Fundamentals

You feel it in your bones. A pervasive sense of fatigue that sleep does not seem to touch, a mental fog that clouds your focus, and a general decline in vitality that feels premature and deeply personal. When you experience prolonged, unyielding stress, your body initiates a series of profound biological shifts designed for short-term survival.

The question of whether lifestyle changes can reverse the resulting hormonal suppression is a valid and pressing one. The answer, grounded in the elegant logic of your own physiology, is yes. It is possible because these interventions directly address the root cause ∞ the persistent, system-wide alert state that has silenced your body’s natural hormonal rhythms.

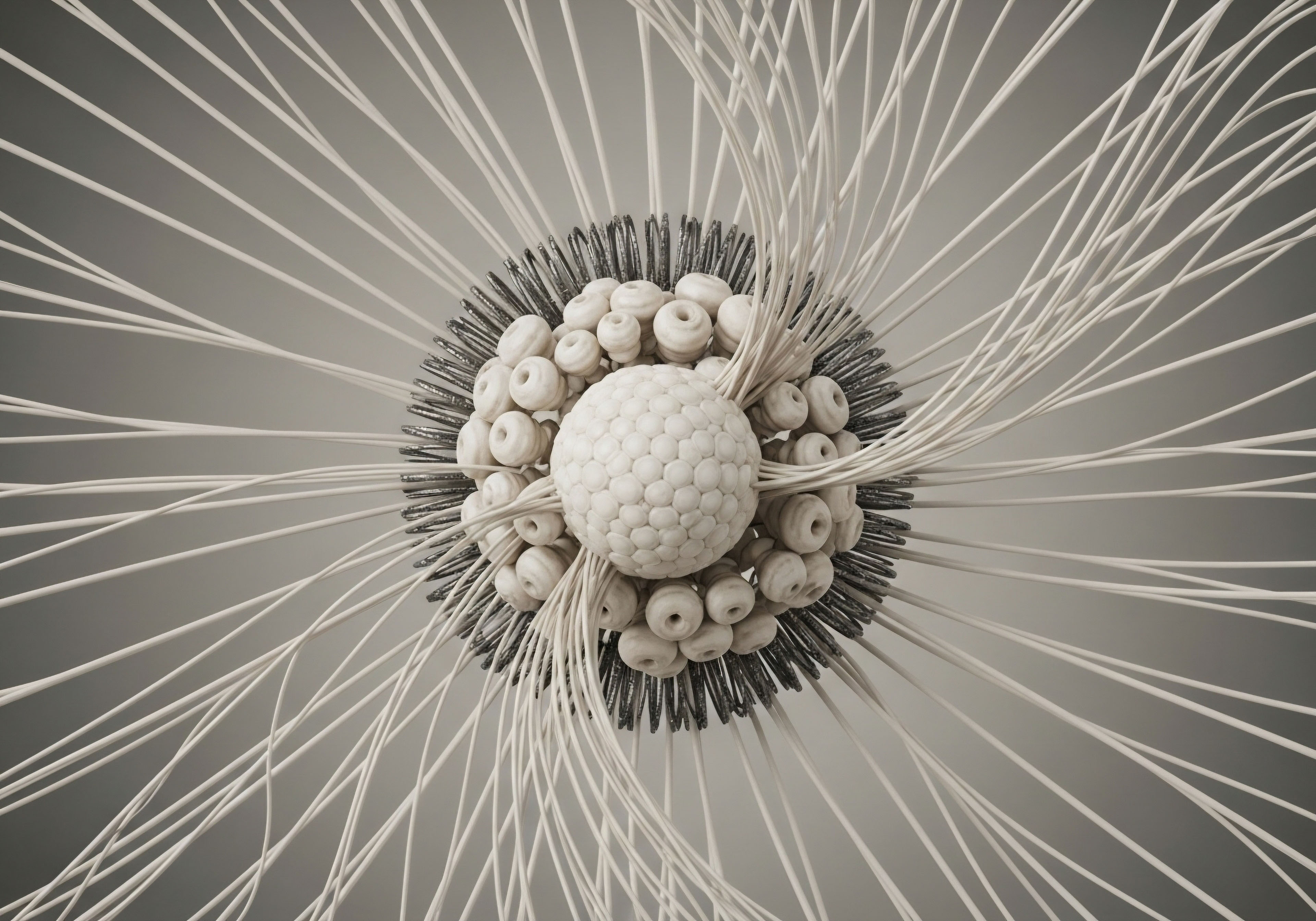

Understanding this process begins with appreciating the body’s internal command structure for hormonal health, known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Think of this as the central operating system for your reproductive and endocrine vitality. The hypothalamus, a small region at the base of your brain, acts as the mission commander.

