Fundamentals

You feel a profound sense of fatigue, a persistent chill that has little to do with the ambient temperature, and a mental fog that obscures your thoughts. These sensations are not isolated events; they are the lived experience of a biological system operating just outside its optimal range.

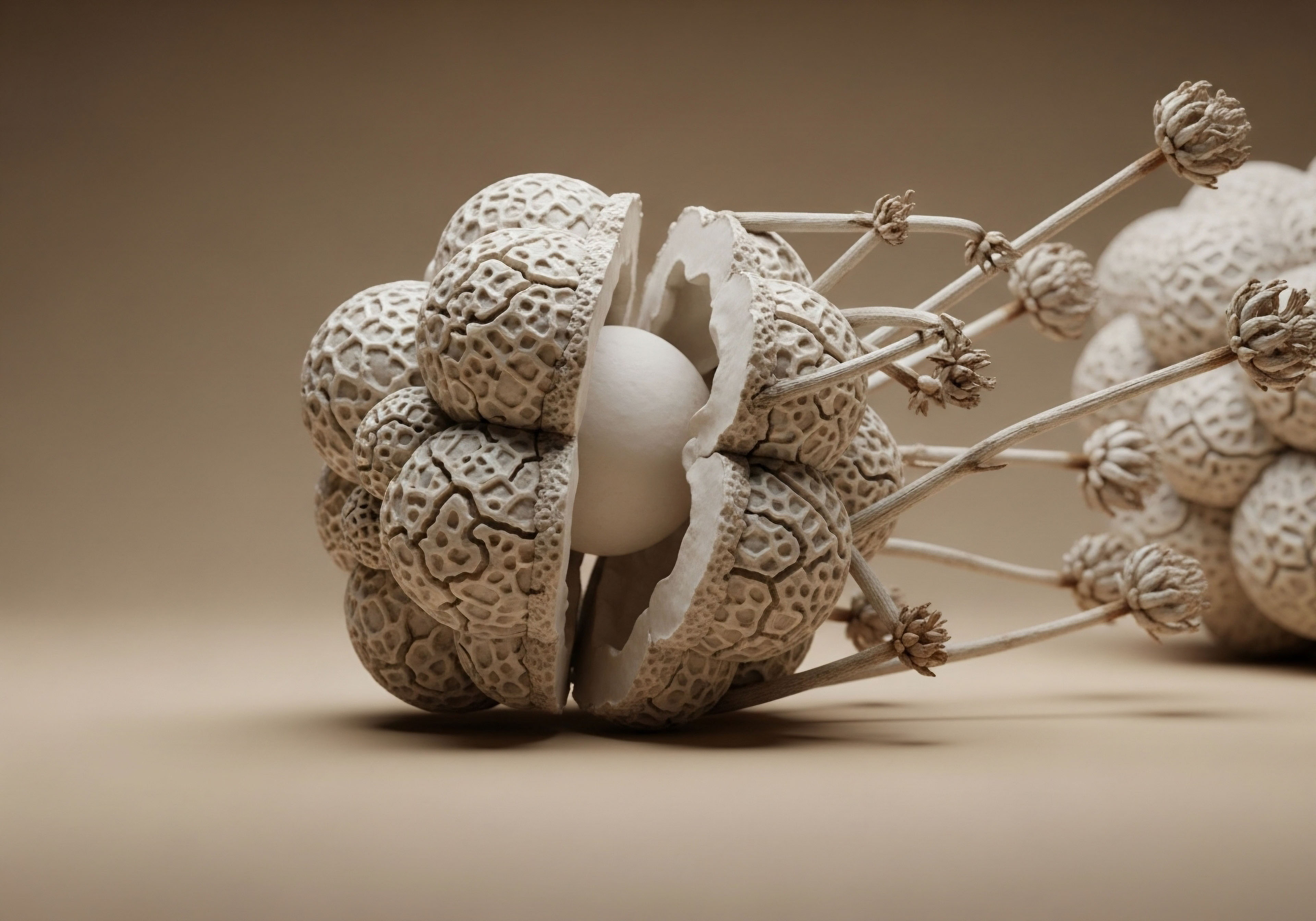

Your body is communicating a subtle yet persistent message of imbalance. The question of whether lifestyle adjustments can restore this equilibrium, or if medication is an inevitable conclusion, begins here, with an understanding of the intricate machinery governing your metabolic rate and energy production. The answer resides within the delicate interplay of signals that orchestrate your physiology, a system centered around a small, butterfly-shaped gland at the base of your neck known as the thyroid.

