Fundamentals

The feeling is unmistakable. It is a subtle, persistent sense that your internal landscape has shifted. Perhaps it manifests as a pervasive fatigue that sleep does not resolve, a mental fog that clouds focus, or a frustrating change in your body’s composition despite your best efforts with diet and exercise.

You may notice a decline in your drive, your mood, or your overall sense of vitality. This experience, this felt sense of being out of sync with your own biology, is a valid and powerful signal. It is your body communicating a change in its intricate internal operating system. The question of whether lifestyle adjustments can fundamentally alter this state before considering clinical interventions is a profound one. The answer lies in understanding the architecture of your own physiology.

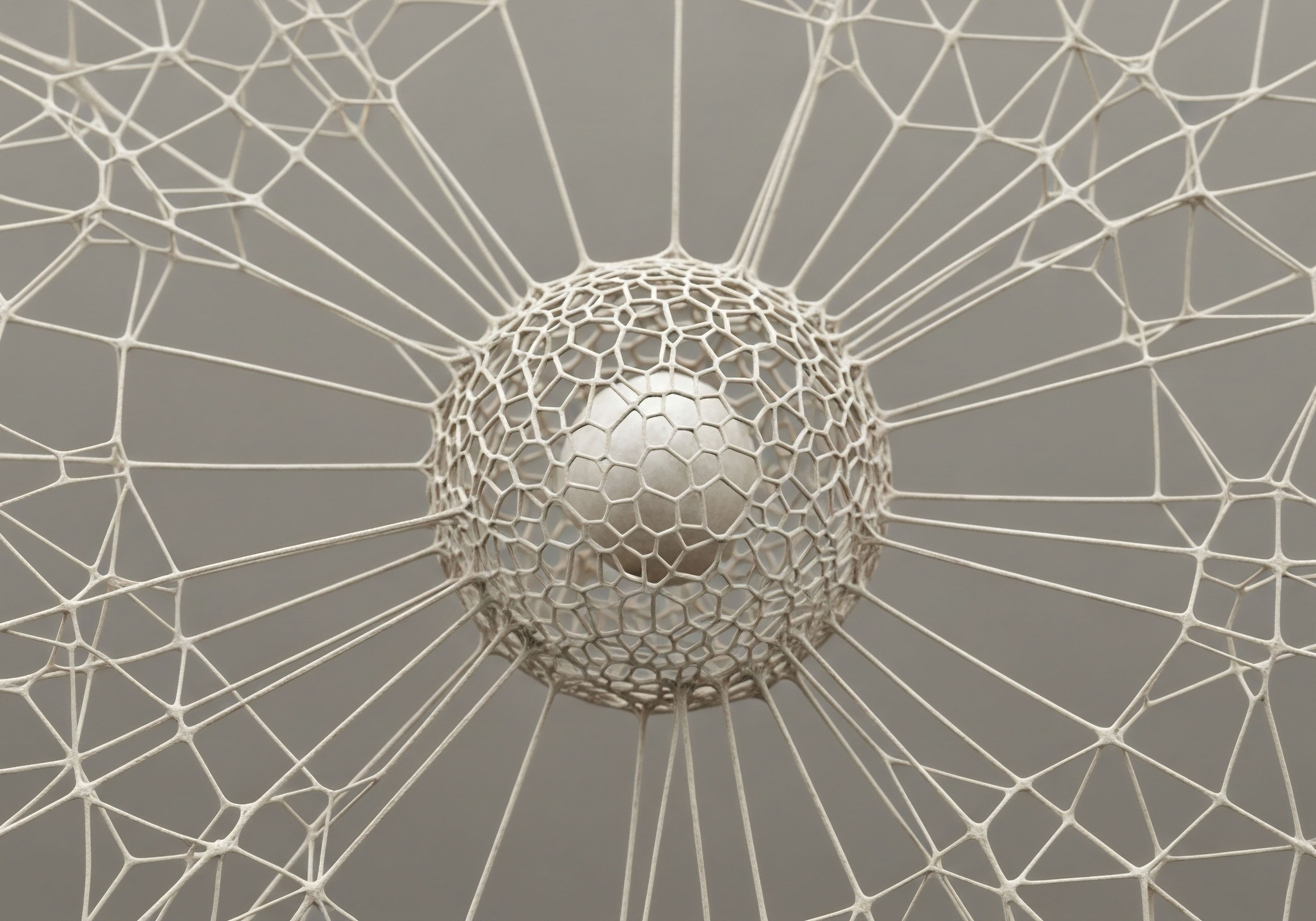

Your body functions as a cohesive whole, governed by a sophisticated communication network known as the endocrine system. This system uses chemical messengers, hormones, to transmit information between cells and organs, coordinating everything from your metabolism and energy levels to your mood and reproductive capacity.

At the heart of this network, particularly concerning vitality and reproductive health, lies the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Think of this as the central command and control for your body’s most powerful hormones. The hypothalamus, a small region in your brain, acts as the system’s director.

It continuously monitors your internal and external environment, gathering data on your stress levels, nutritional status, and sleep patterns. Based on this data, it sends a precise signal, Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), to the pituitary gland.

The pituitary, receiving its instructions, then releases two other messengers into the bloodstream ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These hormones travel to the gonads ∞ the testes in men and the ovaries in women. In response, the gonads produce the primary sex hormones ∞ testosterone in men, and estrogen and progesterone in women.

These powerful molecules are responsible for a vast array of functions that define your sense of well-being. They build muscle, maintain bone density, regulate libido, support cognitive function, and contribute to a stable mood.

The system completes its circuit through a process of feedback, where the levels of these end-point hormones signal back to the hypothalamus and pituitary, instructing them to either increase or decrease their signaling. This elegant feedback loop is designed to maintain a state of dynamic equilibrium, a biological harmony known as homeostasis.

Your daily choices directly inform the signaling cascade that governs your body’s hormonal equilibrium.

The System Is Responsive

