Fundamentals

You feel it as a subtle but undeniable shift in your body’s internal climate. The energy that once felt abundant now seems to have a shorter half-life. The sleep that used to be restorative can feel unfulfilling. These are not isolated events; they are signals from a biological system undergoing a profound recalibration.

Your body is communicating a change in its core operating instructions, a change centered within your endocrine system. This journey is about learning to interpret that language, not as a sign of decline, but as an invitation to consciously participate in your own well-being. The conversation about a woman’s heart health is a conversation about hormonal architecture.

For decades, the hormone estrogen acts as a primary guardian of your cardiovascular system. It is a powerful signaling molecule that instructs your blood vessels to remain flexible and open. It manages the conversation between your liver and your bloodstream, ensuring cholesterol is processed efficiently. Estrogen helps maintain a low-inflammation environment, which is the physiological foundation of a healthy heart. Its presence is a constant, steadying influence on the intricate functions that support cardiovascular resilience.

The experience of hormonal transition is your body signaling a fundamental change in its operational blueprint, directly impacting heart health.

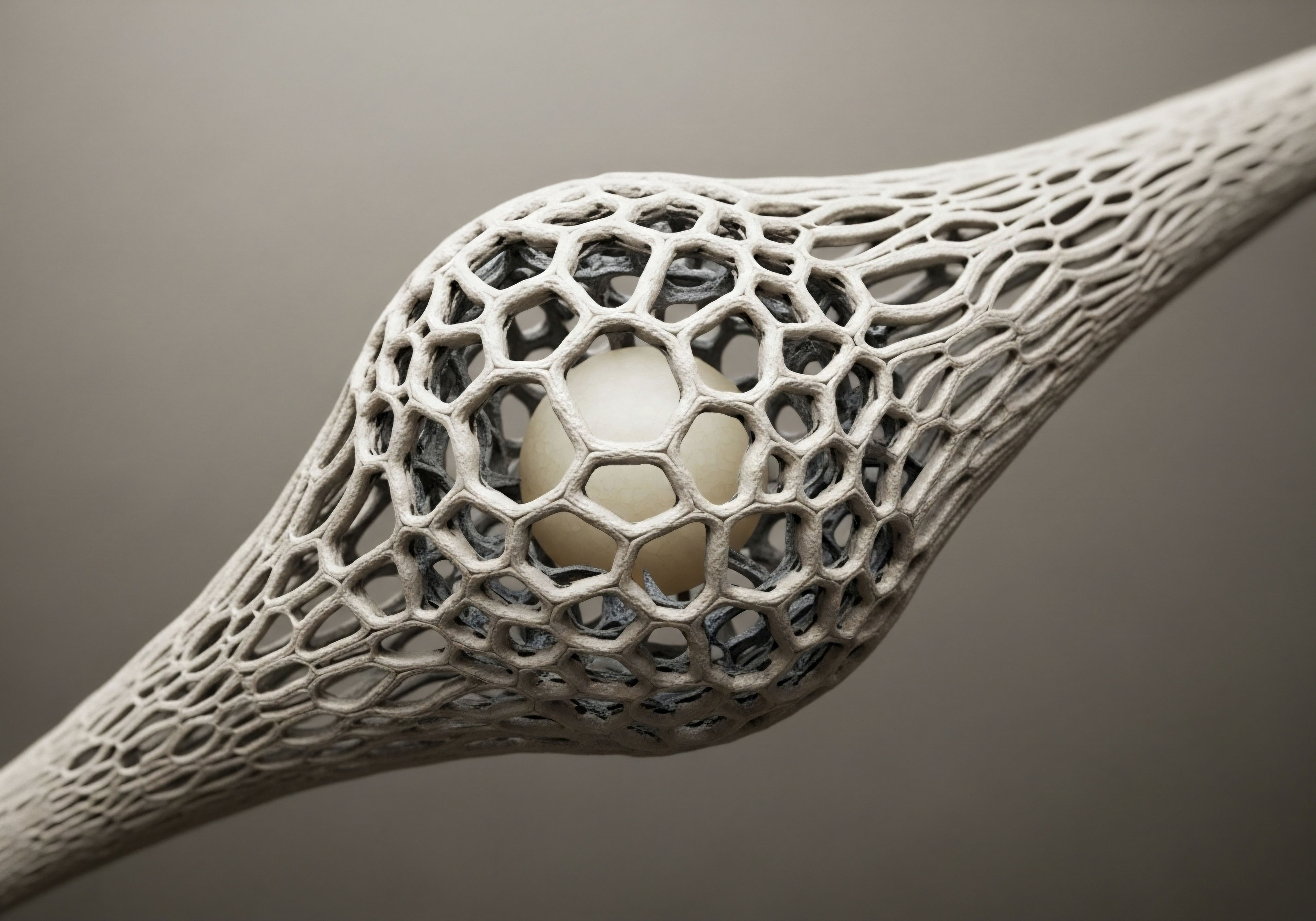

The transition of perimenopause and menopause marks a planned, natural decline in estrogen production. This is a significant architectural change. With less estrogen to direct operations, the biological environment shifts. Blood vessels may become stiffer. The liver’s ability to clear certain types of cholesterol from the blood can become less efficient, leading to changes in your lipid profile.

The body’s baseline level of inflammation can rise. These are the direct, biological consequences of a changing hormonal landscape, and they are the mechanisms that link this life transition to an altered risk profile for cardiovascular health. Understanding this process is the first step toward intervening intelligently.

The Cardiovascular System under Estrogen’s Influence

To appreciate the shift, one must first understand the baseline state. During a woman’s reproductive years, estrogen is a master regulator of cardiovascular homeostasis. It accomplishes this through several parallel pathways, creating a multi-layered shield of protection.

Vasodilation and Blood Flow

Estrogen directly promotes the production of nitric oxide, a potent vasodilator. This molecule signals the smooth muscles in artery walls to relax, which widens the vessels. This action lowers blood pressure and ensures that oxygen-rich blood flows freely to the heart muscle and all other tissues. This inherent flexibility is a hallmark of a youthful, responsive vascular system.

