Fundamentals

You feel it as a subtle shift, a sense of disquiet that is difficult to name. Perhaps sleep is less restorative, anxiety hums at a low frequency, or your internal rhythm feels disrupted. This experience, this lived reality of feeling “off,” is a valid and important signal from your body.

It is often within this space of quiet unease that we can begin to understand the profound influence of our internal biochemistry, particularly the role of progesterone. This hormone is a key stabilizing force within the female body, a biological anchor that promotes calm, regulates cycles, and prepares the body for pregnancy. Its presence brings a sense of equilibrium, and its decline or inefficient use can be felt systemically.

The question of whether your daily choices can alter the effectiveness of this crucial hormone is a pivotal one. The answer is an unequivocal yes. Your lifestyle, specifically your dietary patterns and your experience of stress, directly architects your hormonal environment. These are not passive influences; they are active participants in the synthesis, signaling, and metabolism of progesterone.

Understanding this connection is the first step toward reclaiming a sense of biological balance and well-being. It moves the conversation from one of passive suffering to one of active, informed self-stewardship.

The Stress Connection

Your body is equipped with a sophisticated and ancient command center for managing threats, known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. When you perceive a stressor, whether it is a looming work deadline or an internal inflammatory process, this system initiates a cascade of hormonal responses designed for short-term survival.

The primary actor in this response is cortisol. In an ideal scenario, the stressor passes, and the system returns to a state of balance. In our modern world, however, stress is often chronic. This sustained activation of the HPA axis creates a state of continuous high alert.

This persistent state of emergency sends powerful signals throughout the body that deprioritize long-term functions like reproduction and repair. The systems that regulate your reproductive cycle, which are responsible for producing progesterone, receive messages that it is not a safe time to procreate.

This results in a down-regulation of the entire reproductive hormonal cascade, leading to lower progesterone output. It is a biological strategy of resource allocation, where immediate survival is prioritized over the possibility of future conception. This is how chronic stress can manifest as tangible symptoms like irregular cycles, heightened PMS, and feelings of anxiety, all linked to the diminished effectiveness of progesterone.

Chronic stress activates a survival state that directly suppresses the body’s capacity to produce and utilize progesterone effectively.

The Dietary Connection

Hormones are not created from thin air. They are synthesized from raw materials that you must provide through your diet. Progesterone, like all steroid hormones, begins its life as cholesterol. This means that adequate intake of healthy fats is a non-negotiable prerequisite for healthy hormone production.

Your body also requires a suite of specific micronutrients, or cofactors, to facilitate the complex enzymatic reactions that convert cholesterol into progesterone and other essential hormones. These cofactors act like keys that unlock each step of the hormonal assembly line.

A diet lacking in these essential building blocks can create significant bottlenecks in hormone production. Imagine a factory with an abundance of raw materials but a shortage of skilled workers or essential tools; production will inevitably slow down or halt.

Similarly, a body supplied with calories but deficient in key vitamins and minerals will struggle to synthesize adequate levels of progesterone. This is why a nutrient-dense diet, rich in whole foods, is a foundational pillar of hormonal health. It directly supplies the biological resources your body needs to maintain equilibrium and function optimally.

The table below outlines some of the essential nutritional building blocks required for healthy progesterone synthesis and function.

| Nutritional Component | Role in Progesterone Health | Common Food Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy Fats & Cholesterol | Serves as the fundamental precursor for all steroid hormones, including progesterone. | Avocado, olive oil, nuts, seeds, responsibly-sourced animal products. |

| Vitamin C | Has been shown to support corpus luteum function and increase progesterone levels. | Citrus fruits, bell peppers, broccoli, strawberries, kiwi. |

| Magnesium | Acts as a calming mineral that supports the nervous system and is involved in HPA axis regulation. It is a cofactor in hundreds of enzymatic reactions. | Leafy green vegetables, almonds, dark chocolate, pumpkin seeds, black beans. |

| Zinc | Plays a role in the pituitary gland’s release of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which supports ovulation and subsequent progesterone production. | Oysters, beef, pumpkin seeds, lentils, chickpeas. |

| B Vitamins (especially B6) | Essential for liver detoxification of hormones and helps the body produce steroid hormones. Vitamin B6 specifically has been linked to supporting progesterone levels. | Tuna, salmon, chickpeas, poultry, potatoes, bananas. |

