Fundamentals

You have the blood test results in your hand. The columns of numbers and clinical ranges seem to stare back, offering a verdict that feels both foreign and intensely personal. Perhaps you recognize the feeling that prompted the test in the first place—a persistent fatigue that sleep doesn’t fix, a subtle shift in your mood or metabolism, or a general sense that your body is operating with a set of instructions you no longer understand. The question that follows is immediate and deeply practical ∞ Can you, through your own actions, correct the imbalances reflected on this page?

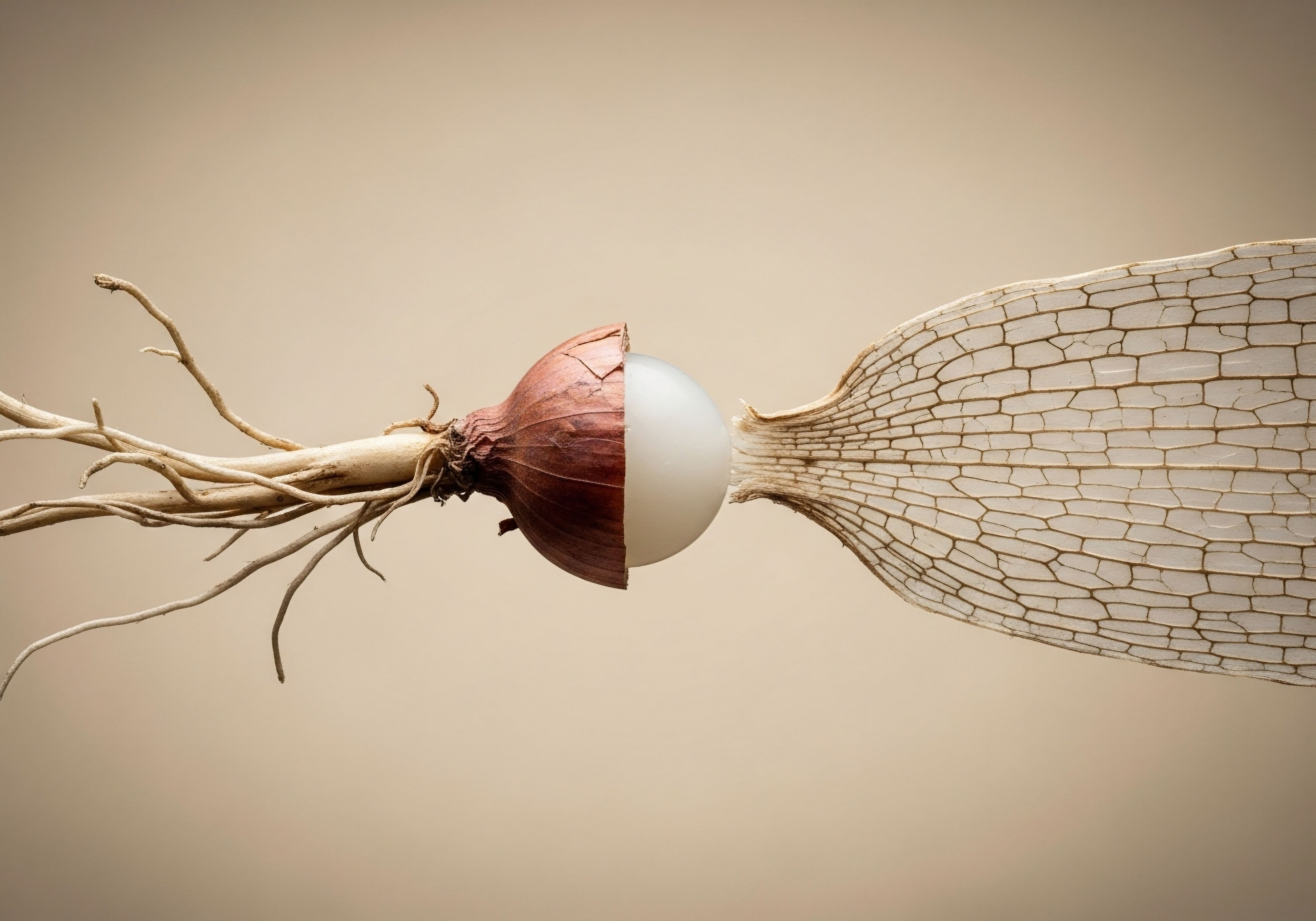

The answer begins with a foundational understanding of your body as a dynamic, responsive system. Your hormonal state is a direct reflection of the signals it receives. Therefore, dedicated lifestyle changes Meaning ∞ Lifestyle changes refer to deliberate modifications in an individual’s daily habits and routines, encompassing diet, physical activity, sleep patterns, stress management techniques, and substance use. can absolutely serve as the primary intervention to recalibrate the biological conversations that govern your health.