It sends a critical signal, Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), to the pituitary gland. The pituitary, acting as the field general, receives this signal and, in response, releases two key hormones into the bloodstream ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH).

These hormones travel to the gonads (the testes in men and ovaries in women), instructing them to produce testosterone and other essential sex hormones. This entire system operates on a sophisticated feedback loop, ensuring hormonal levels remain balanced and appropriate for optimal function.

Now, introduce a significant stressor. Your body perceives a threat and activates a parallel, more ancient survival system ∞ the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. This is your emergency response network. The hypothalamus releases Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH), which signals the pituitary to secrete Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH).

ACTH then stimulates the adrenal glands, located atop your kidneys, to flood the body with cortisol. Cortisol is a powerful glucocorticoid hormone designed to mobilize energy, sharpen focus, and suppress non-essential functions to handle an immediate crisis. In the context of survival, functions like reproduction, long-term tissue repair, and robust immune activity are considered secondary. The body wisely prioritizes immediate survival over procreation.

Chronic stress creates a biological environment where survival signals consistently override the body’s systems for thriving and regeneration.

The problem arises when the stress is not a fleeting crisis but a chronic, unrelenting feature of modern life. The HPA axis remains perpetually activated, leading to chronically elevated cortisol levels. This is where the communication breakdown begins. High levels of cortisol and CRH send powerful inhibitory signals directly back to the hypothalamus, effectively telling it to silence the GnRH message.

The mission commander for your reproductive health is suppressed. Research also reveals another layer of this suppression through a hormone called Gonadotropin-Inhibitory Hormone (GnIH), which is stimulated by stress and acts as a direct brake on the HPG axis. The result is a top-down shutdown of your hormonal production line.

Lower GnRH leads to lower LH and FSH, which in turn means the gonads receive a weaker signal, producing less testosterone. This state is known as stress-induced functional hypogonadism. The system is not broken; it is suppressed by design as a protective, albeit costly, measure.

Lifestyle interventions work because they are the tools you can use to deactivate this chronic alarm. They do not just treat the symptoms of low testosterone; they recalibrate the entire signaling environment. Strategic nutrition provides the raw materials for hormone production. Specific forms of exercise modulate cortisol levels and improve insulin sensitivity.

Restorative sleep is perhaps the most critical element, as it is during deep sleep that the HPA axis resets itself, lowering cortisol and allowing the HPG axis to resume its natural, pulsatile signaling. By consciously managing these inputs, you are sending a powerful message back to your hypothalamus ∞ the crisis has passed. It is safe to invest in vitality again. This allows the suppressive influence of cortisol to recede, enabling the natural rhythm of your HPG axis to be restored.

Intermediate

To fully appreciate how lifestyle changes can reverse stress-induced hypogonadism, we must examine the specific mechanisms through which these interventions counteract the biological cascade initiated by chronic stress. This involves moving beyond a general understanding and into the practical application of diet, exercise, and sleep as potent tools for endocrine system recalibration.

The goal is to systematically dismantle the state of chronic alert and rebuild the foundation for robust hormonal health. Success hinges on consistency and a targeted approach that addresses the distinct physiological disruptions at play.

Deconstructing the Stress Response Pathway

The suppression of gonadal function under stress is a multi-pronged physiological event. Chronically elevated cortisol exerts its influence in several ways. First, it directly suppresses GnRH neurons in the hypothalamus, reducing the frequency and amplitude of GnRH pulses, which are essential for proper pituitary function.

Second, the associated release of CRH and endogenous opioids (like beta-endorphins) in response to stress also has a direct inhibitory effect on GnRH secretion. This creates a powerful dual-suppression system at the very top of the hormonal hierarchy.

Third, emerging research highlights the role of Gonadotropin-Inhibitory Hormone (GnIH), a peptide that acts as a direct antagonist to GnRH, further ensuring the reproductive axis is throttled down during perceived emergencies. Lifestyle interventions succeed by targeting these pathways, reducing the inhibitory signals and providing the necessary conditions for the HPG axis to resume normal operations.

