Fundamentals

You feel it before you can name it. A subtle shift in the background rhythm of your own biology. The energy that once felt abundant now seems rationed. Sleep, which used to be a reliable refuge, might offer less restoration. The mental clarity you took for granted is now subject to static and interference.

This experience, this lived reality of change, is the starting point of our entire conversation. It is a deeply personal and valid perception of a profound biological process. The question of whether lifestyle adjustments alone can address the symptoms of hormonal decline is a valid and pressing one. The answer begins with understanding the intricate communication network operating within you this very moment.

Your body is governed by a series of elegant feedback loops, a constant conversation between your brain and your endocrine glands. The primary dialogue for reproductive and metabolic health is orchestrated by the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Imagine the hypothalamus in your brain as the mission commander, sending strategic signals to the pituitary gland, the field general.

The pituitary, in turn, dispatches specific hormonal troops ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) ∞ to the gonads (the testes in men, the ovaries in women). These glands then produce the hormones that define much of our vitality ∞ testosterone and estrogen. This entire system is designed for self-regulation.

The circulating levels of testosterone and estrogen are monitored by the brain, which then adjusts its signals to maintain a precise balance. Hormonal decline is the gradual fraying of this communication line. The signals may weaken, or the glands may become less responsive. The result is a system slowly losing its equilibrium, and you feel the consequences of that instability.

