Fundamentals

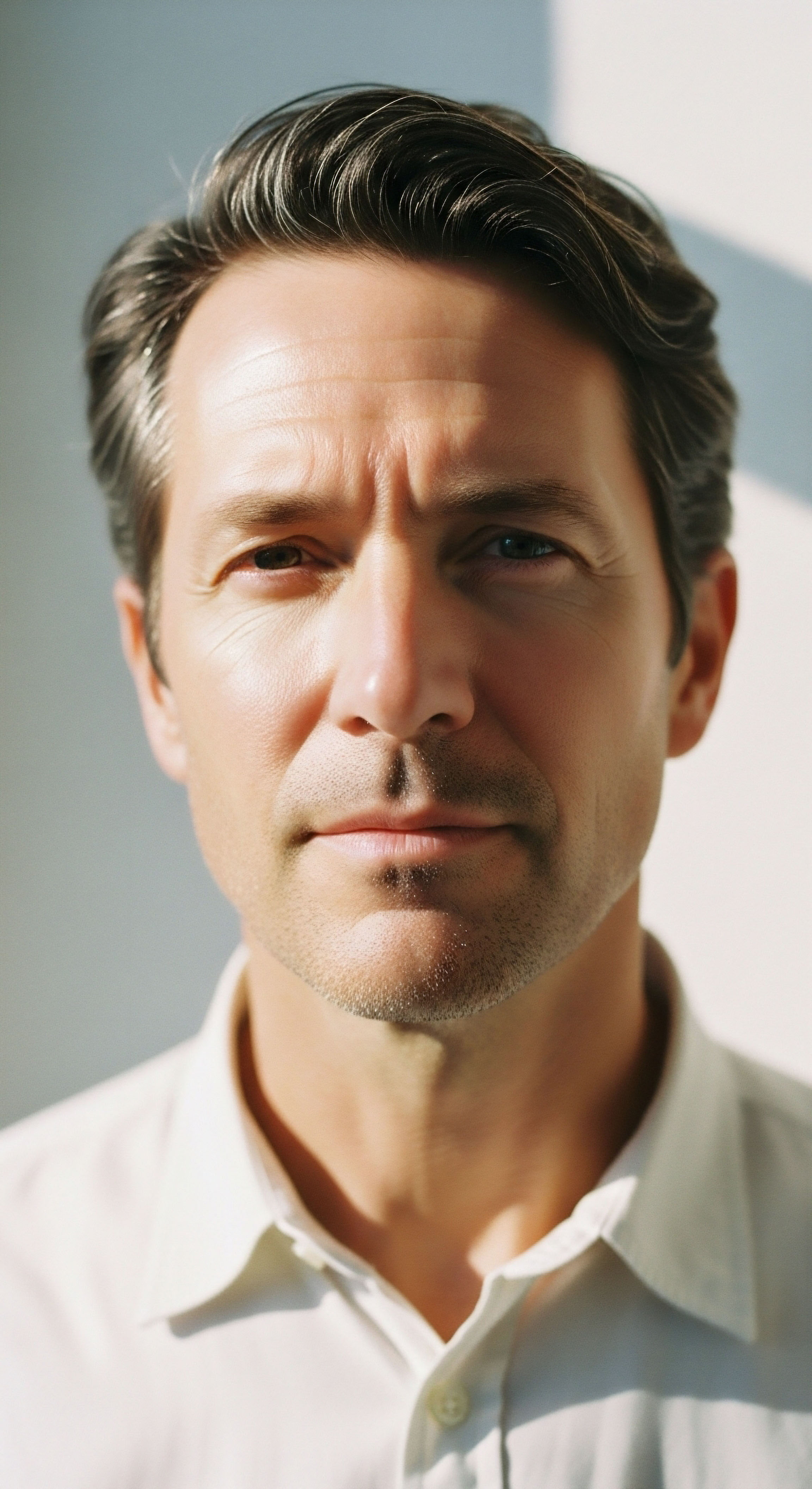

You may have noticed it yourself ∞ a change in the reflection looking back at you that seems to tell a story of your recent life. After a period of intense stress or poor sleep, your face might appear fuller, less defined.

