Fundamentals

You feel it in your energy, your sleep, your moods. There is a subtle yet persistent sense that your body’s internal wiring is frayed. This experience, this feeling of being out of sync with your own vitality, is a valid and important signal.

Your body is communicating a disruption in its internal messaging system, the complex and elegant network of hormones that dictates function and feeling. The question of whether your daily choices ∞ the food you consume, the way you move your body ∞ can fundamentally change this internal environment is a profound one.

The answer is an unequivocal yes. These lifestyle inputs are the primary language your endocrine system Meaning ∞ The endocrine system is a network of specialized glands that produce and secrete hormones directly into the bloodstream. understands. They are the raw materials and instructions that can either support or disrupt your biological equilibrium.

To understand this power, we must first understand the messengers themselves. Hormones are chemical molecules that act as signals, traveling through the bloodstream to instruct cells and organs on what to do. Think of them as a postal service, delivering critical instructions that manage everything from your immediate energy levels to your long-term health trajectory.

When this system is balanced, the messages are delivered on time and to the right recipients. When it is unbalanced, messages get lost, delayed, or sent in overwhelming volumes, creating the static and dysfunction you may be experiencing. Diet and exercise Meaning ∞ Diet and exercise collectively refer to the habitual patterns of nutrient consumption and structured physical activity undertaken to maintain or improve physiological function and overall health status. are powerful modulators of this system, capable of turning the volume up or down on these crucial signals.

The Core Metabolic Regulators

Four key hormones are exquisitely sensitive to your daily dietary and activity patterns. Their balance is foundational to metabolic health, and understanding their roles is the first step in reclaiming control over your body’s internal chemistry.

- Insulin is released by the pancreas in response to rising blood glucose, primarily after you eat carbohydrates. Its job is to shuttle glucose out of the bloodstream and into cells for energy or storage. A diet high in processed carbohydrates can lead to a state of insulin resistance, where cells become numb to insulin’s signal.

- Cortisol is your primary stress hormone, produced by the adrenal glands. It follows a natural daily rhythm, peaking in the morning to promote wakefulness and declining at night. Chronic stress, poor sleep, and even certain types of intense exercise can lead to chronically elevated cortisol, disrupting sleep, metabolism, and other hormonal systems.

- Leptin is the satiety hormone, produced by your fat cells. It signals to your brain that you have sufficient energy stores, suppressing appetite. In states of leptin resistance, also common in obesity, the brain fails to receive this “full” signal, leading to persistent hunger despite adequate or excess body fat.

- Ghrelin is the hunger hormone, produced in the stomach. It sends a powerful signal to the brain to stimulate appetite. Its levels naturally rise before meals and fall after eating. The composition of your meals can significantly influence how effectively ghrelin is suppressed.

Your daily choices are a form of biological instruction, continuously shaping your hormonal environment.

These four regulators operate in a tightly coordinated dance. For instance, chronically high cortisol from stress can promote insulin resistance, leading your body to store more fat. This increased body fat then produces more leptin, but the brain becomes resistant to its signal, while ghrelin continues to drive hunger. This creates a vicious cycle of hormonal miscommunication. Lifestyle intervention is the most direct method to interrupt these feedback loops and restore clear communication within your body’s systems.

How Do Diet and Exercise Exert Their Influence?

What you eat and how you move directly impact the production and sensitivity of these hormonal messengers. A diet rich in protein and fiber, for example, is more effective at suppressing ghrelin and promoting satiety than a meal high in refined sugars. This keeps the “hunger” signal quiet for longer.

Regular exercise, particularly resistance training, makes your muscle cells more sensitive to insulin. This means your body needs to produce less insulin to manage blood sugar, reducing the strain on your pancreas and lowering the risk of insulin resistance. These are not small adjustments; they are fundamental shifts in your body’s operating system, initiated by your conscious choices.

| Hormone | Primary Function | Influence of Diet | Influence of Exercise |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin | Manages blood glucose by moving it into cells. | High-glycemic carbohydrates increase insulin secretion. Fiber and protein help moderate this response. | Increases insulin sensitivity in muscle cells, improving glucose uptake. |

| Cortisol | Manages stress, inflammation, and daily energy rhythm. | Diets high in processed foods and sugar can elevate cortisol. A balanced diet can support a healthy cortisol rhythm. | Moderate exercise can lower chronic cortisol. Overtraining can elevate it. |

| Leptin | Signals satiety and energy sufficiency to the brain. | Chronic overeating and obesity can lead to leptin resistance. Anti-inflammatory diets may improve sensitivity. | Regular exercise and fat loss can improve leptin sensitivity over time. |

| Ghrelin | Stimulates appetite and hunger signals. | Protein is highly effective at suppressing ghrelin. Refined carbohydrates are less effective. | Exercise can have short-term suppressive effects on ghrelin. |