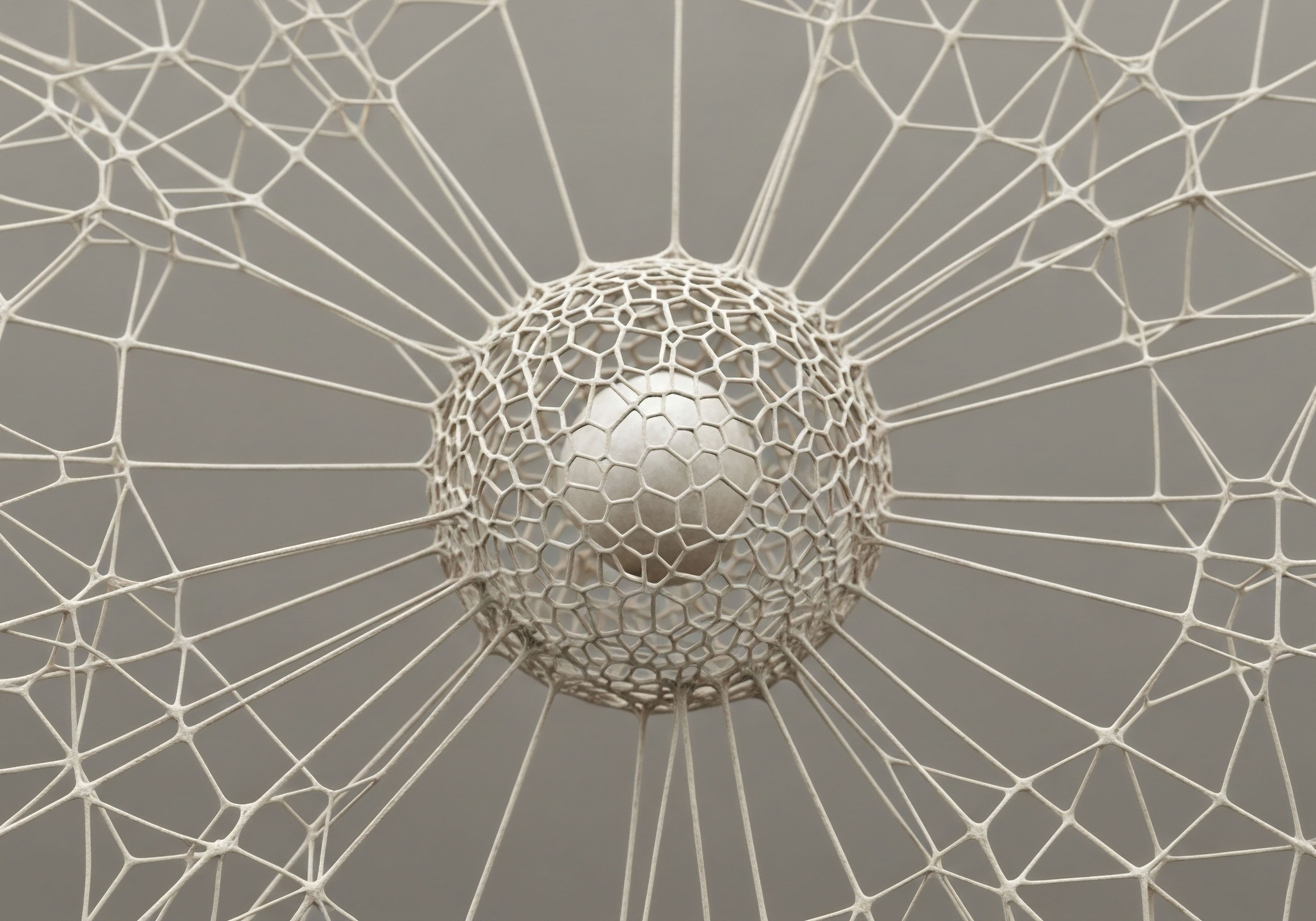

Your body’s endocrine system Meaning ∞ The endocrine system is a network of specialized glands that produce and secrete hormones directly into the bloodstream. is a sophisticated communication network, a series of glands that produce and release hormones. These chemical messengers travel through your bloodstream, carrying precise instructions to virtually every cell, organ, and system. They dictate your energy levels, your response to stress, your metabolic rate, your reproductive function, and even your cognitive clarity. When we speak of a hormonal imbalance, we are describing a disruption in this communication.

