Fundamentals

You may recognize the feeling intimately ∞ a profound fatigue that greets you upon waking, a sense of running on empty before the day has even begun. Perhaps you experience a paradoxical surge of energy late in the evening, your mind racing just as you should be winding down.

This experience, often described as feeling “wired and tired,” is a tangible sign of a system in disharmony. Your body is communicating a vital message through the language of its internal chemistry. At the heart of this conversation is cortisol, a steroid hormone that functions as your body’s primary internal messenger for alertness and energy management.

Its rhythm is designed to be a predictable, supportive wave, carrying you through the demands of the day and gently receding to allow for rest and repair at night.

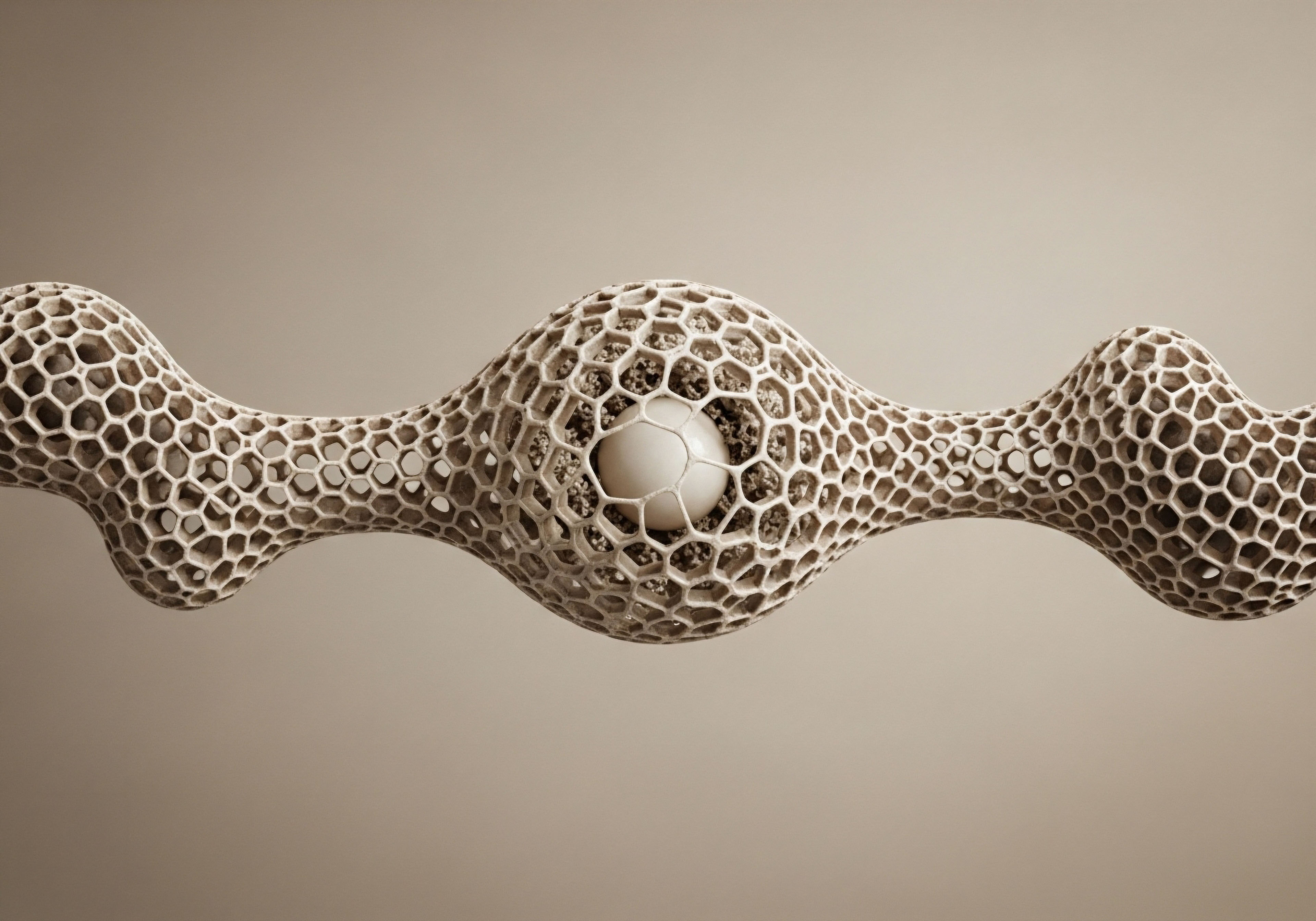

The cortisol pattern is governed by a sophisticated command center known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. Think of this as the central operating system for your stress response and energy regulation. The hypothalamus, a small region at the base of your brain, perceives the body’s needs ∞ including the cycle of day and night ∞ and sends signals to the pituitary gland.

The pituitary, in turn, messages the adrenal glands, which sit atop your kidneys, instructing them on how much cortisol to release. In a balanced state, this system produces a distinct rhythm. Cortisol levels should be highest in the morning, about 30 minutes after you wake up, in a surge called the Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR). This peak provides the momentum to start your day. From there, levels should gradually decline, reaching their lowest point around midnight to facilitate deep, restorative sleep.

When this elegant rhythm is disrupted, the consequences ripple through your entire physiology. A blunted morning cortisol peak can lead to that feeling of deep inertia and difficulty getting started. Elevated evening cortisol can manifest as anxiety, racing thoughts, and an inability to fall or stay asleep.

These are not mere feelings; they are physiological realities rooted in a dysregulated HPA axis. The question then becomes, are we passive victims of this internal clock, or can we actively engage with it? The answer is a resounding yes. Your daily lifestyle choices are powerful inputs that directly communicate with your HPA axis, allowing you to consciously and methodically recalibrate your cortisol rhythm and reclaim your vitality.