This gland functions as the master regulator of your metabolic engine. It dictates the speed at which every cell in your body consumes energy, a process as vital to your existence as breathing. When this gland produces an insufficient amount of its crucial hormones, the entire system slows down.

This state, known as hypothyroidism, manifests as a constellation of symptoms that can permeate every aspect of your well-being, from cognitive function and mood to digestive health and physical stamina. Suboptimal thyroid function represents a gray area, a state where lab values may not yet meet the strict criteria for a formal diagnosis, yet the symptoms are undeniably present and disruptive.

This is the space where the conversation about intervention truly begins, grounded in the biology of how your body produces, converts, and utilizes thyroid hormones.

The Command and Control System of Metabolism

Your body’s endocrine network operates through a series of sophisticated feedback loops, akin to a highly responsive internal communication system. The regulation of thyroid function is governed by one such system, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis. This axis represents a continuous conversation between three distinct anatomical structures, each releasing signals that influence the next in a precise cascade. The process originates in the brain, a testament to the profound connection between your neurological and endocrine systems.

The hypothalamus, a region of the brain that acts as a central command center, constantly monitors the levels of thyroid hormone in your bloodstream. When it detects a need for more, it releases Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH). This hormone travels a short distance to the pituitary gland, the master gland of the endocrine system, with a single, clear instruction.

In response to TRH, the pituitary gland secretes Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) into the general circulation. TSH then travels to the thyroid gland, delivering its primary message to increase the production and release of thyroid hormones. The thyroid gland then produces two main hormones, Thyroxine (T4) and Triiodothyronine (T3).

Once these hormones reach a sufficient level in the blood, they signal back to the hypothalamus and pituitary to decrease their stimulating signals, thus completing the feedback loop and ensuring a state of balance, or homeostasis.

What Are the Primary Thyroid Hormones?

The thyroid gland produces hormones that are essential for life, synthesized from the amino acid tyrosine and the mineral iodine. Understanding the distinction between the two primary hormones is fundamental to comprehending thyroid physiology and the potential points of intervention. The thyroid produces mostly T4, which is a prohormone, a relatively inactive storage form of the hormone.

Its primary role is to be a stable reservoir, circulating throughout the body, ready for activation. The biologically active hormone, the one that directly interacts with cellular receptors to drive metabolism, is T3. The majority of T3 is not produced in the thyroid gland itself; it is converted from T4 in peripheral tissues, most notably the liver, kidneys, and gut.

This conversion process is a critical control point in thyroid function. The body can upregulate or downregulate this conversion based on its metabolic needs and overall health status. Therefore, having adequate T4 production is only the first step. The body must also possess the capability to efficiently convert T4 into the active T3 for the system to function correctly.

Any factor that impairs this conversion can lead to symptoms of hypothyroidism, even if the thyroid gland itself is producing sufficient T4.

The Lived Experience of a Slowed Metabolism

When the production of thyroid hormones falters or the conversion of T4 to T3 is impaired, the metabolic rate of every cell declines. This systemic slowdown creates a cascade of physiological consequences that manifest as the symptoms you may be experiencing. The fatigue is a direct result of decreased energy production at the cellular level.

The feeling of coldness stems from a reduction in thermogenesis, the process by which cells generate heat. Brain fog and memory issues arise because neurons, which are highly metabolically active, lack the hormonal stimulation needed for optimal function. Constipation occurs as the smooth muscles of the digestive tract become sluggish.

Dry skin, hair loss, and brittle nails reflect the slowed rate of cellular regeneration. These symptoms are direct biological readouts of your internal hormonal state. They are tangible evidence that the system responsible for setting your body’s pace is operating at a diminished capacity. Recognizing these signs as physiological signals, rather than personal failings, is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality.

A diminished thyroid output slows the metabolic rate of every cell, creating a systemic state of reduced energy and function.

The journey to understanding your thyroid health involves looking at this system from a holistic perspective. It requires an appreciation for the interconnectedness of your endocrine, nervous, and digestive systems. The question of whether lifestyle changes alone can correct a suboptimal state is a question of inputs and outputs.