The messages are being sent at the wrong time, in the wrong volume, or are being misinterpreted at their destination. Lifestyle interventions Meaning ∞ Lifestyle interventions involve structured modifications in daily habits to optimize physiological function and mitigate disease risk. are powerful because they directly influence the quality, timing,and clarity of these foundational signals.

Your hormonal status is a direct and dynamic response to the inputs of your daily life, not a fixed state.

To begin correcting imbalances, we must first focus on the most influential inputs that your body receives every single day. These are the pillars upon which your endocrine health is built. By consciously managing them, you begin to rewrite the instructions you send to your own biology. The process is one of systematic recalibration, starting with the core elements of human physiology.

Nutrition as Biological Information

The food you consume does far more than provide caloric energy. Every meal delivers a complex set of molecules that act as information, instructing your hormones on how to behave. Proteins, fats, and carbohydrates are the primary messengers. A diet high in refined sugars and processed carbohydrates, for instance, signals for a surge of insulin, a potent metabolic hormone.

When this signal is sent too frequently and too intensely, it can lead to insulin resistance, a state where your cells become “numb” to insulin’s message. This single issue can cascade into other imbalances, affecting sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen. Conversely, a diet rich in fiber, high-quality protein, and healthy fats sends a message of stability, promoting balanced insulin release and providing the raw materials needed to synthesize other essential hormones. Micronutrients like selenium and iodine are critical for thyroid hormone production, while healthy fats are the literal building blocks for steroid hormones like testosterone and cortisol. Your dietary choices are a daily opportunity to provide your endocrine system with clear, effective instructions.

Movement as a Potent Stimulus

Physical activity is a powerful modulator of your endocrine system. Different types of exercise send distinct signals that elicit specific hormonal responses. Resistance training, for example, is a potent stimulus for the production of anabolic, or building, hormones. Lifting heavy weights creates microscopic tears in muscle fibers, signaling the body to release testosterone and growth hormone Meaning ∞ Growth hormone, or somatotropin, is a peptide hormone synthesized by the anterior pituitary gland, essential for stimulating cellular reproduction, regeneration, and somatic growth. to repair and strengthen the tissue.

This process supports healthy muscle mass and metabolic function. Aerobic exercise, on the other hand, is particularly effective at improving insulin sensitivity, making your cells more responsive to insulin’s signal to uptake glucose from the blood. Regular physical activity also helps regulate the body’s primary stress hormone, cortisol. While intense exercise can cause a temporary spike in cortisol, consistent training helps to moderate its overall levels, improving your resilience to stress over time. Movement is a direct conversation with your muscular and endocrine systems, a way to request strength, efficiency, and balance.

Sleep and Circadian Rhythm as the Master Clock

Your body operates on a 24-hour internal clock known as the circadian rhythm. This biological pacemaker, located in the brain, orchestrates the daily ebb and flow of nearly every hormone. The most prominent example is the cortisol rhythm. In a healthy individual, cortisol levels are highest in the morning to promote wakefulness and energy, and gradually decline throughout the day, reaching their lowest point at night to allow for restful sleep.

This rhythm is primarily set by your exposure to light and darkness. When this cycle is disrupted by poor sleep, late-night screen time, or irregular schedules, the cortisol rhythm flattens. This dysregulation can lead to feelings of being “wired and tired,” daytime fatigue, and nighttime wakefulness. Sleep itself is a critical period for hormonal maintenance.

During deep sleep, the body releases growth hormone, which is essential for cellular repair. Inadequate sleep has been shown to impair insulin sensitivity Meaning ∞ Insulin sensitivity refers to the degree to which cells in the body, particularly muscle, fat, and liver cells, respond effectively to insulin’s signal to take up glucose from the bloodstream. and disrupt the hormones that regulate appetite, ghrelin and leptin. Prioritizing consistent, high-quality sleep is perhaps the single most effective way to stabilize your body’s master hormonal clock.

Intermediate

Understanding that lifestyle choices are potent hormonal signals is the first step. The next is to appreciate the intricate systems that translate these signals into the biochemical reality reflected in your blood tests. Your endocrine function is governed by complex feedback loops, primarily orchestrated by the brain. Two of these systems, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, are central to your well-being.

They function like a corporate hierarchy, with the hypothalamus acting as the CEO, the pituitary as the senior manager, and the adrenal and gonadal glands as the operational departments. Lifestyle inputs directly influence the directives sent down from the top, affecting the entire chain of command.