Conversely, a week of restorative rest and nourishing meals can bring back a sense of vitality to your features. This lived experience is a powerful observation. It points to a profound biological truth ∞ the appearance of our face, particularly the soft contours shaped by fatty tissue and fluid, is a sensitive barometer of our internal metabolic environment. Your lifestyle choices are the primary architects of this environment.

The conversation about facial composition often begins and ends with genetics and hormones. While your underlying bone structure is genetically determined and sex hormones like estrogen and testosterone set a baseline for fat distribution, the day-to-day, year-to-year appearance of your face is dynamically sculpted by your actions.

The choices you make regarding nutrition, physical activity, stress modulation, and sleep quality exert a significant influence on your facial aesthetics. These choices operate through precise physiological channels, speaking directly to the systems that regulate where and how your body stores energy and fluid.

Your daily habits directly instruct the key metabolic hormones that regulate how your body stores fat and fluid, which is often visibly reflected in your face.

The Primary Lifestyle Inputs

Understanding how to influence facial fat distribution begins with appreciating the four pillars of metabolic wellness. Each one sends powerful signals throughout your body, creating a cascade of effects that can alter your facial contours.

Nourishment and Hydration

The food you consume provides the building blocks and energy for every cell in your body. A diet rich in processed foods and refined carbohydrates can create a state of low-grade inflammation and disrupt key metabolic hormones. Sodium intake has a direct relationship with how much water your body retains. Proper hydration, conversely, is essential for cellular function and helps regulate fluid balance, preventing the puffiness that can obscure facial definition.

Movement and Physical Activity

Regular exercise is a potent tool for influencing body composition. Cardiovascular activities help create the necessary energy deficit for overall fat loss, which naturally includes fat stored in facial tissues. Strength training builds metabolically active muscle, which improves your body’s ability to manage blood sugar and insulin. This systemic improvement has consequences for fat storage everywhere, including the face.

Stress and Recovery

Your body’s response to stress is a primitive survival mechanism. In the modern world, chronic psychological stress can lead to the sustained release of the hormone cortisol. This powerful chemical messenger can alter metabolism, encourage fat storage in specific areas like the abdomen and face, and promote fluid retention. Effectively managing stress and prioritizing recovery are essential for normalizing this system.

Sleep Quality

Sleep is a critical period for hormonal regulation and cellular repair. Insufficient or poor-quality sleep disrupts the delicate balance of numerous hormones, including cortisol and those that regulate appetite. Over time, this disruption can contribute to weight gain and the associated changes in facial fat distribution.

Intermediate

To appreciate how lifestyle choices sculpt facial contours, we must look at the specific biological mechanisms they trigger. The connection is made through the body’s intricate endocrine system, a network of glands that produce hormones. These chemical messengers travel through the bloodstream, delivering instructions to various tissues. Two of the most influential hormones in this context are cortisol and insulin, both of which are exquisitely sensitive to your daily habits.

The Cortisol Connection and Facial Puffiness

Cortisol is your primary stress hormone, produced by the adrenal glands in response to signals from the brain via the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. This system is designed for acute, short-term stressors. When stress becomes chronic ∞ due to work pressure, lack of sleep, or emotional strain ∞ the HPA axis can become persistently activated, leading to chronically elevated cortisol levels.

Elevated cortisol has two distinct effects on facial appearance:

- Fluid Retention ∞ High cortisol levels can influence the hormone aldosterone, which instructs the kidneys to retain sodium and excrete potassium. This sodium retention causes your body to hold onto more water, leading to a generalized puffiness or edema. The soft tissues of the face are particularly susceptible to this effect, which can create a swollen or bloated appearance.

- Fat Redistribution ∞ Chronically high cortisol promotes a process called lipogenesis, or the creation of fat. It specifically encourages the deposition of visceral fat around the organs and, notably, in the face and neck. This can result in a rounder facial shape, often referred to in clinical settings as “moon facies,” a hallmark of conditions involving excess cortisol.