How Can Sleep Architecture Directly Influence Hormonal Recovery?

Sleep is a fundamental pillar of hormonal regulation. Its absence or poor quality is a potent physiological stressor that directly impacts the HPA and HPG axes. The majority of daily testosterone release in men occurs during sleep, specifically tied to the deep, slow-wave stages. Sleep deprivation disrupts this process profoundly.

Studies have demonstrated that even one week of sleeping five hours per night can decrease daytime testosterone levels by 10-15% in healthy young men. This occurs for two primary reasons. First, lack of sleep prevents the natural overnight decline in cortisol, meaning you start the next day with a higher stress hormone baseline.

Second, the disruption of circadian rhythms desynchronizes the entire endocrine system, impairing the pituitary’s ability to release LH in its normal pulsatile pattern. Restoring a consistent sleep schedule of 7-9 hours per night is the most direct way to recalibrate this system.

- Sleep Hygiene Protocol ∞ This involves creating a strict routine. Go to bed and wake up at the same time daily, even on weekends. Ensure the bedroom is completely dark, quiet, and cool. Avoid blue light from screens for at least 90 minutes before bed, as it suppresses melatonin production and delays sleep onset.

- Cortisol Management ∞ Low testosterone can increase cortisol, which in turn fragments sleep, creating a vicious cycle. Engaging in relaxing pre-sleep activities like reading, meditation, or gentle stretching can help lower evening cortisol, facilitating easier entry into restorative deep sleep where hormonal recovery occurs.

Strategic Nutrition for Hormonal Synthesis

Your diet provides the essential building blocks for hormones and the cofactors needed for their synthesis. Chronic stress depletes key micronutrients and can lead to patterns of eating that further disrupt hormonal balance, such as overconsumption of refined carbohydrates and processed foods. A targeted nutritional strategy provides the raw materials for recovery.

A nutrient-dense diet acts as a direct input for hormonal production and a modulator of systemic inflammation.

The body synthesizes testosterone from cholesterol. Therefore, diets that are excessively low in fat can be detrimental to hormonal health. Research indicates that low-fat dietary patterns are associated with decreased testosterone levels. The focus should be on incorporating healthy fats while providing the necessary micronutrients for the enzymatic processes of hormone creation.

| Nutrient Category | Mechanism of Action | Primary Food Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy Fats | Provides the cholesterol backbone for steroid hormone synthesis. Omega-3s also reduce inflammation, which can impair endocrine function. | Avocados, olive oil, fatty fish (salmon, mackerel), nuts, and seeds. |

| Zinc | A critical mineral for the function of enzymes involved in testosterone production. Zinc deficiency is directly linked to hypogonadism. | Oysters, red meat, shellfish, pumpkin seeds, and lentils. |

| Vitamin D | Functions as a steroid hormone. Receptors for Vitamin D are found on cells in the hypothalamus, pituitary, and testes, indicating its role in regulating the HPG axis. | Fatty fish, fortified milk, egg yolks, and sensible sun exposure. |

| Magnesium | Associated with increased free and total testosterone levels, potentially by reducing the binding affinity of testosterone to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG). | Dark leafy greens (spinach, kale), nuts, seeds, and whole grains. |

Exercise as an Endocrine Modulator

Physical activity is a powerful tool for managing stress and improving hormonal health, but the type and intensity are critical. Exercise acts as a double-edged sword; the right amount can optimize your endocrine system, while too much can act as another chronic stressor.

Resistance training and high-intensity interval training (HIIT) have been shown to acutely increase testosterone levels. These forms of exercise stimulate a beneficial hormonal cascade that promotes muscle growth and improves insulin sensitivity, a key factor in metabolic and hormonal health. In contrast, excessive, prolonged endurance exercise without adequate caloric intake can elevate cortisol for extended periods and suppress the HPG axis, a condition often seen in overtrained male athletes. The key is to find a sustainable balance.

- Resistance Training ∞ Focus on compound movements like squats, deadlifts, and presses 2-4 times per week. This type of stimulus has been shown to be most effective at promoting a favorable testosterone-to-cortisol ratio.

