Understanding Cellular Responsiveness to Peptides

Many individuals find themselves contemplating the subtle shifts within their physical being, perhaps noticing a recalibration in strength, a change in recovery patterns, or a persistent longing for the vigor that once felt innate. This experience, often dismissed as an inevitable aspect of aging, instead represents a profound invitation to investigate the intricate language spoken by our biological systems.

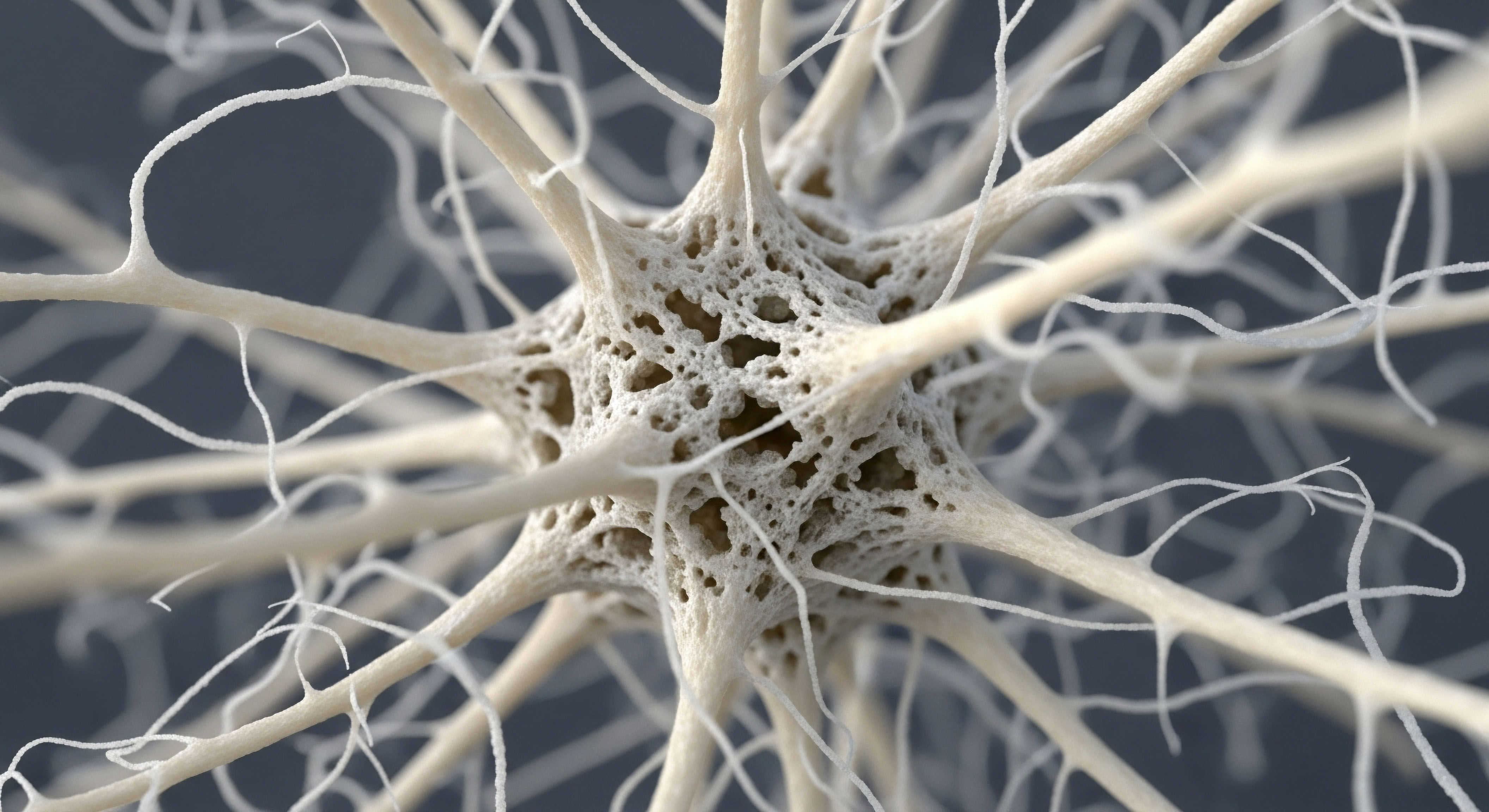

A fundamental understanding of how our bodies respond to specific biochemical messengers, such as peptides, can illuminate a path toward restoring vitality. Peptides, diminutive chains of amino acids, act as cellular emissaries, transmitting instructions that govern a multitude of physiological processes, including those crucial for muscle maintenance and growth.