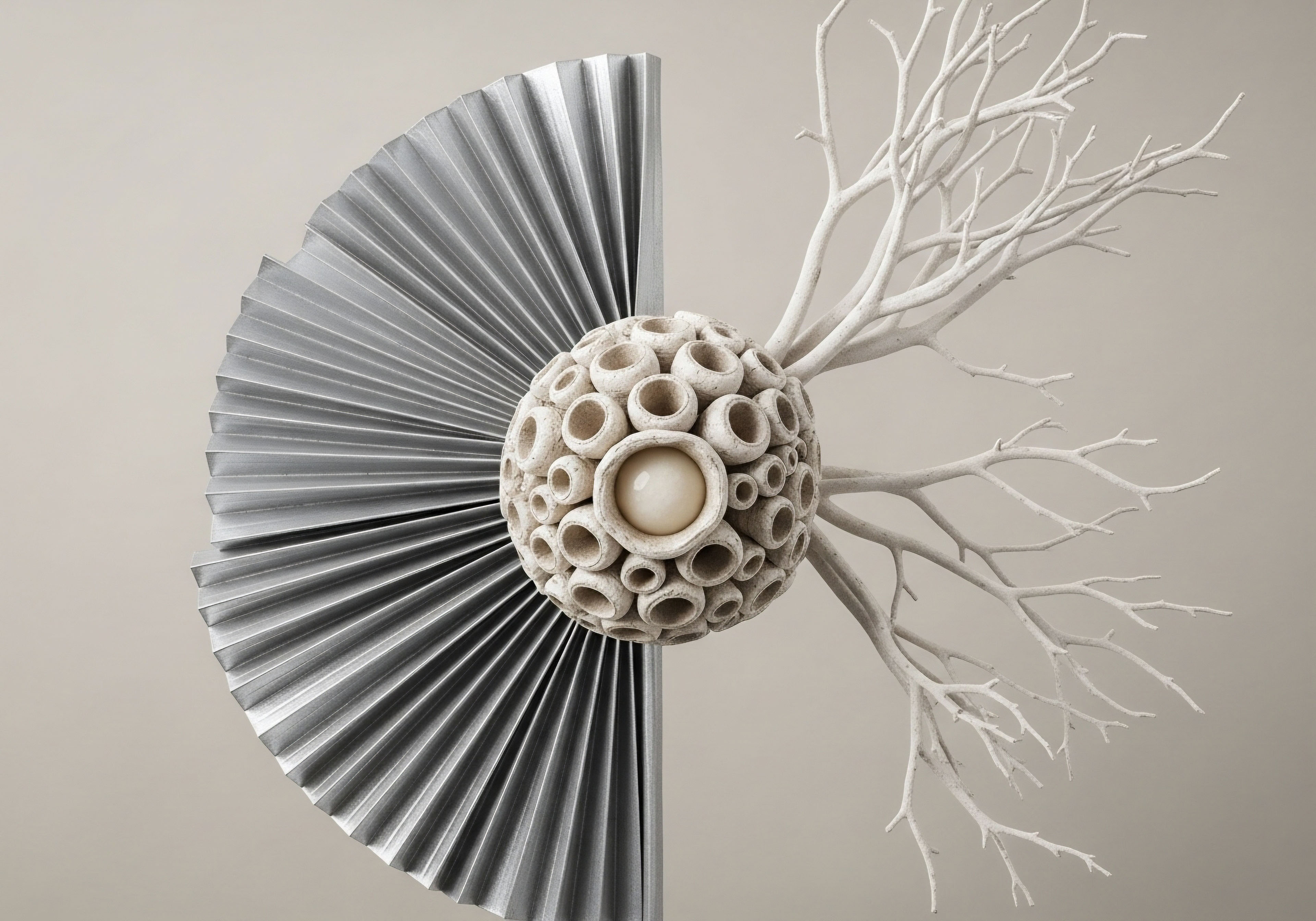

The body’s internal hormonal symphony is a dynamic interplay of signals and responses, and symptoms arise when this communication network loses its precision.

The Nature of Hormonal Messengers

Hormones themselves are sophisticated biochemical messengers. They are molecules that travel through the bloodstream to target cells throughout the body, from your brain to your bones to your skin. Upon arrival, a hormone binds to a specific receptor on or inside a cell, much like a key fitting into a lock.

This binding action initiates a cascade of events within the cell, instructing it to perform a specific job ∞ to burn fat, to build muscle, to regulate mood, or to manage inflammation. Estrogen, for instance, has receptors in over 300 different tissues, which explains its far-reaching effects on everything from cognitive function to skin elasticity.

Testosterone is equally vital for both sexes, contributing to lean muscle mass, bone density, motivation, and libido. When the production of these key messengers wanes, countless cellular processes are left without clear instructions, leading to the systemic symptoms many experience as aging.

What Is the Timeline of Endocrine Decline?

The process of hormonal change is a gradual and staggered phenomenon, occurring over decades. It does not happen all at once; different hormonal systems may decline at different rates, a concept that gives us a more complete picture of the aging process. This staggered decline involves several key phases:

- Adrenopause ∞ Often beginning in a person’s late 20s or early 30s, this phase is characterized by a slow reduction in the production of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) by the adrenal glands. DHEA is a precursor hormone that the body can convert into other hormones, including testosterone and estrogen. Its decline contributes to a subtle decrease in overall resilience and energy.

- Somatopause ∞ This refers to the age-related decline in Growth Hormone (GH) and its key mediator, Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1). This process also begins in early adulthood and accelerates after the age of 30. GH is released in pulses, primarily during deep sleep, and is fundamental for cellular repair, tissue regeneration, maintaining lean body mass, and regulating metabolism. A reduction in GH contributes to changes in body composition, such as increased body fat and decreased muscle mass, as well as reduced recovery capacity.

- Menopause and Andropause ∞ These are the most well-known phases of hormonal decline. In women, perimenopause can begin in the late 30s or 40s, marked by fluctuating estrogen and progesterone levels, leading to the eventual cessation of menstruation, known as menopause. In men, andropause is a more gradual process, with testosterone levels typically declining by about 1-2% per year after the age of 30. This slow but steady reduction can lead to symptoms like fatigue, low libido, reduced muscle mass, and mood changes.

Understanding this timeline reveals that hormonal decline is a long-term biological process. The symptoms that become apparent in mid-life are often the culmination of changes that began years or even decades earlier. This perspective frames lifestyle intervention as a proactive, long-term strategy for supporting the body’s intrinsic hormonal architecture.

By focusing on nutrition, exercise, sleep, and stress management, we are providing the foundational support that these complex endocrine systems require to function optimally for as long as possible. These interventions aim to improve the body’s internal environment, enhancing both the production of hormones and the sensitivity of the cells that receive their signals. The goal is to fortify the entire communication network, making it more resilient to the inevitable changes of age.

Intermediate

The capacity of lifestyle changes to meaningfully resolve symptoms of hormonal decline rests on a deep, physiological principle ∞ your endocrine system is exquisitely sensitive to its environment. The foods you consume, the ways you move your body, the quality of your sleep, and the stress you manage are all potent inputs that directly influence hormonal synthesis, transport, and receptor sensitivity.

