Fundamentals

Your journey into hormonal optimization is a deeply personal one, often beginning with a collection of symptoms that feel disconnected. You might be addressing menopausal symptoms with oral estrogens, a standard and effective protocol, yet simultaneously experiencing a persistent, creeping fatigue, a sensitivity to cold, or a mental fog that clouds your day.

It is a common experience to solve one set of issues only to feel that another has appeared. Your body’s endocrine system is an intricate, interconnected web of communication. Introducing an external signal, such as oral estrogen, creates a series of biochemical responses throughout that system. The link between your estrogen therapy and your thyroid function is a prime example of this systemic conversation.

When you ingest an oral estrogen tablet, it first travels to your liver before entering general circulation. This “first-pass metabolism” is a standard physiological process. Inside the liver, estrogen molecules send a powerful signal to the cells, instructing them to increase the production of various proteins.

One specific protein, thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG), is of particular interest. Think of TBG as a dedicated taxi service for your thyroid hormones. Its job is to bind to thyroxine (T4), the primary hormone produced by your thyroid gland, and transport it safely through the bloodstream. This binding process is normal and necessary.

Oral estrogen therapy prompts the liver to produce more of the protein that binds to thyroid hormone, which can reduce the amount of active hormone available to your cells.

The administration of oral estrogens leads to a significant increase in the number of these TBG taxis on the road. Consequently, more of your circulating T4 gets picked up and bound into these vehicles.

While the total amount of thyroid hormone in your blood might remain the same or even increase, the amount of “free” or “bioavailable” hormone ∞ the T4 that can actually get out of the taxi and enter your cells to do its job ∞ decreases.

Your cells, from your brain to your muscles, only recognize and use this free hormone. When its availability drops, you begin to feel the classic symptoms of an underactive thyroid system, even if your thyroid gland itself is perfectly healthy. This is the biological root of the disconnect you may be feeling, and understanding this mechanism is the first step toward addressing it systemically.

The Thyroid Axis and Cellular Energy

Your thyroid gland does not operate in isolation. It is part of a sophisticated feedback loop known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis. The hypothalamus in your brain signals the pituitary gland, which in turn releases Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) to tell the thyroid how much hormone to produce.

This system is exquisitely sensitive to the levels of free thyroid hormone in the blood. When it senses a drop in free T4, the pituitary releases more TSH, asking the thyroid to work harder. In the context of elevated TBG from oral estrogens, your TSH may rise as the body attempts to compensate for the reduced bioavailability of its active hormones.