The journey to hormonal balance begins with these foundational principles. By focusing on the quality of your food and the consistency of your movement, you are engaging in a direct conversation with your endocrine system. You are providing the clear, consistent signals it needs to restore order and function, moving you from a state of internal static to one of clear, resonant communication.

Intermediate

Recognizing that lifestyle choices influence hormonal signals is the first step. The next is to understand the precise biological mechanisms through which these changes occur. Your body is a system of systems, and the endocrine network is deeply interwoven with your metabolic and nervous systems.

When you intentionally modify your diet or exercise regimen, you are initiating a cascade of biochemical events that recalibrate this intricate network from the cellular level up. This is a process of providing targeted inputs to achieve specific, measurable outputs in your hormonal biomarkers.

For instance, the concept of “insulin sensitivity” moves from an abstract idea to a tangible cellular event. When you engage in resistance training, the mechanical contraction of your muscles triggers the insertion of glucose transporters (specifically GLUT4) into the cell membrane. This process allows glucose to enter the muscle from the bloodstream without requiring high levels of insulin.

This is a direct, non-insulin-mediated pathway for glucose disposal. Over time, consistent training improves the efficiency of the insulin-mediated pathway as well. The result is a body that can manage blood sugar with far less hormonal effort, which has profound downstream effects. Lower insulin levels are associated with reduced inflammation, improved body composition, and a healthier balance of sex hormones.

Strategic Nutritional Interventions for Hormonal Recalibration

Dietary changes can be targeted to influence specific hormonal pathways. The composition of your macronutrients, the timing of your meals, and the inclusion of specific micronutrients all serve as powerful levers.

- Macronutrient Composition The ratio of protein, fats, and carbohydrates in your diet directly influences the hormonal response to a meal. A meal balanced with adequate protein and healthy fats will elicit a much lower insulin spike and a more robust suppression of ghrelin compared to a carbohydrate-dominant meal. This promotes stable energy and appetite control. Diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish, have been shown to lower inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP), which is linked to the development of hormonal resistance syndromes.