This section moves from the ‘what’ of hormonal decline to the ‘how’ of intervention, examining the specific, evidence-based lifestyle protocols that can recalibrate your body’s internal signaling environment. We will investigate the mechanisms through which these strategies work, providing a blueprint for building a resilient physiological foundation.

Nutritional Biochemistry as a Hormonal Lever

Nutrition provides the raw materials for hormone production. The architecture of your diet directly influences the availability of precursors for steroid hormones like testosterone and estrogen, as well as the peptide hormones that govern metabolism. A sophisticated nutritional strategy goes beyond simple calorie counting; it focuses on providing the specific biochemical building blocks the endocrine system needs to function.

Macronutrients the Foundational Building Blocks

The balance of proteins, fats, and carbohydrates in your diet creates the metabolic backdrop for hormone production. Each macronutrient plays a distinct and essential role.

- Dietary Fats ∞ Cholesterol is the parent molecule from which all steroid hormones ∞ including DHEA, testosterone, and estrogen ∞ are synthesized. A diet critically low in healthy fats can starve the body of this essential precursor. Incorporating sources of monounsaturated fats (avocados, olive oil), polyunsaturated fats (nuts, seeds, fatty fish), and even some saturated fats (from quality animal sources or coconut oil) is necessary for robust hormone production.

- Proteins ∞ Amino acids, the building blocks of protein, are required for the creation of peptide hormones like insulin and growth hormone. They are also essential for building and maintaining muscle tissue, which is a key endocrine organ in itself, influencing insulin sensitivity and metabolic rate. Adequate protein intake signals to the body that it is in an anabolic (building) state, which supports healthy hormonal profiles.

- Carbohydrates ∞ Carbohydrates play a key role in regulating cortisol and thyroid hormone function. While excessive intake of refined carbohydrates can disrupt insulin signaling, strategic consumption of complex, fiber-rich carbohydrates can help lower stress hormones and support the conversion of inactive thyroid hormone (T4) to the active form (T3), which is crucial for metabolic rate.

Micronutrients the Biochemical Spark Plugs

If macronutrients are the building blocks, micronutrients are the skilled laborers and catalysts that make construction possible. Many vitamins and minerals act as essential cofactors in the enzymatic pathways of hormone synthesis and metabolism. Deficiencies in these key areas can create significant bottlenecks in the endocrine production line.

| Micronutrient | Role in Endocrine Function | Dietary Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc | Essential for the production of testosterone and for the proper functioning of the HPG axis. It is also involved in thyroid hormone production. | Oysters, beef, pumpkin seeds, lentils, shiitake mushrooms. |

| Magnesium | Plays a role in regulating the HPA axis and managing cortisol levels. It also improves insulin sensitivity and is involved in the synthesis of steroid hormones. | Dark leafy greens, almonds, avocados, dark chocolate, pumpkin seeds. |

| Vitamin D | Functions as a pro-hormone and has been shown to correlate positively with testosterone levels in men. It is vital for immune function and insulin regulation. | Sunlight exposure, fatty fish (salmon, mackerel), fortified milk, egg yolks. |

| B Vitamins | A complex of vitamins (especially B5 and B6) that are critical for adrenal function, stress management, and the synthesis and clearance of estrogen. | Meat, poultry, fish, eggs, legumes, nutritional yeast, leafy greens. |

| Selenium | A crucial component of the enzyme that converts inactive T4 to active T3 thyroid hormone, making it central to metabolic health. | Brazil nuts, tuna, sardines, beef, turkey, eggs. |

Movement as Endocrine Medicine

Physical activity is one of the most powerful modulators of the human endocrine system. Different types of exercise elicit distinct hormonal responses, allowing for a targeted approach to addressing specific symptoms of decline. The goal is to create a weekly movement routine that provides the right signals for muscle growth, metabolic efficiency, and stress reduction.

Targeted exercise protocols act as a direct stimulus to the endocrine system, capable of influencing hormone production and improving cellular sensitivity to their messages.

Resistance Training Building More than Muscle

Resistance training, such as weightlifting, is a potent stimulus for an anabolic hormonal environment. The mechanical stress placed on muscles during heavy lifting triggers a cascade of responses designed to repair and build tissue. This process has profound endocrine effects.