The Four Pillars of Cortisol Recalibration

Understanding the HPA axis provides the ‘why’; the four pillars of lifestyle intervention provide the ‘how’. These pillars are not isolated tactics but an integrated protocol for restoring hormonal conversation within your body. They are light exposure, nutrient timing, physical movement, and stress modulation. Each one acts as a potent signal that helps to re-entrain the natural rise and fall of cortisol, anchoring your internal clock to the external world and your body’s intrinsic needs.

Light the Primary Pacemaker

Light is arguably the most powerful external cue for regulating your circadian biology. Your brain’s master clock, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), is directly wired to receive information from your eyes. The timing, intensity, and color spectrum of light you are exposed to tells your SCN what time it is, which then directs the HPA axis to adjust cortisol output accordingly.

Getting bright, natural light exposure early in the morning reinforces a strong cortisol spike, essentially signaling the start of the physiological day. Conversely, exposure to bright, blue-spectrum light from screens and overhead lighting in the evening can suppress melatonin production and keep cortisol levels artificially elevated, disrupting the natural decline needed for sleep.

Nutrient Timing the Metabolic Clock

What you eat is important, and when you eat can be just as influential on your hormonal health. The practice of aligning your meals with your circadian rhythm is known as chrononutrition. Your metabolic machinery, including insulin sensitivity and digestive function, is not static; it fluctuates throughout the day, following the lead of your central clock.

Eating a substantial meal in the morning when your body is primed for metabolic activity supports healthy cortisol patterns. A large, late-night meal, however, can send a confusing signal to your system, forcing metabolic activity when your body is preparing for shutdown and potentially altering the overnight cortisol dip and subsequent morning rise.

Skipping breakfast is another pattern that can disrupt the HPA axis, as it may be interpreted by the body as a low-grade stressor, altering the expected morning cortisol peak.