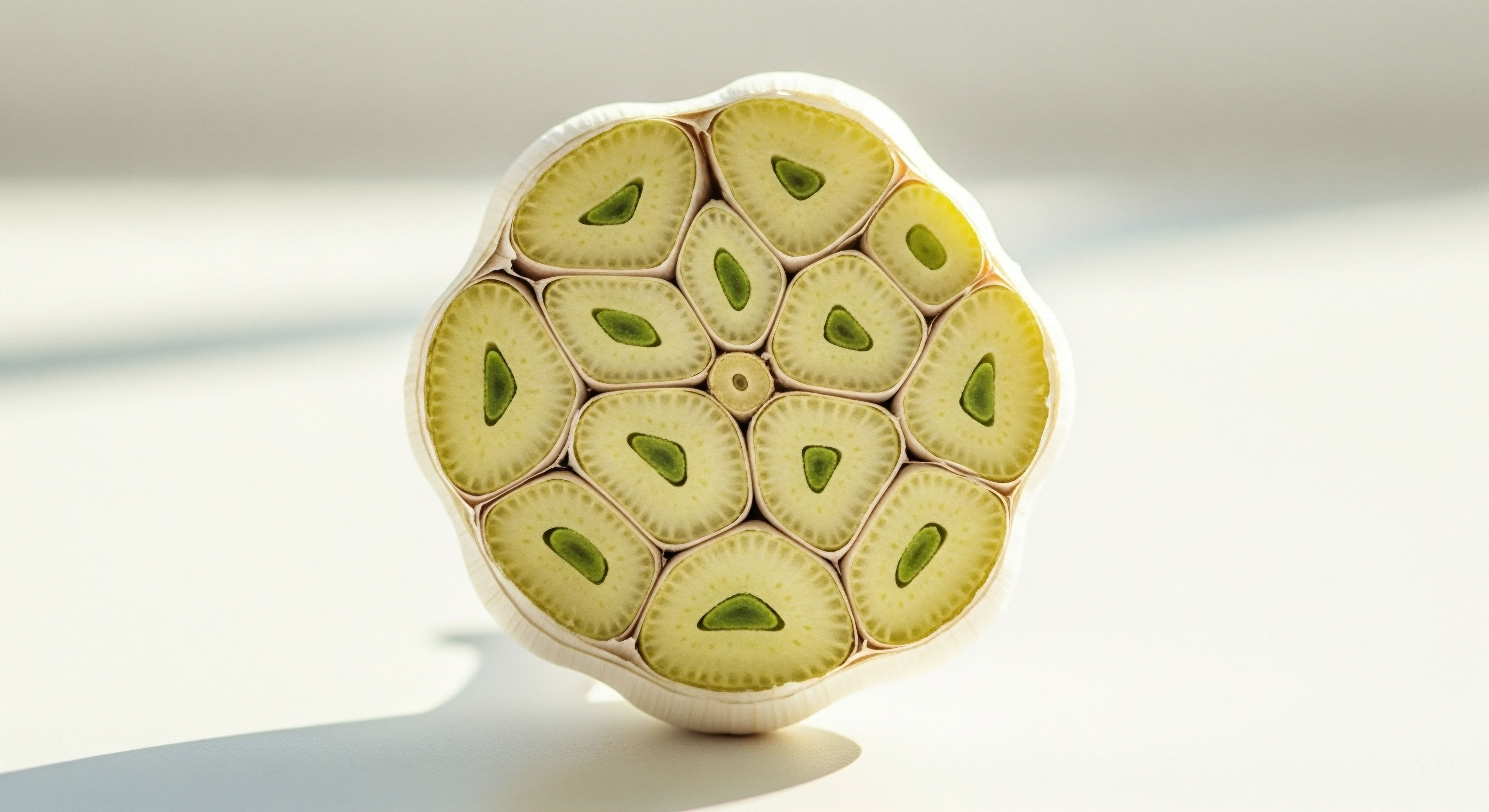

- Fiber’s Role in Detoxification Soluble and insoluble fiber, found in vegetables, legumes, and whole grains, plays a critical role in hormonal health. Fiber slows gastric emptying, which helps to blunt the glucose and insulin response to a meal. It also binds to metabolized estrogens in the digestive tract, facilitating their excretion. This is a crucial pathway for preventing the reabsorption of excess estrogen, a key factor in maintaining a healthy estrogen-to-progesterone balance, particularly for women.

- Micronutrient Co-factors The production of hormones requires specific vitamins and minerals. Thyroid hormone synthesis, for example, is dependent on iodine and selenium. The production of steroid hormones like testosterone and cortisol requires adequate levels of zinc and magnesium. A nutrient-dense diet ensures that the endocrine system has the necessary building blocks to function correctly.

Exercise as a Hormonal Signaling Agent

Different forms of exercise send distinct signals to your endocrine system. A well-rounded physical activity program leverages these different signals to create a comprehensive positive adaptation.

| Exercise Type | Primary Hormonal Effect | Mechanism and Biomarker Change |

|---|---|---|

| Resistance Training | Improves Insulin Sensitivity | Increases GLUT4 transporter expression in muscles, leading to lower fasting insulin and HOMA-IR scores. |

| High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) | Boosts Growth Hormone | The intense metabolic stress stimulates a significant, acute release of human growth hormone (HGH), which aids in fat metabolism and tissue repair. |

| Moderate-Intensity Aerobic Exercise | Lowers Chronic Cortisol | Regular, sustained aerobic activity helps to regulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, lowering resting cortisol levels and improving stress resilience. |

| Restorative Practices (e.g. Yoga, Tai Chi) | Modulates the Stress Response | These practices enhance parasympathetic nervous system tone, which directly counters the “fight-or-flight” sympathetic response, leading to reduced cortisol and adrenaline. |

A strategic combination of diet and exercise does not just influence hormones; it systematically rebuilds the body’s ability to regulate them.

When Lifestyle Is the Foundation for Clinical Protocols

There are circumstances where lifestyle modifications alone may be insufficient to restore optimal function, particularly in cases of significant age-related hormonal decline or specific clinical conditions. In these scenarios, protocols like Testosterone Replacement Therapy Meaning ∞ Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) is a medical treatment for individuals with clinical hypogonadism. (TRT) for men or hormonal optimization for women become necessary interventions.