When considering the augmentation of muscle cells, the discussion frequently turns to various peptides designed to support anabolic pathways. These agents function by interacting with specific receptors on cell surfaces, initiating cascades of intracellular signaling that can lead to enhanced protein synthesis, cellular repair, and metabolic efficiency.

The efficacy of these messengers, however, is not an isolated event; it is profoundly influenced by the environment in which these cellular communications occur. The body’s internal milieu, shaped by daily habits, plays a decisive role in how effectively these peptide signals are received and translated into tangible physiological outcomes.

Peptides serve as vital cellular messengers, orchestrating numerous biological functions, including muscle growth and repair.

The Intrinsic Role of Peptides in Muscle Biology

Muscle cells, known as myocytes, possess an inherent capacity for adaptation and regeneration. This remarkable plasticity allows them to respond to mechanical stimuli, such as resistance exercise, by increasing in size and strength. Peptides facilitate this adaptive response through several key mechanisms.

For instance, growth hormone secretagogues (GHSs), a class of peptides including Ipamorelin and Sermorelin, stimulate the pituitary gland to release endogenous growth hormone (GH). This increase in GH subsequently elevates levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), a potent anabolic hormone, which directly promotes muscle protein synthesis and satellite cell activation. Satellite cells are quiescent stem cells residing within muscle tissue, poised to differentiate and fuse with existing muscle fibers, thereby contributing to muscle repair and hypertrophy.

The intricate dance between these peptides and their target cells highlights a sophisticated biological feedback system. Optimal functioning of this system hinges on the sensitivity of cellular receptors and the efficiency of downstream signaling pathways. A cellular environment characterized by chronic inflammation, nutrient deficiencies, or persistent metabolic dysregulation can diminish this sensitivity, effectively dampening the anabolic signals peptides are designed to deliver.

Thus, understanding the foundational biological context is essential for appreciating how external factors can either impede or potentiate peptide action.

How Lifestyle Choices Optimize Peptide Efficacy

For those familiar with the basic tenets of peptide action, the natural progression involves understanding how to maximize their physiological impact. The question then becomes, how can we intentionally shape our internal landscape to ensure these potent cellular directives are not merely received, but genuinely amplified?

The answer resides in a deliberate and integrated approach to lifestyle, where diet and exercise become more than mere habits; they become strategic levers for biochemical recalibration. This perspective moves beyond simple adherence to a regimen, instead focusing on a synergistic partnership between exogenous peptide support and endogenous physiological optimization.

The interconnectedness of the endocrine system ensures that no single pathway operates in isolation. Lifestyle factors exert a pervasive influence across these systems, creating a foundation upon which peptide therapies can exert their most profound effects. Consider the metabolic demands of muscle tissue ∞ it requires energy, structural components, and precise signaling to grow and repair.

When these requirements are met with precision, the cellular machinery responsible for responding to peptides operates at its zenith, leading to a more robust and sustained anabolic response.

Optimizing peptide efficacy requires a deliberate integration of lifestyle choices that strategically recalibrate biochemical pathways.

Exercise as a Primal Anabolic Signal

Resistance exercise, in particular, functions as a powerful physiological primer for muscle cells. The mechanical tension and metabolic stress induced by lifting weights create a temporary, yet profound, anabolic window. This window is characterized by increased blood flow to muscle tissue, enhanced nutrient delivery, and the upregulation of various growth factors and receptors, including those sensitive to peptides.

Engaging in regular, progressive resistance training programs establishes a continuous cycle of muscle breakdown and repair, maintaining a state of heightened cellular readiness for anabolic signals.

Furthermore, exercise directly influences the body’s endocrine milieu. Acute bouts of intense exercise can transiently elevate endogenous growth hormone levels, which, when combined with growth hormone-releasing peptides (GHRPs) or growth hormone-releasing hormones (GHRHs), can lead to a more sustained and pulsatile release of GH.

This sustained elevation provides a more consistent anabolic stimulus, supporting both muscle protein synthesis and fat metabolism. The type and intensity of exercise also dictate the specific cellular adaptations, with resistance training being paramount for muscle hypertrophy and strength development.

- Resistance Training ∞ Creates mechanical tension and metabolic stress, upregulating growth factor receptors and enhancing nutrient delivery to muscle cells.

- Cardiovascular Exercise ∞ Improves vascularity and mitochondrial density, enhancing nutrient and oxygen delivery, which supports overall cellular health and recovery.