The HPT axis and the subsequent hormonal cascade are profoundly influenced by the raw materials you provide your body through nutrition, the stress signals you send through your nervous system, and the quality of rest you allow for repair and regeneration.

Before exploring the necessity of medication, the logical first step is to examine the foundational pillars that support the healthy function of this elegant and vital system. By addressing the inputs, you create the optimal conditions for the system to recalibrate itself. This process is not about a single intervention but about creating a biological environment that fosters resilience and promotes the body’s innate capacity for balance.

Intermediate

The conversation about correcting suboptimal thyroid function moves beyond simple mechanics into the realm of biochemistry and environmental influence. The HPT axis, while elegant in its design, does not operate in a vacuum. It is exquisitely sensitive to the quality of its inputs, from the micronutrients required for hormone synthesis to the disruptive signals generated by chronic stress.

Lifestyle interventions are not merely supportive measures; they are targeted biological signals that can directly influence thyroid hormone production, conversion, and cellular uptake. This section explores the precise mechanisms through which targeted changes in your nutrition, stress modulation, sleep patterns, and environmental exposures can recalibrate thyroid physiology, potentially normalizing function before a pharmaceutical approach becomes necessary.

Subclinical hypothyroidism is a state defined by an elevated TSH level while T4 and T3 levels remain within the standard laboratory reference range. This biochemical picture indicates that the pituitary gland is working harder, shouting at the thyroid to maintain adequate hormone production.

It is a sign of impending thyroid fatigue, a signal that the system is under strain. Lifestyle-centric strategies are aimed at reducing this strain. They work by providing the essential building blocks for hormone creation, removing obstacles to hormone conversion, and mitigating the systemic inflammation and stress that disrupt the delicate endocrine conversation. This approach is rooted in the principle of restoring the body’s self-regulatory capacity by optimizing the physiological environment in which the thyroid operates.

Nutritional Biochemistry and Thyroid Synthesis

Thyroid hormones are synthesized from specific raw materials. A deficiency in any of these essential components can create a bottleneck in the production line, leading to reduced thyroid output. A strategic nutritional protocol provides the necessary substrates for the thyroid to perform its function effectively. This goes far beyond a generic “healthy diet” and involves a targeted approach to ensure key micronutrients are present in optimal amounts.

Can Nutrient Deficiencies Impair Hormone Production?

The creation and activation of thyroid hormones is a multi-step enzymatic process, with each step dependent on specific vitamins and minerals acting as cofactors. A deficiency in any of these key nutrients can directly impair the thyroid cascade. The body’s ability to manufacture and utilize these critical metabolic regulators is contingent upon a consistent supply of these elemental building blocks.

- Iodine ∞ This is the foundational structural component of thyroid hormones. The numbers in T4 and T3 refer to the number of iodine atoms attached to the tyrosine backbone. The thyroid gland actively traps iodine from the bloodstream to be used in hormone synthesis. Insufficient iodine intake directly limits the amount of hormone that can be produced, leading to hypothyroidism and potentially goiter, an enlargement of the thyroid gland as it tries to compensate.

- Tyrosine ∞ This amino acid forms the protein backbone of thyroid hormones. While tyrosine deficiency is rare, ensuring adequate protein intake is a prerequisite for healthy thyroid function. The body can synthesize tyrosine from another amino acid, phenylalanine, but a diet sufficient in complete protein sources covers this requirement.

- Selenium ∞ This trace mineral is a critical cofactor for the family of enzymes known as deiodinases, which are responsible for converting the inactive T4 into the active T3 in peripheral tissues. Selenium deficiency can significantly impair this conversion process, leading to a functional hypothyroidism where T4 levels are normal, but active T3 is low. Selenium also plays a vital role in protecting the thyroid gland from oxidative stress generated during hormone synthesis.

- Zinc ∞ Zinc is another mineral that plays a role in the function of deiodinase enzymes. It is also required for the proper function of the pituitary gland in releasing TSH. Zinc deficiency can lead to reduced TSH production and impaired T4 to T3 conversion, affecting the HPT axis at multiple levels.

- Iron ∞ The enzyme thyroid peroxidase (TPO), which is responsible for attaching iodine to tyrosine to build thyroid hormones, is iron-dependent. Iron deficiency, with or without anemia, can impair the activity of this enzyme, leading to decreased hormone production. This is particularly relevant for menstruating women, who are at a higher risk for iron deficiency.