However, the success of these clinical protocols is dramatically enhanced when built upon a foundation of a healthy lifestyle. A body that is already insulin-sensitive and has low levels of chronic inflammation will respond more effectively and with fewer side effects to hormonal therapies.

For example, in men undergoing TRT, high levels of inflammation can increase the activity of the aromatase enzyme, which converts testosterone into estrogen. By controlling inflammation through diet and exercise, one can optimize the effects of TRT. Similarly, growth hormone Meaning ∞ Growth hormone, or somatotropin, is a peptide hormone synthesized by the anterior pituitary gland, essential for stimulating cellular reproduction, regeneration, and somatic growth. peptide therapies, such as Sermorelin or Ipamorelin, are designed to stimulate the body’s own production of growth hormone.

The efficacy of these peptides is enhanced by deep sleep and stable blood sugar, both of which are direct results of robust lifestyle practices.

The intermediate understanding is this ∞ your choices are a form of conditioning for your endocrine system. You are training it to be more efficient, more responsive, and more resilient. This conditioning creates a biological environment where your body can either heal and balance itself, or become primed for the successful application of advanced clinical support when needed.

Academic

An academic exploration of the relationship between lifestyle and hormonal biomarkers requires a systems-biology perspective, moving beyond the action of a single hormone to examine the dynamic interplay within and between neuroendocrine axes. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, our central stress response system, and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, which governs reproduction and sex hormone production, are two such deeply interconnected systems.

Lifestyle inputs, particularly those related to diet and exercise, act as powerful allostatic modulators, capable of inducing either adaptive or maladaptive plasticity in these critical axes.

Chronic psychological or physiological stress, including that induced by poor dietary habits or excessive, under-recovered exercise, results in sustained activation of the HPA axis. This is characterized by hypersecretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus, leading to increased pituitary release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and subsequent adrenal production of cortisol.

Persistently elevated cortisol has a well-documented suppressive effect on the HPG axis Meaning ∞ The HPG Axis, or Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis, is a fundamental neuroendocrine pathway regulating human reproductive and sexual functions. at multiple levels. It can inhibit the pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, reduce the sensitivity of the pituitary to GnRH, and directly impair gonadal function in both males and females.

The result is a clinically observable decrease in luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and, consequently, testosterone or estradiol production. This represents a clear, mechanistic link between lifestyle-induced stress and gonadal suppression.

Metabolic Endotoxemia and Hormonal Crosstalk

The conversation deepens when we introduce the role of metabolic health, specifically the impact of diet on gut permeability and systemic inflammation. A diet high in saturated fats and refined sugars can alter the gut microbiota and increase intestinal permeability, a condition sometimes referred to as “leaky gut.” This allows lipopolysaccharides (LPS), components of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, to translocate from the gut lumen into systemic circulation. This condition, known as metabolic endotoxemia, is a potent activator of the innate immune system.

LPS binds to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on immune cells like macrophages, triggering a pro-inflammatory cascade and the release of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). These inflammatory cytokines themselves exert suppressive effects on the HPG axis, compounding the effects of elevated cortisol.

Furthermore, this chronic, low-grade inflammation is a primary driver of insulin resistance. Insulin resistance Meaning ∞ Insulin resistance describes a physiological state where target cells, primarily in muscle, fat, and liver, respond poorly to insulin. contributes to a decrease in the hepatic production of sex hormone-binding globulin Meaning ∞ Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin, commonly known as SHBG, is a glycoprotein primarily synthesized in the liver. (SHBG). A reduction in SHBG results in a lower total testosterone level, and while it may transiently increase free testosterone, the overall inflammatory and insulin-resistant state is highly detrimental to hormonal health.

This illustrates a complex interplay where diet composition directly influences gut health, which in turn dictates systemic inflammation, insulin sensitivity, and the functional status of the HPG axis.

The body’s hormonal axes function as an integrated circuit, where a disruption in one pathway, such as metabolic control, inevitably affects others, like gonadal function.

What Is the Impact of Exercise on Neuroendocrine Plasticity?

How does exercise fit into this complex picture? Physical activity is a form of acute physiological stress that, when dosed appropriately, induces beneficial adaptations ∞ a concept known as hormesis. Regular moderate exercise has been shown to improve the negative feedback sensitivity of the HPA axis.