Lipid Metabolism

The hormone has a favorable effect on cholesterol levels. It works within the liver to increase the number of receptors for LDL (low-density lipoprotein), often called “bad cholesterol.” With more receptors, the liver can more effectively pull LDL particles out of circulation, keeping blood levels low. Concurrently, estrogen tends to increase levels of HDL (high-density lipoprotein), the “good cholesterol” that helps transport cholesterol away from the arteries.

What Changes during the Menopausal Transition?

As ovarian production of estrogen wanes, these protective mechanisms are systematically downregulated. This is not a failure of the system; it is a programmed adaptation. The body is transitioning to a new metabolic state. However, this new state requires a different set of inputs and supports to maintain cardiovascular wellness.

The reduction in nitric oxide production can lead to less flexible arteries and a gradual increase in blood pressure. The liver becomes less adept at clearing LDL cholesterol, which is why many women notice their lipid panels changing in their late 40s and 50s, even without significant changes to their diet.

This creates an internal environment where the building blocks of arterial plaque are more readily available. The challenge, and the opportunity, lies in using lifestyle as a tool to counteract these systemic shifts and provide the support the body now requires.

Intermediate

Recognizing the biological shifts that accompany hormonal change is the foundational step. The next is to take deliberate action. The human body is a dynamic system, constantly responding to the signals it receives from its environment. Lifestyle choices are a powerful form of biological communication.

Through nutrition, movement, stress modulation, and restorative sleep, you can send new instructions to your cells, effectively creating a buffer against the cardiovascular risks associated with lower estrogen levels. This is about building a robust biological scaffolding that supports the heart and vasculature when the original hormonal architecture has been altered.

Nutritional Recalibration a Cellular Dialogue

The food you consume is information. Every meal provides the raw materials and the instructional codes that influence your body’s inflammatory status, insulin sensitivity, and lipid metabolism. During the menopausal transition, the body becomes less forgiving of metabolic insults. A diet high in refined carbohydrates and processed fats can accelerate the very risks that estrogen decline initiates. Conversely, a nutrient-dense, anti-inflammatory diet can directly counteract them.