Movement the Dynamic Modulator

Physical activity is a form of physiological stress, and as such, it elicits a cortisol response. The context and timing of this response determine whether it is beneficial or detrimental to your diurnal rhythm. Exercise, particularly moderate-intensity movement, in the morning can amplify the natural cortisol peak, enhancing alertness and reinforcing a robust daily cycle.

In contrast, high-intensity exercise performed late in the evening can spike cortisol at a time when it should be declining, potentially interfering with sleep onset and quality. The goal is to use exercise strategically, applying it as a stimulus that complements your body’s inherent rhythm, providing energy when needed and allowing for calm when required.

Stress Modulation the HPA Soother

The HPA axis is the literal stress response system. While acute stressors are a normal part of life, chronic, unmanaged stress leads to a constant state of HPA activation and elevated cortisol. This sustained output is what flattens the healthy, dynamic wave of cortisol into a dysfunctional, shallow line.

Practices such as mindfulness, meditation, deep breathing exercises, and even guided imagery have been shown to directly engage the parasympathetic nervous system, which is the “rest and digest” counterpart to the “fight or flight” system. Activating this calming branch of your nervous system sends a powerful signal to the hypothalamus to down-regulate the stress response, helping to lower chronically elevated cortisol and restore the sensitive feedback loops that govern its rhythm.

Intermediate

A flattened or erratic cortisol curve is a physiological state reflecting a breakdown in communication between your brain’s central clock and your adrenal glands. Restoring this dialogue requires a more granular understanding of the mechanisms at play. Lifestyle interventions succeed when they are applied with precision, targeting the specific biological pathways that govern the HPA axis.

This moves beyond general advice into a personalized protocol designed to re-establish a healthy, functional rhythm, which is foundational to overall well-being and the efficacy of other clinical protocols, such as hormonal optimization therapies.

Strategic interventions in light, nutrition, and exercise can directly influence the molecular machinery of the body’s timekeeping systems.

Calibrating the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus with Light

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus functions as the body’s master pacemaker. It interprets light signals received from specialized cells in your retina called intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs). These cells are particularly sensitive to blue-wavelength light.

When you expose your eyes to bright, blue-rich light in the morning, the ipRGCs send a strong “wake up” signal to the SCN. The SCN then relays this message down through the HPA axis, promoting a robust release of cortisol from the adrenal glands. This is the mechanism that underpins the Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR), a critical marker of a healthy diurnal rhythm.

A study published in the journal Physiology & Behavior found that morning exposure to bright light can significantly decrease cortisol levels later in the day, suggesting it helps anchor the entire 24-hour cycle. The opposite is also true. Evening exposure to artificial light, especially from electronic devices, provides a conflicting signal to the SCN.

Your master clock interprets this light as daylight, which can delay the natural decline of cortisol and the concurrent rise of melatonin, the hormone that facilitates sleep. This creates a state of circadian misalignment, where your internal hormonal environment is out of sync with the actual time of day.

A practical protocol involves seeking at least 20-30 minutes of direct, unfiltered sunlight within the first hour of waking. In the evening, the goal is to minimize blue light exposure for 1-2 hours before bed by using blue-light filtering software on devices, wearing blue-light blocking glasses, or opting for warm, red-hued ambient lighting.

Chrononutrition and Peripheral Clock Entrainment

While the SCN is the master clock, nearly every organ in your body, including your liver, pancreas, and digestive tract, has its own “peripheral” clock. These peripheral clocks are synchronized by the SCN, but they are also highly responsive to meal timing. This is the essence of chrononutrition.

When you eat, you activate the peripheral clocks in your metabolic organs. If you eat in alignment with the light-dark cycle ∞ consuming the majority of your calories during the day when your body is primed for digestion and glucose metabolism ∞ your peripheral clocks and master clock are in sync. This harmony supports a healthy cortisol rhythm.

A 2023 study in Frontiers in Nutrition highlighted that skipping breakfast was associated with lower awakening cortisol, indicating a blunted CAR. Consuming large meals late at night forces your metabolic organs to work when the SCN is signaling for rest, creating a state of internal conflict.

