Fundamentals

The question of whether lifestyle changes alone can reverse osteoporosis touches upon a deeply personal aspect of health ∞ the desire to reclaim control over one’s body through natural, intuitive means. It speaks to a profound yearning to heal from within, using the foundational pillars of nutrition and movement.

Your experience of receiving a diagnosis like osteoporosis is valid, and the instinct to look toward diet and exercise as primary tools is not only understandable but also grounded in solid biological principles. These are, after all, the inputs that have shaped human physiology for millennia.

The feeling that your body’s architectural integrity is compromised can be unsettling. The clinical reality is that for some, particularly those with bone density scores on the cusp of osteoporosis, a dedicated regimen of specific exercises and targeted nutrition can indeed shift the balance back toward osteopenia, a less severe state of bone loss. This represents a reversal of the diagnosis. The journey begins with understanding the living, dynamic nature of your bones.

The Dynamic Skeleton a Constant State of Renewal

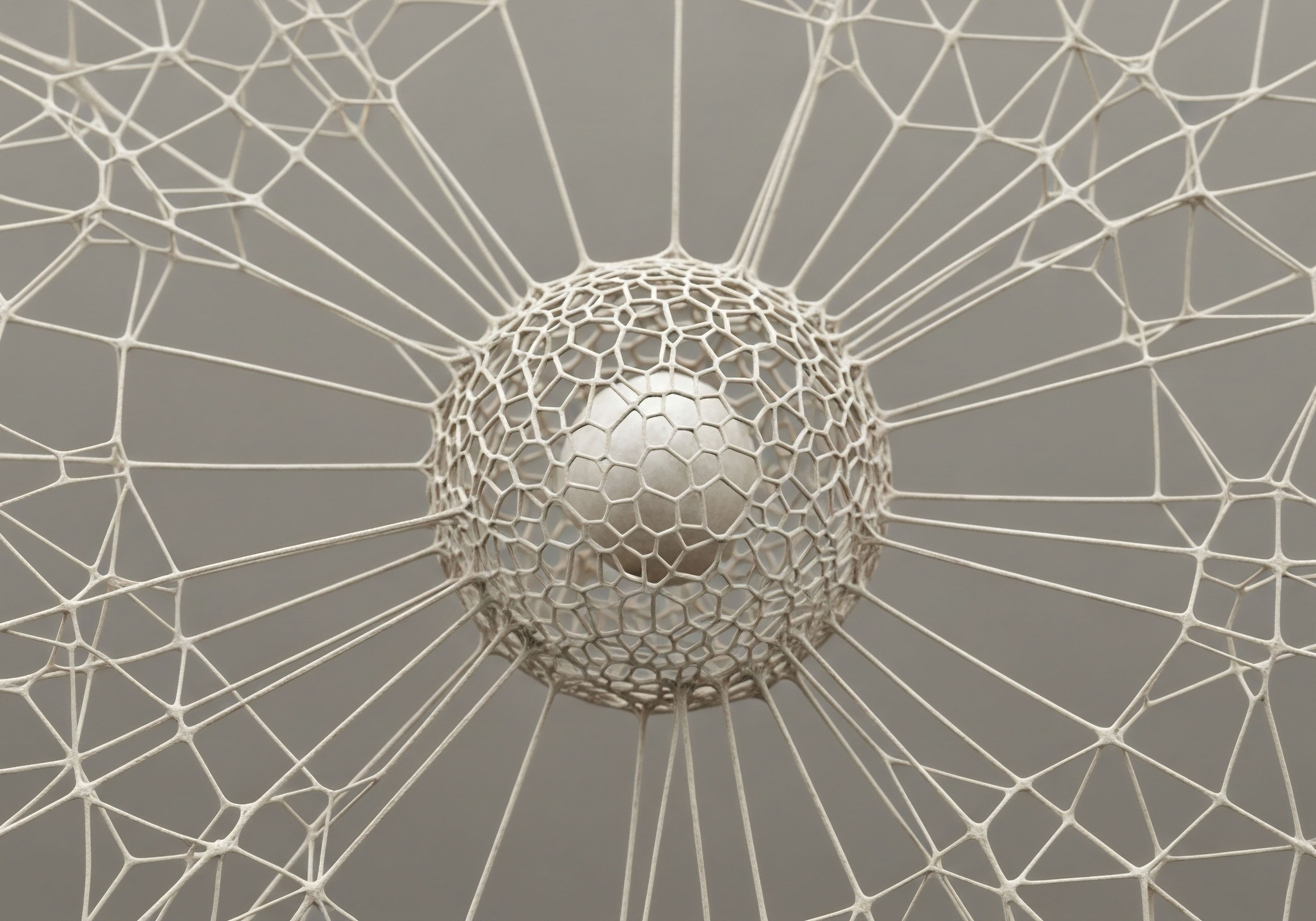

Your skeletal system is a metabolically active organ, constantly undergoing a process called remodeling. Think of it as a meticulous renovation project at the cellular level. Specialized cells called osteoclasts break down old, fatigued bone tissue, while other cells, known as osteoblasts, build new bone to replace it.

This delicate equilibrium ensures your skeleton remains strong and resilient. Osteoporosis occurs when this balance tips, with bone resorption by osteoclasts out-pacing bone formation by osteoblasts. The result is a progressive loss of bone mineral density and a deterioration of its microarchitecture, leaving bones more porous and susceptible to fracture.

The decline in estrogen during menopause is a primary accelerator of this imbalance in women, while in men, a more gradual decline in both testosterone and estrogen contributes to age-related bone loss.

Lifestyle changes form the essential foundation for bone health, capable of slowing bone loss and, in some cases, modestly improving density.

Movement as a Biological Signal

Exercise, specifically weight-bearing and resistance training, is a powerful catalyst for bone health. When you engage in activities like walking, jogging, dancing, or lifting weights, you are sending a direct mechanical signal to your bones. This physical stress is detected by osteocytes, the most abundant bone cells, which then orchestrate the activity of osteoblasts.