- Progressive Overload ∞ Continuously challenges muscle fibers, signaling the need for adaptation and growth, thereby maintaining a responsive cellular state.

Dietary Strategies for Cellular Synergy

Nutrition provides the raw materials and crucial signaling molecules that interact with peptide action at a fundamental level. Adequate protein intake, particularly rich in essential amino acids, is indispensable for muscle protein synthesis. When peptides like Ipamorelin or CJC-1295 stimulate GH release, the body requires a readily available supply of amino acids to construct new muscle tissue.

The timing of protein intake around exercise can also influence the magnitude of the anabolic response, though total daily protein remains the dominant factor.

Beyond protein, carbohydrate management plays a significant role in metabolic function and insulin sensitivity. Insulin, a potent anabolic hormone, facilitates the uptake of glucose and amino acids into muscle cells. Maintaining healthy insulin sensitivity through balanced carbohydrate intake and regular physical activity ensures that muscle cells efficiently utilize nutrients, thereby optimizing the environment for peptide-induced growth.

Micronutrients, often overlooked, function as cofactors in countless biochemical reactions, including those vital for hormone synthesis and cellular repair. A deficiency in key vitamins or minerals can impede the entire anabolic cascade, irrespective of peptide intervention.

| Nutrient Category | Role in Muscle Anabolism | Synergistic Effect with Peptides |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Protein | Provides essential amino acids for muscle protein synthesis. | Supplies building blocks for new muscle tissue when peptides stimulate growth pathways. |

| Complex Carbohydrates | Replenishes glycogen stores, supports energy demands, influences insulin sensitivity. | Maintains optimal insulin levels, facilitating amino acid and glucose uptake into peptide-responsive cells. |

| Healthy Fats | Supports hormone production, reduces inflammation, provides sustained energy. | Contributes to cellular membrane integrity and a favorable inflammatory profile, enhancing receptor function. |

| Micronutrients | Cofactors for enzymatic reactions, antioxidant defense, cellular signaling. | Ensures efficient operation of all biochemical pathways influenced by peptides. |