An acute bout of heavy resistance exercise, particularly involving large muscle groups, has been shown to transiently increase levels of both testosterone and growth hormone. This response is part of the body’s adaptive mechanism to increase muscle protein synthesis. Over the long term, consistent resistance training increases the number and sensitivity of androgen receptors in muscle cells.

This means the body becomes more efficient at utilizing the testosterone it has. Furthermore, building and maintaining lean muscle mass improves insulin sensitivity and acts as a glucose sink, which is a cornerstone of metabolic health and helps prevent the pro-inflammatory state that can disrupt hormonal balance.

High Intensity Interval Training for Metabolic Recalibration

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) involves short bursts of all-out effort followed by brief recovery periods. This type of training is exceptionally effective at improving metabolic health. HIIT has been shown to significantly enhance insulin sensitivity, meaning the body’s cells can more effectively take up glucose from the blood.

This reduces the overall burden on the pancreas to produce insulin and helps prevent the development of insulin resistance, a condition that is closely linked to hormonal imbalances, including Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) in women and low testosterone in men. The intense nature of HIIT also stimulates a significant release of growth hormone post-exercise, contributing to fat metabolism and cellular repair.

The Clinical Reality Hormonal Optimization Protocols

Lifestyle interventions create the essential foundation for hormonal health. For many individuals, these strategies can produce significant improvements in symptoms and quality of life. There are situations, however, where endogenous production has declined to a point where lifestyle changes alone cannot restore optimal function. In these cases, targeted hormone replacement therapies, or biochemical recalibration protocols, become a logical next step, building upon the foundation established by lifestyle.

These protocols are designed to restore circulating hormone levels to a range associated with youthful vitality and optimal function. This is a clinical intervention that requires careful medical supervision, including baseline blood work and regular monitoring to ensure safety and efficacy.

How Does Hormone Therapy Differ for Men and Women?

The application of hormonal therapy is tailored to the distinct physiological needs of men and women, addressing the specific deficiencies they experience.

For men experiencing andropause with clinically low testosterone, Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) is a standard protocol. A common approach involves weekly intramuscular injections of Testosterone Cypionate to restore testosterone levels. This is often combined with other medications like Gonadorelin to maintain the body’s own testicular function and Anastrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, to control the conversion of testosterone to estrogen.

For women in perimenopause or menopause, the approach is different. Hormone therapy often involves a combination of estrogen and progesterone (for women who have a uterus) to alleviate symptoms like hot flashes, night sweats, and vaginal dryness. In addition, low-dose testosterone therapy is increasingly being recognized as a valuable tool for women to address symptoms of low libido, fatigue, and cognitive fog. These protocols are carefully dosed based on individual symptoms and lab values.

| Protocol Type | Target Audience | Primary Agents | Supporting Agents | Therapeutic Goal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male TRT | Men with symptomatic hypogonadism. | Testosterone Cypionate (weekly injection). | Gonadorelin (to maintain natural production), Anastrozole (to control estrogen). | Restore testosterone to optimal range, improve energy, libido, muscle mass, and mood. |

| Female HRT (Post-Menopause) | Women with significant menopausal symptoms. | Estradiol (patch, gel, or cream), Progesterone (oral or cream). | Low-dose Testosterone Cypionate (subcutaneous injection). | Alleviate vasomotor symptoms, protect bone density, improve sleep, mood, and sexual function. |

| Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy | Adults seeking improved recovery, body composition, and sleep. | Sermorelin, Ipamorelin / CJC-1295. | None typically required. | Stimulate the pituitary’s natural release of Growth Hormone. |

It is important to view these clinical interventions and lifestyle modifications as synergistic. A healthy lifestyle enhances the body’s response to hormone therapy, improves safety, and addresses underlying factors that contribute to hormonal decline. A nutrient-dense diet, regular exercise, and stress management can improve hormone receptor sensitivity, reduce inflammation, and support the metabolic pathways involved in hormone clearance. This integrated approach offers the most comprehensive path to resolving symptoms and reclaiming a state of optimal function and well-being.

Academic

An academic examination of whether lifestyle can resolve symptoms of hormonal decline requires moving beyond symptom management to the cellular and systemic mechanisms at play. The central thesis is that the efficacy of lifestyle interventions is predicated on their ability to modulate the body’s inflammatory state and enhance hormone receptor sensitivity.