The message is clear ∞ this bone is under load and needs to be stronger. Consequently, the osteoblasts are stimulated to lay down new bone tissue, increasing its density and strength over time. This is why exercise is universally recommended as a cornerstone of any osteoporosis management plan. It directly engages the body’s innate capacity for adaptation and renewal.

Nutrition the Building Blocks for Bone

If exercise is the signal for bone construction, nutrition provides the raw materials. Your bones are a reservoir of minerals, primarily calcium and phosphorus, which are essential for their hardness and rigidity. A diet rich in these minerals, along with other key nutrients, is fundamental to supporting bone health.

Vitamin D plays a critical role by facilitating the absorption of calcium from the gut. Without adequate vitamin D, your body cannot effectively utilize the calcium you consume, regardless of the quantity. Other micronutrients, including magnesium, vitamin K, and protein, also contribute to the complex matrix that gives bone its structure and resilience. Therefore, a well-formulated nutritional strategy is an indispensable component of supporting your skeletal framework.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding of diet and exercise, a more granular examination of specific protocols reveals the mechanics of how these interventions influence bone metabolism. While lifestyle modifications are crucial, their efficacy in reversing osteoporosis is often a matter of degree, dependent on the severity of bone loss and the individual’s underlying hormonal environment.

For those with mild osteoporosis or osteopenia, a precisely targeted lifestyle program can be sufficient to halt bone loss and, in some instances, achieve modest gains in bone mineral density. However, for individuals with more significant bone loss, these strategies become part of a comprehensive approach that may also include pharmacological support.

Crafting an Anabolic Exercise Protocol

To elicit a bone-building response, an exercise regimen must meet certain criteria. The principle of progressive overload is paramount; the mechanical stress placed on the bones must be gradually increased over time to continue stimulating adaptation. A well-rounded program incorporates multiple forms of exercise:

- Weight-Bearing Aerobic Exercise This includes activities where your bones and muscles work against gravity. While low-impact exercises like walking are beneficial for overall health, high-impact activities, if appropriate for the individual, are more effective at stimulating bone formation. Examples include jogging, dancing, and stair climbing.