The critical insight here is that the HPG axis is a dynamic and responsive system. It is designed to adapt. The signals it sends are directly influenced by the information it receives from your daily life. Your nutrition provides the raw materials for hormone production.

Your sleep quality dictates the timing and volume of hormonal release. Your management of stress determines whether the system operates in a state of calm efficiency or high alert. When you feel that persistent sense of being “off,” it is often because this finely calibrated system has been pushed out of its optimal range by consistent, cumulative lifestyle inputs.

The fatigue, the mental fog, the changes in body composition ∞ these are the downstream consequences of a communication breakdown in your internal network.

Therefore, the capacity for lifestyle changes to improve hormone levels is rooted in this biological reality. By systematically addressing the foundational pillars of your health, you are providing the HPG axis with the precise inputs it needs to recalibrate itself. You are speaking to your own biology in its native language.

This process involves supplying the correct molecular building blocks through targeted nutrition, creating the necessary restorative conditions through optimized sleep, and mitigating the disruptive signals that come from unmanaged stress. Each of these pillars represents a powerful lever you can pull to influence your hormonal state. The journey begins with recognizing that your symptoms are real, they have a biological basis, and you possess a significant degree of agency in addressing them at their source.

What Are the Primary Inputs to Your Hormonal System?

The regulation of your endocrine system is a reflection of how your body interprets the world. The primary inputs it assesses are nourishment, restoration, and threat. These translate directly to the pillars of diet, sleep, and stress. A diet lacking in specific micronutrients or healthy fats deprives the body of the essential components needed to synthesize testosterone or estrogen.

Inadequate sleep, particularly the deep stages, directly blunts the nocturnal surge of growth hormone and testosterone that is critical for repair and vitality. Chronic stress elevates cortisol, a hormone that, in a state of persistent activation, actively suppresses the HPG axis, effectively telling your body that it is not a safe time for procreation or rebuilding. Understanding these inputs allows you to move from a passive experience of symptoms to an active role in managing your own physiological environment.

This perspective shifts the conversation from one of disease to one of function. The goal becomes restoring the body’s innate capacity for self-regulation. It is a process of removing the obstacles that are disrupting the system and providing the resources it needs to find its equilibrium. This is the foundational principle upon which any effective wellness protocol is built, and it is the essential first step in any journey toward reclaiming your vitality.