A therapeutic lifestyle approach involves a diet rich in whole foods that supply these nutrients. Sources of iodine include sea vegetables and seafood. Selenium is abundant in Brazil nuts, fish, and poultry. Zinc is found in oysters, beef, and pumpkin seeds. Iron is present in red meat, lentils, and spinach. By focusing on nutrient density, you provide the thyroid with the complete toolkit it needs for optimal hormone production and activation.

| Nutrient | Primary Role in Thyroid Physiology | Common Dietary Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Iodine | Structural component of T4 and T3 hormones. | Seaweed, cod, yogurt, iodized salt. |

| Selenium | Cofactor for deiodinase enzymes (T4 to T3 conversion); antioxidant protection. | Brazil nuts, tuna, sardines, eggs. |

| Zinc | Supports TSH production and T4 to T3 conversion. | Oysters, beef, pumpkin seeds, lentils. |

| Iron | Required for the function of thyroid peroxidase (TPO) enzyme in hormone synthesis. | Red meat, spinach, lentils, fortified cereals. |

| Tyrosine | Amino acid backbone of thyroid hormones. | Meat, fish, eggs, dairy, nuts, beans. |

The Intersection of Stress and Thyroid Function

The body’s stress response system, governed by the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, has a profound and direct impact on the HPT axis. When you experience chronic stress, whether physical, emotional, or psychological, the HPA axis is persistently activated, leading to elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol. This has several detrimental effects on thyroid physiology.

Firstly, high cortisol levels can suppress the pituitary gland’s release of TSH. This effectively dampens the primary signal to the thyroid gland, reducing overall hormone production. Secondly, cortisol inhibits the activity of the deiodinase enzymes, particularly in the liver. This shunts the conversion of T4 away from the active T3 and towards an inactive form called Reverse T3 (rT3).

Reverse T3 acts as a brake on metabolism, binding to T3 receptors without activating them, effectively blocking the action of the active hormone. This is a protective mechanism during times of acute stress or famine, designed to conserve energy. In the context of chronic modern stress, it creates a state of cellular hypothyroidism.

Finally, chronic inflammation, a common consequence of sustained stress, can decrease the sensitivity of thyroid hormone receptors on cells, meaning that even if T3 is present, it cannot effectively deliver its metabolic message.

Chronic elevation of cortisol directly suppresses thyroid-stimulating signals and impairs the activation of thyroid hormone in the body’s tissues.

Lifestyle interventions aimed at stress modulation, such as mindfulness meditation, deep breathing exercises, yoga, and spending time in nature, are potent tools for downregulating the HPA axis. By lowering cortisol levels, these practices can restore normal pituitary function, improve the T4 to T3 conversion ratio, and enhance cellular sensitivity to thyroid hormones. Managing stress is a direct and powerful method of supporting thyroid health.

Restoration through Sleep and Circadian Rhythm

Sleep is a critical period for hormonal regulation and tissue repair. The release of TSH follows a distinct circadian rhythm, peaking during the night to stimulate thyroid hormone production in preparation for the metabolic demands of the coming day.

Disrupted sleep and a misaligned circadian rhythm, common in modern life due to artificial light exposure and irregular schedules, can flatten this TSH surge. This leads to a lower overall output of thyroid hormones. Sleep deprivation also acts as a significant physiological stressor, activating the HPA axis and increasing cortisol, which further compounds the negative effects on thyroid function.

Prioritizing consistent, high-quality sleep is a non-negotiable aspect of any protocol aimed at optimizing thyroid health. This involves establishing a regular sleep-wake cycle, creating a dark and cool sleep environment, and avoiding stimulants and blue light exposure before bed. Aligning your lifestyle with your body’s natural rhythms provides a powerful signal of safety and stability to the endocrine system, allowing for proper hormonal regulation.

Goitrogens and Endocrine Disruptors

Certain compounds found in food and the environment can interfere with thyroid function. Goitrogens are substances present in some raw cruciferous vegetables (like broccoli, kale, and cabbage) that can inhibit the thyroid’s uptake of iodine, particularly in the context of iodine deficiency.

For most individuals with adequate iodine status, consuming cooked cruciferous vegetables poses no risk and offers significant health benefits. However, for someone with diagnosed suboptimal thyroid function, an awareness of goitrogen intake, especially from raw sources like juices, is a relevant consideration.

