Fundamentals

The feeling is unmistakable. It is a subtle yet persistent sense that the internal wiring of your own body is operating from a script you no longer recognize. Perhaps it manifests as a fatigue that sleep does not mend, a new difficulty in managing your weight, or a shift in your mood and resilience that feels foreign.

This experience, this disconnect, is a valid and important signal. Your body is communicating a change in its internal environment. The question of whether lifestyle choices can correct hormonal imbalances begins with acknowledging the profound truth that your daily actions are a constant conversation with your endocrine system. These choices are the language you use to instruct the vast, silent network of glands and molecules that regulate your vitality.

Hormones are chemical messengers that travel through your bloodstream to tissues and organs, carrying precise instructions that dictate nearly every aspect of your physical and emotional life. They control your metabolism, your sleep-wake cycles, your reproductive function, and your capacity to handle stress.

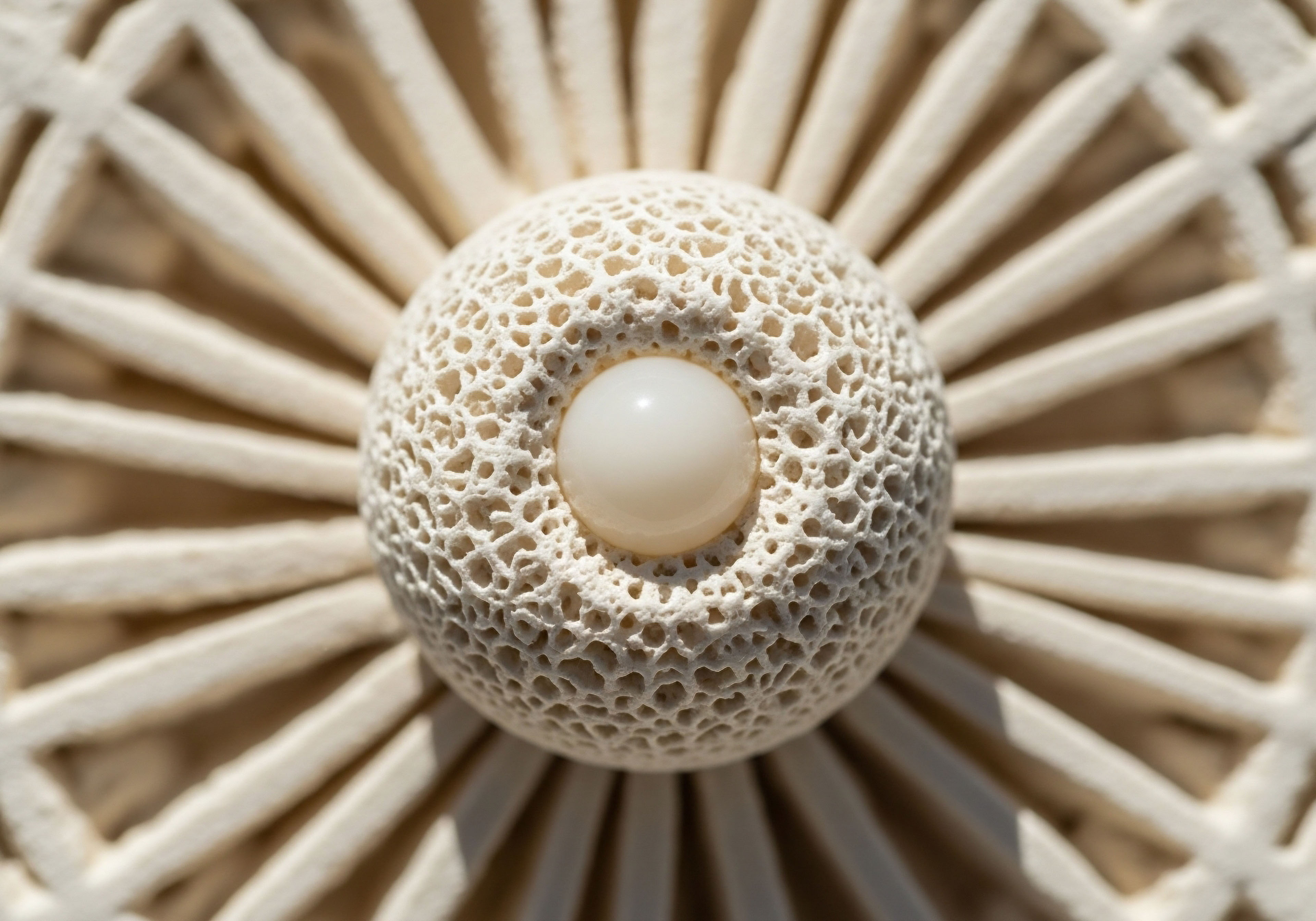

This entire network, the endocrine system, operates on a sophisticated system of feedback loops, much like a thermostat maintains a room’s temperature. When one hormone level rises or falls, it signals other glands to adjust their own production, creating a state of dynamic equilibrium. Lifestyle inputs are the primary external factors that can either support or disrupt this delicate balance. They are not merely passive influences; they are active participants in your body’s biochemical dialogue.

Your daily choices are a constant, powerful conversation with the intricate network of your endocrine system.

The Foundational Inputs

Understanding how to guide your hormonal health begins with three core pillars of lifestyle ∞ nutrition, physical activity, and restorative processes like sleep and stress modulation. Each one provides a unique set of signals that your body translates into hormonal responses. These are the levers you can access to begin recalibrating your internal systems.

Viewing them as distinct, isolated factors is a common misstep. Their power lies in their synergy, as the information from each one compounds and influences the others, creating a unified message that either promotes balance or perpetuates dysfunction.

Nutrition the Building Blocks of Balance

The food you consume provides the fundamental raw materials for hormone production. Steroid hormones, including cortisol, estrogen, and testosterone, are synthesized from cholesterol, a molecule derived from dietary fats. Without an adequate supply of healthy fats, the very foundation of these critical hormones is compromised.

Proteins are broken down into amino acids, which are the precursors for thyroid hormones and peptide hormones like insulin. Carbohydrates, in turn, have a powerful influence on insulin secretion, a master hormone that affects nearly every other hormonal pathway in the body.