Intermediate

Understanding that your daily habits are direct inputs into your hormonal command center, the HPG axis, is the first step. The next is to learn how to manipulate these inputs with clinical precision. This involves moving beyond general advice and adopting specific, evidence-based strategies for nutrition, sleep, and stress modulation.

Each of these pillars functions as a powerful tool for biochemical recalibration. By systematically optimizing them, you provide your endocrine system with the unambiguous signals required to restore its intended function. This is the practical application of personalized wellness, where you actively participate in the orchestration of your own physiology.

Nutritional Protocols for Hormonal Optimization

The food you consume provides the literal building blocks for your hormones. Steroid hormones, including testosterone and estrogen, are synthesized from cholesterol. The quality of fats in your diet, therefore, has a direct impact on the availability of this essential precursor.

Furthermore, the balance of macronutrients ∞ protein, fats, and carbohydrates ∞ influences the intricate dance of hormones like insulin and cortisol, which in turn affect the HPG axis. A diet designed for hormonal health is one that provides all necessary cofactors and maintains metabolic stability.

Macronutrient Architecture and Hormonal Response

Your dietary composition sends powerful signals to your endocrine system. Each macronutrient plays a distinct role in this communication.

- Fats They are the direct precursors to steroid hormones. Research indicates that diets with adequate healthy fats are associated with higher testosterone levels. Monounsaturated fats (found in avocados, olive oil, and almonds) and certain saturated fats (from sources like coconut oil and grass-fed butter) are particularly important for providing the cholesterol backbone for hormone synthesis. Conversely, diets that are excessively low in fat can lead to a measurable decrease in testosterone production. Polyunsaturated fats, while essential, require balance, as some studies suggest very high intakes might suppress testosterone levels.

- Proteins Adequate protein intake is necessary for maintaining muscle mass, which is metabolically active tissue that supports healthy insulin sensitivity and overall hormonal balance. It also provides the amino acids required for the production of peptide hormones and neurotransmitters. However, an excessively high protein intake at the expense of fats and carbohydrates may lead to a reduction in testosterone. The key is a balanced approach, sourcing protein from lean meats, fish, eggs, and well-prepared legumes.

- Carbohydrates Carbohydrates play a crucial role in supporting testosterone levels, primarily by managing cortisol. Intense exercise and restrictive low-carbohydrate diets can elevate cortisol, which has an antagonistic relationship with testosterone. Consuming complex carbohydrates from sources like root vegetables, whole fruits, and whole grains helps replenish glycogen stores and keeps cortisol in check, creating a more favorable anabolic environment. Refined sugars and processed carbohydrates, on the other hand, can lead to insulin resistance, a condition strongly linked to hormonal dysregulation in both men and women.

Micronutrient Cofactors for Endocrine Function

Beyond macronutrients, specific vitamins and minerals act as essential cofactors in the enzymatic pathways of hormone production. Deficiencies in these key micronutrients can create significant bottlenecks in the system.

Key micronutrients include:

- Zinc This mineral is critical for the production of testosterone. It acts as a modulator within the hypothalamus, helping to regulate the release of GnRH. A deficiency in zinc is directly correlated with lower testosterone levels.

- Vitamin D Often called the “sunshine vitamin,” Vitamin D functions as a steroid hormone in the body. Its receptors are found on cells in the hypothalamus, pituitary, and gonads. Studies have shown a strong correlation between sufficient Vitamin D levels and healthy testosterone concentrations.