This can disrupt liver function, impair insulin sensitivity, and alter the natural overnight drop in cortisol. A time-restricted eating (TRE) window, where all calories are consumed within an 8-10 hour period during daylight hours, is a powerful way to enforce this synchrony. This gives the digestive system a prolonged daily rest period, which has been shown to improve metabolic markers and support HPA axis regulation.

- Breakfast Importance ∞ Consuming a protein-and-fat-rich breakfast within 60-90 minutes of waking helps to stabilize blood sugar and provides the correct metabolic signal to anchor the cortisol rhythm for the day.

- Front-Loading Calories ∞ Shifting a greater portion of your daily caloric intake to the first half of the day aligns with your body’s natural peak in insulin sensitivity and metabolic rate.

- Avoiding Late-Night Meals ∞ Finishing your last meal at least 3 hours before bedtime allows your digestive system to complete its work before your body enters its primary repair and recovery phase, preventing disruptions to cortisol and melatonin patterns.

Strategic Application of Exercise for HPA Modulation

Exercise is a potent modulator of cortisol, but its effects are highly dependent on intensity, duration, and timing. The body does not differentiate between sources of stress, so an intense workout is interpreted by the HPA axis in a similar way to a psychological stressor. The key is to apply this stressor at a time when it supports, rather than disrupts, your natural rhythm.

| Intervention Parameter | Morning Exercise (7-9 AM) | Evening Exercise (6-8 PM) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | To amplify the natural morning cortisol peak and reinforce a robust circadian rhythm. | To manage stress and improve physical fitness without disrupting sleep architecture. |

| Recommended Intensity | Moderate to high intensity (e.g. resistance training, interval training). | Low to moderate intensity (e.g. yoga, brisk walking, light resistance training). |

| Acute Cortisol Response | Causes a significant, but contextually appropriate, spike in cortisol that aligns with the natural peak. | Causes a cortisol spike that can be blunted compared to morning exercise, but still occurs when levels should be falling. |

| Effect on Diurnal Slope | Reinforces a steeper, healthier decline in cortisol throughout the afternoon and evening. | High-intensity sessions can flatten the diurnal slope by elevating evening cortisol levels. |

| Clinical Considerations | Ideal for individuals with morning fatigue or a blunted CAR. It helps to energize the system for the day ahead. | High-intensity evening workouts should be avoided by those with insomnia or high-stress levels, as it can worsen HPA dysregulation. |

What Is the Role of Stress Management in HPA Axis Regulation?

Chronic stress creates a feed-forward loop where the HPA axis becomes progressively less sensitive to the negative feedback of cortisol. The hypothalamus continues to send CRH signals, and the adrenal glands continue to produce cortisol, even when levels are already high. This leads to the flattened, dysfunctional curve seen in chronic stress and burnout.

Mind-body therapies are effective because they directly interrupt this cycle. Techniques like meditation and guided imagery have been shown in studies, including one from Psychoneuroendocrinology, to impact the stress response. These practices increase activity in the prefrontal cortex, the part of your brain responsible for executive function, which helps to down-regulate the amygdala, the brain’s fear center.

This calming of the amygdala reduces the initial stress signal sent to the hypothalamus, thereby quieting the entire HPA cascade. Regular practice can help restore the sensitivity of the HPA axis, allowing it to return to a more responsive, dynamic state.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of diurnal cortisol rhythm modification moves into the realm of molecular biology and neuroendocrinology. Lifestyle interventions are effective because they directly modulate the gene expression of core clock components and influence the neurochemical pathways that govern the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The alteration of the cortisol curve is a macroscopic reflection of microscopic changes in cellular timekeeping and intercellular signaling. Understanding these deep mechanisms provides a framework for designing highly targeted and potent wellness protocols.