Of greater concern are endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) found in plastics (BPA, phthalates), pesticides, and industrial chemicals (PCBs, perchlorates). These compounds can interfere with thyroid function at multiple levels. Some EDCs can block iodine uptake by the thyroid, others can inhibit the TPO enzyme, and some can interfere with thyroid hormone transport and metabolism.

Reducing exposure to these chemicals by filtering drinking water, choosing glass over plastic containers, and opting for organic produce when possible can decrease the body’s toxic load and reduce the chemical interference with the endocrine system. A lifestyle-focused approach recognizes that the thyroid is part of a larger ecosystem, and reducing external disruptors is as important as providing internal support.

| Intervention Area | Specific Action | Primary Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritional Protocol | Ensuring adequate intake of iodine, selenium, zinc, iron. | Provides essential cofactors for hormone synthesis (TPO) and conversion (deiodinases). |

| Stress Modulation | Mindfulness, yoga, meditation, time in nature. | Downregulates the HPA axis, lowers cortisol, and reduces inhibition of TSH and T4-T3 conversion. |

| Sleep Hygiene | Consistent sleep-wake cycle, dark environment, blue light avoidance. | Restores the natural circadian rhythm of TSH release and reduces cortisol from sleep deprivation. |

| Environmental Awareness | Reducing exposure to EDCs in plastics, water, and food. | Minimizes chemical interference with iodine uptake, hormone synthesis, and transport. |

The decision to pursue lifestyle changes as a primary intervention for suboptimal thyroid function is a decision to engage with your own biology on a fundamental level. It is a systematic process of identifying and removing obstacles while simultaneously providing the resources the body needs to self-regulate.

For many, particularly those in the subclinical stage, this approach can be sufficient to restore TSH to an optimal range and resolve symptoms. It addresses the root causes of the imbalance, promoting not just a normalized lab value, but a state of systemic wellness. This path requires commitment and consistency, yet it empowers you with the tools to become an active participant in your own health restoration.

Academic

The progression from suboptimal thyroid function to overt hypothyroidism is frequently driven by an autoimmune process, specifically Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. This condition, the leading cause of hypothyroidism in iodine-sufficient regions, reframes the therapeutic question. The central issue is not a primary failure of the thyroid gland itself, but a case of mistaken identity, where the body’s own immune system targets and progressively destroys thyroid tissue.

Therefore, an academic exploration of correcting thyroid dysfunction must investigate the origins of this autoimmune dysregulation. The evidence increasingly points to a complex interplay between genetic predisposition, environmental triggers, and the integrity of the gastrointestinal system. The gut-thyroid axis is a critical concept in this discussion, positing that the health of the intestinal barrier and the composition of the gut microbiome are primary modulators of systemic autoimmunity, including the attack on the thyroid gland.

A therapeutic strategy grounded in this understanding moves beyond simply supporting thyroid hormone production and focuses on re-establishing immune tolerance. This involves a deep dive into the molecular mechanisms that link intestinal permeability, microbial dysbiosis, and the loss of self-tolerance that characterizes Hashimoto’s.

Lifestyle interventions, from this perspective, are not merely “supportive”; they are targeted immunomodulatory and barrier-restoring strategies. They aim to remove the antigenic triggers and quell the systemic inflammation that perpetuate the autoimmune assault, creating the possibility for the thyroid to heal and function without the constant threat of destruction. This approach seeks to address the cause of the fire, not just manage the smoke.

Intestinal Permeability as an Autoimmune Precursor

The intestinal epithelium is a vast surface area designed for nutrient absorption, yet it must also function as a highly selective barrier, preventing the passage of harmful substances from the gut lumen into the bloodstream. This barrier is maintained by complex protein structures called tight junctions, which seal the space between adjacent epithelial cells.

In a state of increased intestinal permeability, colloquially known as “leaky gut,” these tight junctions become compromised, allowing larger molecules, such as undigested food proteins, bacterial fragments (lipopolysaccharides or LPS), and other antigens, to pass into the circulation. This breach of the barrier is a critical event in the initiation of autoimmunity.

The protein zonulin is a key regulator of tight junction integrity. Its release is triggered by certain stimuli, including exposure to gliadin (a component of gluten) and specific gut bacteria. Elevated levels of zonulin lead to the disassembly of tight junctions and increased intestinal permeability.

