Fundamentals

You may feel it as a subtle shift in your daily energy, a frustrating plateau in your fitness goals, or a confusing change in your mood and cognitive clarity. These experiences are valid and deeply personal, and they often represent the body’s attempt to communicate a deeper truth about its internal environment.

Your biology is speaking a complex language, and one of its most important words is Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin, or SHBG. Understanding this single protein is a foundational step in translating your body’s signals into a coherent plan for reclaiming your vitality. It provides a window into the intricate workings of your endocrine system, revealing how the lifestyle choices you make each day are directly received and interpreted by your cells.

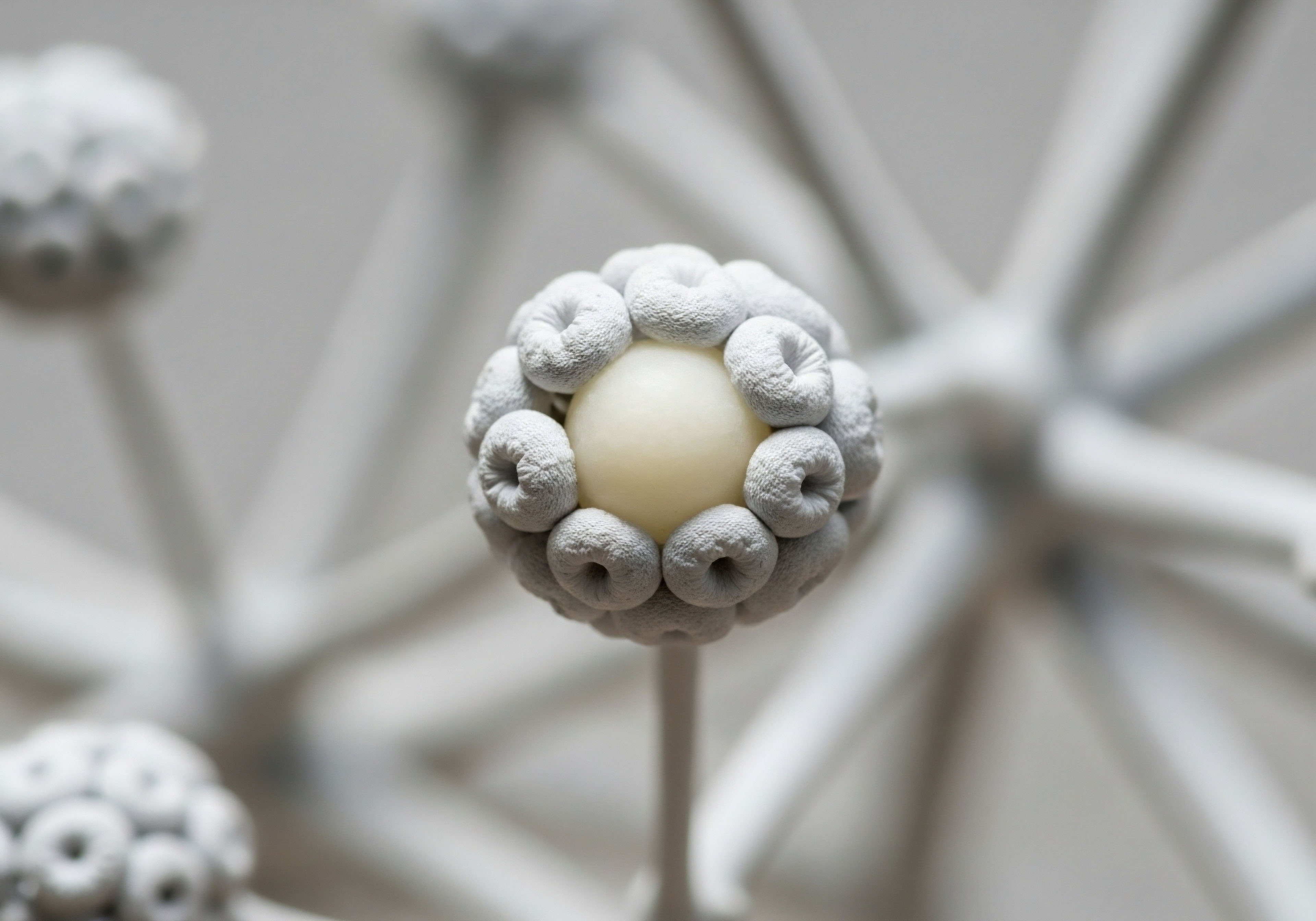

SHBG is a glycoprotein produced primarily by the liver. Its main function is to act as a transport vehicle for your sex hormones, particularly testosterone and estradiol, as they travel through the bloodstream. Think of it as a specialized ferry service. When a hormone is bound to SHBG, it is inactive, held in reserve.