Molecular Mechanisms of Lifestyle-Peptide Synergy

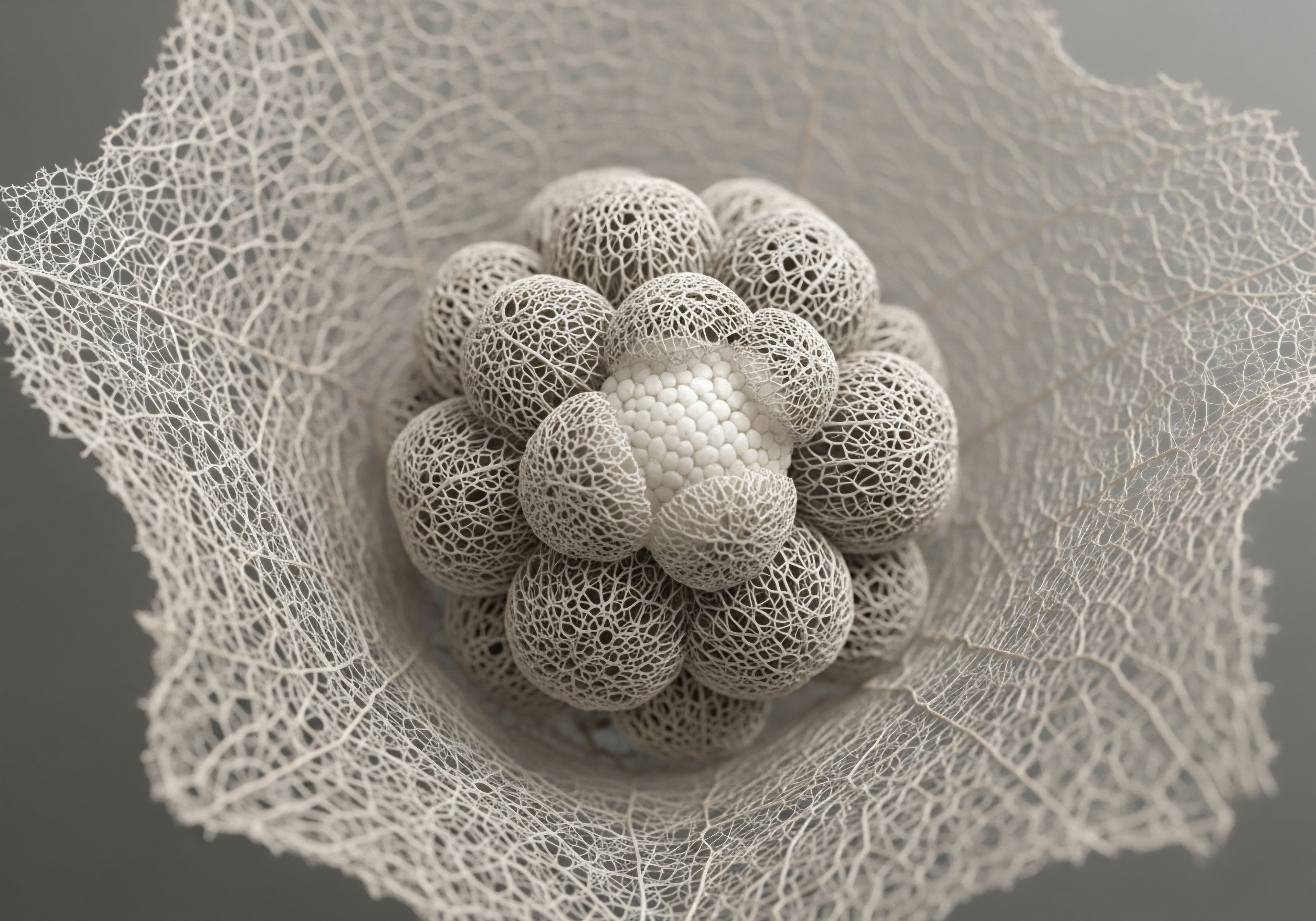

For those seeking a deeper intellectual engagement with the topic, the intricate molecular cross-talk between lifestyle factors and peptide signaling offers a compelling area of study. The amplification of peptide effects by diet and exercise is not a mere additive process; it represents a profound synergistic integration at the cellular and genetic levels.

This complex interplay involves the modulation of receptor expression, activation of intracellular signaling cascades, and epigenetic modifications that collectively prime the muscle cell for an enhanced anabolic response. Our exploration here centers on the sophisticated mechanisms by which these extrinsic stimuli fundamentally alter the intrinsic responsiveness of muscle tissue.

Consider the muscle cell as a highly sophisticated computational unit, constantly processing inputs from its environment. Peptides deliver specific data packets, yet the processing power and efficiency of this unit are dictated by the underlying health and metabolic state of the cell.

When lifestyle factors are optimally aligned, they enhance the cell’s processing capabilities, leading to a more robust and precise execution of the peptide’s directives. This enhanced responsiveness can be traced through several key molecular pathways that converge to regulate muscle protein turnover and cellular adaptation.

Lifestyle factors synergistically integrate with peptide signaling at molecular and genetic levels, enhancing muscle cell responsiveness.

Receptor Dynamics and Signaling Pathway Potentiation

The initial point of interaction for many peptides involves binding to specific cell surface receptors. The number and sensitivity of these receptors are not static; they are dynamically regulated by environmental cues. Resistance exercise, for instance, can lead to the upregulation of growth hormone and IGF-1 receptors on muscle cells, rendering them more receptive to circulating peptides and endogenously released growth factors.

This increased receptor density translates into a more pronounced downstream signaling response, even with the same concentration of peptide. The heightened expression of these receptors ensures that the muscle cell is poised to interpret and act upon anabolic signals with greater fidelity.

Following receptor binding, peptides initiate complex intracellular signaling cascades. A primary pathway involved in muscle anabolism is the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. Exercise, particularly resistance training, directly activates mTOR through mechanical and metabolic sensors. Concurrently, peptides that stimulate GH/IGF-1 release also converge on the mTOR pathway, leading to a dual activation that profoundly amplifies muscle protein synthesis.

Dietary protein, especially leucine, further augments mTOR activation, providing the necessary amino acid substrates and signaling molecules for this pathway to operate optimally. This multi-point activation creates a powerful anabolic stimulus that is far greater than any single intervention could achieve alone.

- Mechanotransduction ∞ Resistance exercise triggers cellular mechanosensors, initiating signaling pathways that contribute to mTOR activation and gene expression related to muscle growth.

- Growth Factor Upregulation ∞ Exercise and specific peptides induce the release of local and systemic growth factors, which further potentiate anabolic signaling within muscle cells.

- Nutrient Sensing ∞ Dietary components, particularly amino acids and glucose, are sensed by intracellular pathways that directly influence mTOR activity and insulin signaling, creating a receptive environment for peptide action.