The Power of Phytonutrients and Fiber

Plants produce a vast array of compounds called phytonutrients, many of which have powerful biological effects. Lignans, found in flaxseeds, and isoflavones, in soy, are phytoestrogens. These plant-based molecules can bind to estrogen receptors in the body, exerting a weak, modulatory effect that can help buffer some of the changes from estrogen loss.

Soluble fiber, abundant in oats, barley, apples, and beans, is also a critical tool. It binds to cholesterol in the digestive tract, preventing its reabsorption and helping to lower LDL levels. Insoluble fiber supports a healthy gut microbiome, which is intimately linked to systemic inflammation and metabolic health.

A targeted lifestyle strategy provides the body with the precise inputs needed to manage lipids, inflammation, and insulin sensitivity after estrogen’s protective influence wanes.

The table below contrasts two dietary approaches, illustrating how specific food choices translate into distinct biological signals for the cardiovascular system.

| Dietary Component | Standard Western Diet Signal | Hormone-Supportive Diet Signal |

|---|---|---|

| Fats |

High in saturated and trans fats (processed foods, red meat). This promotes inflammation and increases LDL cholesterol. |

Rich in monounsaturated (olive oil, avocado) and omega-3 fats (fatty fish, walnuts). These signals reduce inflammation and support healthy lipid profiles. |

| Carbohydrates |

High in refined sugars and flours (white bread, pastries, sugary drinks). This causes rapid blood sugar spikes, promoting insulin resistance. |

High in complex carbohydrates and fiber (vegetables, legumes, whole grains). This ensures a slow release of glucose, promoting insulin sensitivity. |

| Protein |

Often centered on processed meats. Can be inflammatory and lack micronutrients. |

Sourced from lean poultry, fish, legumes, and tofu. Provides essential amino acids for muscle maintenance and supports satiety, aiding weight management. |

| Micronutrients |

Typically low in vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients due to high levels of processing. |

Abundant in antioxidants and phytonutrients from a wide variety of colorful plants. These compounds directly combat oxidative stress in the blood vessels. |

Movement as Endocrine Medicine

Physical activity is a non-negotiable component of cardiovascular health, particularly during and after the menopausal transition. Exercise works on multiple levels to counteract hormonal impacts. It improves insulin sensitivity, helps manage weight, strengthens the heart muscle, and reduces stress.

- Resistance Training ∞ Lifting weights or using resistance bands builds and maintains muscle mass. Muscle is a highly metabolic tissue that acts as a “glucose sink,” pulling sugar from the bloodstream and reducing the burden on the pancreas to produce insulin. This directly fights the trend toward insulin resistance that can accompany menopause.

- Aerobic Exercise ∞ Activities like brisk walking, running, or cycling challenge the heart and lungs. This type of exercise improves the heart’s efficiency, lowers resting heart rate and blood pressure, and promotes the growth of new blood vessels. It also improves endothelial function, the health of the inner lining of your arteries.

- High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) ∞ Short bursts of intense effort followed by brief recovery periods can provide significant cardiovascular benefits in a shorter amount of time. HIIT is particularly effective at improving VO2 max, a key indicator of cardiovascular fitness and longevity.

How Can I Manage Stress and Sleep for Heart Health?

The connection between chronic stress, poor sleep, and heart disease is mediated by the hormone cortisol. Elevated cortisol disrupts sleep, increases blood sugar, raises blood pressure, and promotes the storage of visceral fat around the organs. This type of fat is metabolically active and secretes inflammatory molecules, creating a vicious cycle of stress and cardiovascular risk.

Prioritizing sleep hygiene and implementing stress-reduction techniques are direct physiological interventions. They work by lowering cortisol and activating the parasympathetic nervous system, the body’s “rest and digest” state. This allows the heart and blood vessels to recover and repair.