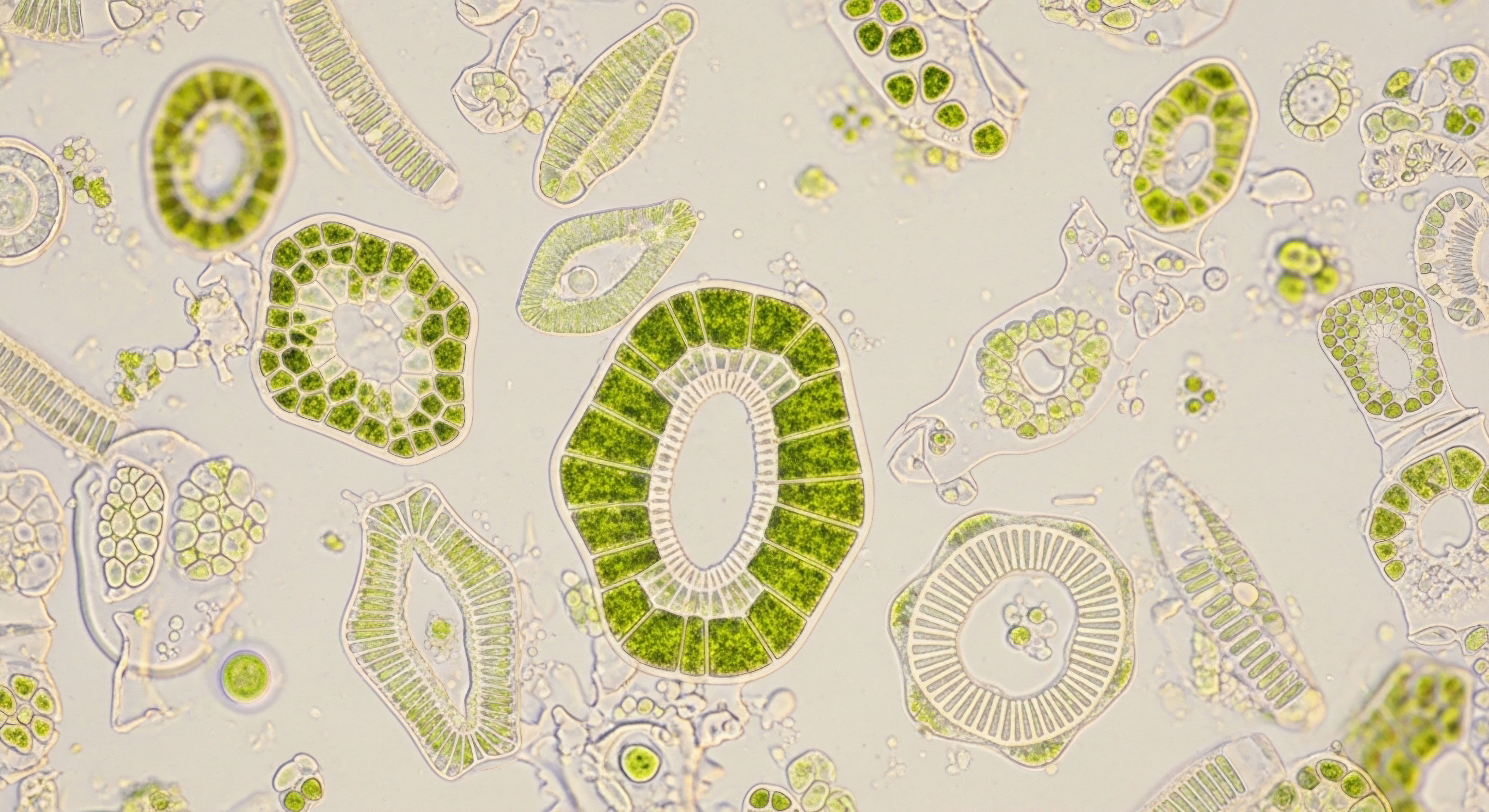

The ultimate destination for thyroid hormone is the mitochondria within your cells, the tiny power plants responsible for generating ATP, the body’s primary energy currency. Free T4 travels to the cells, where it is converted into its more potent, active form, triiodothyronine (T3).

This T3 then enters the cell nucleus and mitochondria, directly regulating the rate of your metabolism. When less free hormone is available, this entire process slows down. Your metabolic rate drops, leading to symptoms like fatigue, weight gain, and cold intolerance. Supporting this intricate system involves ensuring the thyroid has the raw materials it needs to produce hormones and that the body can efficiently convert T4 to T3, a process that becomes even more important when bioavailability is challenged.

Intermediate

Understanding that oral estrogens impact thyroid hormone availability via increased hepatic TBG production allows for a more targeted approach to wellness. This is a predictable pharmacological effect, a known variable that can be accounted for. The goal of lifestyle interventions is to build systemic resilience, optimizing every other step of the thyroid hormone pathway to compensate for the specific challenge introduced by increased binding.

This involves a multi-pronged strategy focused on nutrient sufficiency for hormone synthesis and conversion, supporting detoxification pathways that affect hormonal balance, and managing systemic stressors that can further impair thyroid function.

The primary objective is to support the body’s ability to maintain adequate levels of free T3, the most biologically active thyroid hormone. The conversion of T4 to T3 is a selenium-dependent enzymatic process that occurs primarily in the liver and other peripheral tissues.

When TBG levels are high, efficiently converting the available free T4 into active T3 becomes a higher priority. Lifestyle and dietary choices can directly supply the essential cofactors for these enzymatic processes, ensuring the machinery of thyroid hormone metabolism runs as smoothly as possible.

Nutritional Protocols for Thyroid Support

A diet designed to support thyroid function while on oral estrogens provides the building blocks for hormone production and the cofactors for their activation. It is a therapeutic application of nutrition aimed at a specific biochemical outcome.

Key Nutrient Cofactors

Certain minerals and vitamins are indispensable for the thyroid hormone life cycle. Ensuring adequate intake through diet is the foundational step in supporting the system.

- Selenium ∞ This mineral is a critical component of the deiodinase enzymes that convert T4 to T3. Without sufficient selenium, this conversion is inefficient, leading to lower levels of active thyroid hormone. Dietary sources are paramount.

- Zinc ∞ Zinc plays a role in the synthesis of thyroid hormones and the function of the TSH-releasing hormone in the hypothalamus. It is another key piece of the enzymatic machinery required for a healthy thyroid axis.

- Iodine ∞ The thyroid gland requires iodine to synthesize both T4 and T3. While deficiency is a well-known cause of hypothyroidism, excessive intake can also suppress thyroid function. A balanced intake from whole food sources is generally recommended over high-dose supplementation without clinical guidance.

- Iron ∞ The enzyme thyroid peroxidase, which is essential for producing thyroid hormone, is dependent on iron. Low iron levels can impair thyroid hormone production, compounding the issue of reduced bioavailability from high TBG.