Chronic stress elevates the hormone cortisol, which can lead to both fluid retention and the strategic deposition of fat in facial tissues.

Insulin Resistance and Facial Adiposity

Insulin is a hormone produced by the pancreas. Its primary job is to help your cells take up glucose from the bloodstream for energy. When you consume a diet high in refined carbohydrates and sugars, your pancreas must release large amounts of insulin to manage the resulting surge in blood glucose.

Over time, your cells can become less responsive to insulin’s signal, a condition known as insulin resistance. This forces the pancreas to produce even more insulin to get the job done, leading to a state of hyperinsulinemia (chronically high insulin levels).

High insulin levels are a powerful signal for your body to store fat. Research suggests a correlation between facial fat and visceral abdominal fat, both of which are linked to insulin resistance. While overall weight gain from any cause will increase facial fat, the metabolic state of insulin resistance creates a particularly strong drive for fat accumulation. Some research even posits that facial fat could serve as a visible marker for underlying insulin resistance.

How Do Lifestyle Protocols Target These Pathways?

Lifestyle interventions are effective because they directly address the root causes of cortisol and insulin dysregulation.

| Lifestyle Factor | Mechanism of Action | Effect on Facial Appearance |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Modification | Reducing refined carbohydrates and sugars lowers the demand for insulin, improving insulin sensitivity over time. Limiting sodium intake reduces water retention. | Decreases the hormonal drive for fat storage and reduces puffiness and bloating. |

| Consistent Exercise | Cardio exercise promotes overall fat loss. Strength training builds muscle, which acts as a glucose sink, improving insulin sensitivity. Exercise can also help regulate cortisol. | Reduces overall body fat, leading to a leaner facial appearance. Improves metabolic health. |

| Stress Management | Practices like meditation, deep breathing, and adequate leisure time down-regulate the HPA axis, lowering chronic cortisol production. | Reduces cortisol-driven fluid retention and fat redistribution in the face. |

| Prioritizing Sleep | Adequate sleep (7-9 hours) is essential for resetting the HPA axis and maintaining insulin sensitivity. Poor sleep is a direct stressor that elevates cortisol. | Supports hormonal balance, preventing the facial puffiness and metabolic disruption associated with sleep deprivation. |

Academic

A sophisticated understanding of facial fat distribution requires a systems-biology perspective, viewing the face as a reflection of complex, interconnected physiological networks. Lifestyle choices do not simply add or subtract calories; they modulate the very signaling environment in which our cells operate. The conversation moves from simple cause-and-effect to the interplay between the HPA axis, insulin signaling pathways, and the biology of adipose tissue itself.

Adipose Tissue as a Dynamic Endocrine Organ

Adipose tissue is now understood to be a highly active endocrine organ, not merely a passive reservoir for lipid storage. It synthesizes and secretes a wide range of signaling molecules known as adipokines, which have profound effects on appetite, inflammation, and insulin sensitivity. Importantly, different fat depots have distinct metabolic characteristics. Visceral adipose tissue (VAT), located deep within the abdominal cavity, is known to be more metabolically active and pro-inflammatory than subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT).

Emerging research has drawn parallels between the metabolic properties of VAT and certain facial fat pads, such as buccal fat. This suggests that an accumulation of facial fat may be more than a cosmetic issue; it could be a physical manifestation of the same metabolic dysregulation ∞ specifically insulin resistance and chronic inflammation ∞ that characterizes visceral obesity.

Lifestyle factors that promote visceral fat accumulation, such as diets high in fructose and a sedentary lifestyle, would therefore be expected to have a corresponding impact on facial adiposity.

The fat on your face can share metabolic characteristics with deep abdominal fat, making it a potential visual indicator of systemic insulin resistance and inflammation.

What Is the Cellular Basis for Facial Fat Changes?