Academic

The increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in postmenopausal women is a complex phenomenon rooted in the intersection of endocrinology and vascular biology. While the general decline in estrogen is widely acknowledged, a deeper, systems-level analysis reveals a cascade of interconnected molecular events.

The primary focus of this academic exploration is the specific mechanism of postmenopausal atherogenic dyslipidemia, with a secondary look at its synergistic relationship with insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction. This provides a coherent, mechanistic narrative explaining the shift from a protected to a vulnerable cardiovascular phenotype.

Estrogen Receptor Signaling and Hepatic Lipid Metabolism

The cardioprotective effects of estrogen are mediated primarily through its binding to two nuclear hormone receptors ∞ Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα) and Estrogen Receptor Beta (ERβ). In the context of lipid metabolism, ERα signaling within the liver is paramount. 17β-estradiol (E2), the most potent endogenous estrogen, acts as a ligand for ERα in hepatocytes. This binding event initiates a transcriptional cascade that directly upregulates the gene for the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR).

The LDLR is responsible for recognizing and internalizing apolipoprotein B (ApoB)-containing lipoproteins, primarily LDL, from the circulation. An increase in LDLR expression on the hepatocyte surface leads to enhanced clearance of LDL cholesterol from the blood. The decline of E2 during menopause results in reduced ERα activation in the liver.

This transcriptional downregulation of the LDLR gene leads to a lower density of LDL receptors, decreased LDL clearance, and consequently, a rise in circulating LDL cholesterol concentrations. This is a core mechanism behind the quantitative shift in the lipid profile observed in menopausal women.

Beyond LDL Quantity the Issue of Particle Quality

The menopausal transition also affects the qualitative nature of lipoproteins. The emerging insulin resistance characteristic of this period, driven by changes in body composition and hormonal signaling, promotes an increase in hepatic VLDL (very-low-density lipoprotein) secretion.

In an insulin-resistant state, increased flux of free fatty acids to the liver, combined with de novo lipogenesis, results in the production of large, triglyceride-rich VLDL particles. Through the action of cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), these triglycerides are exchanged for cholesteryl esters in LDL and HDL particles.

This process generates small, dense LDL (sdLDL) particles and lipid-depleted HDL. Small, dense LDL particles are particularly atherogenic due to their enhanced ability to penetrate the arterial endothelium and their higher susceptibility to oxidative modification.

The menopausal transition initiates a cascade of molecular events, beginning with reduced estrogen receptor activation in the liver and culminating in an atherogenic lipid profile and vascular inflammation.