- Resistance Training This form of exercise involves moving your body against some type of resistance, such as weights, resistance bands, or your own body weight. Strength training is particularly effective because it creates localized stress on the bones at the points where muscles attach, directly signaling the need for reinforcement in those areas.

- Balance and Postural Exercises Activities like Tai Chi and yoga are important for improving proprioception, coordination, and muscle strength, which collectively reduce the risk of falls ∞ the primary cause of fractures in individuals with osteoporosis.

The goal of these exercises is to create a mechanical environment that favors the activity of osteoblasts, the cells responsible for synthesizing new bone matrix.

Nutritional Synergy for Skeletal Health

A diet optimized for bone health extends beyond simply ensuring adequate calcium and vitamin D intake. It involves a synergistic interplay of various nutrients that support the entire bone remodeling process. The table below outlines key nutrients and their roles:

| Nutrient | Role in Bone Health | Dietary Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium | Primary mineral component of bone, providing rigidity and strength. | Dairy products, fortified plant-based milks, leafy greens (kale, collards), sardines, tofu. |

| Vitamin D | Essential for calcium absorption from the intestine and its incorporation into bone. | Sunlight exposure, fatty fish (salmon, mackerel), fortified foods, egg yolks. |

| Magnesium | Contributes to the structural development of bone and is involved in the regulation of calcium transport. | Nuts, seeds, whole grains, legumes, dark chocolate, leafy green vegetables. |

| Vitamin K | Activates proteins involved in bone mineralization and helps bind calcium to the bone matrix. | Leafy green vegetables (spinach, kale, broccoli), natto, prunes. |

| Protein | Forms the collagen framework of bone, providing flexibility and absorbing impact. | Lean meats, poultry, fish, eggs, dairy, legumes, soy products. |

What Are the Limits of Lifestyle Interventions?

The primary limitation of relying solely on diet and exercise to reverse osteoporosis is the powerful influence of the endocrine system. In postmenopausal women, the sharp decline in estrogen production removes a critical restraint on osteoclast activity. Estrogen helps to suppress the rate of bone resorption.

Without it, osteoclasts become more numerous and active, leading to an accelerated rate of bone loss that is difficult to counteract with lifestyle measures alone. While exercise and nutrition can help to mitigate this loss and support bone formation, they often cannot fully compensate for the profound shift in the hormonal landscape.

Studies have shown that even rigorous exercise programs typically result in modest bone density increases of 1-2%. This is beneficial but may not be sufficient to move someone with a T-score of -3.5 back into the osteopenic range.

Academic

A deep-dive into the cellular and molecular underpinnings of bone physiology reveals the intricate interplay between mechanical loading, nutritional substrates, and hormonal signaling. The question of whether lifestyle changes can reverse osteoporosis without hormonal intervention is, from a biochemical perspective, a question of whether non-hormonal anabolic stimuli can overcome a systemic catabolic environment driven by hormonal deficiencies.

The answer lies in the quantitative and qualitative capacity of these stimuli to influence the bone remodeling unit (BRU), the temporary anatomical structure where bone resorption and formation occur.

The Mechanostat Theory and Bone Adaptation

The response of bone to mechanical loading is elegantly described by the Mechanostat Theory, proposed by Harold Frost. This theory posits that bone adapts its mass and architecture to the peak strains engendered by daily activities. When mechanical strains fall below a certain genetically determined threshold, bone is removed.

When strains exceed this threshold, bone is added. Exercise, particularly high-impact and resistance training, is a method of intentionally creating strains that surpass this modeling threshold, thereby stimulating a net anabolic effect. The process is mediated by osteocytes, which act as mechanosensors. They translate mechanical forces into biochemical signals that regulate the recruitment and activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. However, the sensitivity of the mechanostat itself is modulated by systemic factors, including hormones.