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding that diet and stress impact progesterone, we can explore the precise biological mechanisms that govern this relationship. The conversation in wellness circles often includes a concept known as the “pregnenolone steal,” which proposes that under chronic stress, the precursor molecule pregnenolone is diverted away from producing sex hormones to instead manufacture cortisol.

This model provides a simple and compelling narrative. A more precise and clinically accurate understanding, however, reveals a more sophisticated system of communication and resource management within the endocrine system.

Beyond a Simple Steal the Truth about Stress and Progesterone

The “pregnenolone steal” hypothesis suggests a competition for a single pool of pregnenolone. While intuitively appealing, this model is an oversimplification of steroid hormone biochemistry. Steroidogenesis occurs in different cellular compartments and glands, each with its own regulatory controls.

The adrenal glands, which produce cortisol, and the ovaries, which produce the majority of progesterone in a cycling woman, operate under different signaling commands. There is no known mechanism for the adrenal glands to “steal” precursors from the ovaries. The true mechanism is more about top-down signaling than a battle for raw materials.

The more accurate explanation lies in the direct communication, or crosstalk, between the HPA axis (stress) and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis (reproduction). When the brain perceives chronic stress, the hypothalamus releases Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH). This CRH, along with the high levels of cortisol produced by the HPA axis, acts as a powerful inhibitory signal directly on the hypothalamus.

It suppresses the release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), the master signaling hormone of the reproductive system. A suppressed GnRH pulse leads to reduced secretion of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) from the pituitary. Since a mid-cycle LH surge is what triggers ovulation and the subsequent formation of the progesterone-producing corpus luteum, this entire cascade is compromised.

The result is poor ovulation or anovulation, leading to low progesterone production. This is a central nervous system-mediated suppression, a deliberate and strategic down-regulation of the reproductive axis in response to perceived environmental danger.

The influence of stress on progesterone is a centrally-mediated suppression of the reproductive axis, not a peripheral competition for hormonal precursors.

The following table contrasts the simplified “steal” model with the more accurate HPA-HPG crosstalk model.

| Aspect | “Pregnenolone Steal” Hypothesis | HPA-HPG Axis Crosstalk Model |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Competition for a common precursor molecule (pregnenolone) between cortisol and sex hormone pathways. | Inhibitory signaling from the activated stress axis (HPA) to the reproductive axis (HPG) at the level of the brain. |

| Location of Action | Assumes a single, shared pool of precursors, primarily within the adrenal glands. | Occurs in the hypothalamus, where CRH and cortisol suppress GnRH release, affecting downstream pituitary and ovarian function. |

| Key Hormonal Driver | Increased demand for cortisol “steals” pregnenolone. | Elevated CRH and cortisol actively suppress GnRH, LH, and FSH signals. |

| Clinical Implication | Suggests that simply supplementing with pregnenolone could fix the issue. | Highlights the need to address the root cause of HPA axis activation (the stressor) to restore HPG axis function. |

The Brain Connection Allopregnanolone and GABA

The effectiveness of progesterone extends far beyond its role in the uterus. Many of its most profound effects on mood, sleep, and anxiety are mediated by its conversion into a powerful neurosteroid metabolite called allopregnanolone. This conversion happens both in the brain and peripherally.

Allopregnanolone is a potent positive allosteric modulator of the GABA-A receptor, the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter system in the brain. When allopregnanolone binds to the GABA-A receptor, it enhances the calming effect of GABA, essentially helping to turn down the volume on neuronal excitability. This is the biochemical basis for progesterone’s anxiolytic and sedative properties.