The HPA Axis the Central Stress Response System

The HPA axis Meaning ∞ The HPA Axis, or Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis, is a fundamental neuroendocrine system orchestrating the body’s adaptive responses to stressors. is your body’s command center for managing stress. When the hypothalamus perceives a stressor—be it psychological pressure, a physical threat, or an internal issue like inflammation or low blood sugar—it releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). CRH signals the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn travels to the adrenal glands and instructs them to produce cortisol. Cortisol then mobilizes energy, increases alertness, and dampens non-essential functions to handle the perceived threat.

In a healthy system, rising cortisol levels send a negative feedback signal back to the brain, shutting down the stress response. Chronic stress, however, disrupts this delicate feedback loop. Constant activation from sources like poor sleep, inflammatory diets, or relentless work demands can lead to HPA axis dysfunction. This can manifest in two ways ∞ initially as chronically high cortisol, and later, as a blunted or depleted cortisol response, leading to profound fatigue and burnout. Correcting this requires a systematic reduction of the total stress load on your system through targeted lifestyle protocols.

What Is the Connection between Stress and Female Hormones?

The HPA and HPG axes are deeply intertwined. The body prioritizes survival, and in a state of chronic stress, the HPA axis effectively tells the HPG axis to downregulate its functions. Reproduction is metabolically expensive and becomes a low priority when the body perceives it is under constant threat. High levels of cortisol can suppress the release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, which is the primary signal that initiates the entire female reproductive cycle.

This can lead to irregular or absent menstrual cycles, a common symptom in women under significant stress. Furthermore, the precursor hormone pregnenolone is a building block for both cortisol and sex hormones like progesterone. In a state of high stress, the body may divert pregnenolone toward cortisol production in a phenomenon sometimes called “pregnenolone steal,” potentially leaving insufficient substrate for progesterone production. This can contribute to symptoms of estrogen dominance and PMS. Stress reduction practices, therefore, are a direct intervention for supporting female hormonal health.

Hormonal balance is achieved when the body’s primary signaling systems, like the HPA and HPG axes, operate without chronic interference.

Lifestyle Protocols for System Recalibration

Correcting imbalances in these systems requires moving beyond general advice to specific, evidence-based protocols. These interventions are designed to provide the clear, consistent signals your body needs to restore healthy function.

- Nutritional Protocol for Insulin Sensitivity A primary goal is to stabilize blood sugar and improve insulin sensitivity. This can be achieved with a diet focused on a low glycemic load, which minimizes sharp spikes in blood glucose. This involves prioritizing non-starchy vegetables, lean proteins, and healthy fats while carefully managing the intake of carbohydrates, opting for high-fiber, complex sources. For some individuals, particularly those with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), dietary interventions have been shown to improve both metabolic and hormonal parameters.

- Exercise Programming for Hormonal Optimization A balanced exercise routine provides a spectrum of beneficial signals. Resistance training, performed 2-4 times per week, is a powerful stimulus for testosterone and growth hormone. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) can be a time-efficient way to improve insulin sensitivity, but it must be used judiciously to avoid over-stressing the HPA axis. Low-intensity steady-state cardio, like brisk walking, helps to manage cortisol and improve cardiovascular health without adding significant stress.

- Circadian Management Protocol This involves more than just getting enough sleep; it requires anchoring your body’s internal clock. This protocol includes ∞ aiming for 7-9 hours of sleep per night, maintaining a consistent wake-up time, getting direct sunlight exposure within the first hour of waking, and minimizing exposure to bright artificial light, especially from screens, in the 2-3 hours before bed. These actions reinforce the natural cortisol rhythm, which is foundational to all other hormonal cycles.

| Exercise Type | Primary Hormonal Effect | Key Benefits | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance Training | Increases Testosterone and Growth Hormone | Builds muscle mass, improves metabolic rate, enhances bone density. | Requires proper form to prevent injury; adequate recovery is essential. |

| High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) | Improves Insulin Sensitivity, increases catecholamines | Time-efficient cardiovascular conditioning, enhances fat oxidation. | Can be highly stressful on the HPA axis if overdone or during periods of high stress. |

| Aerobic/Endurance Training | Improves Insulin Sensitivity, moderates cortisol | Enhances cardiovascular health, reduces stress, improves mitochondrial function. | Excessive duration can elevate cortisol and suppress testosterone. |

When Lifestyle Is the Foundation for Clinical Support

Lifestyle changes can produce profound corrections in hormonal imbalances. For many, these interventions are sufficient to restore balance. However, in cases of significant age-related decline, such as andropause in men or menopause in women, or in certain clinical conditions, lifestyle changes alone may not be enough to restore hormone levels to an optimal range. In these scenarios, lifestyle modifications become the essential foundation upon which clinical protocols, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or other hormonal optimization strategies, are built.