A diet rich in nutrient-dense whole foods delivers the vitamins and minerals, such as zinc, magnesium, and selenium, that act as cofactors in the enzymatic reactions that build and activate these messengers. The quality of your diet directly informs the structural integrity and functional capacity of your entire endocrine system.

Physical Activity a Catalyst for Communication

Movement is a potent hormonal modulator. When you engage in physical activity, you are sending powerful signals to your cells. Resistance training, for instance, can increase cellular sensitivity to insulin, meaning your body needs to produce less of it to manage blood sugar effectively.

This improvement in insulin sensitivity is a cornerstone of metabolic and hormonal health. Exercise also influences the production of anabolic hormones like testosterone and growth hormone, which are vital for maintaining muscle mass, bone density, and metabolic rate. Simultaneously, consistent and appropriate physical activity helps regulate the output of stress hormones like cortisol, improving your body’s overall resilience to stressors.

The type, intensity, and duration of exercise all contribute to a unique hormonal signature, making it a highly adaptable tool for targeted adjustments.

How Does Your Daily Routine Speak to Your Endocrine System?

Your body does not distinguish between different sources of stress. A demanding job, a poor night’s sleep, or a diet high in processed foods can all trigger the same physiological stress response. This response is governed by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which culminates in the release of cortisol.

While essential for short-term survival, chronic activation of this system can lead to widespread hormonal disruption. Elevated cortisol can suppress thyroid function, impair sex hormone production, and contribute to insulin resistance. Restorative practices are the counterbalance to this activation. Deep, consistent sleep is when your body repairs tissue, consolidates memory, and regulates the daily rhythm of cortisol release.

Without sufficient sleep, this rhythm becomes dysregulated, setting the stage for systemic imbalance. Managing stress through practices like mindfulness, time in nature, or focused breathing exercises sends a direct signal to the HPA axis to downregulate, fostering an internal environment conducive to hormonal harmony.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding of lifestyle inputs requires an appreciation for the intricate regulatory systems that govern hormonal communication. The body’s endocrine function is organized around several key axes, which are complex feedback loops connecting the brain to various glands. These axes function as the command-and-control centers for hormonal output.