The efficacy of exercise in stimulating bone formation is directly influenced by the prevailing hormonal milieu, particularly the levels of estrogen and testosterone.

Hormonal Regulation of Bone Remodeling

The endocrine system exerts profound control over bone metabolism. Estrogen, for instance, plays a crucial role in maintaining bone homeostasis in both sexes. It promotes the apoptosis (programmed cell death) of osteoclasts and suppresses the production of RANKL (Receptor Activator of Nuclear factor Kappa-B Ligand), a key cytokine that promotes osteoclast formation and activation.

The precipitous drop in estrogen during menopause leads to a surge in RANKL, unleashing osteoclast activity and initiating a period of rapid bone loss. Testosterone also supports bone health, primarily through its aromatization to estrogen in bone tissue and by directly stimulating osteoblast proliferation and differentiation.

The following table details the effects of key hormones on bone cells:

| Hormone | Effect on Osteoblasts (Formation) | Effect on Osteoclasts (Resorption) |

|---|---|---|

| Estrogen | Promotes survival and activity. | Inhibits activity and promotes apoptosis. |

| Testosterone | Directly stimulates proliferation and differentiation; indirectly via aromatization to estrogen. | Inhibits activity, primarily through its conversion to estrogen. |

| Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) | Intermittent exposure is anabolic. | Continuous high levels are catabolic, stimulating resorption. |

| Growth Hormone / IGF-1 | Stimulates proliferation and collagen synthesis. | Indirectly stimulates resorption through its effects on PTH. |

Why Is Hormonal Intervention Often Necessary?

In a state of significant hormonal deficiency, such as postmenopause or andropause, the systemic environment becomes overwhelmingly catabolic for bone. The loss of estrogen’s restraining influence on osteoclasts creates a state of high bone turnover where resorption far outpaces formation.

While exercise can increase the anabolic signals to osteoblasts, it is often fighting an uphill battle against a powerful, system-wide catabolic drive. This is why pharmacological interventions, including hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and other antiresorptive or anabolic agents, are frequently necessary for individuals with established osteoporosis.

These therapies work by directly addressing the underlying imbalance ∞ HRT by restoring the hormonal brake on osteoclast activity, and other drugs by either potently inhibiting resorption (e.g. bisphosphonates, denosumab) or directly stimulating formation (e.g. teriparatide). Lifestyle changes remain a critical adjunct to these therapies, enhancing their efficacy and contributing to overall musculoskeletal health, but they cannot single-handedly replicate the profound systemic effects of hormonal regulation.

References

- LeBoff, M. S. et al. “The clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis.” Osteoporosis International, vol. 33, no. 10, 2022, pp. 2049-2102.

- Cosman, F. et al. “Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis.” Osteoporosis International, vol. 25, no. 10, 2014, pp. 2359-81.

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. “Osteoporosis.” National Institutes of Health, 2023.

- Brooke-Wavell, K. et al. “Strong, steady and straight ∞ an expert consensus statement on physical activity and exercise for osteoporosis.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 56, no. 15, 2022, pp. 837-846.

- Daly, R. M. et al. “Exercise for the prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women ∞ an evidence-based guide to the optimal prescription.” Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy, vol. 23, no. 2, 2019, pp. 170-180.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Personal Health Equation

You have now seen the evidence, from the foundational principles of movement and nutrition to the complex cellular ballet directed by your endocrine system. The information presented here is designed to be a map, illustrating the known terrain of bone health. Your personal journey, however, will be unique.

Understanding the biological mechanisms at play is the first, most powerful step toward proactive engagement with your health. It shifts the perspective from one of passive diagnosis to one of active partnership with your own physiology. As you consider your next steps, reflect on how these systems interact within you.

The path forward involves a thoughtful calibration of these inputs, tailored to your specific biology, history, and goals. This knowledge is your starting point for a more informed conversation about your long-term wellness.