- Magnesium This mineral is involved in over 300 enzymatic reactions in the body, including those related to sleep, stress management, and hormone production. It can help improve sleep quality and may reduce the binding of testosterone to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), thereby increasing the amount of free, bioavailable testosterone.

| Nutrient | Function | Primary Food Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy Fats | Precursor for steroid hormone production (testosterone, estrogen). | Avocado, olive oil, coconut oil, nuts, seeds, fatty fish (salmon). |

| Quality Protein | Supports muscle mass, provides amino acids for peptide hormones. | Grass-fed beef, wild-caught fish, pasture-raised eggs, lentils. |

| Complex Carbs | Manages cortisol levels, provides energy for metabolic processes. | Sweet potatoes, quinoa, berries, leafy green vegetables. |

| Zinc | Essential for testosterone synthesis and GnRH regulation. | Oysters, beef, pumpkin seeds, lentils. |

| Vitamin D | Functions as a hormone, supports testicular and ovarian function. | Sunlight exposure, fatty fish, fortified milk, egg yolks. |

Sleep Architecture as a Hormone Regulator

Sleep is a fundamental pillar of endocrine health. During sleep, the body undergoes critical processes of repair, consolidation, and hormonal secretion. The architecture of your sleep ∞ the cyclical progression through different stages ∞ is directly linked to the release of key anabolic hormones, including Growth Hormone (GH) and testosterone. Chronic sleep disruption is one of the most direct ways to suppress your hormonal output.

The majority of your daily testosterone and growth hormone is secreted during the deep stages of sleep.

How Does Sleep Deprivation Impact Hormones?

The impact of poor sleep on your hormonal system is both immediate and cumulative. The most significant release of GH occurs during the first few hours of sleep, in conjunction with slow-wave sleep (SWS), also known as deep sleep. This GH pulse is vital for tissue repair, muscle growth, and overall cellular rejuvenation.

Similarly, testosterone levels begin to rise upon falling asleep, peaking during the first REM cycle and remaining elevated until awakening. When sleep is shortened or fragmented, you are directly truncating these critical secretory periods. One study demonstrated that just one week of sleeping five hours per night reduced testosterone levels in healthy young men by 10-15%, an effect equivalent to aging 10 to 15 years. This illustrates the profound and rapid impact of sleep deprivation on the HPG axis.

