Fundamentals

You feel it long before you can name it. It is the peculiar exhaustion that settles deep in your bones, the racing mind in the quiet hours of the night, and the sense that your body’s internal rhythm is playing a song you no longer recognize.

The struggle with sleep is a deeply personal, often isolating experience. When you seek help, you are introduced to sleep therapies, structured protocols designed to retrain your brain and body. Yet, a persistent question often remains ∞ why does a therapy work wonders for one person, yet barely make a difference for another?

The answer resides in the foundational biology of your body, in the intricate and constant conversation between your hormones, your metabolism, and your nervous system. Lifestyle factors, specifically your diet and your physical activity, are the primary dialects in this conversation. They are the tools that prepare the physiological terrain, making it either receptive or resistant to the therapeutic process.

Sleep is an active, vital biological process. It is your body’s most critical period of repair, consolidation, and recalibration. During these hours, your endocrine system, the governing body of your hormones, performs a delicate and essential ballet. The success of any sleep therapy is fundamentally linked to how well this internal environment is functioning.

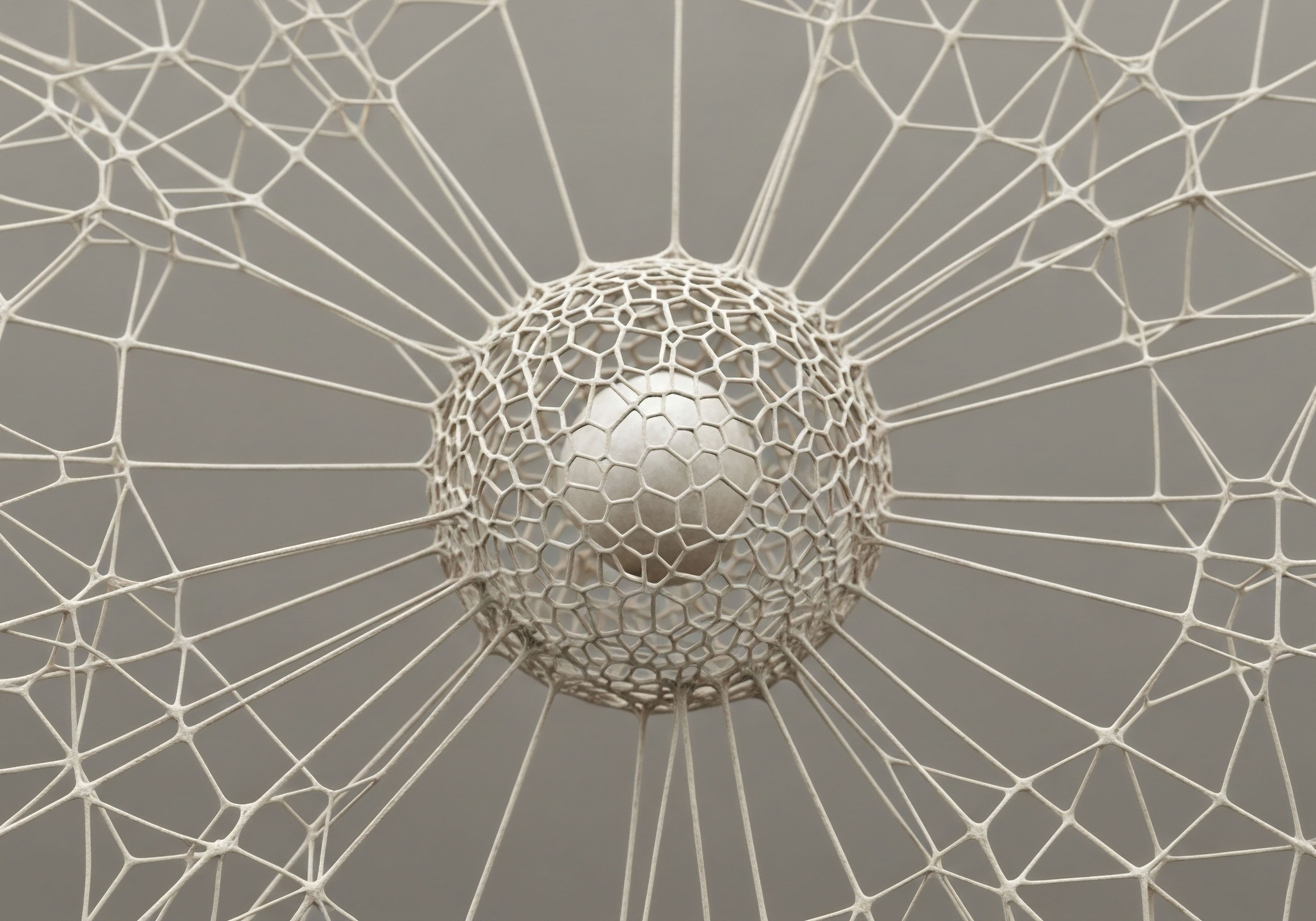

Consider your body as an intricate ecosystem. A sleep therapy, like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I), provides a brilliant blueprint for restoring order. It teaches you behavioral and cognitive strategies to calm the mind and reinforce healthy sleep patterns. The diet you consume and the exercise you perform are the quality of the soil, water, and sunlight available to that ecosystem. Without the right foundational support, even the most perfect blueprint can fail to produce a flourishing garden.

This exploration begins with a validation of your experience. The frustration of trying a recommended therapy without success is not a personal failing. It is a biological signal. It is an indication that the underlying systems that govern sleep may require a different kind of support before a behavioral therapy can take root.

Understanding these systems is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality. We will explore the key hormonal players in the sleep-wake cycle and how your daily choices in food and movement directly influence their function, setting the stage for therapeutic success.

The Hormonal Orchestra of Sleep

At the heart of your sleep-wake cycle is a dynamic interplay of hormones, each with a specific role and rhythm. Think of it as an orchestra, where each instrument must play in time and at the correct volume for the symphony of a restful night to occur. The two lead players in this orchestra are cortisol and melatonin.