Only the hormones that are “free,” or unbound, are biologically available to enter your cells, bind to receptors, and exert their powerful effects on your tissues, brain, and metabolism. The concentration of SHBG in your blood, therefore, directly dictates the amount of active hormones your body can actually use. A higher level of SHBG means fewer free hormones, while a lower level results in more of them being available for cellular action.

Your SHBG level acts as a primary regulator of sex hormone availability, directly influencing cellular function and overall vitality.

This regulation is the core of its importance. The balance between bound and free hormones affects everything from libido and muscle maintenance to cognitive function and mood stability. When this balance is disrupted, the symptoms you experience are real and rooted in this biochemical reality.

The journey to understanding your health requires moving past a surface-level view of hormone levels and looking at the systems that control their availability. SHBG is a key piece of that deeper puzzle, and its levels tell a story about much more than just your sex hormones.

What Story Is Your SHBG Level Telling?

Your SHBG concentration is a sensitive indicator of your broader metabolic health. Its production in the liver is not isolated; it is profoundly influenced by other powerful systemic signals. The amount of SHBG your liver synthesizes is a direct response to the metabolic state of your body.

This is where the power of lifestyle intervention becomes clear. Factors like your diet, exercise habits, stress levels, and sleep quality send constant information to your liver, instructing it to either increase or decrease SHBG production. Therefore, your SHBG level can be seen as a reflection of your liver’s health, your body’s sensitivity to insulin, and the overall state of your endocrine system.

For instance, one of the most powerful regulators of SHBG is insulin. When your diet is high in refined carbohydrates and sugars, your body releases large amounts of insulin to manage blood glucose. Chronically high insulin levels send a strong signal to the liver to suppress the production of SHBG.

This results in lower SHBG levels, which in turn increases the amount of free testosterone and estrogen. In certain contexts, this can contribute to conditions like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) in women or create imbalances in androgen-to-estrogen ratios in men. Conversely, factors that improve insulin sensitivity, such as a high-fiber diet and regular physical activity, tend to support healthier SHBG levels. This connection demonstrates that modulating SHBG is an outcome of addressing foundational metabolic health.

The Interconnected Endocrine Web

Your body’s hormonal systems function as an interconnected web of communication. SHBG is influenced by more than just insulin. Thyroid hormones, for example, also play a significant role. An overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism) can lead to elevated SHBG levels, while an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) is often associated with lower SHBG.

This is because thyroid hormones directly stimulate the gene in your liver cells that is responsible for producing SHBG. This highlights the importance of a comprehensive assessment. An abnormal SHBG level might be one of the first indicators that prompts a deeper investigation into thyroid function.

Furthermore, the sex hormones themselves participate in a feedback loop with SHBG. Estrogens tend to stimulate SHBG production, which is one reason why women naturally have higher levels than men. Androgens like testosterone, on the other hand, tend to suppress its production.

This intricate system of checks and balances is designed to maintain homeostasis, a state of internal stability. When you engage in lifestyle interventions, you are not just targeting a single number on a lab report. You are influencing the entire communication network. By improving your diet, you are changing the insulin signals sent to your liver.

By managing stress, you are altering cortisol patterns that affect the entire endocrine cascade. These actions collectively recalibrate the system, and a balanced SHBG level is one of the positive results of that systemic healing.

Intermediate

Understanding that lifestyle choices can influence SHBG is the first step. The next is to explore the specific, actionable protocols that can be used to modulate its levels and, by extension, optimize hormonal bioavailability for long-term health.

This involves a more granular look at the biochemical signals generated by diet, exercise, and stress management, and how these signals are interpreted by the liver to regulate SHBG synthesis. The goal is to move from general wellness advice to a targeted, evidence-based strategy that addresses the root causes of SHBG dysregulation. This approach empowers you to use lifestyle as a precise tool for biological recalibration.

The modulation of SHBG is fundamentally a conversation between your lifestyle and your liver. The primary leverage point in this conversation is insulin. As established, insulin is a potent suppressor of SHBG gene transcription. Therefore, any intervention that stabilizes blood glucose and improves insulin sensitivity will have a direct, favorable impact on SHBG levels, particularly for individuals with low SHBG due to metabolic dysfunction.