Molecular Mechanisms of Circadian Entrainment

At the core of the circadian system is a set of clock genes, including CLOCK (Clock Circadian Regulator) and BMAL1 (Brain and Muscle Arnt-Like 1), which form a transcriptional-translational feedback loop that operates in virtually every cell. The proteins produced by these genes drive the rhythmic expression of thousands of other genes, governing everything from glucose metabolism to neurotransmitter synthesis.

The master clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is entrained primarily by photic information, which directly influences the expression of these clock genes. Light exposure in the morning activates the SCN, which then synchronizes the peripheral clocks in other tissues via both neural and hormonal signals, with cortisol being a primary hormonal messenger.

Chrononutrition works by directly engaging these peripheral clocks. For instance, the timing of food intake influences the expression of clock genes in the liver. When food is consumed out of sync with the light-dark cycle, the liver’s clock can become desynchronized from the SCN’s master clock.

This internal misalignment contributes to metabolic dysfunction and a disrupted HPA axis. A 2022 study on chrononutrition and pregnancy found that a longer eating window was associated with lower mean melatonin levels and that skipping breakfast was linked to a lower awakening cortisol level, demonstrating a direct, measurable link between meal timing and the rhythmic output of key hormones.

This suggests that meal timing is a powerful zeitgeber (time giver) for metabolic tissues, and aligning it with the SCN’s rhythm is critical for systemic homeostasis.

The daily rhythm of cortisol is a direct hormonal output of the body’s intricate, genetically-driven timekeeping system.

The Neurobiology of Light and HPA Axis Interaction

The influence of light on cortisol is mediated by a specific neural pathway ∞ the retinohypothalamic tract, which connects the intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) to the SCN. Research has shown that the spectral quality of light is a determining factor in its biological effect.

A 2023 systematic review in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences confirmed that exposure to bright light with stronger short-wavelength (blue/green) components in the early morning typically induced greater increases in cortisol relative to lights with stronger long-wavelength (red) components. This finding has profound implications for therapeutic light interventions.

The data suggests that morning light therapy should utilize bright, blue-enriched light to maximize its effect on the Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR). Conversely, evening environments should be dominated by long-wavelength light to prevent unwanted SCN stimulation and HPA axis activation.

Can the Wavelength of Light Affect Stress Response?

A study published in Stress investigated the effects of different light wavelengths on the cortisol response to an acute stressor. Healthy male subjects were exposed to bright white, dim white, red, or blue light after a standardized stress test. The results were compelling ∞ the bright white light exposure evoked the highest cortisol levels.

This indicates that light intensity is a critical variable in modulating the HPA axis’s reactivity to psychological stress. Living and working under constant, bright indoor lighting may prime the HPA axis for an exaggerated response to daily stressors, contributing to a state of chronic hypercortisolism.

| Intervention | Study Focus | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guided Imagery | A 12-week lifestyle intervention in adolescents. | The Lifestyle Behavior Guided Imagery (LBGI) group showed a small but significant increase in the Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR). | Weigensberg, M. J. et al. (2023) |

| Comprehensive Lifestyle Program | An 8-week program including diet, exercise, and stress management. | The program was suitable for improving metabolic parameters, but its direct effect on CAR was inconsistent, highlighting the complexity of stress measurement. | Kopp, R. et al. (2022) |

| Light Exposure Timing | Acute effects of bright light on cortisol levels. | Bright light exposure on the rising phase of the cortisol rhythm (early morning) significantly decreased cortisol levels later in the day. | Jung, C. M. et al. (2010) |

| Chrononutrition | Association of meal timing with melatonin and cortisol in pregnancy. | Skipping breakfast was associated with a lower awakening cortisol level, while a longer eating window was linked to lower overall melatonin. | Cheah, J. Q. et al. (2023) |

| Exercise Timing | Effects of morning vs. evening exercise on cortisol. | Cortisol concentrations in response to exercise peaked in the morning. Evening exercise resulted in a higher absolute cortisol level but a faster recovery. | Erdemir, I. (2017) |

The Pharmacology of Stress Reduction and HPA Axis Dampening

While lifestyle changes are foundational, certain compounds can support HPA axis regulation by modulating neurotransmitter activity and adrenal function. Phosphatidylserine (PS), a phospholipid that is a vital component of cell membranes, has been shown in clinical trials to blunt ACTH and cortisol responses to physical stress.