Cortisol, often called the “stress hormone,” is more accurately described as the hormone of alertness and arousal. Its production is governed by a system known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. A healthy cortisol rhythm involves a sharp peak within 30 minutes of waking in the morning, which provides the energy and focus to start your day.

Throughout the day, these levels should gradually decline, reaching their lowest point in the evening to allow for sleep. In states of chronic stress or metabolic dysfunction, this rhythm becomes disrupted. Cortisol may be too low in the morning, leading to fatigue, or it may fail to decrease at night, creating a state of “tired but wired” hyperarousal that makes falling asleep feel impossible.

Melatonin is the counterpoint to cortisol. It is the hormone of darkness, signaling to your body that it is time to prepare for sleep. Its release is triggered by the absence of light and is suppressed by light exposure.

Melatonin does not force you to sleep; rather, it opens the gate to sleep by quieting the alerting signals in your brain. A healthy sleep-wake cycle depends on a robust melatonin surge in the evening as cortisol levels reach their nadir. When cortisol remains elevated at night, it can directly suppress melatonin production, effectively locking the gate to sleep.

How Diet and Exercise Tune the System

Your daily lifestyle choices are the most powerful conductors of this hormonal orchestra. They send constant signals to your HPA axis and metabolic systems, directly influencing the cortisol and melatonin rhythms that are so essential for sleep.

Dietary choices have a profound impact on blood sugar regulation and systemic inflammation, both of which are major inputs to the HPA axis. A diet high in refined carbohydrates and sugars creates a rollercoaster of blood glucose spikes and crashes. These fluctuations are perceived by the body as a stressor, prompting the release of cortisol to stabilize blood sugar.

When this occurs close to bedtime, it can artificially elevate cortisol, disrupting the natural decline needed for sleep onset. A diet centered on whole foods, with adequate protein, healthy fats, and fiber, promotes stable blood glucose and reduces the inflammatory load on the body, thereby calming the HPA axis and supporting a healthy cortisol rhythm.

Exercise acts as a potent regulator of the body’s stress response systems. The timing, intensity, and type of physical activity can be used to strategically shape your cortisol curve. Morning exercise, for instance, can help amplify the natural morning cortisol peak, improving daytime energy and reinforcing a healthy 24-hour rhythm.