Lifestyle factors can significantly disrupt this calming pathway. Chronic stress and the associated inflammation can impair the function of the enzymes responsible for converting progesterone into allopregnanolone. This means that even if circulating progesterone levels are adequate, you may not be getting the full benefit of its neuroprotective effects if the conversion is blocked.

Furthermore, an unhealthy diet, particularly one high in processed foods and sugar, can fuel gut dysbiosis and systemic inflammation, further hindering this critical metabolic process. Supporting this pathway requires managing stress and consuming a diet that provides the necessary cofactors and minimizes inflammation.

How Does Diet Influence Progesterone Receptors?

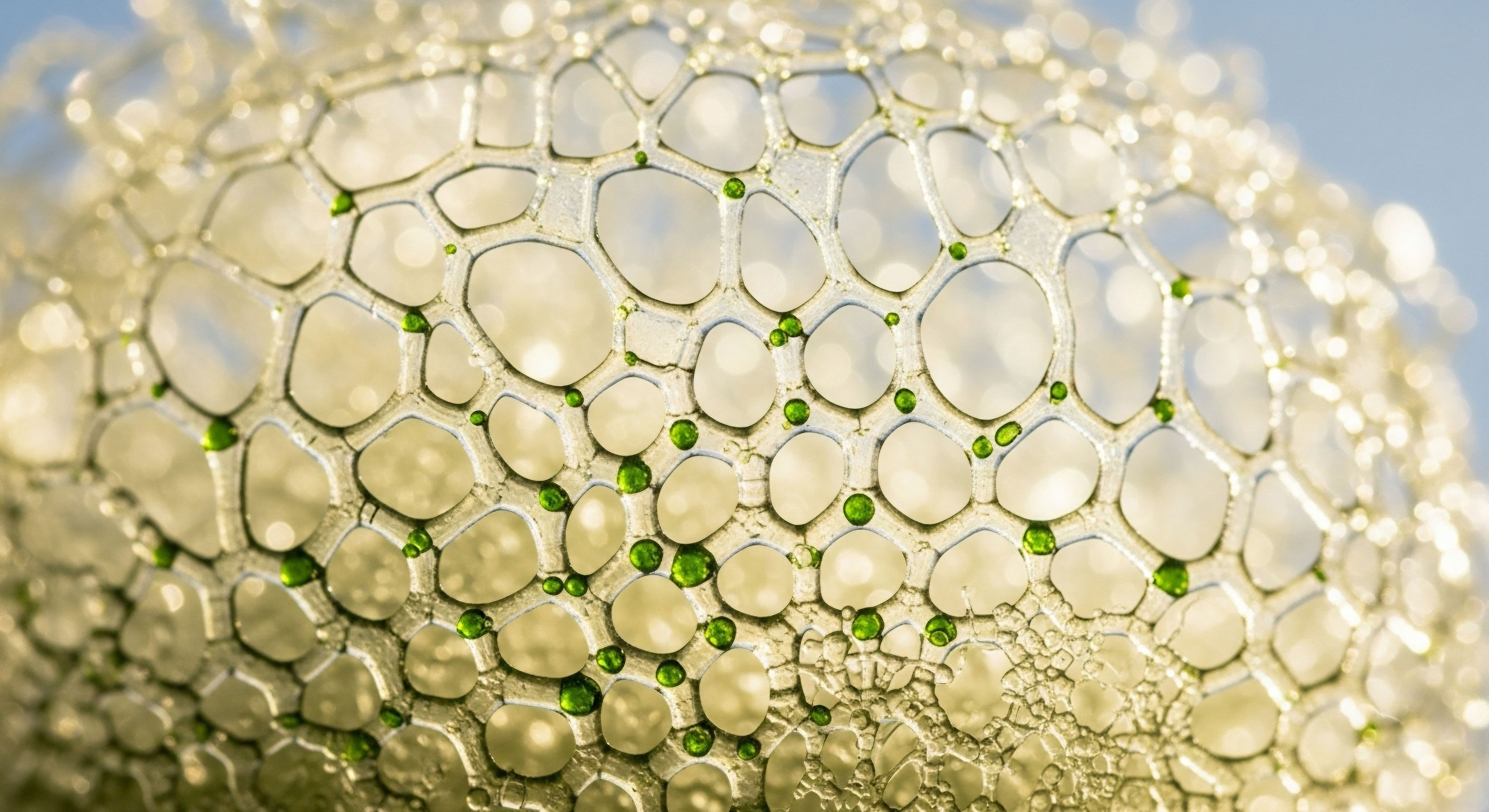

The body’s ability to use progesterone effectively depends not only on its production but also on the health and sensitivity of its receptors. Progesterone receptors are proteins located on cells throughout the body, from the uterine lining to the brain and bones. When progesterone binds to these receptors, it initiates a specific cellular response. The number and sensitivity of these receptors can be influenced by various factors, including diet and inflammation.