Hormonal decline does not occur in a vacuum; it is deeply intertwined with the parallel processes of immunosenescence (the aging of the immune system) and the development of chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation, a state often termed “inflammaging.” This section will analyze the intricate crosstalk between the endocrine, immune, and metabolic systems, positing that the primary leverage point for lifestyle is the mitigation of inflammation, which in turn restores a more favorable environment for hormonal signaling.

The Neuroendocrine-Immune Axis and Inflammaging

The nervous, endocrine, and immune systems form a complex, integrated super-system that constantly communicates to maintain homeostasis. Hormones like cortisol, estrogen, and testosterone are powerful immunomodulators. For instance, estrogen generally has a pro-inflammatory effect at low concentrations and an anti-inflammatory effect at higher, physiological concentrations, while testosterone is broadly considered to be immunosuppressive. The decline of these sex hormones with age disrupts this delicate regulatory balance, contributing to a pro-inflammatory phenotype.

This is compounded by inflammaging, the chronic, sterile, low-grade inflammation that develops with age. This state is driven by an accumulation of senescent cells, which secrete a cocktail of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and proteases known as the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP).

These circulating inflammatory molecules, such as Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), have profound and deleterious effects on the endocrine system. They can suppress the function of the HPG axis at the level of the hypothalamus and pituitary, directly inhibit steroidogenesis in the gonads, and, most critically, induce hormone resistance at the receptor level.

Chronic low-grade inflammation acts as a systemic signal disruptor, impairing the ability of hormones to effectively communicate with their target cells.

How Does Inflammation Induce Hormone Resistance?

Hormone resistance is a state where target tissues become less responsive to hormonal signals, even when circulating hormone levels are adequate. Inflammatory cytokines can induce this resistance through several mechanisms:

- Receptor Downregulation ∞ Chronic exposure to inflammatory signals can cause cells to reduce the number of hormone receptors on their surface, effectively making them “deaf” to the hormonal message.

- Post-Receptor Signaling Disruption ∞ Inflammatory cytokines can activate intracellular signaling pathways, such as the NF-κB and JNK pathways, which interfere with the downstream signaling cascade that is normally initiated by hormone-receptor binding. This means that even if a hormone binds to its receptor, the intended cellular action is blunted or blocked.

- Enzymatic Interference ∞ Inflammation can alter the activity of key enzymes involved in hormone metabolism. For example, inflammation can increase the activity of the aromatase enzyme, which converts testosterone to estrogen, potentially disrupting the optimal androgen-to-estrogen ratio in both men and women.

This framework of inflammation-induced hormone resistance explains why simply replacing hormones with HRT might not be fully effective in some individuals, particularly if the underlying inflammatory state is not addressed. It also provides a powerful rationale for the efficacy of lifestyle interventions, as they are potent modulators of the inflammatory landscape.

Lifestyle Interventions as Applied Immunomodulation

When viewed through this lens, diet and exercise are not merely strategies to manage weight or improve mood; they are precise tools for controlling systemic inflammation and enhancing hormonal signaling.

Nutritional Control of Inflammatory Pathways

The composition of one’s diet has a direct impact on the inflammatory tone of the body. A diet high in processed foods, refined sugars, and unhealthy fats promotes inflammation by increasing oxidative stress, contributing to gut dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability (leaky gut), and providing substrates for pro-inflammatory eicosanoid production. Conversely, a diet rich in whole foods, phytonutrients, and specific fatty acids can profoundly reduce inflammation.

For example, omega-3 fatty acids (found in fatty fish) are precursors to anti-inflammatory resolvins and protectins. Polyphenols (found in berries, green tea, and dark chocolate) can directly inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway. A high-fiber diet nourishes a healthy gut microbiome, which in turn produces short-chain fatty acids like butyrate that have potent systemic anti-inflammatory effects and enhance the integrity of the gut barrier.

Exercise as a Cytokine Modulator

Regular physical activity is a powerful anti-inflammatory intervention. While an acute bout of intense exercise is transiently pro-inflammatory, the long-term adaptation to consistent training is a significant reduction in baseline systemic inflammation. Exercise achieves this through several mechanisms:

- Myokine Release ∞ Contracting muscles release signaling molecules called myokines. One of the most important of these is IL-6. While chronically elevated IL-6 from senescent cells is detrimental, the pulsatile release of IL-6 from muscle during exercise has an anti-inflammatory effect, stimulating the production of other anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 and inhibiting TNF-α.