Moderate-intensity exercise in the afternoon can help process excess stress hormones and promotes a deeper, more restorative sleep at night. It also increases the body’s sensitivity to insulin, which helps to stabilize blood sugar and further reduces the burden on the HPA axis.

By consciously applying these lifestyle levers, you are creating a biological environment where sleep therapies are not just fighting against a tide of physiological disruption, but are instead supported by a system that is primed and ready for rest.

Intermediate

To truly appreciate how lifestyle factors can amplify the effects of sleep therapies, we must move beyond foundational concepts and examine the specific biological mechanisms at play. Sleep therapies like CBT-I are designed to correct maladaptive behaviors and cognitive patterns that perpetuate insomnia.

They operate on the principle of neuroplasticity, retraining the brain’s response to sleep-related cues. The success of this retraining process is heavily dependent on the underlying neurochemical environment. Diet and exercise are powerful tools for modulating this environment, creating a brain that is more receptive to change and a body that is physiologically capable of sustaining restorative sleep. They are the biochemical support system that allows cognitive and behavioral strategies to achieve their full potential.

The connection lies in the body’s intricate feedback loops. Insomnia is often characterized by a state of hyperarousal, a persistent “on” signal in the nervous system. This state is driven by an overactive HPA axis and an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters. Lifestyle interventions directly target these systems.

A well-formulated diet can provide the essential building blocks for calming neurotransmitters, while targeted exercise can help reset the body’s central stress-response clock. By addressing the physiological roots of hyperarousal, you create a state of permissive calm, allowing the techniques learned in therapy to be implemented more effectively. This section will delve into the specific ways that nutrition and physical activity can be structured to support the neurobiological goals of sleep therapy.

Nutritional Architecture for a Calm Nervous System

The brain’s state of arousal is largely dictated by the balance between two key neurotransmitters ∞ glutamate, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter. In many individuals with insomnia, there is an excess of glutamate activity and a relative deficiency in GABAergic tone, leading to a racing mind, anxiety, and an inability to disengage from wakefulness. Nutritional strategies can directly influence this delicate balance.

A well-structured diet provides the essential precursors for calming neurotransmitters, directly supporting the neurological goals of sleep therapy.