Chronic inflammation, often driven by a diet high in refined sugars, processed oils, and low in anti-inflammatory nutrients, can decrease the sensitivity of progesterone receptors. This phenomenon, similar to insulin resistance, means that even with sufficient progesterone in the bloodstream, the cells are less able to “hear” its signal.

A diet rich in phytonutrients, antioxidants, and healthy fats helps to quell inflammation and supports healthy cell membranes, which is crucial for optimal receptor function. Therefore, dietary choices impact both the supply of progesterone and the body’s ability to respond to it, highlighting the deeply interconnected nature of nutrition and endocrine function.

- Support GABA Function ∞ Lifestyle practices that support the GABA system can enhance the calming effects of progesterone and allopregnanolone. This includes mindfulness, meditation, and yoga, which have been shown to increase GABA levels.

- Optimize Magnesium Intake ∞ Magnesium is not only a cofactor for progesterone synthesis but also binds to and modulates GABA receptors, contributing to its relaxing effects.

- Prioritize Sleep ∞ The brain’s glymphatic system, which clears metabolic waste, is most active during deep sleep. Quality sleep is essential for reducing neuroinflammation and supporting healthy neurotransmitter balance.

- Reduce Excitotoxins ∞ Limiting dietary excitotoxins like MSG and excessive caffeine can help prevent over-stimulation of the nervous system, allowing the calming effects of the GABA system to be more pronounced.