What Is the Role of Gut Health in Hormone Regulation?

The gut microbiome plays a surprisingly significant role in hormonal balance. A healthy gut lining is essential for absorbing the very nutrients, like selenium and zinc, that are required for thyroid function. Furthermore, an emerging area of science is examining the “estrobolome,” a collection of gut bacteria that produce enzymes to metabolize estrogens.

An imbalance in the gut microbiome, or dysbiosis, can impair estrogen detoxification. This may lead to higher circulating levels of estrogen metabolites, further influencing liver function and systemic inflammation. A diet rich in fiber from diverse plant sources promotes a healthy microbiome, supporting both nutrient absorption and proper estrogen metabolism.

Strategic nutritional interventions can directly supply the cofactors needed for efficient thyroid hormone conversion, helping to offset the binding effects of proteins increased by oral estrogens.

Stress Modulation and Endocrine Function

Chronic stress, whether physiological or psychological, has a direct impact on the endocrine system. The activation of the body’s stress response system, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, results in the release of cortisol. Elevated cortisol can suppress the conversion of T4 to the active T3, favoring the production of reverse T3 (rT3), an inactive form of the hormone.

In a state where free T4 is already less available due to high TBG, further impairment of its conversion to T3 can significantly worsen hypothyroid symptoms. Practices that modulate the stress response are therefore a direct intervention for thyroid health.

Regular physical activity is a potent tool for managing stress and supporting metabolic health. It improves insulin sensitivity, which is closely linked to thyroid function, and helps regulate cortisol levels. Similarly, dedicated stress management practices like meditation, deep breathing exercises, or yoga have been shown to lower markers of chronic stress, thereby supporting a more favorable hormonal environment for T3 conversion.

| Nutrient | Primary Role | Rich Dietary Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Selenium | Cofactor for T4 to T3 conversion | Brazil nuts, seafood (tuna, sardines), poultry, eggs |

| Zinc | Thyroid hormone synthesis and TSH regulation | Oysters, red meat, poultry, pumpkin seeds, lentils |

| Iodine | Essential component of T4 and T3 hormones | Seaweed (kelp, nori), fish, dairy products, iodized salt |

| Iron | Cofactor for thyroid peroxidase enzyme | Lean meats, spinach, lentils, fortified cereals |

Academic

A molecular-level examination of the interaction between oral estrogens and the thyroid axis reveals a highly specific, predictable perturbation of endocrine homeostasis. The central mechanism is the estrogen-mediated upregulation of TBG gene expression in hepatocytes.

Oral administration subjects the liver to a high concentration of estrogen during first-pass metabolism, a pharmacological reality that is distinct from the physiology of endogenous hormones or transdermally delivered therapies. This bolus of estrogen interacts with estrogen receptors in the liver, initiating a signaling cascade that results in increased transcription and translation of the TBG protein. The clinical consequence, as documented in multiple studies, is a dose-dependent increase in serum TBG concentrations.

This elevation in binding proteins shifts the equilibrium between bound and free thyroid hormones. While total T4 (TT4) levels often rise, this is a reflection of the expanded protein-bound reservoir and is biochemically misleading. The physiologically relevant metric, free T4 (fT4), tends to decrease or fall to the low end of the normal range.

The pituitary gland, sensing this subtle drop in available fT4, responds by increasing TSH secretion in an attempt to restore homeostasis. For a euthyroid woman, this compensatory mechanism may be sufficient to maintain clinical euthyroidism, though often at the cost of a higher TSH. For a woman with pre-existing hypothyroidism on levothyroxine therapy, this shift is often clinically significant, increasing her exogenous T4 requirement by as much as 25-50%.

The Superiority of Transdermal Administration

The most direct lifestyle or protocol adjustment to mitigate this entire cascade is to alter the route of estrogen administration. Transdermal delivery of estradiol, via patches or gels, allows the hormone to enter the systemic circulation directly, bypassing the hepatic first-pass effect.

As a result, the liver is not exposed to the same supraphysiological concentrations of estrogen, and the stimulus for increased TBG production is largely avoided. Clinical studies consistently demonstrate that transdermal estradiol does not significantly alter serum TBG levels or TSH concentrations in both euthyroid and hypothyroid women.

This makes transdermal administration the preferred route for women with known thyroid disorders or for those who develop thyroid-related symptoms while on oral estrogens. It is a clear example of how altering the delivery method of a therapeutic agent can prevent a negative systemic interaction.

How Do Nutrient Deficiencies Impact Hormone Conversion?

The enzymatic conversion of T4 to T3 is the primary point of regulation for thyroid hormone activity and a key target for supportive interventions. This process is catalyzed by a family of selenoenzymes called deiodinases.