- Moderate Aerobic Exercise ∞ Incorporate 30-45 minutes of moderate-intensity cardiovascular activity, such as brisk walking or cycling, on other days. This helps improve cardiovascular health and manage stress without significantly spiking cortisol.

- Active Recovery ∞ Prioritize rest days. This is when the body adapts and repairs. Chronic, daily high-intensity training without recovery will deepen the state of HPA axis dysfunction.

By implementing these specific, evidence-based lifestyle strategies, you are not merely hoping for an improvement. You are actively participating in the reversal of the physiological state of stress-induced hypogonadism. You are reducing the inhibitory load on your HPG axis, providing the necessary precursors for hormone synthesis, and restoring the natural rhythms required for optimal function.

Academic

The reversal of stress-induced hypogonadism through lifestyle modification is a compelling example of the neuroendocrine system’s plasticity. A deeper analysis requires an examination of the molecular interactions at the heart of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis and the systemic metabolic dysregulation that often accompanies a state of chronic stress.

This condition, more accurately termed functional hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, represents a state of adaptive, reversible suppression rather than organic pathology. The success of non-pharmacological interventions is predicated on their ability to modulate glucocorticoid signaling, restore metabolic homeostasis, and mitigate the allostatic load that silences reproductive endocrine function.

Molecular Mechanisms of Glucocorticoid-Induced HPG Axis Suppression

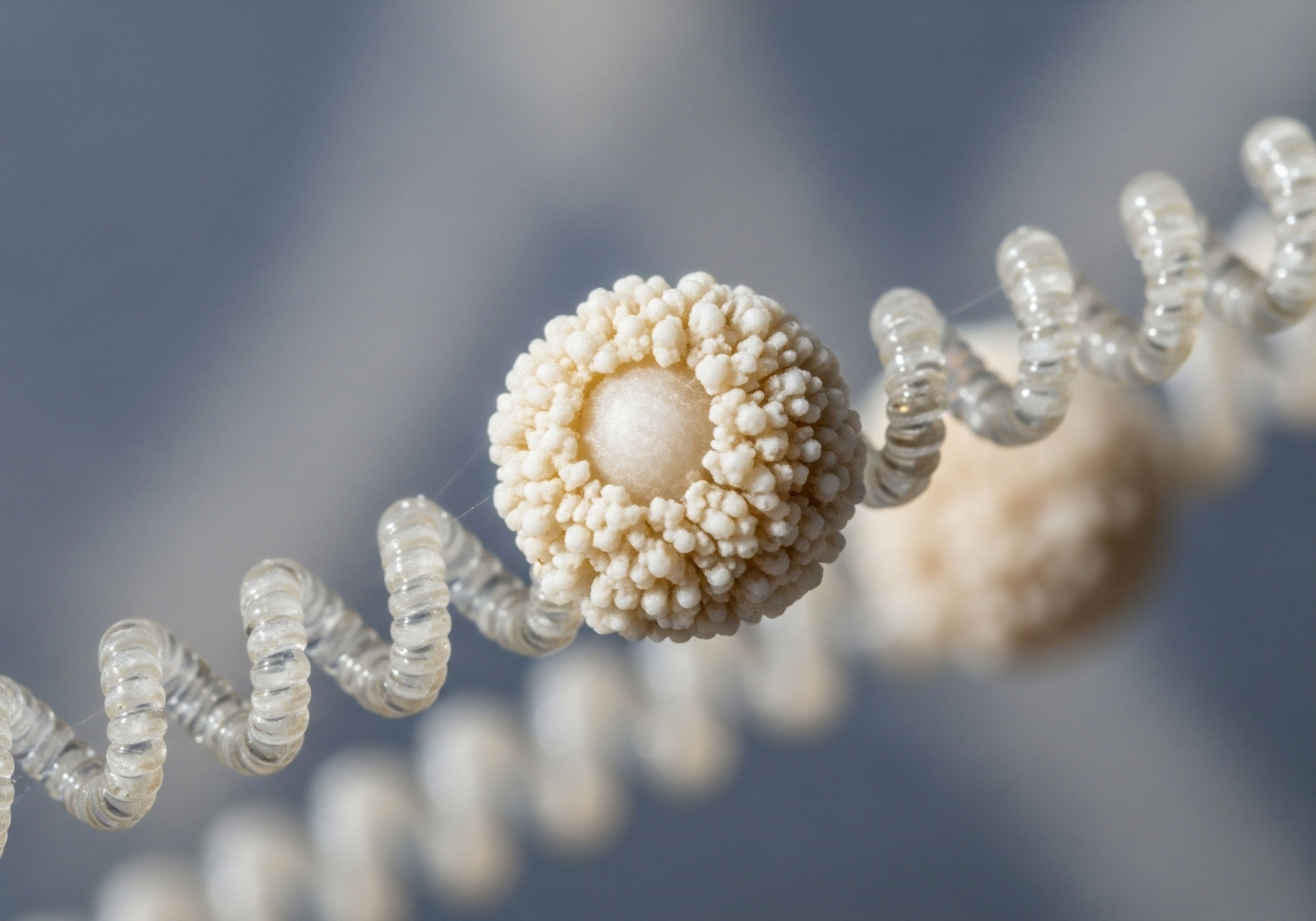

At the molecular level, chronic exposure to elevated glucocorticoids, primarily cortisol, initiates a suppressive cascade that targets multiple levels of the HPG axis. Glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) are expressed in various neuronal populations within the hypothalamus, including GnRH-releasing neurons themselves and the upstream Kiss1 neurons that are critical drivers of GnRH pulsatility.

The binding of cortisol to these receptors can trigger genomic and non-genomic pathways that collectively inhibit neuronal firing and hormone secretion. This leads to a marked reduction in the amplitude and frequency of GnRH pulses released into the hypophyseal portal system, a fundamental prerequisite for sustained gonadotropin (LH and FSH) secretion from the anterior pituitary.

Furthermore, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), the principal secretagogue of the HPA axis, exerts its own potent inhibitory effects. CRH can act directly on GnRH neurons to suppress their activity and also stimulates the release of pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) derived peptides, including β-endorphin.