Stress, Cortisol, and the HPG Axis Suppression

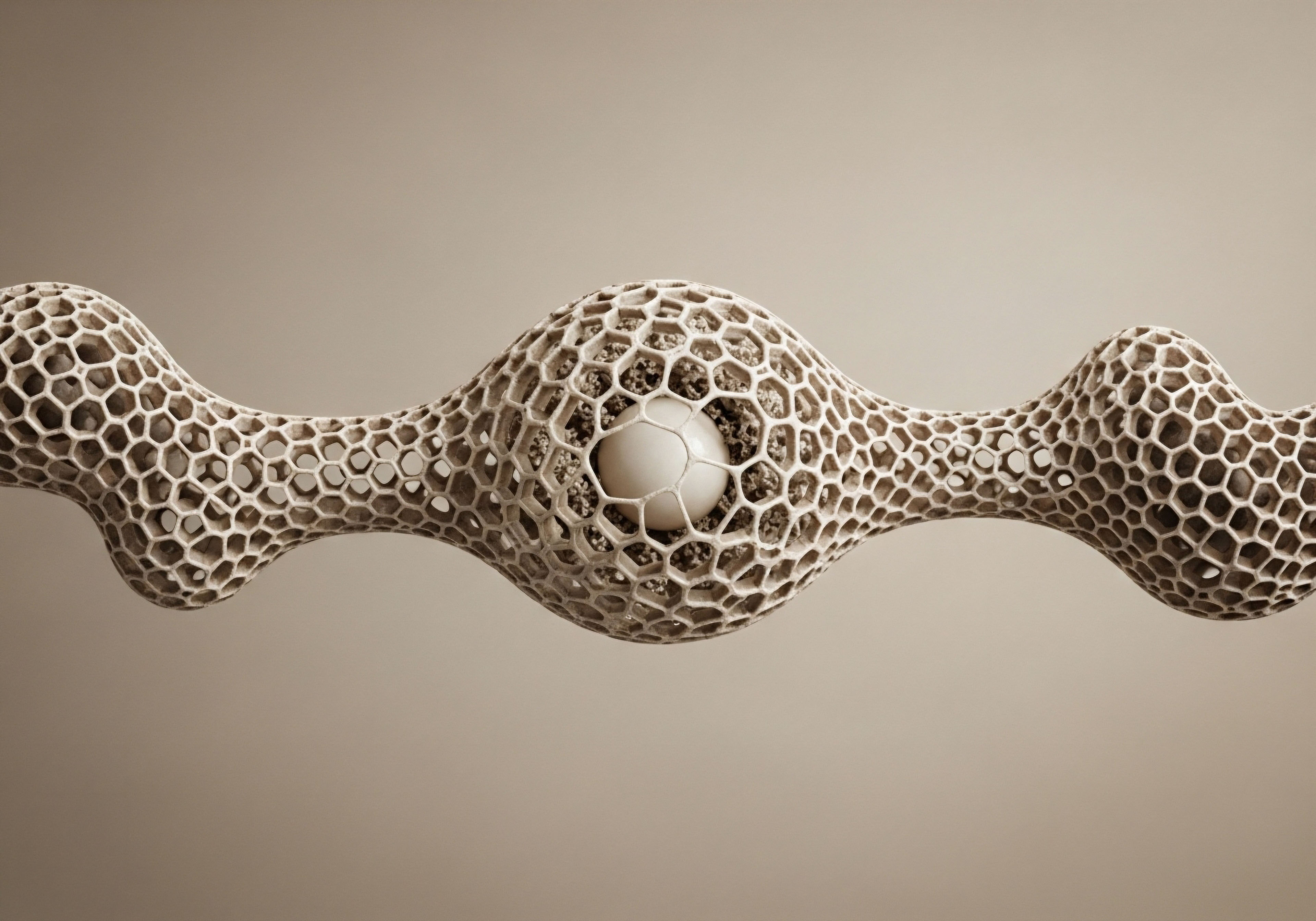

The body’s stress response system, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, has a powerful and often dominant relationship with the HPG axis. When you perceive a threat ∞ whether it is a physical danger or a psychological stressor like a work deadline ∞ the HPA axis is activated, culminating in the release of cortisol from the adrenal glands.

In the short term, this is a vital survival mechanism. However, in the context of modern life, this system is often chronically activated, leading to persistently elevated cortisol levels.

Chronic cortisol elevation sends a powerful signal to the body that it is in a state of emergency. From a biological perspective, long-term survival takes precedence over functions like reproduction and rebuilding. As a result, elevated cortisol actively suppresses the HPG axis at multiple levels.

It can reduce the brain’s production of GnRH, blunt the pituitary’s release of LH, and directly impair the function of the Leydig cells in the testes and theca cells in the ovaries, reducing the production of testosterone and estrogen. Effectively managing stress is therefore a non-negotiable component of any serious attempt to optimize hormone levels naturally.

This involves implementing practices like mindfulness, meditation, breathwork, or spending time in nature to down-regulate the HPA axis and lower circulating cortisol levels, allowing the HPG axis to resume its normal function.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of hormonal regulation requires an appreciation of the intricate molecular dialogues between the body’s major signaling networks. The question of whether lifestyle can modulate hormone levels finds its deepest validation in the biochemical interplay between the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.

Chronic psychological, metabolic, or inflammatory stress creates a state of sustained HPA activation, characterized by elevated levels of glucocorticoids, primarily cortisol. This state of hypercortisolism exerts a profound and direct inhibitory influence on the HPG axis, a mechanism that is conserved across species as a means of prioritizing survival over reproduction during periods of sustained threat. Understanding this interaction at the cellular and molecular level reveals precisely how lifestyle interventions that mitigate stress can restore gonadal function.

Glucocorticoid-Mediated Suppression of the HPG Axis

The inhibitory effects of glucocorticoids on the reproductive axis are multifaceted, occurring at all three levels of the HPG hierarchy ∞ the hypothalamus, the pituitary, and the gonads themselves. This multi-level suppression ensures a robust shutdown of reproductive investment during periods of chronic stress.

Central Inhibition at the Hypothalamus and Pituitary

At the apex of the HPG axis, the hypothalamus, glucocorticoids act to suppress the synthesis and pulsatile release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH). This is achieved through several mechanisms. Glucocorticoids can directly act on GnRH neurons, which express glucocorticoid receptors (GR), to reduce GnRH gene transcription.