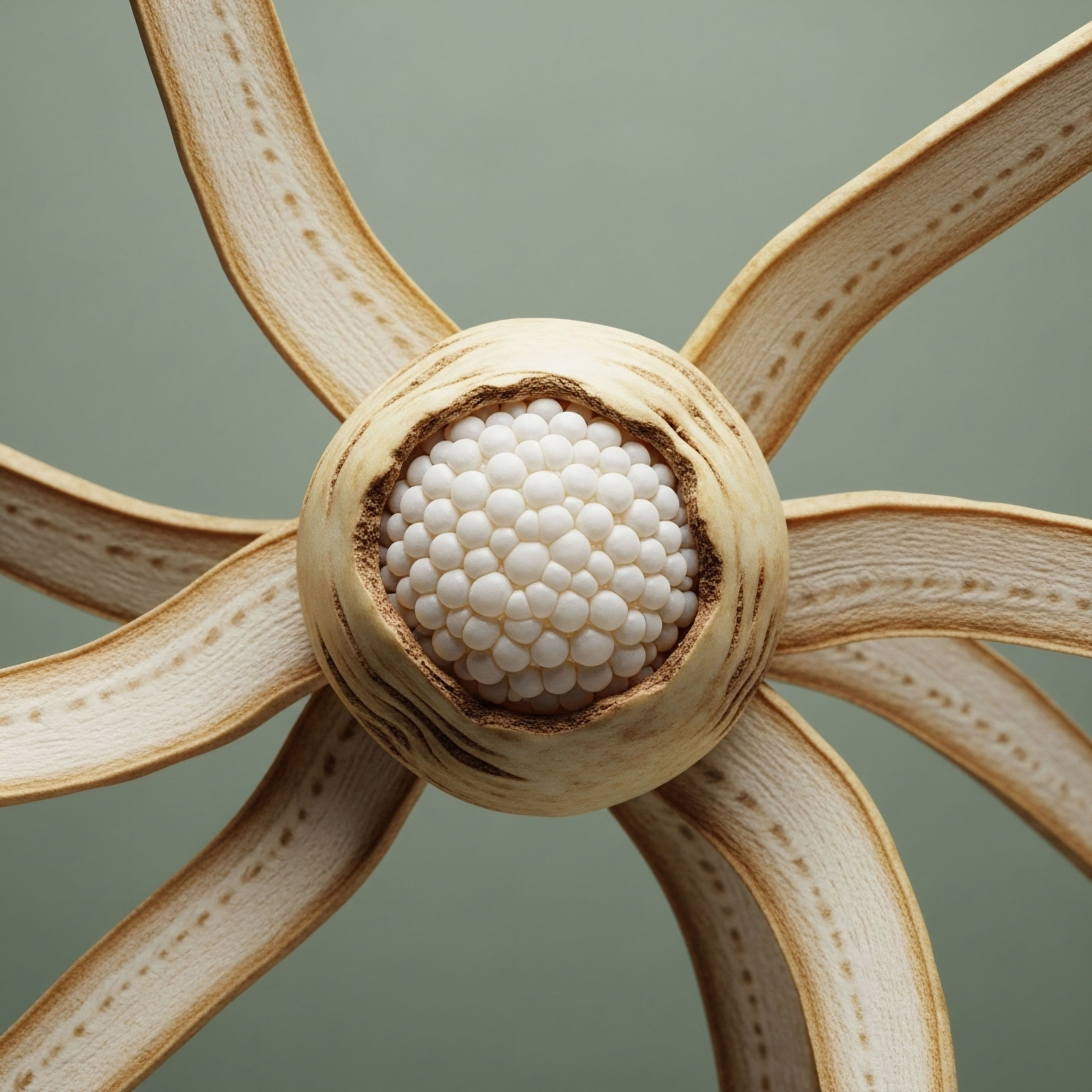

One of the most effective ways to support GABA production is to ensure an adequate intake of its precursors and cofactors. The amino acid glutamine is converted to glutamate, which is then converted to GABA by the enzyme glutamate decarboxylase (GAD). This conversion is dependent on the active form of vitamin B6 (pyridoxal-5-phosphate).

Therefore, a diet rich in vitamin B6 from sources like chickpeas, liver, tuna, and salmon is essential. Magnesium also plays a critical role, as it helps to both increase GABA levels and reduce the activity of the excitatory NMDA receptor, which is stimulated by glutamate. Foods high in magnesium, such as leafy greens, almonds, and avocados, can help promote a more relaxed neurological state.

Furthermore, the stability of your blood glucose has a direct impact on glutamate-GABA balance. Sharp drops in blood sugar, or hypoglycemia, can trigger an excitatory response in the brain, leading to a surge in glutamate and cortisol. This is a common cause of middle-of-the-night awakenings.

A dietary approach that minimizes refined carbohydrates and emphasizes complex carbohydrates, healthy fats, and adequate protein helps to maintain stable blood glucose levels throughout the night. This metabolic stability translates directly into neurochemical stability, preventing the excitatory surges that fragment sleep and undermine the progress made in sleep therapy.

What Is the Role of Gut Health in Sleep Modulation?

The gut microbiome, the vast community of microorganisms residing in your digestive tract, has emerged as a major regulator of the gut-brain axis and, by extension, sleep. Your gut bacteria are capable of producing a wide array of neurotransmitters, including GABA and serotonin, a precursor to melatonin.

A healthy, diverse microbiome can contribute to a systemic pool of these calming neurochemicals. Conversely, a state of dysbiosis, or an imbalance in gut bacteria, can lead to reduced production of these beneficial compounds and an increase in inflammatory molecules that disrupt sleep.

Diet is the single most powerful factor shaping the composition of your gut microbiome. A diet rich in prebiotic fibers from sources like onions, garlic, asparagus, and bananas provides the necessary fuel for beneficial bacteria to thrive. Fermented foods, such as yogurt, kefir, and sauerkraut, introduce probiotic bacteria directly into the system.

