. This knowledge transforms the conversation from one of managing symptoms to one of restoring systems. It places the power of regulation back into the rhythm of your daily life.

The path forward begins with observing your own patterns, recognizing the points of friction between your lifestyle and your innate biological schedule. What part of this intricate system is calling for your attention first?

A Journey of Self-Calibration

Each day offers a new opportunity to send a clearer signal to your body. Each meal, each exposure to morning light, and each hour of restful sleep is an act of communication with your own physiology. This is a personal process of recalibration.

The ultimate goal is to create a life where the demands of your environment and the needs of your biology move in a synchronized, supportive dance. The journey is one of self-awareness, grounded in the profound understanding that your body is always striving for balance. Your role is to provide it with the fundamental conditions it requires to succeed.