The Convergence of Dyslipidemia, Inflammation, and Endothelial Dysfunction

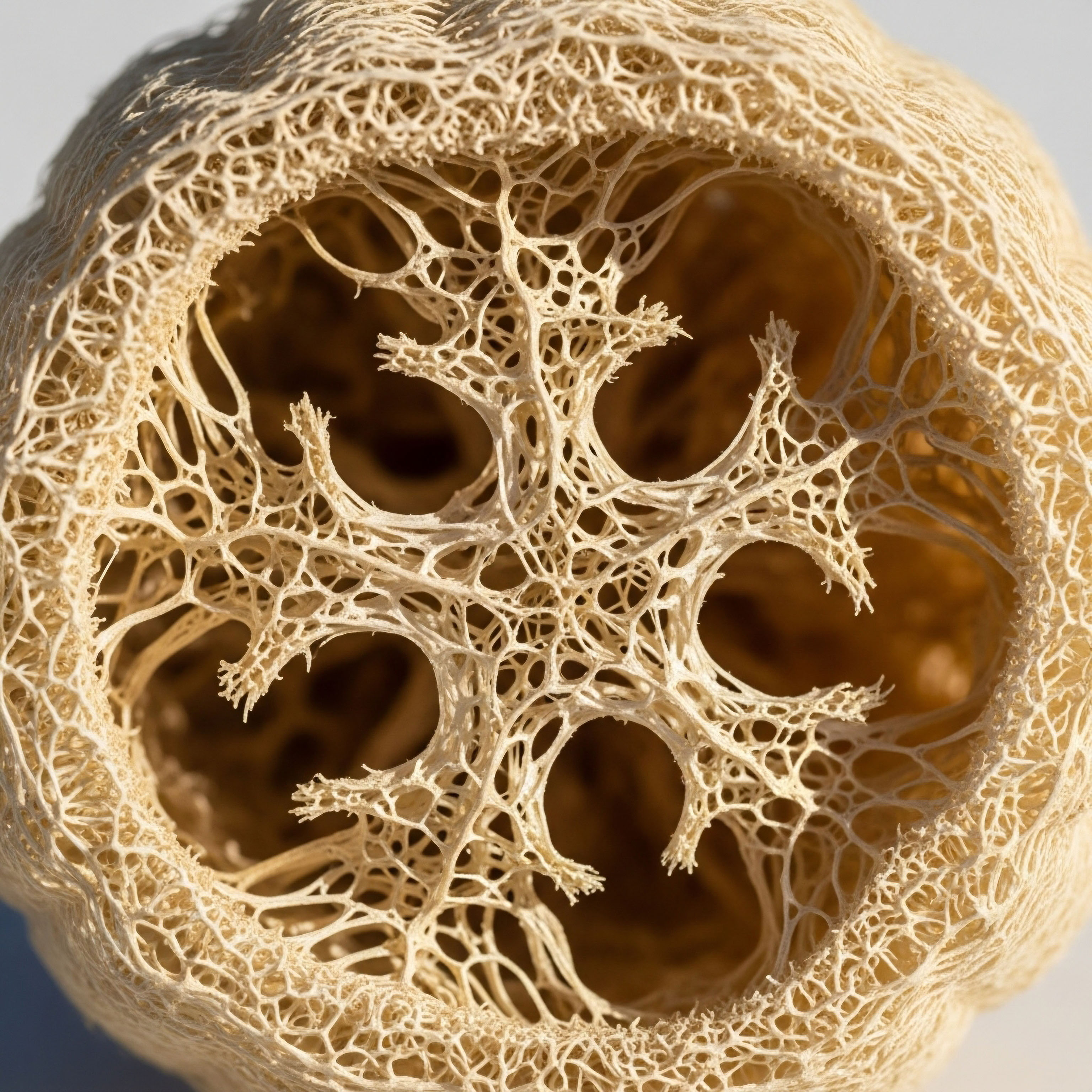

These hormonal and metabolic changes do not occur in isolation. They converge at the level of the blood vessel wall, specifically the endothelium. The endothelium is a single layer of cells lining the arteries that acts as a critical signaling interface.

A healthy endothelium, under the influence of estrogen, produces nitric oxide (NO), a key anti-atherosclerotic molecule. NO maintains vasodilation, inhibits platelet aggregation, and suppresses the expression of adhesion molecules that recruit inflammatory cells to the artery wall. Estrogen promotes NO production by upregulating endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), the enzyme responsible for its synthesis.

With the loss of estrogen, eNOS activity declines. Simultaneously, the increase in circulating sdLDL and the low-grade chronic inflammation driven by visceral adipose tissue and gut dysbiosis contribute to a state of endothelial dysfunction. Oxidized LDL particles directly inhibit eNOS function and promote the expression of adhesion molecules like VCAM-1 and ICAM-1.

This makes the endothelium “sticky,” facilitating the infiltration of monocytes into the subendothelial space, a foundational event in the formation of atherosclerotic plaque. The table below details key biomarkers that reflect this complex pathophysiology.

| Biomarker | Biological Significance in Menopausal Transition | Lifestyle Intervention Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) |

Measures the total number of atherogenic particles (VLDL, IDL, LDL). It is a more accurate predictor of CVD risk than LDL-C alone, as it reflects the particle concentration. |

Reduced by diets low in refined carbohydrates and saturated fats. Increased intake of soluble fiber also helps lower ApoB. |

| hs-CRP (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein) |

A sensitive marker of systemic inflammation. Elevated levels indicate an inflammatory state that promotes all stages of atherosclerosis. |