Studies have demonstrated that patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis often have significantly higher levels of serum zonulin compared to healthy controls, indicating a compromised gut barrier. Once these foreign antigens enter the bloodstream, they encounter the systemic immune system, which rightfully identifies them as invaders and mounts an inflammatory response. This chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation creates an environment conducive to the development of autoimmune conditions.

What Is the Mechanism of Molecular Mimicry?

The concept of molecular mimicry provides a compelling explanation for how a response to a foreign antigen can evolve into an attack on the body’s own tissues. This phenomenon occurs when a peptide sequence in a foreign protein (from a food, virus, or bacterium) bears a strong structural resemblance to a peptide sequence in a human protein.

The immune system, in its effort to eliminate the foreign invader, produces antibodies and activates T-cells that recognize this specific sequence. However, due to the structural similarity, these same immune cells and antibodies can then mistakenly recognize and attack the body’s own proteins.

In the context of Hashimoto’s, several instances of molecular mimicry have been proposed. For example, the protein gliadin has structural similarities to thyroid peroxidase (TPO), the enzyme critical for thyroid hormone synthesis. An immune response initiated against gliadin in a genetically susceptible individual could lead to the production of cross-reactive antibodies that also target TPO.

Similarly, proteins from certain bacteria, such as Yersinia enterocolitica, have been shown to mimic components of the TSH receptor. An infection with this bacterium could trigger an autoimmune response that subsequently targets the thyroid gland. Increased intestinal permeability is the gateway that allows these foreign antigens to be presented to the systemic immune system in the first place, setting the stage for this case of mistaken identity.