By cultivating a healthy gut ecosystem, you are essentially creating a peripheral factory for the very neurotransmitters that sleep therapies aim to balance centrally in the brain. This creates a powerful synergistic effect, where therapeutic progress is supported by a body that is biochemically primed for rest.

Exercise Protocols for Hormonal Recalibration

Physical activity is a powerful tool for recalibrating the HPA axis and enhancing the body’s natural circadian rhythms. The key is to apply exercise strategically, using different modalities and timings to achieve specific hormonal and physiological outcomes that support sleep.

Morning Activation for Circadian Alignment

Engaging in moderate-intensity aerobic exercise in the morning, such as a brisk walk, jog, or cycling session, can significantly reinforce the body’s natural cortisol awakening response (CAR). This morning cortisol surge is critical for setting the 24-hour body clock.

A robust morning peak helps to ensure a corresponding steep decline in cortisol levels in the evening, which is a prerequisite for the timely release of melatonin. Morning exercise, particularly when performed outdoors with exposure to natural light, is one of the most effective ways to anchor your circadian rhythm and combat the flat cortisol curve often seen in individuals with insomnia and fatigue.

Afternoon Resistance Training for Stress Decompression

Resistance training, performed in the mid-to-late afternoon, can be particularly beneficial for sleep. This type of exercise acts as a controlled physiological stressor, temporarily increasing cortisol and adrenaline. Following this acute stress, the body’s feedback mechanisms initiate a powerful compensatory relaxation response, leading to a significant drop in cortisol levels several hours later, perfectly timed for the evening.

Additionally, resistance training improves glucose uptake by the muscles, enhancing insulin sensitivity and contributing to the metabolic stability that is so crucial for uninterrupted sleep. This makes it an excellent tool for processing the accumulated stress of the day and preparing the body for deep, restorative rest.

The table below outlines how different exercise timings can be used to support sleep therapy goals.

| Timing | Exercise Type | Primary Biological Mechanism | Therapeutic Synergy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Morning (6-8 AM) | Outdoor Aerobic (Walking, Jogging) | Amplifies Cortisol Awakening Response; Anchors Circadian Rhythm via Light Exposure. | Enhances daytime alertness and reduces sleep-related anxiety by reinforcing a predictable sleep-wake cycle. |

| Afternoon (3-5 PM) | Resistance Training (Weights, Bodyweight) | Creates acute cortisol spike followed by a compensatory drop; Improves insulin sensitivity. | Reduces evening hyperarousal; Prevents blood sugar-related awakenings. |

| Early Evening (6-7 PM) | Restorative (Yoga, Tai Chi) | Downregulates the sympathetic nervous system; Increases parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) tone. | Directly supports relaxation techniques learned in CBT-I by lowering physiological arousal. |

By integrating these targeted lifestyle strategies, you are not merely hoping for a better night’s sleep; you are actively architecting a physiological state that is conducive to it. You are providing the raw materials for neurotransmitter balance, stabilizing the metabolic fluctuations that disrupt sleep, and recalibrating the hormonal rhythms that govern the sleep-wake cycle.

This creates a powerful foundation upon which the cognitive and behavioral skills learned in therapy can be built, transforming the therapeutic process from an uphill battle into a collaborative effort between mind and body.

Academic

The therapeutic efficacy of interventions for chronic insomnia, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT-I), is well-established in clinical literature. These therapies are predicated on restructuring the cognitive and behavioral patterns that perpetuate a state of hyperarousal. The success of such therapies, however, is contingent upon the biological substrate of the patient ∞ the intricate, interconnected network of endocrine, metabolic, and neurological systems.

An exploration into the academic underpinnings of this relationship reveals that lifestyle factors, specifically diet and exercise, function as potent epigenetic and metabolic modulators. They directly influence the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, insulin signaling pathways, and the delicate equilibrium between GABAergic and glutamatergic neurotransmission.