Lowered by regular exercise, stress management, adequate sleep, and an anti-inflammatory diet rich in omega-3s and antioxidants. |

| Lp(a) (Lipoprotein(a)) |

A genetically determined lipoprotein that is both atherogenic and prothrombotic. Estrogen is known to suppress Lp(a) levels, so they may rise during menopause. |

While largely genetic, some evidence suggests that intense lifestyle changes can have a modest impact. The primary management is awareness of risk. |

| Fasting Insulin & HOMA-IR |

Direct measures of insulin resistance. Elevated levels indicate the body is struggling to manage glucose, a state linked to dyslipidemia and endothelial dysfunction. |

Strongly improved by resistance training, weight management, and a low-glycemic diet. This is a highly modifiable risk factor. |

Why Does Visceral Fat Accumulate More Easily after Menopause?

The preferential deposition of fat in the abdominal region (visceral adipose tissue or VAT) is another hallmark of the menopausal metabolic shift. This is also hormonally driven. Estrogen influences the expression of enzymes and receptors in adipose tissue, favoring fat storage in the subcutaneous depots of the hips and thighs. Androgens, which are present in women and become more dominant as estrogen declines, promote visceral fat accumulation.

VAT is a metabolically active organ that functions as an endocrine gland in its own right. It secretes a host of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, and adipokines like resistin, which further exacerbate insulin resistance.

This creates a self-perpetuating cycle where hormonal changes lead to VAT accumulation, and VAT, in turn, worsens the metabolic and inflammatory environment, accelerating cardiovascular risk. Lifestyle interventions, particularly exercise and caloric management, are exceptionally effective at reducing VAT, directly breaking this cycle.

References

- Mendelsohn, Michael E. and Richard H. Karas. “The protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system.” New England Journal of Medicine 340.23 (1999) ∞ 1801-1811.

- Matthews, Karen A. et al. “Changes in cardiovascular risk factors during the perimenopause and postmenopause and carotid artery atherosclerosis in healthy women.” Stroke 32.5 (2001) ∞ 1104-1111.

- Carr, M. C. “The emergence of the metabolic syndrome with menopause.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 88.6 (2003) ∞ 2404-2411.

- Lovejoy, J. C. et al. “Increased visceral fat and decreased energy expenditure during the menopausal transition.” International journal of obesity 32.6 (2008) ∞ 949-958.

- Rosano, G. M. C. et al. “Menopause and cardiovascular disease ∞ the evidence.” Climacteric 10.sup1 (2007) ∞ 19-24.

- St-Onge, Marie-Pierre, et al. “Sleep duration and quality ∞ impact on lifestyle behaviors and cardiometabolic health.” Current cardiology reports 18.5 (2016) ∞ 1-9.

- Estruch, Ramón, et al. “Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet.” New England journal of medicine 368.14 (2013) ∞ 1279-1290.

- Krauss, Ronald M. et al. “AHA Dietary Guidelines ∞ revision 2000 ∞ A statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association.” Circulation 102.18 (2000) ∞ 2284-2299.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a biological and strategic framework for understanding your body’s evolving needs. The science provides a map, detailing the terrain of your internal world and identifying the pathways that lead toward sustained vitality. Yet, a map is only a guide. The true journey is yours to walk.

It begins with listening to the signals your body is already sending. The fatigue, the changes in sleep, the subtle shifts in how you feel after a meal ∞ these are all points of data. They are your body’s request for a different kind of support.

Consider the knowledge you now have as a new lens through which to view your daily choices. When you choose whole, unprocessed foods, you are not just eating; you are providing the precise molecular information your cells need to quell inflammation.

When you engage in movement that feels both challenging and restorative, you are not just exercising; you are instructing your muscles to become more efficient at managing energy and your heart to become more resilient. When you protect your sleep and find moments of stillness, you are actively downregulating the chemistry of stress that can silently tax your cardiovascular system.

This path is one of partnership with your own physiology. It is a shift away from seeing your body as something that is failing and toward seeing it as a responsive, adaptable system that is ready to work with you. What is one small, deliberate choice you can make today to begin that conversation?