Fundamentals

The feeling that your body is operating under a new set of rules is a tangible, valid experience. This internal shift, often felt as changes in energy, mood, or physical resilience, has a silent counterpart within your skeletal system. The architecture of your bones is undergoing a profound transformation, directly linked to the fluctuating and declining levels of estrogen.

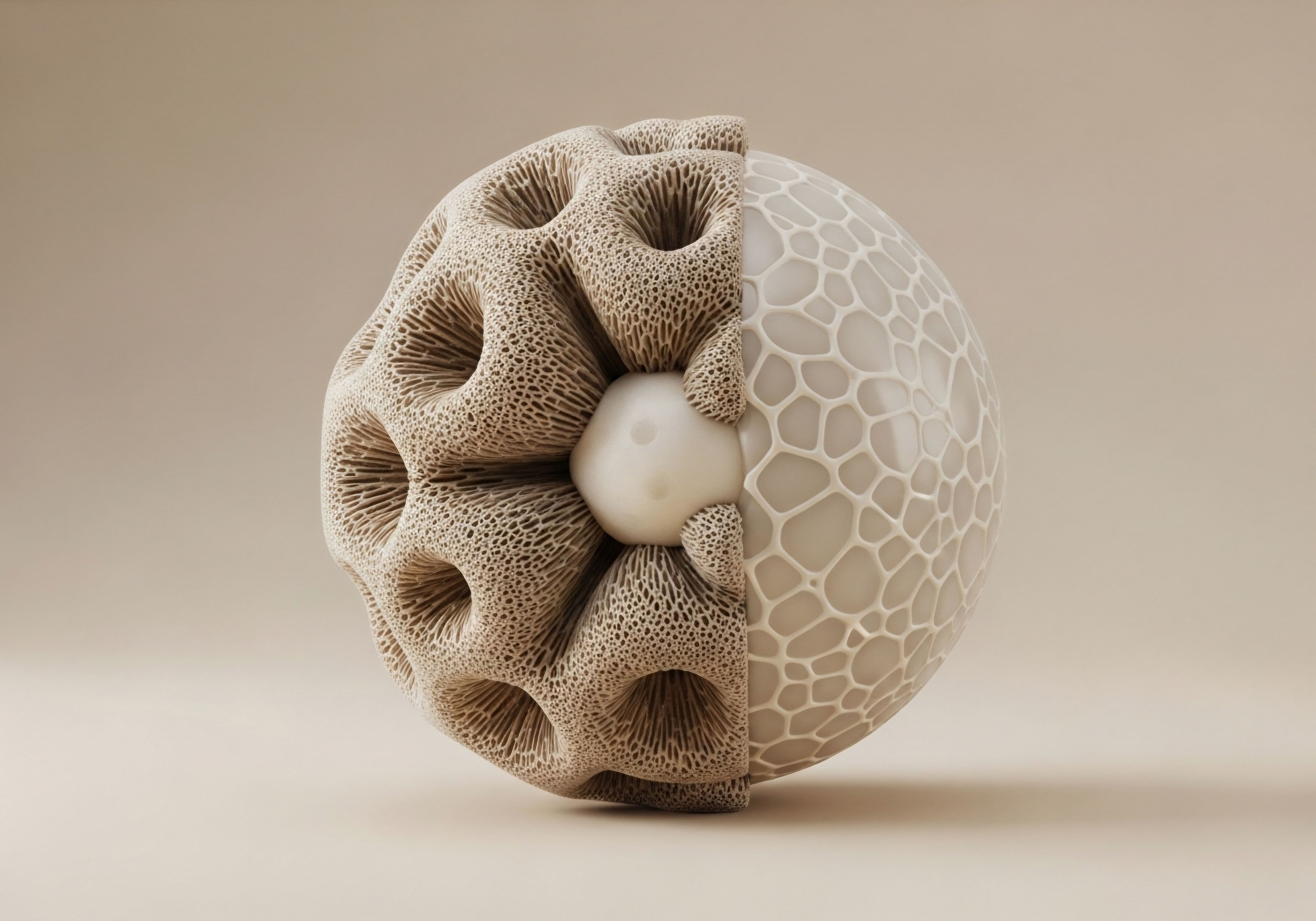

Understanding this process is the first step toward actively participating in your own structural health. Your bones are living, dynamic tissue, constantly being remodeled by two specialized cell types ∞ osteoblasts, which build new bone, and osteoclasts, which clear away old bone. Estrogen is a master regulator of this delicate balance, acting as a brake on osteoclast activity.

As estrogen levels decline, this braking system becomes less effective, and the rate of bone removal begins to outpace the rate of bone formation. This is the biological reality behind the clinical term “bone loss.”

The Blueprint of Bone Health

Think of your skeleton as a meticulously managed calcium savings account. Throughout your younger years, you make consistent deposits through diet and exercise, building a strong, dense reserve. Estrogen helps protect this principal balance.