These are the very systems that, when dysregulated, constitute the physiological basis of hyperarousal. Therefore, integrating targeted lifestyle interventions with sleep therapies represents a shift from a purely psychological model to a comprehensive psychoneuroimmunological approach, creating a biological environment permissive to therapeutic change.

This deep analysis will focus on a single, dominant pathway ∞ the feedback loop connecting HPA axis function, cellular insulin sensitivity, and the subsequent impact on sleep architecture. We will examine how dietary composition and exercise physiology directly modify this axis. The central thesis is that chronic insomnia is frequently a clinical manifestation of underlying metabolic and neuroendocrine dysregulation.

Lifestyle interventions are not merely supportive adjuncts; they are primary tools for correcting this dysregulation, thereby increasing the probability of a successful outcome with established sleep therapies. By recalibrating the body’s internal milieu, we create a system that is no longer fighting itself, allowing behavioral and cognitive strategies to engage with a receptive and stable neurobiological platform.

The HPA Axis as the Central Regulator of Arousal

The HPA axis is the body’s primary stress-response system, a finely tuned cascade that begins with the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus, stimulating the pituitary to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn signals the adrenal glands to produce cortisol.

In a healthy individual, this system operates with a distinct circadian rhythmicity, peaking upon waking and troughing in the late evening. In chronic insomnia, this rhythm is frequently disrupted, characterized by elevated nocturnal cortisol levels and a blunted morning response. This persistent elevation of cortisol at night directly promotes wakefulness by inhibiting the sleep-promoting neurons in the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO) and suppressing the nocturnal rise of melatonin.

This state of HPA axis hyperactivity is the physiological signature of hyperarousal. The elevated CRH associated with this state has direct wake-promoting effects on the brain, independent of cortisol. It increases EEG frequency and contributes to the fragmented sleep architecture and frequent awakenings characteristic of insomnia.

Sleep therapies like CBT-I aim to reduce the cognitive anxiety that activates this axis. The efficacy of these therapies can be profoundly enhanced by simultaneously addressing the metabolic factors that also contribute to HPA axis dysregulation.

How Does Insulin Resistance Perpetuate HPA Axis Dysfunction?

Insulin resistance, a condition where cells become less responsive to the effects of insulin, is a key metabolic stressor that fuels HPA axis hyperactivity. A diet high in refined carbohydrates leads to chronic hyperinsulinemia. This state promotes systemic inflammation through pathways like NF-κB.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, are potent activators of the HPA axis, signaling a state of systemic threat that perpetuates CRH and cortisol production. This creates a vicious cycle ∞ sleep deprivation itself has been shown to induce insulin resistance, which in turn drives inflammation and further HPA axis activation, solidifying the state of hyperarousal.

Furthermore, the brain’s own glucose utilization is affected. While the brain is not dependent on insulin for glucose uptake, insulin signaling in the hypothalamus plays a key role in regulating systemic metabolism and HPA axis activity. Insulin resistance in the brain can impair the negative feedback mechanisms that normally suppress cortisol production, leading to a chronically overactive stress response.

This metabolic disruption provides a constant, underlying physiological pressure that can counteract the calming effects of cognitive reframing or relaxation techniques taught in therapy.

Targeted exercise protocols function as a non-pharmacological method for restoring insulin sensitivity and recalibrating HPA axis feedback loops.

Exercise serves as a powerful counter-regulatory intervention. Both aerobic and resistance exercise increase glucose uptake by muscle tissue through insulin-independent pathways (via AMPK activation), reducing the glycemic load and lowering circulating insulin levels. Over time, consistent exercise improves systemic insulin sensitivity, which reduces the inflammatory signaling that drives HPA axis activation.

Physical activity also appears to directly enhance the efficiency of the HPA axis negative feedback loop, allowing the system to return to baseline more quickly after a stressor. This physiological adaptation creates a more resilient and less reactive stress response system, providing a stable foundation for the psychological work of sleep therapy.

Neurotransmitter Balance the Final Common Pathway

The ultimate determinant of sleep onset and maintenance is the neurochemical balance within the brain, specifically the ratio of inhibitory GABA to excitatory glutamate. The dysregulation of the HPA axis and metabolic health has a direct and profound impact on this ratio, tipping the scales toward excitotoxicity and hyperarousal.