These endogenous opioids bind to μ-opioid receptors on GnRH neurons, inducing a state of hyperpolarization and rendering them less responsive to excitatory stimuli. The discovery of Gonadotropin-Inhibitory Hormone (RFRP-3 in mammals) adds another layer of complexity. Stress signals have been shown to upregulate the expression of GnIH, which then acts on its receptor, GPR147, located on GnRH neurons, to directly inhibit their function. This creates a redundant, multi-faceted braking system on reproduction.

Lifestyle interventions function as powerful epigenetic modulators, capable of altering the signaling environment that governs hormonal gene expression.

What Is the Interplay between Metabolic Dysfunction and Hormonal Suppression?

Chronic stress and the resultant hypercortisolemia are intimately linked with the development of metabolic syndrome, characterized by insulin resistance, central adiposity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. This metabolic dysfunction serves as a powerful independent and synergistic suppressor of the HPG axis. Increased adiposity, particularly visceral adipose tissue, leads to elevated activity of the aromatase enzyme, which converts testosterone into estradiol.

The resulting increase in circulating estradiol levels in men enhances negative feedback at the level of the hypothalamus and pituitary, further suppressing LH secretion.

Insulin resistance itself is a critical factor. Insulin plays a permissive role in the regulation of gonadal function. In a state of insulin resistance, the complex interplay between metabolic and reproductive hormones is disrupted. Leptin, an adipokine that is typically elevated in obesity, is also implicated.

While acutely leptin can be stimulatory to the HPG axis, a state of chronic hyperleptinemia associated with obesity can lead to leptin resistance in the hypothalamus, diminishing its supportive role for GnRH secretion. Lifestyle interventions, particularly diet and exercise, directly target these metabolic derangements. Weight loss reduces aromatase activity, improves insulin sensitivity, and helps normalize leptin signaling, thereby removing significant sources of HPG axis inhibition.

| Intervention | Primary Molecular/Cellular Target | Physiological Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Sleep Optimization | Downregulation of HPA axis activity; normalization of circadian rhythm; reduced evening glucocorticoid receptor activation. | Restoration of nocturnal LH pulse frequency and amplitude; increased total and free testosterone. |

| Resistance Exercise | Increased androgen receptor density in skeletal muscle; improved insulin sensitivity via GLUT4 translocation; modulation of inflammatory cytokines. | Improved testosterone-to-cortisol ratio; enhanced metabolic control, reducing systemic inflammation. |

| Nutrient-Dense Diet | Provision of essential cofactors (Zinc, Mg) for steroidogenic enzymes (e.g. 3β-HSD, 17β-HSD); reduction of oxidative stress in Leydig cells. | Optimized substrate availability for testosterone synthesis; protection of gonadal tissue from stress-induced damage. |

| Weight Management | Reduction of visceral adipose tissue, leading to decreased aromatase enzyme activity and lower systemic inflammation. | Decreased conversion of testosterone to estradiol; improved negative feedback sensitivity. |

When Are Lifestyle Interventions Insufficient?