Academic

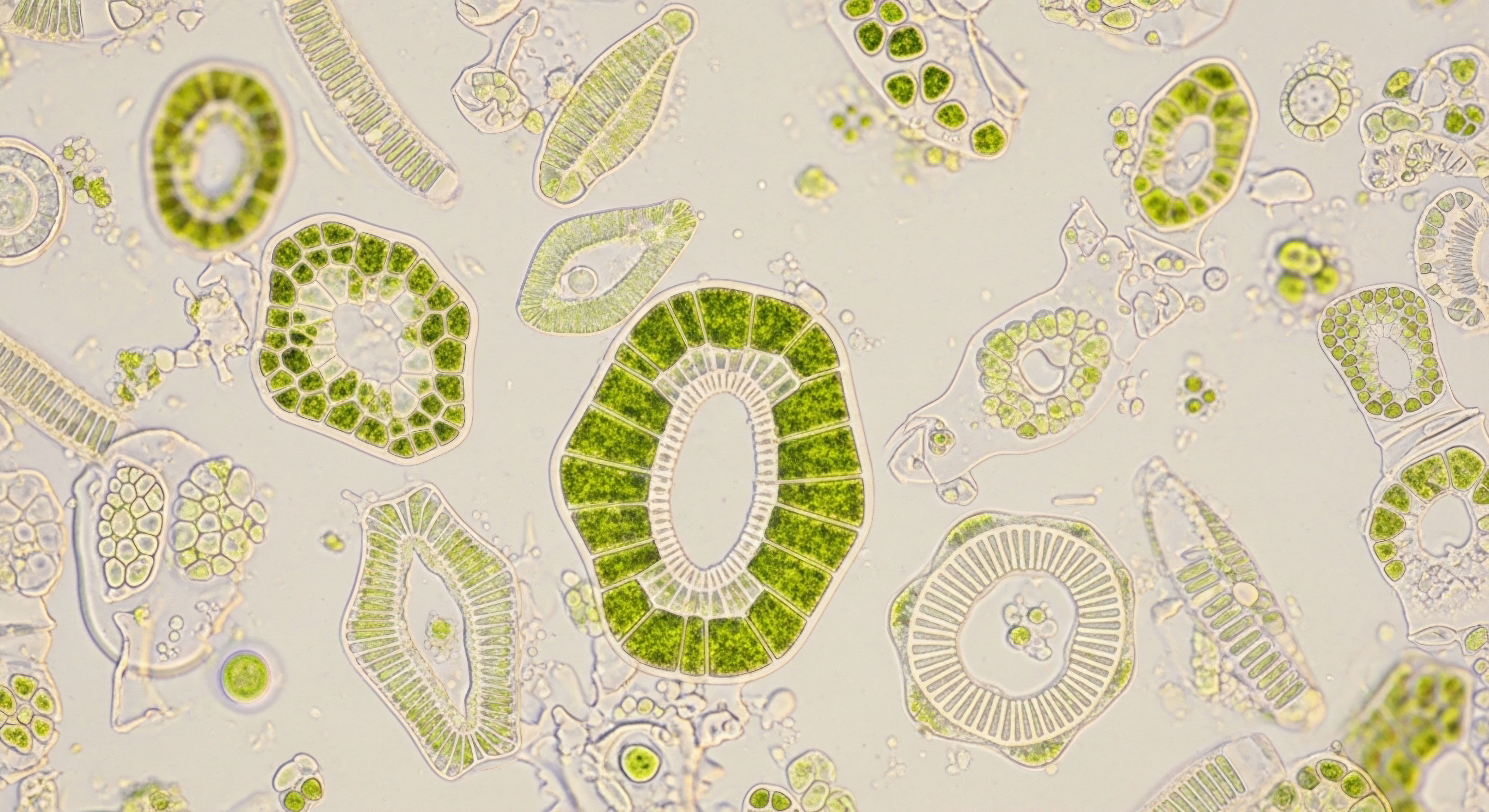

A comprehensive examination of how lifestyle factors modulate progesterone’s effectiveness requires a systems-biology perspective, integrating endocrinology with gastroenterology and neurobiology. While the HPA-HPG axis crosstalk provides a robust model for the effects of stress, an emerging and profoundly important area of research is the role of the gut microbiome.

The complex ecosystem of microorganisms residing in the gastrointestinal tract is now understood to be an active endocrine organ, one that directly engages in steroid hormone metabolism and signaling, thereby creating a powerful gut-hormone axis.

The Gut-Hormone Axis a New Frontier

The human gut microbiota possesses a vast enzymatic capacity that far exceeds that of the host. This collective genome, the microbiome, includes genes that can perform a wide array of chemical transformations on endogenous and exogenous compounds, including steroid hormones. A specific subset of gut bacteria, sometimes referred to as the “estrobolome,” is known to metabolize estrogens.

More recent research illuminates that a similar process occurs with progesterone. The gut microbiota can directly metabolize progesterone, influencing its bioavailability, the profile of its metabolites, and its enterohepatic circulation. This means that the composition and health of your gut microbiome can significantly dictate the systemic impact of progesterone, whether it is produced endogenously or administered therapeutically.