This is the biological mechanism behind why dietary choices are so effective. A diet centered around whole, unprocessed foods provides a slow release of glucose, preventing the sharp insulin spikes that downregulate SHBG production. This is the foundation upon which more specific interventions can be built.

How Does Diet Directly Signal the Liver?

Dietary composition sends clear instructions to the liver, influencing not only insulin levels but also hepatic fat accumulation and inflammation, all of which affect SHBG synthesis. A diet rich in fiber, for instance, slows down carbohydrate absorption, mitigating post-meal insulin surges. Soluble fiber, found in foods like oats, flaxseeds, and legumes, is particularly effective.

Similarly, the type of fat consumed is important. Diets high in saturated fats can contribute to hepatic insulin resistance, further suppressing SHBG. Replacing these with monounsaturated fats (found in olive oil and avocados) and omega-3 fatty acids (found in fatty fish) can improve liver function and insulin signaling pathways.

Protein intake also plays a role, although its effects can be context-dependent. Some research suggests that higher protein diets may be associated with lower SHBG levels. This could be beneficial for individuals with excessively high SHBG who are experiencing symptoms of low free hormones, such as low libido or fatigue.

The mechanism may be related to the mild insulinogenic effect of some amino acids or other complex metabolic pathways. This highlights the need for personalization. An individual with low SHBG and insulin resistance would focus on fiber and healthy fats, whereas someone with high SHBG might experiment with increasing their protein intake while monitoring their symptoms and lab values.

Strategic dietary changes, particularly those that improve insulin sensitivity and liver health, are the most powerful lifestyle tool for modulating SHBG production.

The following table outlines dietary strategies based on the goal of either increasing or decreasing SHBG levels, keeping in mind that these are general frameworks that should be adapted to an individual’s unique physiology.

| Modulation Goal | Primary Dietary Strategy | Key Foods and Nutrients | Underlying Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increase Low SHBG | Low-Glycemic, High-Fiber Diet | Leafy greens, legumes, whole grains, flaxseeds, nuts, berries. | Improves insulin sensitivity, reduces hepatic insulin exposure, and slows glucose absorption, which removes the suppressive signal on SHBG synthesis. |

| Decrease High SHBG | Increased Protein and Healthy Fats | Lean meats, fish, eggs, olive oil, avocados, seeds. | May help lower SHBG by providing essential nutrients and potentially through mild insulinogenic effects of protein, increasing free hormone availability. |

Exercise Protocols for Hormonal Recalibration

Physical activity is another potent modulator of SHBG, primarily through its effects on insulin sensitivity and body composition. Regular exercise makes muscle cells more receptive to glucose, meaning the body needs to produce less insulin to manage blood sugar. This reduction in circulating insulin alleviates the suppressive pressure on the liver’s SHBG production.

The type of exercise matters:

- Aerobic Exercise ∞ Activities like brisk walking, running, cycling, and swimming have been consistently shown to improve insulin sensitivity and are associated with increases in SHBG levels. The sustained, moderate-intensity effort enhances glucose uptake by muscles and promotes long-term metabolic health.

- Resistance Training ∞ Lifting weights or performing bodyweight exercises builds muscle mass. Since muscle is a primary site for glucose disposal, having more muscle mass improves overall glycemic control, which indirectly supports healthy SHBG levels.

- High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) ∞ Short bursts of intense effort followed by brief recovery periods can produce significant improvements in insulin sensitivity in a time-efficient manner, offering another effective strategy for supporting SHBG production.

It is important to recognize that over-exercising combined with significant calorie restriction can sometimes lead to excessively high SHBG levels. This state, often seen in endurance athletes, is the body’s adaptive response to a perceived energy deficit. The hypothalamus may reduce hormonal signals to conserve energy, and the resulting hormonal environment can lead to an increase in SHBG.

This underscores the importance of balance. The goal is a sustainable exercise routine that promotes metabolic health without creating undue physiological stress.

The Role of Micronutrients and Supplements

While whole-food dietary patterns are foundational, certain micronutrients and supplements can provide targeted support for SHBG modulation. These should be considered as adjuncts to a solid lifestyle foundation, and their use is best guided by lab testing and clinical consultation.

- Boron ∞ This trace mineral has been shown in some studies to decrease SHBG levels, thereby increasing free testosterone. It appears to interfere with the binding of sex hormones to SHBG, although its exact mechanism is still being explored. It is a tool that may be considered for individuals with confirmed high SHBG.