- Visceral Fat Reduction ∞ Exercise is highly effective at reducing visceral adipose tissue, the metabolically active fat stored around the organs. This tissue is a major source of pro-inflammatory adipokines. Reducing it lowers the overall inflammatory burden on the body.

- Improved Mitochondrial Function ∞ Exercise promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and improves the efficiency of existing mitochondria. Healthy mitochondria produce fewer reactive oxygen species, reducing a primary source of cellular oxidative stress and inflammation.

By reducing systemic inflammation, these lifestyle strategies can improve hormone receptor sensitivity, allowing the body to make better use of its endogenous hormones. This can lead to a significant reduction in symptoms, even if circulating hormone levels do not dramatically increase.

This model suggests that the success of lifestyle interventions is a direct function of their ability to “quiet” the inflammatory noise, thereby allowing the hormonal signal to be heard more clearly. This provides a compelling biological basis for positioning lifestyle as the foundational therapy in addressing the symptoms of age-related hormonal decline. It is the essential first step in restoring the integrity of the body’s entire signaling network.

References

- Vingren, J. L. et al. “Testosterone physiology in resistance exercise and training.” Sports Medicine, vol. 40, no. 12, 2010, pp. 1037-53.

- Kraemer, William J. and Nicholas A. Ratamess. “Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training.” Sports Medicine, vol. 35, no. 4, 2005, pp. 339-61.

- Sood, R. et al. “Prescribing menopausal hormone therapy ∞ an evidence-based approach.” International Journal of Women’s Health, vol. 6, 2014, pp. 47-57.

- Stuenkel, C. A. et al. “Treatment of Symptoms of the Menopause ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 100, no. 11, 2015, pp. 3975-4011.

- Ali, A. & Shah, I. (2020). “Various Factors May Modulate the Effect of Exercise on Testosterone Levels in Men.” BioMed Research International, 2020, 8540458.

- Ho, K. Y. et al. “Effects of sex and age on the 24-hour profile of growth hormone secretion in man ∞ importance of endogenous estradiol levels.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 64, no. 1, 1987, pp. 51-8.

- Santoro, N. et al. “The Menopause Transition ∞ Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW).” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 86, no. 10, 2001, pp. 4680-6.

- Davis, S. R. et al. “Testosterone for low libido in postmenopausal women ∞ a randomized controlled trial.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 359, no. 19, 2008, pp. 2005-17.

- Maki, P. M. “The ‘critical window’ hypothesis of hormone therapy and cognition ∞ a scientific update on clinical evidence.” Menopause, vol. 20, no. 6, 2013, pp. 695-709.

- Franceschi, C. & Campisi, J. “Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases.” The Journals of Gerontology ∞ Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, vol. 69, suppl_1, 2014, pp. S4-9.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here offers a map of the complex territory of your own physiology. It details the known pathways, the established mechanisms, and the potential routes for intervention. This knowledge is a powerful tool, shifting the perspective from one of passive endurance to one of active, informed participation in your own health.

The journey through hormonal change is unique to each individual. Your genetic blueprint, your life history, and your daily choices create a biological signature that is yours alone. Therefore, the most effective path forward is one that is personalized to your specific needs and goals.

Consider the symptoms you experience not as isolated problems, but as signals from a complex, interconnected system. What is your body communicating about its internal environment? Viewing your health through this systemic lens allows you to see the connections between how you eat, how you move, how you sleep, and how you feel.

The strategies discussed are points on a compass, designed to help you orient yourself. The true work lies in applying this knowledge, observing the results within your own body, and making adjustments along the way. This process of self-study, of becoming a careful observer of your own biology, is the ultimate act of empowerment. It is the first and most meaningful step toward navigating your health journey with confidence and intention.

Glossary

hormonal decline

metabolic health

muscle mass

adrenopause

growth hormone

somatopause

testosterone levels

andropause

receptor sensitivity

endocrine system

hormone production

insulin sensitivity

thyroid hormone

resistance training

lifestyle interventions

circulating hormone levels

testosterone replacement therapy

hormone therapy

menopause

improve hormone receptor sensitivity

hormone receptor sensitivity

systemic inflammation

inflammaging

hormone resistance

hpg axis