An exercised individual will still mount a cortisol response to a stressor, but the recovery is faster and more efficient, preventing the deleterious effects of chronically elevated cortisol. Resistance training, by increasing skeletal muscle mass, creates a larger reservoir for glucose disposal, directly combating insulin resistance. This improvement in metabolic health Meaning ∞ Metabolic Health signifies the optimal functioning of physiological processes responsible for energy production, utilization, and storage within the body. reduces the inflammatory burden from metabolic endotoxemia Meaning ∞ Metabolic endotoxemia describes chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation. and supports healthy SHBG levels.

The type and intensity of exercise are critical variables. While moderate exercise is restorative, chronic, high-intensity training without adequate recovery can become a maladaptive stressor, suppressing the HPG axis in a manner similar to psychological stress. This is often seen in endurance athletes and is termed “functional hypothalamic amenorrhea” in women and “exercise-hypogonadal male condition” in men. This underscores that exercise is a powerful medicine, and like any medicine, the dose and timing determine its effect.

- Lifestyle Input A diet high in processed foods increases gut permeability, leading to metabolic endotoxemia (elevated LPS).

- Inflammatory Cascade Circulating LPS activates TLR4, triggering the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6).

- HPA Axis Activation Chronic inflammation and psychological stress lead to sustained high levels of cortisol.

- HPG Axis Suppression Both inflammatory cytokines and high cortisol levels inhibit GnRH release from the hypothalamus, suppressing the entire gonadal axis.

- Metabolic Dysfunction Inflammation drives insulin resistance, which in turn lowers SHBG production, further altering sex hormone bioavailability.

In conclusion, the decision to alter diet and exercise is an intervention into a deeply interconnected web of neuroendocrine and metabolic pathways. The changes observed in biomarkers like testosterone, cortisol, and insulin are the surface-level outputs of these deep systemic recalibrations.

A lifestyle founded on a nutrient-dense, anti-inflammatory diet and a balanced exercise program promotes gut integrity, reduces systemic inflammation, improves HPA axis Meaning ∞ The HPA Axis, or Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis, is a fundamental neuroendocrine system orchestrating the body’s adaptive responses to stressors. resilience, and creates the optimal physiological environment for robust HPG axis function. This academic viewpoint reframes lifestyle changes from simple habits to potent, evidence-based modulators of human neuroendocrinology.

References

- Pourghassem Gargari, B. et al. “The effect of diet and/or exercise on ghrelin and leptin levels in obese women.” Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, vol. 16, no. 5, 2011, pp. 648-55.

- Chlebowski, R. T. et al. “Dietary fat reduction and breast cancer outcome ∞ interim efficacy results from the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS).” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 98, no. 24, 2006, pp. 1767-76.

- Irwin, M. L. et al. “Randomized controlled trial of aerobic exercise on body mass index and serum hormones in overweight postmenopausal women.” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 21, no. 3, 2003, pp. 415-22.

- Hill, E. E. et al. “Exercise and circulating cortisol levels ∞ the intensity threshold effect.” Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, vol. 31, no. 7, 2008, pp. 587-91.

- Abdelbasset, W. K. et al. “Aerobic exercise with diet induces hormonal, metabolic, and psychological changes in postmenopausal obese women.” Heliyon, vol. 8, no. 1, 2022, e09165.

- Kallio, J. et al. “Dietary fat and gut microbiota ∞ an experimental study in a human population.” The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, vol. 25, no. 12, 2014, pp. 1261-7.

- Whicker, M. et al. “Exercise and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis in Men ∞ A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Sports Medicine, vol. 49, no. 5, 2019, pp. 753-68.

Reflection

Your Body’s Intrinsic Intelligence

You have now seen the evidence, from foundational concepts to deep physiological mechanisms. The knowledge that your daily actions can sculpt your internal chemistry is a powerful realization. This information is not a set of rigid rules to be followed without thought. It is an invitation to begin a new kind of dialogue with your body.

The symptoms you experience ∞ fatigue, brain fog, metabolic changes ∞ are your body’s attempt to communicate. They are signals rich with information, pointing toward systems that require support.

Consider your own unique context. What messages has your body been sending you? How might the patterns of your daily life be contributing to the conversation? This understanding is the starting point of a personal health investigation. The path forward involves listening to these signals with curiosity and using the principles of nutrition and movement as tools for gentle, consistent course correction.

Your biology has an innate drive toward equilibrium. Your role is to provide the conditions that allow this intelligence to express itself, fostering an environment where vitality is not just a goal, but your natural state.