When estrogen wanes, as it does during perimenopause and menopause, or when it is suppressed for medical reasons, the body begins to make more frequent withdrawals from this account to meet its physiological needs for calcium. Without intervention, the account balance, which represents your bone mineral density, gradually depletes.

This depletion is what increases fracture risk over time. The process is quiet and without sensation, yet its consequences are significant. The goal of intervention is to regain control over this internal economy, slowing withdrawals and stimulating new deposits.

What Is Estrogen’s Role in Bone Integrity?

Estrogen’s influence on bone is profound and multifaceted. Its primary function is to promote the survival of osteoblasts, the bone-building cells, while simultaneously inducing the self-destruction of osteoclasts, the bone-resorbing cells. This dual action ensures that the remodeling process remains in a state of equilibrium, where bone formation keeps pace with bone breakdown.

When estrogen is present in sufficient amounts, it effectively preserves skeletal mass. The decline of this hormone removes a key protective signal, tipping the scales in favor of resorption. This creates a state where bone is broken down faster than it can be rebuilt, leading to a net loss of density and a weakening of the bone’s internal architecture.

Intermediate

While hormonal shifts initiate the process of bone density change, targeted lifestyle interventions provide a powerful, non-pharmacological strategy to counteract these effects. These are not passive suggestions; they are active biological signals that you can send to your skeletal system. The two primary pillars of this strategy are specific forms of physical exercise and precise nutritional support.

When combined, they create an environment that encourages bone preservation and formation, directly opposing the catabolic state induced by estrogen suppression. These interventions work by providing the raw materials and the mechanical stimulus necessary for bone tissue to adapt and strengthen.

Lifestyle interventions work by providing both the physical stimuli and the essential nutrients required to encourage bone preservation and remodeling.

Mechanical Loading and Bone Adaptation

Your bones respond directly to the forces they encounter. The principle of mechanical loading is central to reversing bone density changes. Specific types of exercise create stress and strain on the skeleton, which is interpreted by bone cells as a signal to reinforce the structure. This process is known as mechanotransduction. Weight-bearing and resistance exercises are the most effective modalities for this purpose.

Engaging in these activities communicates a direct demand to your bones to become stronger. The impact from a brisk walk or the tension from a resistance band sends a message to osteocytes, the command-and-control cells embedded within the bone matrix.

These cells then orchestrate an increase in osteoblast activity, laying down new bone tissue in response to the perceived mechanical need. Consistency and progressive overload are key principles; the stimulus must be regular and challenging enough to continually prompt adaptation.

Types of Effective Exercise

- Weight-Bearing Exercise ∞ This category includes activities where your bones and muscles work against gravity. High-impact versions include running, jumping, and high-intensity interval training. Low-impact options, suitable for a wider range of fitness levels, include brisk walking, stair climbing, and using an elliptical machine.

- Resistance Training ∞ This involves moving your body against some form of resistance. Examples include using free weights, weight machines, resistance bands, or your own body weight (e.g. squats, push-ups). This type of exercise is particularly effective at targeting specific areas, such as the hips and spine, which are vulnerable to osteoporotic fractures.

- Balance and Postural Exercises ∞ Activities like yoga and Tai Chi improve proprioception, stability, and coordination. While they may not build bone density as robustly as impact exercises, they significantly reduce the risk of falls, which are the primary cause of fractures in individuals with low bone density.

Nutritional Architecture for Skeletal Health

Exercise provides the stimulus for bone growth, while nutrition provides the essential building blocks. A diet optimized for skeletal health focuses on delivering adequate amounts of specific minerals and vitamins that are critical for the bone formation cycle. Without these key nutrients, the body cannot effectively respond to the mechanical signals generated by physical activity.

| Nutrient | Primary Role in Bone Health | Dietary Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium | Forms the primary mineral component of the bone matrix, providing rigidity and strength. | Dairy products (yogurt, cheese), fortified plant milks, leafy greens (kale, collards), tofu, sardines. |

| Vitamin D | Facilitates the absorption of calcium from the intestine and its integration into the skeleton. | Sunlight exposure, fatty fish (salmon, mackerel), fortified foods (milk, cereals), egg yolks. |

| Protein | Constitutes about 50% of bone volume, creating the collagen framework that minerals adhere to. | Lean meats, poultry, fish, eggs, legumes, dairy, soy products. |

| Magnesium | Contributes to the structure of the bone crystal lattice and influences osteoblast activity. | Nuts (almonds, cashews), seeds (pumpkin, chia), spinach, black beans, whole grains. |

Academic

A comprehensive examination of reversing bone density changes from estrogen suppression requires a deep analysis of the cellular and molecular mechanisms at play. The process of bone remodeling is governed by the intricate crosstalk between osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteocytes. Estrogen’s primary role within this system is the regulation of signaling molecules known as cytokines.