The Impact of Metabolic Health on GABA and Glutamate

Chronic cortisol elevation, driven by HPA axis dysfunction, can alter the expression of GABA receptors, reducing their sensitivity and impairing the brain’s primary calming system. Simultaneously, metabolic instability affects the availability of precursors for these neurotransmitters. As previously noted, the conversion of glutamate to GABA is a vitamin B6-dependent process. Systemic inflammation, often a consequence of poor diet and insulin resistance, can deplete B6 levels, thereby impairing GABA synthesis.

A diet that stabilizes blood glucose and is rich in the necessary cofactors can directly support this crucial enzymatic pathway. The inclusion of foods containing compounds like L-theanine (found in green tea) can further support this balance by blocking glutamate receptors and promoting alpha brain wave activity, a state associated with relaxed wakefulness.

This nutritional approach provides the brain with the biochemical tools it needs to achieve the inhibitory state required for sleep, complementing the top-down cognitive control taught in therapies like CBT-I.

The following table details the interplay between lifestyle factors, physiological systems, and their combined effect on sleep therapy efficacy.

| Lifestyle Intervention | Target Physiological System | Mechanism of Action | Impact on Sleep Therapy (e.g. CBT-I) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Glycemic, Nutrient-Dense Diet | Metabolic Health (Insulin Signaling) | Stabilizes blood glucose, reduces hyperinsulinemia, lowers systemic inflammation (IL-6, TNF-α). | Reduces a primary physiological driver of HPA axis activation, preventing nocturnal hypoglycemia-induced awakenings. |

| Consistent Moderate Exercise | HPA Axis Regulation | Improves insulin sensitivity, enhances cortisol negative feedback efficiency, promotes a healthy circadian rhythm. | Lowers baseline physiological arousal, making relaxation and stimulus control techniques more effective. |

| Targeted Nutrient Intake (Mg, B6) | Neurotransmitter Synthesis | Provides essential cofactors for the GAD enzyme, converting glutamate to GABA. Magnesium modulates NMDA receptor activity. | Increases the brain’s inhibitory tone, supporting cognitive reframing by reducing the biological basis of anxious thoughts. |

| Mind-Body Movement (Yoga, Tai Chi) | Autonomic Nervous System | Increases vagal tone and parasympathetic activity, directly counteracting the sympathetic “fight-or-flight” response. | Provides a direct physiological tool for managing the somatic symptoms of anxiety, reinforcing therapeutic goals. |

In conclusion, an academic appraisal reveals that lifestyle factors are not peripheral to the treatment of insomnia; they are central to it. They operate at the intersection of endocrinology, metabolism, and neuroscience, directly influencing the physiological systems that maintain the state of hyperarousal.

A therapeutic approach that integrates dietary strategy and exercise physiology with established psychological therapies like CBT-I addresses the condition from both a top-down (cognitive) and bottom-up (biological) perspective. This integrated model acknowledges that a mind cannot be retrained in isolation from the body it inhabits. By optimizing the biological terrain, we create the necessary conditions for psychological therapies to achieve deep, lasting, and restorative success.

- Hormonal Precursors ∞ A diet lacking in specific amino acids, vitamins, and minerals can directly limit the body’s ability to synthesize key sleep-related neurochemicals and hormones. Tryptophan, for instance, is a critical precursor to serotonin, which is subsequently converted to melatonin. Insufficient dietary intake of tryptophan, found in foods like poultry, nuts, and seeds, can create a bottleneck in this production pathway.

- Micronutrient Cofactors ∞ The enzymatic reactions that govern these conversions are dependent on various micronutrients. The conversion of tryptophan to serotonin requires iron, riboflavin, and vitamin B6. The final step, converting serotonin to melatonin, is also a multi-step process that relies on adequate levels of folate and zinc. Deficiencies in any of these cofactors can impair the entire cascade.