The Microbiome’s Role in Immune Homeostasis

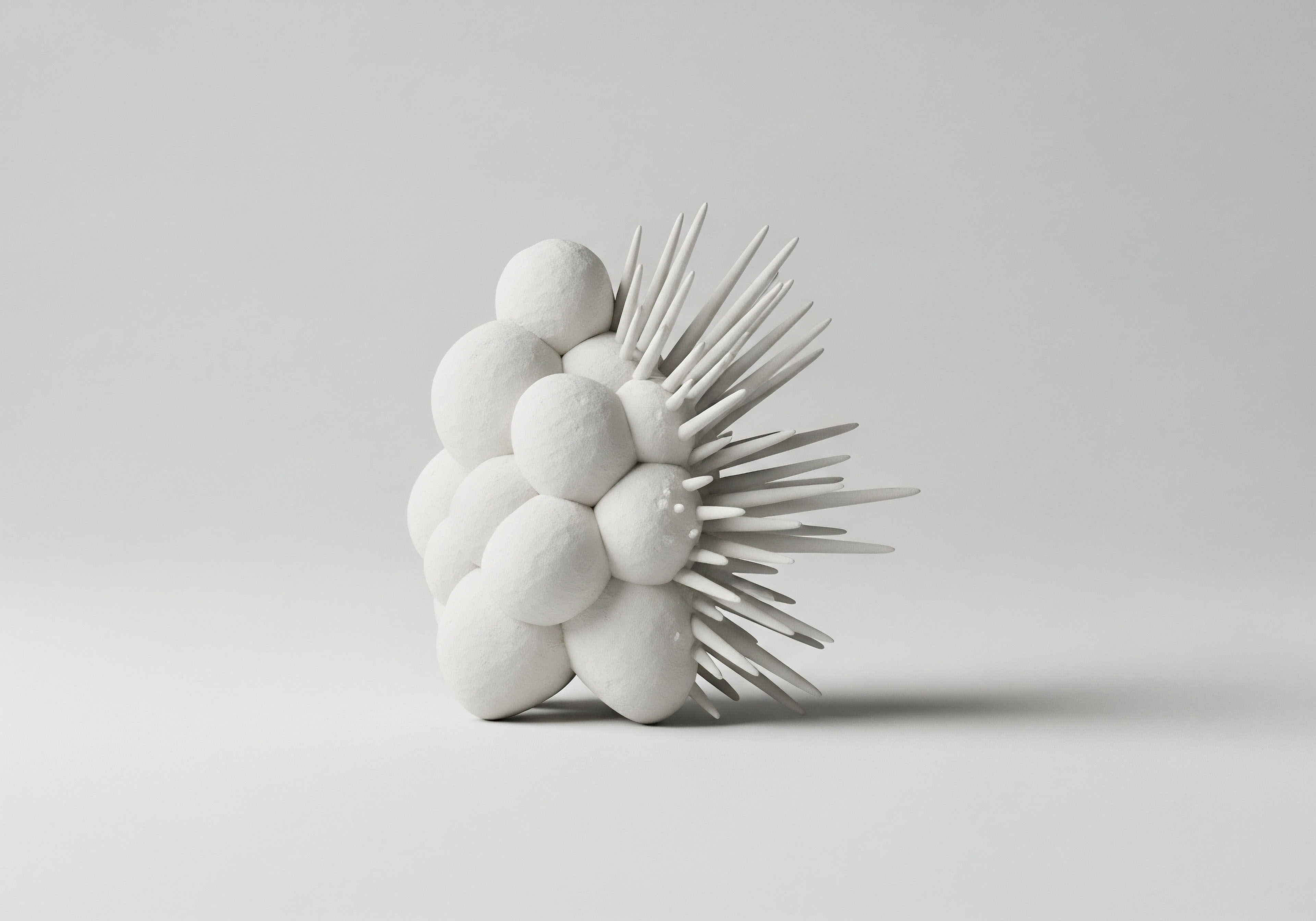

The trillions of microorganisms residing in the human gut, collectively known as the gut microbiome, play a fundamental role in educating and regulating the host immune system. A balanced, diverse microbiome promotes immune tolerance by fostering the development of regulatory T-cells (Tregs).

Tregs are a specialized subset of immune cells whose function is to suppress excessive immune responses and prevent autoimmunity. They act as the peacekeepers of the immune system, ensuring that it does not overreact to harmless substances or attack the body’s own cells.

Gut bacteria produce a variety of metabolites that directly influence immune function, with short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, propionate, and acetate being among the most important. Butyrate, produced by the fermentation of dietary fiber by specific bacteria, serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes (the cells lining the colon), thereby strengthening the gut barrier.

It also has potent immunomodulatory effects, promoting the differentiation of Tregs and inhibiting inflammatory pathways. Research has shown that patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis often exhibit gut dysbiosis, characterized by a reduction in beneficial, butyrate-producing bacteria (like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus) and an overgrowth of pro-inflammatory species.

This microbial imbalance can lead to a reduction in SCFA production, a weakened gut barrier, and a shift in the immune system away from tolerance (Treg-dominant) and towards inflammation (Th1/Th17-dominant), the very immune signature observed in Hashimoto’s.

Dysbiosis in the gut microbiome can disrupt immune tolerance, fostering the specific inflammatory conditions that drive the autoimmune attack on the thyroid gland.

Furthermore, the gut microbiome influences the availability and metabolism of key nutrients essential for thyroid health. Gut bacteria can synthesize certain B vitamins, regulate the absorption of minerals like selenium and zinc, and even contribute to the conversion of T4 to T3 through their own deiodinase-like enzymatic activity. Therefore, a dysbiotic state can contribute to thyroid dysfunction through both immunological and metabolic pathways.

How Can Lifestyle Interventions Target the Gut Thyroid Axis?

A therapeutic lifestyle protocol designed to address the autoimmune underpinnings of thyroid dysfunction focuses on restoring intestinal barrier integrity and rebalancing the gut microbiome. This is a highly targeted approach that goes beyond generic wellness advice.

- Antigenic Load Reduction ∞ This involves the temporary elimination of common dietary triggers of intestinal permeability and immune reactivity. Gluten is often a primary focus due to gliadin’s known effect on zonulin. Other potential triggers, such as dairy (casein) and processed foods containing emulsifiers and other additives that can damage the gut lining, may also be removed. This strategy, often implemented as an elimination diet, aims to reduce the constant influx of antigens that are challenging the immune system.

- Microbiome Repopulation and Nourishment ∞ The focus shifts to actively cultivating a diverse and beneficial gut ecosystem. This is achieved by introducing a wide variety of plant-based fibers (prebiotics) that feed beneficial bacteria. Foods rich in polyphenols, such as berries, green tea, and dark chocolate, also support a healthy microbiome. Fermented foods containing live probiotic cultures (like sauerkraut, kimchi, and kefir) can help reintroduce beneficial species. In some cases, targeted probiotic supplementation with specific strains like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium may be used.