When lifestyle factors create sustained disruption, these systems can become dysregulated, leading to the symptoms of hormonal imbalance. Correcting this imbalance through lifestyle modification involves sending consistent, corrective signals to these specific regulatory pathways, encouraging them to return to a state of optimal function.

The Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal Axis

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis is the central nervous system’s interface with the endocrine system, governing the body’s response to stress. When a stressor is perceived, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which signals the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

ACTH then travels to the adrenal glands and stimulates the production of cortisol. In a healthy system, rising cortisol levels send a negative feedback signal back to the hypothalamus and pituitary, shutting down the stress response. Chronic stressors, whether psychological, inflammatory, or metabolic, can impair this feedback mechanism.

The system can become stuck in an “on” position, leading to persistently elevated cortisol, or it can become exhausted, resulting in an inadequate cortisol response. Both states have profound consequences, disrupting sleep cycles, suppressing immune function, and altering the function of other hormonal axes.

Targeted lifestyle strategies can directly modulate the body’s central stress response system, recalibrating cortisol output and restoring systemic balance.

Lifestyle interventions can directly modulate HPA axis function. For example, a diet that stabilizes blood sugar by emphasizing fiber, protein, and healthy fats prevents the glycemic volatility that is itself a potent HPA axis activator. Regular, moderate exercise has been shown to improve the resilience of the HPA axis, while chronic, high-intensity training without adequate recovery can exacerbate its dysfunction.

Restorative practices are particularly potent here. Sleep hygiene is paramount, as the majority of HPA axis regulation occurs during the sleep cycle. Mindfulness and meditation practices have been clinically demonstrated to reduce the perception of stress, thereby decreasing the initial activation signal from the hypothalamus.

Can Specific Dietary Strategies Target Hormonal Pathways?

Dietary composition sends specific biochemical instructions to the body. A high-protein diet, for instance, can enhance satiety signaling through hormones like glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY), while also providing the necessary amino acids for thyroid hormone synthesis. The composition of dietary fats is also critical.

Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish, walnuts, and flaxseeds, are precursors to anti-inflammatory molecules called resolvins and protectins. By reducing systemic inflammation, they can improve the sensitivity of hormone receptors throughout the body, including those for insulin and thyroid hormone. Conversely, a diet high in processed industrial seed oils rich in omega-6 fatty acids can promote an inflammatory state that interferes with this signaling.

The following table illustrates how different types of physical activity can produce distinct hormonal responses, allowing for a tailored approach to exercise based on individual goals and hormonal status.

| Exercise Type | Primary Hormonal Response | Physiological Outcome | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance Training | Increases testosterone, growth hormone (GH), and insulin sensitivity. | Promotes muscle growth, increases metabolic rate, improves glucose uptake by muscles. | Requires adequate protein intake and recovery time for optimal anabolic effects. |

| High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) | Significant post-exercise increase in GH and catecholamines (epinephrine, norepinephrine). | Enhances fat oxidation, improves cardiovascular efficiency, potent stimulus for mitochondrial biogenesis. | Can be a significant stressor; must be balanced with adequate recovery to avoid HPA axis dysregulation. |

| Moderate Aerobic Exercise | Improves insulin sensitivity, can help regulate cortisol levels, releases endorphins. | Enhances cardiovascular health, improves mood, builds endurance. | Long-duration, high-intensity endurance training can chronically elevate cortisol and suppress gonadal function. |

| Yoga and Mindful Movement | Decreases cortisol, increases GABA (an inhibitory neurotransmitter). | Reduces perceived stress, activates the parasympathetic nervous system (“rest and digest”). | Focuses on recovery and nervous system regulation, complementing more intense forms of exercise. |

The Role of Micronutrients in Endocrine Function

While macronutrients provide the building blocks, micronutrients are the essential catalysts for hormonal processes. They function as cofactors for the enzymes that drive the synthesis and conversion of hormones. Without adequate levels of these key vitamins and minerals, endocrine pathways can become sluggish and inefficient. Lifestyle choices, particularly dietary patterns, are the primary determinants of micronutrient status.