This bidirectional communication pathway also means that progesterone itself can modulate the composition of the gut microbiome. Studies have shown that progesterone can influence the abundance of certain bacterial species and may impact intestinal barrier function.

For instance, some research suggests progesterone can enhance intestinal integrity by increasing the expression of tight-junction proteins, which could reduce the translocation of inflammatory molecules like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) into circulation. This creates a complex feedback loop where gut health influences progesterone, and progesterone, in turn, influences gut health.

What Is Microbial Biotransformation of Progesterone?

When progesterone enters the gut, either through oral administration or via enterohepatic circulation, it is exposed to the metabolic machinery of the resident microbiota. Gut bacteria can perform various biotransformations, primarily through reductive reactions. For example, research has demonstrated that gut microbes can convert progesterone into metabolites like 5α-pregnanolone and 5β-pregnanolone.

These metabolites have their own distinct biological activities. Allopregnanolone (a stereoisomer of pregnanolone) is a potent neurosteroid that modulates GABA-A receptors, as previously discussed. The ability of the gut microbiome to generate these neuroactive steroids directly from progesterone suggests a powerful link between gut microbial composition and neurological and psychological states, such as anxiety and mood disorders, which are often sensitive to progesterone fluctuations.

The clinical implications of this are significant. Inter-individual variability in gut microbiome composition could explain some of the differences in patient responses to oral progesterone therapy. A person with a microbiome rich in bacteria that efficiently metabolize progesterone into its neuroactive derivatives might experience more pronounced calming effects.

Conversely, a dysbiotic microbiome might lead to less effective conversion or the production of other, less beneficial metabolites. Research has identified specific bacteria, such as those from the families Enterobacteriaceae and Veillonellaceae, as key players in the production of pregnanolone from progesterone, and their abundance has been correlated with pregnancy outcomes.

The gut microbiome functions as a distinct endocrine organ, actively metabolizing progesterone and generating neuroactive steroids that influence systemic well-being.

Inflammatory Cascades and Steroidogenic Inhibition

An unhealthy lifestyle, characterized by a pro-inflammatory diet and chronic stress, often culminates in gut dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability. When the intestinal barrier is compromised (“leaky gut”), bacterial components like LPS can enter systemic circulation. LPS is a potent endotoxin that triggers a strong inflammatory response from the host’s immune system. This systemic inflammation has direct and detrimental effects on progesterone production and signaling.

The inflammatory cytokines produced in response to LPS, such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6), can directly suppress ovarian function. They have been shown to inhibit steroidogenesis in granulosa cells of the ovaries, impairing the production of progesterone at its source.

This inflammatory state also exacerbates HPA axis dysfunction, creating a vicious cycle where gut-derived inflammation drives stress signaling, and stress signaling further degrades gut health. This complex interplay illustrates that the effectiveness of progesterone is deeply tied to the body’s overall inflammatory status, which is heavily influenced by diet, stress, and the integrity of the gut-hormone axis.

The table below details some of the key microbial players and their known functions related to progesterone.

| Bacterial Family / Species | Metabolic Action on Progesterone | Potential Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Enterobacteriaceae & Veillonellaceae | Identified as crucial producers of pregnanolone from progesterone. | Their abundance may influence the bioavailability of progesterone and the production of neuroactive metabolites, potentially impacting mood and pregnancy outcomes. |

| Clostridium innocuum | Metabolizes progesterone into epipregnanolone, a neurosteroid with significantly reduced progestogenic activity. | High levels of this bacterium could potentially reduce the therapeutic effectiveness of progesterone by shunting it towards a less active metabolic pathway. |

| Eggerthella lenta | Possesses 21-dehydroxylase activity, which can create progesterone metabolites like allopregnanolone from steroid precursors in bile. | This bacterium can contribute to the pool of neuroactive steroids, linking bile acid metabolism directly to GABAergic tone in the central nervous system. |

| Butyrate Producers (e.g. Faecalibacterium) | Produce butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid. In-vitro studies suggest butyrate may increase progesterone production. | A diet rich in fiber that feeds these bacteria could support endogenous progesterone synthesis through the production of beneficial microbial metabolites. |

- LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) ∞ A marker of endotoxemia and leaky gut. Elevated levels indicate a breach in the intestinal barrier and are associated with systemic inflammation that can suppress ovarian function.