- Barrier Repair and Inflammation Quelling ∞ Specific nutrients and compounds can support the healing of the intestinal lining. The amino acid L-glutamine is a key fuel source for enterocytes. Nutrients like zinc and vitamin D are also critical for maintaining tight junction function. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish, have potent anti-inflammatory properties that can help quell the systemic inflammation driving the autoimmune process.

This immunomodulatory, gut-centric approach represents a sophisticated application of lifestyle medicine. It posits that for a significant subset of individuals with suboptimal thyroid function, particularly those with positive thyroid antibodies, medication may not address the underlying autoimmune process.

By focusing on the root drivers of the immune attack ∞ a permeable gut barrier and a dysbiotic microbiome ∞ these interventions offer a path to potentially halt the progression of the disease. This strategy requires a deep understanding of the patient’s individual triggers and a personalized, systematic approach. It is a powerful demonstration of how targeted lifestyle changes can function as a primary therapeutic modality, aiming to restore not just hormonal balance, but fundamental immune tolerance.

References

- Knezevic, J. Starchl, C. Tmava Berisha, A. & Amrein, K. “Thyroid-Gut-Axis ∞ How Does the Microbiota Influence Thyroid Function?” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 6, 2020, p. 1769.

- Virili, C. Fallahi, P. Antonelli, A. Benvenga, S. & Centanni, M. “Gut microbiota and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.” Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, vol. 19, no. 4, 2018, pp. 293-300.

- Liontiris, M. I. & Mazokopakis, E. E. “A concise review of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT) and the importance of iodine, selenium, vitamin D and gluten on the autoimmunity and dietary management of HT patients.” Hellenic Journal of Nuclear Medicine, vol. 20, no. 1, 2017, pp. 51-56.

- Farhangi, M. A. Dehghan, P. Tajmiri, S. & Abbasi, M. M. “The effects of selenium and vitamin E supplementation on fatigue and physical performance in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.” Immunology and Medical Microbiology, vol. 2, no. 1, 2017, pp. 1-8.

- Lerner, A. Jeremias, P. & Matthias, T. “The world incidence and prevalence of autoimmune diseases is increasing.” International Journal of Celiac Disease, vol. 3, no. 4, 2015, pp. 151-155.

- Fasano, A. “Zonulin and its regulation of intestinal barrier function ∞ the biological door to inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer.” Physiological Reviews, vol. 91, no. 1, 2011, pp. 151-175.

- Gärtner, R. Gasnier, B. C. Dietrich, J. W. Krebs, B. & Angstwurm, M. W. “Selenium supplementation in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis decreases thyroid peroxidase antibodies concentrations.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 87, no. 4, 2002, pp. 1687-1691.

- Ventura, M. Melo, M. & Carrilho, F. “Selenium and Thyroid Disease ∞ From Pathophysiology to Treatment.” International Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 2017, 2017, Article ID 1297658.

- Toulis, K. A. Anastasilakis, A. D. Tzellos, T. G. Goulis, D. G. & Kouvelas, D. “Selenium supplementation in the treatment of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis ∞ a systematic review and a meta-analysis.” Thyroid, vol. 20, no. 10, 2010, pp. 1163-1173.

- Zhao, F. Feng, J. Li, J. & Zhao, L. “Alterations of the Gut Microbiota in Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis Patients.” Thyroid, vol. 28, no. 2, 2018, pp. 175-186.

Reflection

The knowledge you have gained provides a new lens through which to view your body’s signals. The sensations of fatigue or mental fog are no longer abstract frustrations; they are data points, reflecting a complex and responsive biological system.

You now understand the conversation happening between your brain and your thyroid, the critical role of micronutrients in every hormonal message, and the profound influence of your internal and external environments on this delicate balance. This understanding is the foundational step. It transforms the feeling of being a passive victim of your symptoms into the reality of being an active, informed participant in your own physiology.

The path forward is one of personalization and deep listening. Your unique genetic makeup, your personal history, and your current lifestyle create a biological context that is entirely your own. The principles discussed here are the map, but you are the cartographer of your own journey back to vitality.

Consider this information not as a set of rigid rules, but as a toolkit for self-experimentation and observation. How does your body respond to a greater emphasis on restorative sleep? What shifts do you notice when you manage your stress with intention?

This process of inquiry, of connecting external actions to internal sensations, is where true healing begins. The ultimate goal is to cultivate a state of resilience, building a physiological foundation so robust that your body can maintain its equilibrium amidst the inevitable challenges of life.