- Zinc ∞ This mineral is crucial for the production of testosterone and plays a significant role in the synthesis and secretion of insulin. It is also necessary for the proper functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis.

- Magnesium ∞ Involved in over 300 enzymatic reactions, magnesium is vital for blood glucose control, blood pressure regulation, and HPA axis modulation. It can improve insulin sensitivity and has a calming effect on the nervous system.

- Selenium ∞ This trace mineral is essential for thyroid health, as it is a required cofactor for the enzyme that converts the inactive thyroid hormone T4 into the active form T3.

- B Vitamins ∞ The family of B vitamins, particularly B6, B9 (folate), and B12, are critical for methylation processes, which are necessary for metabolizing and detoxifying hormones, especially estrogens.

Academic

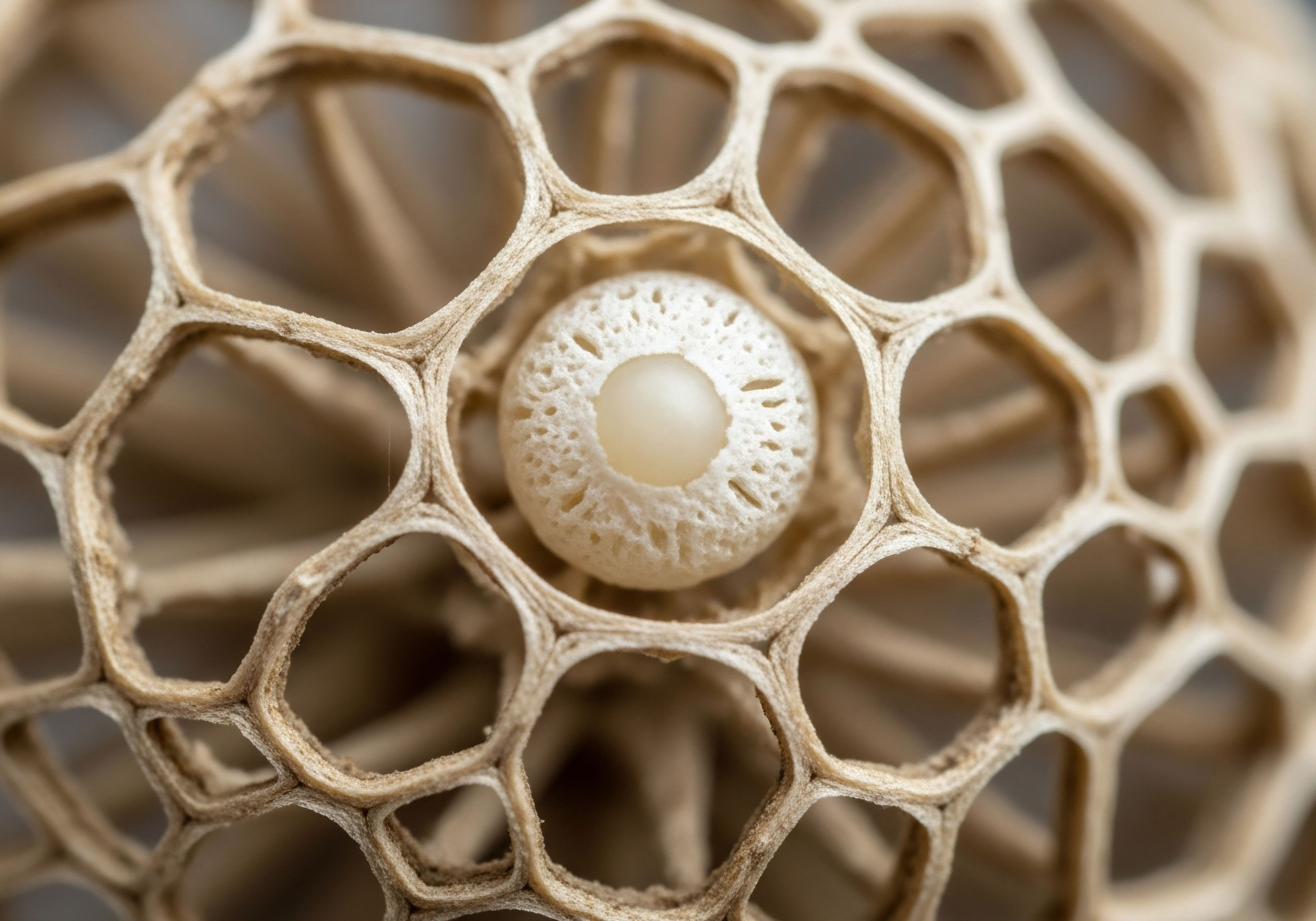

A sophisticated examination of hormonal regulation through lifestyle must extend into the complex interplay between the gut microbiome and the host endocrine system. The community of microorganisms residing in the human gastrointestinal tract is now understood to function as a veritable endocrine organ in its own right.

This microbial ecosystem actively synthesizes, metabolizes, and modulates a wide array of host hormones and neurotransmitters, exerting systemic influence on metabolic health, immune function, and neuro-hormonal axes. The composition and metabolic output of the gut microbiome are exquisitely sensitive to dietary inputs, positioning it as a primary mechanistic link between nutrition and systemic hormonal balance.

The Gut Microbiome an Endocrine Regulator

The gut-hormone axis operates through several interconnected pathways. Gut microbes directly participate in the regulation of steroid hormones through their enzymatic activity. A key example is the “estrobolome,” a collection of bacterial genes whose protein products are capable of metabolizing estrogens.

These bacterial enzymes, such as β-glucuronidase, can deconjugate estrogens that have been inactivated by the liver and excreted into the gut via bile. This deconjugation reactivates the estrogens, allowing them to be reabsorbed into circulation. An imbalance in the estrobolome, or dysbiosis, can therefore lead to either a deficiency or an excess of circulating estrogens, contributing to conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, and estrogen-receptor-positive cancers.

Furthermore, the microbiome modulates the production of gut-derived hormones that regulate appetite and glucose homeostasis. The fermentation of dietary fibers by specific bacterial phyla, such as Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, propionate, and acetate. These SCFAs act as signaling molecules.