- Zonulin ∞ A protein that modulates the permeability of tight junctions between cells of the wall of the digestive tract. Elevated levels are a direct marker of increased intestinal permeability.

- Beta-glucuronidase ∞ An enzyme produced by some gut bacteria that can deconjugate hormones in the gut, allowing them to be reabsorbed. High levels can contribute to hormonal imbalances by increasing the recirculation of hormones that were meant to be excreted.

- Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) ∞ Metabolites like butyrate, propionate, and acetate produced by beneficial bacteria from dietary fiber. They are crucial for gut health, reducing inflammation, and may influence hormone production.

References

- Solano, Maria Emilia, and Petra Clara Arck. “‘Pregnenolone Steal’ or How High Stress Perception May Drive the Depletion of Progesterone.” Steroids, Pregnancy and Fetal Development, 2020.

- “Tired, Stressed & Gaining Weight ∞ The Truth About Low Progesterone + Progestins | MMP Ep. 185.” YouTube, uploaded by Vitality OET, 10 April 2025.

- Nielsen, S. E. et al. “Stress-induced increases in progesterone and cortisol in naturally cycling women.” Neuropsychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 41, no. 8, 2016, pp. 2155-64.

- Schiller, C. E. et al. “Progesterone and Its Metabolites Play a Beneficial Role in Affect Regulation in the Female Brain.” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 12, no. 7, 2023, p. 2617.

- Yoo, J. Y. “Progestogens Are Metabolized by the Gut Microbiota ∞ Implications for Colonic Drug Delivery.” Pharmaceutics, vol. 12, no. 8, 2020, p. 764.

- Brandon-Mong, Guo-Jie, et al. “Multi-Omics Mapping of Gut Microbiota’s Role in Progesterone Metabolism.” bioRxiv, 2023.

- Kalantaridou, S. N. et al. “Stress and the female reproductive system.” Journal of Reproductive Immunology, vol. 62, no. 1-2, 2004, pp. 61-8.

- ZRT Laboratory. “Re-assessing the Notion of ‘Pregnenolone Steal’.” ZRT Laboratory Blog, 21 June 2017.

- Reddy, D. S. “Neurosteroids and GABA-A Receptor Function.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 1, 2010, p. 1.

- Backstrom, T. et al. “Tolerance to allopregnanolone with focus on the GABA-A receptor.” British Journal of Pharmacology, vol. 162, no. 2, 2011, pp. 327-38.

Reflection

You have now traveled through the intricate biological landscape that connects your daily life to your internal hormonal symphony. You have seen how the perception of stress can reshape your neuroendocrine architecture and how the contents of your plate provide the very building blocks for your body’s most powerful chemical messengers.

This knowledge is more than a collection of facts; it is a lens through which to view your own health journey. It validates the experiences of your body and illuminates the pathways that lead toward balance.

Consider the systems within you not as separate and siloed but as a deeply interconnected network. Your brain, your gut, and your reproductive organs are in constant conversation. What thoughts arise when you view your symptoms as signals within this conversation? This understanding is the starting point. It is the foundation upon which a personalized strategy for wellness can be built, a path that honors your unique physiology and empowers you to become an active participant in your own vitality.

Glossary

cortisol

hpa axis

chronic stress

steroid hormones

pregnenolone steal

pregnenolone

steroidogenesis

progesterone production

allopregnanolone

gaba-a receptor

systemic inflammation

gut dysbiosis

gut microbiome

hpg axis

gut-hormone axis

estrobolome