Type 1 deiodinase (D1), found mainly in the liver and kidneys, and Type 2 deiodinase (D2), found in the brain, pituitary, and brown adipose tissue, are responsible for generating the body’s supply of T3. The absolute requirement of selenium for the function of these enzymes cannot be overstated.

In a state of selenium deficiency, deiodinase activity is impaired, leading to a reduced T4-to-T3 conversion ratio. This is compounded by the fact that estrogen itself may influence selenium distribution and metabolism. Therefore, ensuring selenium sufficiency is a non-negotiable aspect of supporting a patient on oral estrogen therapy.

Bypassing the liver’s first-pass metabolism via transdermal estrogen delivery is a key clinical strategy to prevent the increase in thyroid-binding globulin and its downstream effects.

| Parameter | Oral Estrogen Administration | Transdermal Estrogen Administration |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatic First-Pass Metabolism | Yes, significant exposure of the liver | No, bypasses the liver initially |

| Serum TBG Levels | Significantly increased | No significant change |

| Total T4 (TT4) | Increased | No significant change |

| Free T4 (fT4) | May decrease or remain low-normal | No significant change |

| TSH | May increase to compensate | No significant change |

| Levothyroxine Dose Adjustment | Often required for hypothyroid patients | Generally not required |

Systemic Inflammation and Thyroid Resistance

A final layer of complexity involves the role of systemic inflammation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, which can be elevated due to a variety of lifestyle factors including poor diet, chronic stress, and gut dysbiosis, can have a suppressive effect on the thyroid axis.

They can downregulate deiodinase activity, reducing T3 production, and can also lead to a state of “thyroid resistance,” where cellular receptors become less sensitive to thyroid hormone. Oral estrogens can also have pro-inflammatory effects in some individuals.

An anti-inflammatory diet, rich in omega-3 fatty acids, polyphenols from colorful plants, and fiber, combined with regular exercise and stress management, works to lower this background level of systemic inflammation. This creates a more favorable physiological environment, enhancing the body’s ability to utilize the thyroid hormone that is available.

- Assess the Route of Administration ∞ The most impactful intervention is discussing the potential switch from oral to transdermal estrogen with a healthcare provider to avoid the primary insult to the thyroid axis.

- Optimize Nutritional Cofactors ∞ A targeted dietary approach focusing on selenium, zinc, and iron from whole foods is essential to support the enzymatic pathways of hormone synthesis and activation.

- Manage Systemic Inflammation and Stress ∞ An anti-inflammatory diet, consistent exercise, and dedicated stress reduction practices are foundational for reducing cortisol and cytokine levels that can interfere with thyroid hormone conversion and sensitivity.

References

- Mazer, N. A. “Interaction of estrogen therapy and thyroid hormone replacement in postmenopausal women.” Thyroid, vol. 14, no. 1, 2004, pp. 1S-10S.

- Raps, M. et al. “Effects of oral versus transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone on thyroid hormones, hepatic proteins, lipids, and quality of life in menopausal women with hypothyroidism ∞ a clinical trial.” Menopause, vol. 28, no. 9, 2021, pp. 1044-1052.

- Ben-Rafael, Z. et al. “Thyroid profile modifications during oral hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women.” Gynecological Endocrinology, vol. 9, no. 2, 1995, pp. 125-129.

- “Does oral contraceptive (OC) use increase thyroid-binding globulin (TBG) levels?” Google DeepMind, 21 Feb. 2025.

- “Can Thyroid Medication Affect Your Estrogen? A Deep Dive into Hormonal Interactions.” Marek Health, 21 Apr. 2023.

- “Lifestyle Changes to Support Thyroid Health.” Patiala Heart Institute, 20 Feb. 2024.

- “Diets and supplements for thyroid disorders.” British Thyroid Foundation, 7 Dec. 2024.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Internal Orchestra

The information presented here offers a map of the intricate biochemical pathways that connect your clinical therapies to your lived experiences. Understanding the mechanics of how oral estrogens interact with your thyroid system moves you from a passive recipient of care to an active, informed participant in your own health journey.

The human body is a complex, self-regulating system, and every intervention creates a ripple effect. The goal is to understand these ripples and use intelligent, targeted lifestyle strategies to guide them, ensuring all sections of your internal orchestra are playing in concert.

This knowledge is the foundation. It empowers you to ask more precise questions during clinical consultations and to recognize the subtle signals your body is sending. Your unique physiology, genetics, and lifestyle will determine your specific needs.

The path forward involves a partnership ∞ one between you, your body’s innate intelligence, and a clinical team that respects and understands this systemic approach to wellness. The ultimate aim is to achieve a state of calibrated health, where your internal systems are so well-supported that they can adapt and function optimally, allowing you to feel fully vital and present in your life.