Butyrate serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes, maintaining the integrity of the gut barrier. Both butyrate and propionate stimulate the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY) from intestinal L-cells. These hormones enhance insulin secretion from the pancreas, slow gastric emptying, and promote satiety by signaling to the hypothalamus, thereby playing a central role in metabolic regulation.

The metabolic activity of the gut microbiome directly influences systemic hormonal balance, acting as a critical mediator between diet and endocrine health.

What Is the Role of the Gut Microbiome in Systemic Endocrine Regulation?

The integrity of the intestinal barrier is paramount for endocrine stability. A diet low in fiber and high in processed foods, along with chronic stress, can compromise this barrier, leading to increased intestinal permeability. This allows bacterial components, most notably lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, to translocate from the gut lumen into systemic circulation.

This condition, known as metabolic endotoxemia, triggers a potent pro-inflammatory response. The resulting low-grade chronic inflammation is a powerful disruptor of endocrine function. It directly contributes to insulin resistance by interfering with insulin receptor signaling in peripheral tissues. It can also impair thyroid function by inhibiting the conversion of T4 to T3 and downregulating thyroid receptor expression. This inflammatory signaling also activates the HPA axis, perpetuating a cycle of stress and hormonal dysregulation.

The following table details specific microbial actions and their documented effects on host hormonal pathways, illustrating the gut’s profound influence on systemic health.

| Microbial Action | Key Microbes Involved | Hormonal Consequence | Systemic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCFA Production | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia, Bifidobacterium | Increased GLP-1 and PYY secretion. | Improved insulin sensitivity, enhanced satiety, reduced appetite. |

| Estrogen Metabolism | Bacteria possessing β-glucuronidase/β-glucosidase enzymes (e.g. certain Clostridia species). | Modulation of circulating estrogen levels. | Influences risk for estrogen-sensitive conditions and regulates menstrual cycle. |

| GABA Synthesis | Lactobacillus spp. Bifidobacterium spp. | Increased availability of GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter. | Modulation of the HPA axis, reduction in anxiety-like behaviors. |

| Tryptophan Metabolism | Clostridium sporogenes, Ruminococcus spp. | Conversion of tryptophan to serotonin precursors or kynurenine pathway metabolites. | Influences mood via serotonin and modulates immune response via the kynurenine pathway. |