- Systemic Inflammation ∞ A pro-inflammatory diet, typically high in processed foods, sugar, and unhealthy fats, creates a state of low-grade systemic inflammation. Inflammatory cytokines can disrupt the normal functioning of the pineal gland and alter the expression of enzymes involved in melatonin synthesis. This inflammatory state can effectively blunt the body’s natural melatonin surge, even in the presence of adequate darkness cues.

- Thermogenic Effect of Exercise ∞ Physical activity raises the core body temperature. Following exercise, a compensatory drop in body temperature occurs. This post-exercise cooling effect mimics the natural drop in body temperature that occurs in the evening and helps to initiate sleep. Timing moderate exercise in the late afternoon can therefore enhance this natural signal, promoting sleep onset.

- Adenosine Accumulation ∞ During periods of wakefulness and energy expenditure, adenosine accumulates in the brain. Adenosine acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter, promoting sleep drive. Exercise accelerates this accumulation, increasing the homeostatic pressure to sleep. This can lead to deeper, more restorative slow-wave sleep.

- Anxiolytic and Antidepressant Effects ∞ Regular exercise has well-documented effects on mood, mediated through the release of endorphins and the regulation of neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine. By reducing underlying anxiety and depression, which are major contributors to insomnia, exercise helps to remove a significant psychological barrier to restful sleep.

References

- St-Onge, Marie-Pierre, et al. “Fiber and Saturated Fat Are Associated with Sleep Arousals and Slow Wave Sleep.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, vol. 12, no. 1, 2016, pp. 19-24.

- Vitiello, Michael V. and Susan M. McCurry. “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia in Older Adults.” Sleep Medicine Clinics, vol. 4, no. 4, 2009, pp. 565-576.

- Kaliman, Perla, et al. “Rapid changes in histone deacetylases and inflammatory gene expression in expert meditators.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 40, 2014, pp. 96-107.

- Spiegel, Karine, et al. “Sleep loss ∞ a novel risk factor for insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes.” Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 99, no. 5, 2005, pp. 2008-2019.

- Nobre, Anna C. and Glyn W. Humphreys, eds. Episodic memory ∞ new directions in research. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Irwin, Michael R. et al. “Sleep and inflammation ∞ partners in sickness and in health.” Nature reviews immunology, vol. 10, no. 1, 2010, pp. 30-41.

- Buysse, Daniel J. “Insomnia.” JAMA, vol. 309, no. 7, 2013, pp. 706-716.

- Knutson, Kristen L. and Eve Van Cauter. “Associations between sleep loss and increased risk of obesity and diabetes.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1129, no. 1, 2008, pp. 287-304.

- Dattilo, M. et al. “Sleep and muscle recovery ∞ endocrinological and molecular basis for a new and promising hypothesis.” Medical hypotheses, vol. 77, no. 2, 2011, pp. 220-222.

- Besedovsky, Luciana, et al. “Sleep and immune function.” Pflügers Archiv-European Journal of Physiology, vol. 463, no. 1, 2012, pp. 121-137.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Internal Environment

You have now journeyed through the intricate biological landscape that governs your sleep. You have seen how the silent conversation between your hormones, your metabolism, and your nervous system dictates the quality of your rest. This knowledge moves you beyond the frustration of a therapy that did not meet its promise and into a position of profound capability.

The information presented here is a map, showing the interconnected pathways within your own physiology. It reveals that the journey to restorative sleep is one of internal calibration. It is about learning to tune your own biological orchestra through the daily, deliberate choices you make at your dinner plate and with your physical body.

What Signals Are You Sending?

Consider your next meal or your next opportunity for movement. View it not as a task or a chore, but as a direct communication with your internal systems. Are you sending a signal of stability and calm, or one of stress and disruption? This perspective transforms the mundane into the meaningful.

It reframes your lifestyle as the foundational practice that allows for higher-level therapeutic work to succeed. The path forward is one of partnership with your own body, of providing it with the precise inputs it needs to do what it is designed to do ∞ repair, restore, and thrive.

The ultimate goal is to create a state of physiological resilience, an internal environment where sleep is no longer a struggle to be won, but a natural state to which your body effortlessly returns.