Metabolic Flexibility and Epigenetic Modulation

Metabolic flexibility, the capacity of muscle cells to readily switch between fuel sources (glucose and fatty acids), represents another critical aspect of lifestyle-peptide synergy. Regular exercise and a well-structured diet enhance metabolic flexibility, improving insulin sensitivity and mitochondrial function.

This allows muscle cells to efficiently manage energy demands during and after exercise, optimizing recovery and creating an energetically favorable environment for anabolic processes. Peptides like Tesamorelin, which influence fat metabolism, can further support this metabolic adaptability, contributing to a leaner and more responsive cellular phenotype.

Furthermore, lifestyle factors exert influence at the epigenetic level, modulating gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Exercise and nutrition can induce specific epigenetic changes, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, that can alter the accessibility of genes involved in muscle growth and repair.

These epigenetic marks can persist, creating a long-term “memory” within muscle cells that enhances their responsiveness to future anabolic stimuli, including those delivered by peptides. This profound level of regulation underscores how deeply integrated lifestyle is with the fundamental biological machinery governing muscle adaptation.

| Molecular Pathway | Lifestyle Influence | Peptide Interaction | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| mTOR Pathway | Activated by resistance exercise and dietary amino acids. | Augmented by GH/IGF-1 signaling from GHS peptides. | Increased muscle protein synthesis and hypertrophy. |

| Insulin Signaling | Improved by exercise and balanced carbohydrate intake. | Enhances glucose and amino acid uptake, synergistic with anabolic peptides. | Optimized nutrient partitioning and cellular energy. |

| Satellite Cell Activation | Stimulated by muscle damage from resistance exercise. | Promoted by GH/IGF-1, facilitating muscle repair and growth. | Enhanced regenerative capacity and myonuclear accretion. |

| Gene Expression | Modulated by exercise-induced epigenetic changes. | Directs synthesis of structural proteins and growth factors. | Long-term adaptation and enhanced anabolic potential. |

References

- Crist, David M. et al. “Effect of growth hormone and resistance exercise on muscle growth in young men.” American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 262, no. 5, 1991, pp. E637-E640.

- Păduraru, Liviu, et al. “Emerging Therapeutic Strategies in Sarcopenia ∞ An Updated Review on Pathogenesis and Treatment Advances.” Pharmaceuticals, vol. 15, no. 10, 2022, p. 1294.

- Morton, Robert W. et al. “Recent Perspectives Regarding the Role of Dietary Protein for the Promotion of Muscle Hypertrophy with Resistance Exercise Training.” Nutrients, vol. 10, no. 2, 2018, p. 198.

- Cocks, Michelle, et al. “Exercising for Insulin Sensitivity ∞ Is There a Mechanistic Relationship With Quantitative Changes in Skeletal Muscle Mass?” Frontiers in Physiology, vol. 12, 2021, p. 656909.

- Schoenfeld, Brad J. Alan Aragon, and James W. Krieger. “The effect of protein timing on muscle strength and hypertrophy ∞ a meta-analysis.” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, vol. 10, no. 1, 2013, p. 53.

- Figueiredo, Vanessa C. et al. “Molecular Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Growth and Organelle Biosynthesis ∞ Practical Recommendations for Exercise Training.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 18, no. 22, 2021, p. 11986.

- Liu, Fan, et al. “Protein, amino acid, and peptide supplementation for the treatment of sarcopaenia.” Endokrynologia Polska, vol. 74, no. 2, 2023, pp. 140-143.

- Sigal, Ronald J. et al. “Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes ∞ a randomized trial.” Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 147, no. 6, 2007, pp. 357-369.

Reflection on Your Personal Health Journey

As we conclude this exploration of peptide action and its amplification through lifestyle, consider the profound implications for your own health trajectory. The knowledge acquired here represents a powerful lens through which to view your biological systems, not as a collection of isolated parts, but as an exquisitely interconnected whole.

This understanding is the initial step in a personal journey, inviting you to engage proactively with your body’s inherent capacity for adaptation and repair. Your unique physiology holds the blueprint for reclaiming robust function and sustained vitality.

The path toward optimal well-being is deeply personal, requiring an ongoing dialogue between objective scientific principles and your subjective lived experience. Recognize that true wellness protocols are never one-size-fits-all; they are instead meticulously tailored to the individual’s specific needs, responses, and aspirations. This commitment to personalized guidance ensures that every intervention, every dietary adjustment, and every exercise choice serves to enhance your intrinsic biological intelligence, moving you closer to a state of uncompromised health.