While lifestyle modifications are the foundational and often sufficient treatment for functional hypogonadism, there are circumstances where they may not fully restore eugonadal status. The duration and severity of the stressor and the resultant allostatic load can create a deeply entrenched state of suppression.

In some individuals, the degree of metabolic damage or the persistence of an unavoidable stressor (e.g. chronic pain, certain occupations) may limit the efficacy of these interventions alone. Furthermore, a prolonged state of hypogonadism can itself create a barrier to implementing lifestyle changes due to symptoms like severe fatigue, low motivation, and depressive mood.

In such cases, a carefully considered clinical approach may be warranted as an adjunct to ongoing lifestyle efforts. This is where protocols like short-term Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) can be conceptualized. The goal of such a protocol would be to restore physiological testosterone levels to improve energy, mood, and body composition, thereby enabling the patient to more effectively engage in the necessary exercise and dietary changes.

This therapeutic trial can help break the cycle of fatigue and inaction. Other interventions, such as the use of Enclomiphene or Gonadorelin, may be considered to directly stimulate the HPG axis at the pituitary or hypothalamic level, supporting the body’s endogenous production. The decision to introduce pharmacological support requires careful clinical evaluation to confirm the functional nature of the hypogonadism and to ensure it complements, rather than replaces, the essential foundation of lifestyle optimization.

References

- Corona, G. et al. “The role of diet and weight loss in improving secondary hypogonadism in men with obesity with or without type 2 diabetes mellitus.” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 11, 2020, p. 3415.

- Whirledge, S. and Cidlowski, J. A. “Glucocorticoids, stress, and fertility.” Minerva endocrinologica, vol. 35, no. 2, 2010, pp. 109 ∞ 25.

- Leproult, R. and Van Cauter, E. “Effect of 1 week of sleep restriction on testosterone levels in young healthy men.” JAMA, vol. 305, no. 21, 2011, pp. 2173-4.

- Penev, P. D. “The impact of sleep and sleep disorders on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and gonadal systems in men.” Sleep Medicine Clinics, vol. 2, no. 2, 2007, pp. 195-207.

- Kirby, E. K. et al. “Stress increases gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone and decreases reproductive behavior in male rats.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 106, no. 27, 2009, pp. 11324-11329.

- Pilz, S. et al. “Effect of vitamin D supplementation on testosterone levels in men.” Hormone and Metabolic Research, vol. 43, no. 3, 2011, pp. 223-225.

- Hackney, A. C. “Exercise as a stressor and its effects on the male reproductive system.” Journal of Men’s Health, vol. 5, no. 2, 2008, pp. 137-143.

- Zamir, A. et al. “The role of diet and exercise in the management of male hypogonadism.” Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, vol. 22, no. 4, 2021, pp. 1093-1105.

- Kicman, A. T. “Biochemical and physiological aspects of endogenous androgens.” Annals of Clinical Biochemistry, vol. 45, no. 3, 2008, pp. 228-257.

- Bhasin, S. et al. “Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes ∞ an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 103, no. 5, 2018, pp. 1715-1744.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the biological territory you are navigating. It illustrates the intricate communication network within your body and shows how deliberately and profoundly it responds to the signals you provide. The capacity for reversal lies within these very pathways.

The fatigue, the mental fog, the diminished drive ∞ these are not permanent states of being. They are the physiological echoes of a system under duress. By understanding the mechanisms, you have moved from a position of experiencing symptoms to one of wielding knowledge.

Consider the inputs of your own life. Where are the sources of the chronic alarm signal? How can you begin to systematically dismantle them? This process is a dialogue with your own biology. Each well-slept night, each nutrient-dense meal, and each session of purposeful movement is a message of safety sent to your nervous system.

The path to restoring your vitality is built upon these consistent, conscious choices. The journey is personal, and the ultimate potential for recalibration rests within the systems you have now come to understand.