- Zinc ∞ Essential for hundreds of enzymatic reactions, zinc is also crucial for reproductive health. Some research indicates that zinc supplementation may help lower elevated SHBG levels and improve testosterone bioavailability, particularly in men. Oysters, red meat, and pumpkin seeds are good dietary sources.

- Magnesium ∞ This mineral is a critical cofactor in glucose metabolism and insulin signaling. Ensuring adequate magnesium intake through foods like leafy greens, nuts, and seeds, or through supplementation, can support the insulin sensitivity that is foundational to healthy SHBG levels.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of SHBG modulation requires moving beyond lifestyle correlations to a deep examination of the molecular and metabolic pathways that govern its synthesis. The central arena for this regulation is the hepatocyte, the primary cell of the liver.

Here, the expression of the SHBG gene is controlled by a complex interplay of nuclear transcription factors, hormonal signals, and metabolic inputs. Lifestyle interventions are effective precisely because they systematically alter these inputs. The most dominant and clinically relevant pathway to explore is the intricate relationship between adiposity, insulin resistance, and hepatic SHBG gene expression, as this axis is central to many modern metabolic diseases.

The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), a landmark multicenter clinical trial, provides profound insights into this relationship. The study randomized individuals at high risk for type 2 diabetes into three groups ∞ an intensive lifestyle intervention (ILS) group, a metformin group, and a placebo group.

A secondary analysis of this trial revealed that the ILS group experienced the most significant and favorable changes in SHBG levels. Specifically, SHBG levels increased in postmenopausal women and the typical age-related decline was attenuated in men and premenopausal women. This finding confirms that lifestyle modification is a powerful tool for SHBG modulation.

The effectiveness of lifestyle interventions on SHBG is primarily mediated through their impact on adiposity and insulin sensitivity, highlighting SHBG as a key biomarker of systemic metabolic health.

The same study, however, delivered a second, equally important finding. When the researchers adjusted the data for changes in adiposity (body fat), the association between the lifestyle intervention and SHBG changes was significantly weakened. This demonstrates that the primary mechanism through which lifestyle changes influenced SHBG was by reducing body fat and improving the associated metabolic dysfunction.

The study concluded that changes in SHBG did not independently predict the reduction in diabetes risk once changes in adiposity were accounted for. This positions SHBG as an exceptionally sensitive and valuable biomarker of metabolic improvement, even if it is not an independent causal agent in the prevention of diabetes in this high-risk population. It reflects the health of the system rather than driving it in isolation.

Do Changes in SHBG Directly Mediate Health Outcomes?

The molecular regulation of the SHBG gene within the hepatocyte provides a clear explanation for these clinical findings. The key promoter of SHBG gene transcription is a nuclear receptor known as Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4-alpha (HNF-4α). This transcription factor acts as a master regulator of many genes involved in liver function.

Thyroid hormones and estrogens tend to upregulate HNF-4α activity, leading to increased SHBG production. This is the molecular basis for the higher SHBG levels seen in hyperthyroidism and during pregnancy.

Conversely, the single most potent suppressor of HNF-4α-mediated SHBG transcription is insulin. In a state of hyperinsulinemia, characteristic of insulin resistance and obesity, the chronically elevated insulin levels activate signaling pathways within the hepatocyte that inhibit HNF-4α’s ability to bind to the SHBG gene promoter.

This directly reduces SHBG synthesis, leading to the low SHBG levels commonly observed in individuals with metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and PCOS. Inflammatory cytokines, such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), which are often elevated in states of obesity, also contribute to the suppression of SHBG production. Lifestyle interventions, by reducing adiposity and inflammation and improving insulin sensitivity, directly reverse this suppression, allowing HNF-4α to resume its role in promoting SHBG synthesis.