Additionally, they stimulate the expression of RFamide-related peptide-3 (RFRP-3), a potent gonadotropin-inhibitory hormone (GnIH), which acts on GnRH neurons to inhibit their activity. This reduction in the primary signaling molecule from the hypothalamus leads to a diminished downstream response.

In the pituitary gland, elevated cortisol levels further dampen the reproductive cascade. Glucocorticoids decrease the sensitivity of pituitary gonadotroph cells to GnRH, meaning that even when GnRH is released, it is less effective at stimulating the secretion of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). This dual-pronged central inhibition ∞ reducing the initial signal and blunting the response to it ∞ effectively throttles the entire hormonal production line from the top down.

Chronic cortisol exposure directly impairs the gonads’ ability to produce testosterone and estrogen at the cellular level.

Direct Peripheral Inhibition at the Gonads

Perhaps the most clinically significant mechanism is the direct action of glucocorticoids on the gonads. Both testicular Leydig cells and ovarian theca and granulosa cells express glucocorticoid receptors, making them direct targets for stress-induced inhibition.

In the testes, cortisol has been shown to suppress testosterone biosynthesis by down-regulating the expression of key steroidogenic enzymes, such as Cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc) and 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase (P450c17). These enzymes are critical for converting cholesterol into androgens. By inhibiting their function, cortisol directly impairs the Leydig cells’ capacity to produce testosterone, irrespective of the level of LH stimulation from the pituitary.

A similar process occurs in the ovaries. High levels of cortisol can disrupt follicular development and inhibit the production of estradiol by granulosa cells. This direct gonadal suppression is a powerful mechanism that explains why individuals under chronic stress can experience symptoms of hypogonadism even with seemingly normal central signaling.

Lifestyle interventions that focus on stress reduction, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) or regular low-intensity exercise, work by lowering circulating glucocorticoid levels, thereby relieving this direct inhibitory pressure on the gonads and allowing steroidogenic pathways to function optimally.

The Role of Sleep Architecture in Anabolic Hormone Pulsatility

The 24-hour patterns of hormone secretion are tightly coupled to the sleep-wake cycle, a phenomenon governed by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus. The pulsatile release of Growth Hormone (GH) and testosterone is not random; it is intricately linked to specific stages of sleep, particularly slow-wave sleep (SWS) and REM sleep. Disruptions to sleep architecture, common in modern society due to factors like light exposure, caffeine use, and alcohol consumption, can profoundly desynchronize these vital hormonal rhythms.

What Is the Mechanism Linking Slow-Wave Sleep to GH Release?

The major pulse of GH secretion in adults occurs shortly after sleep onset, in tight temporal association with the first period of SWS. This process is believed to be driven by a coordinated increase in Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH) and a decrease in somatostatin, the primary inhibitor of GH release, from the hypothalamus.

The neural oscillations that characterize SWS appear to facilitate this hypothalamic signaling environment. Consequently, any factor that reduces the duration or intensity of SWS ∞ such as aging, alcohol consumption, or sleep apnea ∞ will directly reduce the amplitude of this critical GH pulse. This leads to impaired tissue repair, reduced protein synthesis, and a shift toward a more catabolic state, contributing to symptoms of fatigue and poor recovery.

Testosterone secretion follows a similar circadian pattern, with levels rising during sleep to peak in the early morning. This nocturnal rise is dependent on the integrity of sleep cycles. Sleep fragmentation, which prevents the consolidation of deep and REM sleep, has been demonstrated to significantly blunt this nocturnal testosterone surge.