Therapeutic Lifestyle Interventions Targeting the Gut Hormone Axis

Given this intricate relationship, lifestyle strategies aimed at shaping the microbiome represent a highly targeted approach to correcting hormonal imbalances. The primary tool for this is diet. A diet rich in diverse sources of fermentable fibers ∞ from vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains ∞ provides the necessary substrate for SCFA-producing bacteria. This directly supports gut barrier integrity and promotes favorable metabolic signaling.

- Fiber Fermentation ∞ Ingested dietary fibers, which are indigestible by human enzymes, arrive in the colon intact.

- Microbial Metabolism ∞ Specific bacterial species ferment these fibers, producing SCFAs such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate as metabolic byproducts.

- L-Cell Stimulation ∞ Butyrate and propionate bind to G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) like GPR41 and GPR43 on the surface of enteroendocrine L-cells.

- Hormone Secretion ∞ This binding event triggers the release of GLP-1 and PYY into circulation.

- Systemic Signaling ∞ GLP-1 travels to the pancreas to enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion, while both hormones signal to the brain to induce feelings of fullness, thereby regulating food intake and energy balance.

In addition to fiber, the inclusion of polyphenol-rich foods (like berries, dark chocolate, and green tea) and fermented foods containing live cultures (like yogurt, kefir, and sauerkraut) can further enhance microbial diversity and support anti-inflammatory pathways. These dietary strategies, combined with stress management techniques that reduce HPA-axis-driven gut permeability, form a cohesive and scientifically grounded protocol for correcting hormonal imbalances by targeting their root origins within the gastrointestinal system.

References

- Hills, Ronald D. et al. “Gut Microbiome ∞ Profound Implications for Diet and Disease.” Nutrients, vol. 11, no. 7, 2019, p. 1613.

- Weigle, David S. et al. “A high-protein diet induces sustained reductions in appetite, ad libitum caloric intake, and body weight despite compensatory changes in diurnal plasma leptin and ghrelin concentrations.” The American journal of clinical nutrition, vol. 82, no. 1, 2005, pp. 41-48.

- Varghese, Monisha, et al. “Hormonal and Metabolic Changes of Aging and the Influence of Lifestyle Modifications.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 102, no. 11, 2017, pp. 4317-4326.

- Salehzadeh, Fahimeh, et al. “The effect of exercise and nutrition on hormonal and metabolic responses.” Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, vol. 19, no. 1, 2020, pp. 569-580.

- Qi, Xue, et al. “The impact of the gut microbiota on the reproductive and maternal health.” Reproductive Sciences, vol. 28, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1-12.

- Karl, J. Philip, et al. “Effects of psychological, environmental and physical stressors on the gut microbiota.” Frontiers in microbiology, vol. 9, 2018, p. 2013.

- Martin, Corby K. et al. “Effect of calorie restriction on resting metabolic rate and spontaneous physical activity.” Obesity, vol. 15, no. 12, 2007, pp. 2964-2973.

Reflection

Your Biology Is a Story

You have now traveled through the complex, interconnected world of your own internal chemistry. You have seen how the food on your plate, the movement of your body, and the quiet moments of rest are not passive events but active instructions that write the next chapter of your health.

The information presented here is a map, showing the pathways and connections that govern your vitality. It is a powerful tool for understanding the language your body speaks. Yet, a map is not the territory. Your unique biology, genetics, and life history create a landscape that is yours alone.

The true work begins now, in the thoughtful application of this knowledge to your own life. It is a process of self-study, of listening to the signals your body sends in response to the changes you make. This journey toward balance is a personal one, and understanding the science is the first, most empowering step toward navigating it with intention and confidence.

Glossary

your endocrine system

endocrine system

physical activity

insulin sensitivity

anabolic hormones

hpa axis

lifestyle interventions

thyroid hormone

fatty acids

gut microbiome

gut-hormone axis

estrobolome

short-chain fatty acids