The following table details the molecular inputs that regulate hepatic SHBG gene expression, providing a systems-biology perspective on its modulation.

| Input Signal | Primary Source | Effect on SHBG Synthesis | Core Molecular Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin | Pancreas (in response to glucose) | Suppression | Inhibits the activity of the transcription factor HNF-4α, a key activator of the SHBG gene. |

| Estrogens | Ovaries, Adipose Tissue | Stimulation | Upregulates the expression and activity of HNF-4α, leading to increased SHBG transcription. |

| Androgens | Testes, Ovaries, Adrenals | Suppression | Appears to directly or indirectly downregulate SHBG gene expression, independent of HNF-4α in some cases. |

| Thyroid Hormone (T3) | Thyroid Gland | Stimulation | Directly enhances the binding of HNF-4α to the SHBG gene promoter region, increasing transcription. |

| Inflammatory Cytokines (e.g. TNF-α) | Adipose Tissue, Immune Cells | Suppression | Contributes to hepatic insulin resistance and directly inhibits HNF-4α activity. |

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Perspective

This deep understanding of SHBG regulation has profound clinical implications. For a woman presenting with symptoms of PCOS, such as hirsutism and irregular cycles, a low SHBG level is a key diagnostic finding. It confirms a state of hyperandrogenism (excess free testosterone) and points directly to underlying insulin resistance as the primary therapeutic target.

Lifestyle interventions focusing on a low-glycemic diet and regular exercise are, therefore, first-line treatments because they address the root cause of the hormonal imbalance by improving insulin sensitivity and allowing SHBG levels to normalize.

For a man undergoing evaluation for hypogonadism, SHBG is a critical part of the assessment. A low total testosterone level may be misleading if SHBG is also very low, as the free, bioavailable testosterone might still be adequate.

Conversely, a normal total testosterone level could mask a functional deficiency if SHBG is excessively high, leaving very little free testosterone available to the tissues. Interventions aimed at modulating SHBG can be essential for restoring proper hormonal function.

For example, if a man has high SHBG and low free testosterone, strategies to moderately lower SHBG, such as increasing protein intake or considering specific micronutrients like boron, could be clinically beneficial alongside addressing any underlying causes like hyperthyroidism or extreme caloric restriction. This nuanced, systems-based approach, grounded in the molecular physiology of the liver, allows for truly personalized and effective hormonal health protocols.

References

- Kim, C. et al. “Circulating sex hormone binding globulin levels are modified with intensive lifestyle intervention, but their changes did not independently predict diabetes risk in the Diabetes Prevention Program.” BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care, vol. 8, no. 2, 2020, e001608.

- Wallace, I. R. et al. “Sex hormone binding globulin and insulin resistance.” Clinical Endocrinology, vol. 78, no. 3, 2013, pp. 321-329.

- Hammond, Geoffrey L. “Diverse roles for sex hormone-binding globulin in reproduction.” Biology of Reproduction, vol. 95, no. 5, 2016, 114, 1-9.

- Pugeat, M. et al. “Sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) ∞ from basic research to clinical applications.” Annales d’Endocrinologie, vol. 71, no. 3, 2010, pp. 191-198.

- Longcope, C. et al. “The effect of a high-protein diet on serum testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 82, no. 2, 1997, pp. 409-412.

- Selva, D. M. & Hammond, G. L. “Thyroid hormones and sex hormone-binding globulin.” Clinical Endocrinology, vol. 70, no. 1, 2009, pp. 22-28.

- Kalyani, R. R. et al. “Sex hormones, sex hormone-binding globulin, and diabetes mellitus.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 99, no. 11, 2014, pp. 4045-4054.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a map of the biological terrain governing your hormonal health. You have seen how a single protein, SHBG, serves as a sensitive barometer for the entire metabolic system, reflecting the language of your liver, the sensitivity of your cells to insulin, and the balance of your endocrine orchestra.

This knowledge is a powerful starting point. It transforms abstract feelings of being unwell into a set of understandable, interconnected systems that you can positively influence. The path forward involves taking this map and applying it to your unique context.

Your own health journey is a deeply personal narrative. The numbers on a lab report are simply characters in that story; they provide clues and context, but you are the author. The true work begins when you start to connect these biological data points to your lived experience.

How does your energy shift when you change your dietary patterns? How does your cognitive clarity improve with consistent, restorative sleep? This process of self-discovery, of becoming a careful observer of your own biology, is where lasting change is forged. Consider this knowledge not as a set of rigid rules, but as a toolkit for building a more resilient, responsive, and vital version of yourself, one intentional choice at a time.

Glossary

sex hormone-binding globulin

sex hormones

metabolic health

lifestyle intervention

your shbg level

that improve insulin sensitivity

polycystic ovary syndrome

associated with lower shbg

thyroid hormones

lifestyle interventions

hormonal bioavailability

shbg synthesis

insulin sensitivity

shbg levels

insulin resistance

improve insulin sensitivity

glycemic control

free testosterone

hepatic shbg gene expression

adiposity

shbg gene

hnf-4α

shbg gene expression