At the cellular level, hormones like cortisol and insulin exert their effects by binding to specific receptors on fat cells (adipocytes). The density and sensitivity of these receptors can vary between different fat depots. For example, adipocytes in visceral and certain facial regions may have a higher concentration of glucocorticoid receptors, making them more responsive to cortisol’s signal to store fat. Chronic stress, through sustained cortisol elevation, can selectively promote lipid accumulation in these specific areas.

Insulin resistance adds another layer of complexity. In a state of hyperinsulinemia, the powerful anabolic signal of insulin promotes lipogenesis. While muscle and liver cells may be resistant to insulin’s glucose-uptake signal, fat cells often remain sensitive to its fat-storage signal, creating a powerful drive for weight gain. This process is exacerbated by the inflammatory environment created by metabolically unhealthy adipose tissue, establishing a self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation, insulin resistance, and fat accumulation.

Can Lifestyle Choices Mediate Facial Attractiveness through Health?

Recent research has begun to formally investigate the links between lifestyle, health markers, and perceived facial attractiveness. One study found that while factors like exercise and life stress did not directly predict facial attractiveness, they had a significant indirect effect. The pathway was mediated through changes in body fat (measured by skinfold thickness) and subsequent poor health symptoms.

This provides evidence for a clear, measurable pathway ∞ lifestyle choices (stress, exercise) influence body composition, which in turn impacts health status, and this entire complex is ultimately reflected in facial appearance.

| Factor | Primary Hormone(s) Affected | Cellular/Systemic Mechanism | Observable Facial Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Stress | Cortisol | Activation of HPA axis; increased glucocorticoid receptor binding in susceptible fat depots; aldosterone-mediated fluid retention. | Increased facial and neck fat deposition (moon facies); facial puffiness. |

| High Glycemic Diet | Insulin | Hyperinsulinemia promotes lipogenesis; potential for increased androgen activity; promotes inflammation. | Increased overall facial adiposity; potential for hormonal acne. |

| Sleep Deprivation | Cortisol, Ghrelin, Leptin | Acts as a physiological stressor, increasing cortisol; disrupts appetite-regulating hormones, promoting caloric surplus. | Facial puffiness; contributes to weight gain and increased facial fat. |

| Regular Exercise | Insulin, Cortisol | Improves insulin sensitivity in muscle tissue; helps regulate cortisol levels; promotes overall energy deficit. | Reduction in overall body fat, leading to leaner facial features. |

This academic viewpoint reframes the question. Lifestyle choices significantly influence facial fat distribution because they are the most powerful tools we have to control the hormonal and inflammatory signaling that dictates adipose tissue behavior throughout the body.

References

- Sierra-Johnson, J. & Johnson, B. D. (2004). Facial fat and its relationship to abdominal fat ∞ a marker for insulin resistance?. Medical hypotheses, 63(5), 783 ∞ 786.

- Kahn, S. E. Hull, R. L. & Utzschneider, K. M. (2006). Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature, 444(7121), 840 ∞ 846.

- White, D. & Reeve, K. (2024). Do lifestyle and hormonal variables explain links between health and facial attractiveness?. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1404387.

- Epel, E. S. McEwen, B. Seeman, T. Matthews, K. Castellazzo, G. Brownell, K. D. Bell, J. & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Stress and body shape ∞ stress-induced cortisol secretion is consistently greater among women with central fat. Psychosomatic medicine, 62(5), 623 ∞ 632.

- Newell-Price, J. Bertagna, X. Grossman, A. B. & Nieman, L. K. (2006). Cushing’s syndrome. The Lancet, 367(9522), 1605 ∞ 1617.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a biological framework for understanding the changes you observe in your own body. It connects your daily actions to the intricate hormonal symphony playing out within you. This knowledge is a starting point. It equips you with the understanding that your body is constantly listening and responding to the signals you provide through your lifestyle.

Your personal health journey is unique, and recognizing the power you hold to influence your own physiology is the first, most definitive step toward reclaiming a state of vitality that is reflected from the inside out.