This provides a clear mechanistic link between poor sleep quality and the development of functional hypogonadism. Lifestyle strategies aimed at improving sleep hygiene ∞ such as maintaining a consistent sleep schedule, creating a dark and cool sleep environment, and avoiding stimulants before bed ∞ are direct interventions to protect and optimize this fundamental aspect of endocrine physiology.

| Stressor | Primary Mediator | Molecular Mechanism of Action | Downstream Hormonal Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Psychological Stress | Cortisol (Glucocorticoids) | Binds to GR in hypothalamus, reducing GnRH transcription. Stimulates RFRP-3 (GnIH). Down-regulates steroidogenic enzymes (e.g. P450c17) in gonads. | Decreased LH, FSH, Testosterone, and Estradiol. Suppression of reproductive function. |

| Sleep Deprivation / Fragmentation | Disrupted Circadian Rhythm | Reduces duration and intensity of Slow-Wave Sleep (SWS) and REM sleep. Alters hypothalamic release of GHRH and Somatostatin. | Blunted nocturnal Growth Hormone pulse. Attenuated nocturnal rise in Testosterone. |

| Poor Nutrition (High Refined Carbs) | Insulin Resistance / Inflammation | Chronic hyperinsulinemia increases aromatase activity. Pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. TNF-α, IL-6) suppress Leydig cell function. | Increased conversion of testosterone to estrogen. Reduced testosterone production. |

| Excessive Caloric Restriction | Energy Deficit | Suppression of leptin signaling to the hypothalamus. Activation of HPA axis due to metabolic stress. | Suppression of GnRH pulsatility, leading to functional hypothalamic amenorrhea or hypogonadism. |

References

- Whirledge, S. & Cidlowski, J. A. (2010). Glucocorticoids, stress, and fertility. Minerva endocrinologica, 35(2), 109 ∞ 125.

- Ranabir, S. & Reetu, K. (2011). Stress and hormones. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism, 15(1), 18 ∞ 22.

- Leproult, R. & Van Cauter, E. (2011). Effect of 1 week of sleep restriction on testosterone levels in young healthy men. JAMA, 305(21), 2173 ∞ 2174.

- Muthusami, K. R. & Chinnaswamy, P. (2005). Effect of chronic alcoholism on male fertility hormones and semen quality. Fertility and sterility, 84(4), 919-924.

- Van Cauter, E. L’Hermite-Balériaux, M. Copinschi, G. & Refetoff, S. (1991). The physiology of growth hormone secretion during sleep. The Journal of pediatrics, 119(5), 831-840.

- Joseph, D. N. & Whirledge, S. (2017). Stress and the HPA Axis ∞ Balancing Homeostasis and Fertility. International journal of molecular sciences, 18(10), 2224.

- Mumford, S. L. Chavarro, J. E. Zhang, C. Perkins, N. J. Sjaarda, L. A. Pollack, A. Z. Schliep, K. C. Michels, K. A. Zarek, S. M. Plowden, T. C. Radin, R. G. Messer, L. C. Frankel, R. A. & Wactawski-Wende, J. (2016). Dietary fat intake and reproductive hormone concentrations and ovulation in regularly menstruating women. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 103(3), 868 ∞ 877.

- Pfaus, J. G. (2009). Pathways of sexual desire. The journal of sexual medicine, 6(6), 1506-1533.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here is a map. It details the intricate territories of your internal world, revealing the connections between how you live and how you feel. It illuminates the pathways through which your choices regarding food, sleep, and stress become the chemical messengers that orchestrate your vitality.

This knowledge is designed to be a tool of empowerment, a way to translate the subjective feelings of fatigue or fogginess into an objective understanding of your body’s signals. The purpose of this map is to show you the terrain.

Your personal health journey, however, is the actual voyage. It is unique to you, with your specific genetic makeup, life history, and current circumstances. The principles of hormonal health are universal, but their application is deeply personal. As you move forward, consider this knowledge not as a rigid set of rules, but as a framework for self-discovery.

It is an invitation to become a more astute observer of your own biology, to notice the subtle shifts that occur in response to your actions. This path of self-awareness is the first, and most critical, step toward a truly personalized wellness protocol, one that is built in partnership with informed clinical guidance to help you navigate your unique terrain and reclaim the full potential of your health.

Glossary

endocrine system

hormone production

hpg axis

hormone levels

your endocrine system

chronic stress

growth hormone

cortisol

testosterone levels

anabolic hormones

slow-wave sleep

hpa axis

cortisol levels

glucocorticoid receptors

testosterone biosynthesis