It is thought to work by supporting cell membrane function in the brain and may help to restore receptor sensitivity within the HPA axis feedback loop. Another agent, L-theanine, an amino acid found in green tea, promotes a state of calm alertness by increasing alpha brain wave activity and influencing neurotransmitters like GABA, dopamine, and serotonin.

This neurochemical shift can inhibit excessive cortical neuron excitation, thereby reducing the psychological perception of stress and decreasing the downstream activation of the HPA axis. These compounds function as adjuncts to a foundational lifestyle protocol, helping to dampen an overactive stress response system and create a more favorable internal environment for rhythm recalibration.

Ultimately, altering the diurnal cortisol rhythm is a process of re-establishing coherent communication across multiple biological systems. It requires the strategic application of powerful external cues ∞ light, food, and movement ∞ to entrain the body’s internal clocks. It also involves the conscious modulation of psychological stress to prevent chronic over-activation of the HPA axis.

The convergence of these interventions creates a synergistic effect, restoring the elegant, dynamic wave of cortisol that is essential for vitality, resilience, and optimal human function.

References

- Weigensberg, M. J. et al. “Changes in diurnal salivary cortisol patterns following a 12-week guided imagery RCT lifestyle intervention in predominantly Latino adolescents.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 151, 2023, p. 106053.

- Kopp, R. et al. “Eight Weeks of Lifestyle Change ∞ What are the Effects of the Healthy Lifestyle Community Programme (Cohort 1) on Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR) and Perceived Stress?” Journal of Personalized Medicine, vol. 12, no. 10, 2022, p. 1599.

- Adam, E. K. et al. “Diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes ∞ A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 83, 2017, pp. 25-41.

- Jung, C. M. et al. “Acute Effects of Bright Light Exposure on Cortisol Levels.” Journal of Biological Rhythms, vol. 25, no. 3, 2010, pp. 208-216.

- Cheah, J. Q. et al. “Chrononutrition is associated with melatonin and cortisol rhythm during pregnancy ∞ Findings from MY-CARE cohort study.” Frontiers in Nutrition, vol. 9, 2023, p. 1078086.

- Erdemir, Ibrahim. “Effects of Exercise on Circadian Rhythms of Cortisol.” Journal of Education and Training Studies, vol. 5, no. 4, 2017, pp. 69-74.

- Thoen, J. et al. “The effects of light exposure on the cortisol stress response in human males.” Stress, vol. 24, no. 6, 2021, pp. 749-757.

- Figueiro, Mariana G. and Mark S. Rea. “Lack of short-wavelength light during the school day delays dim light melatonin onset (DLMO) in middle school students.” Neuroendocrinology Letters, vol. 31, no. 1, 2010, pp. 92-96.

- García, Héctor, and Francesc Miralles. Ikigai ∞ The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life. Penguin Books, 2017.

- Scheer, Frank A. J. L. et al. “Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 106, no. 11, 2009, pp. 4453-4458.

Reflection

Where Does Your Journey Begin

The information presented here provides a map of the biological territory, connecting the symptoms you feel to the systems that produce them. It outlines the pathways through which your daily actions speak to your deepest physiology. This knowledge is the starting point.

The feeling of persistent fatigue or late-night anxiety is a personal signal, an invitation to look closer at the rhythms of your own life. Consider the first light you see in the morning, the timing of your meals, the movement of your body, and the texture of your thoughts.

Each element is a dial you can begin to adjust. The path to reclaiming your vitality is a process of self-discovery, guided by an understanding of your own unique biology. The ultimate goal is to move from a state of passive experience to one of active, informed participation in your own health.