Specifically, estrogen limits the production of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), a potent stimulator of osteoclast formation and activity, while promoting osteoprotegerin (OPG), a decoy receptor that neutralizes RANKL. The loss of estrogen disrupts this delicate RANKL/OPG ratio, leading to a state of unchecked osteoclastogenesis and accelerated bone resorption. Lifestyle interventions, particularly targeted physical loading, can directly modulate these signaling pathways, offering a mechanistic pathway to mitigate bone loss.

The mechanical forces generated during targeted exercise can directly influence the biochemical signaling pathways that govern bone cell activity.

Mechanotransduction the Cellular Response to Loading

The ability of bone to adapt its structure in response to mechanical demand is a process called mechanotransduction. Osteocytes, which are terminally differentiated osteoblasts entrapped within the bone matrix, function as the primary mechanosensors. When subjected to mechanical strain from weight-bearing exercise, the fluid within the lacunar-canalicular network of bone shifts, creating shear stress.

This physical stimulus is converted by osteocytes into biochemical signals. These signals include the release of nitric oxide and prostaglandins, which suppress sclerostin, a protein that inhibits bone formation. By downregulating sclerostin, osteocytes effectively release the brakes on osteoblast activity, promoting the laying down of new bone matrix. This cellular-level response demonstrates how a physical intervention like exercise can produce a specific, targeted anabolic effect on the skeleton.

How Do Lifestyle Factors Influence the Inflammatory Milieu?

The decline in estrogen fosters a pro-inflammatory environment characterized by elevated levels of cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). These inflammatory molecules further stimulate RANKL expression, exacerbating the cycle of bone resorption. Lifestyle interventions can alter this systemic inflammatory state.

For instance, regular physical activity has been shown to have an anti-inflammatory effect, reducing circulating levels of these cytokines. Similarly, a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants can help modulate inflammatory pathways. By reducing the systemic inflammatory load, these lifestyle choices can indirectly improve the RANKL/OPG ratio, making the bone microenvironment less conducive to resorption and more favorable to formation.

Can Lifestyle Alone Fully Reverse Established Bone Loss?

The question of complete reversal is complex. For individuals with significant osteoporosis resulting from prolonged estrogen suppression, lifestyle interventions alone are typically insufficient to restore bone mineral density to pre-menopausal levels. Clinical studies show that while structured exercise programs can increase BMD by a few percentage points, this effect is most pronounced when combined with pharmacological therapies, such as hormone replacement or bisphosphonates.

However, for individuals in the early stages of bone loss (osteopenia) or as a preventative strategy, a dedicated lifestyle protocol can be remarkably effective. It can halt the progression of bone loss and, in some cases, produce modest but clinically meaningful increases in density.

The primary value of these interventions lies in their ability to reduce fracture risk, which is a product of bone density, bone quality, muscle strength, and balance ∞ all of which are positively influenced by diet and exercise.

| Intervention | Cellular/Molecular Effect | Clinical Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| High-Impact Exercise | Increases fluid shear stress, downregulates sclerostin, promotes osteocyte viability. | Increases in bone formation markers (e.g. P1NP), potential for BMD increase at loaded sites. |

| Resistance Training | Creates localized strain, stimulates periosteal bone apposition. | Improves bone geometry and strength, increases muscle mass and stability. |

| Adequate Calcium/Vitamin D | Suppresses parathyroid hormone (PTH) secretion, reducing PTH-mediated bone resorption. | Provides substrate for mineralization, supports efficacy of other interventions. |

| Anti-inflammatory Diet | Reduces circulating levels of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α. | Shifts the RANKL/OPG balance in favor of OPG, creating a less resorptive bone environment. |

References

- Kour, Amrita, et al. “Effect of Lifestyle Modification Intervention Programme on Bone Mineral Density among Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis.” Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, vol. 17, no. 8, 2023, pp. LC06-LC10.

- Endocrine Society. “Menopause and Bone Loss.” endocrine.org, 24 Jan. 2022.

- Seibel, Mache. The Estrogen Fix and Your Bones. Savant Books and Publications, 2016.

- Hamoda, H. et al. “Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in women.” Post Reproductive Health, vol. 23, no. 4, 2017, pp. 180-195.

- Nall, Rachel. “7 Ways to Keep Your Bones Strong Through Breast Cancer Treatment.” Healthline, 28 Mar. 2022.

Reflection

You have now explored the intricate relationship between your hormonal state and your skeletal strength. This knowledge shifts the dynamic from one of passive experience to one of active partnership with your own biology. The information presented here is a map, detailing the terrain of your internal world and the pathways available for you to influence it.

Consider where you are on this map. What physical signals is your body sending? What nutritional messages are you providing it each day? The path forward is a personal one, built upon the foundation of this clinical understanding. The next step is to translate this knowledge into a sustainable, personalized protocol, a conversation that begins with self-awareness and continues with informed, proactive choices about your health trajectory.