A well-regulated system, supported by optimal nutrition, exercise, and sleep, will respond more effectively and safely to therapeutic interventions. The goal of these protocols is to restore the body’s internal environment to a state where it can once again function with vitality.

Academic

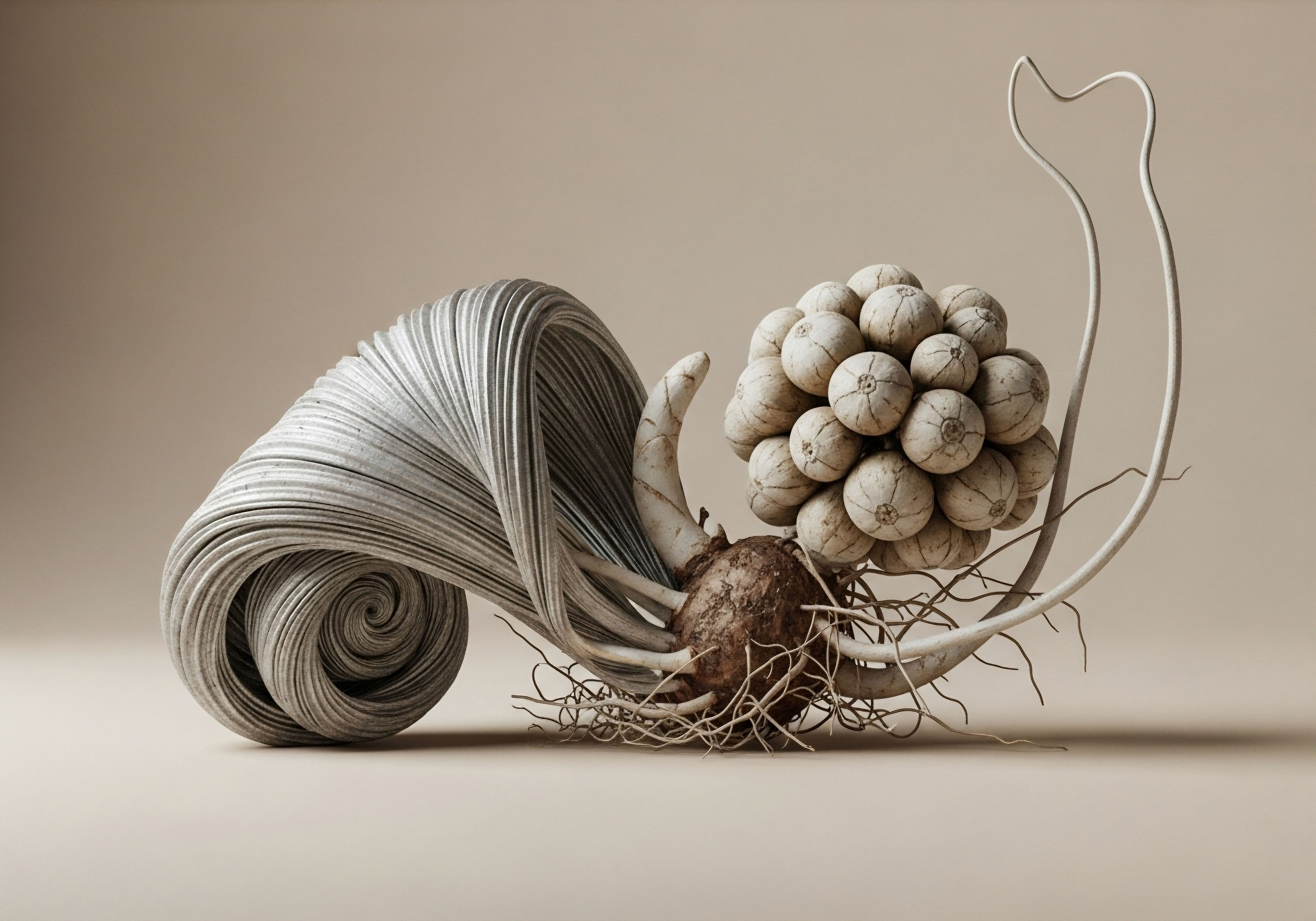

A sophisticated analysis of hormonal health requires moving beyond the primary endocrine axes to examine the complex interplay between disparate physiological systems. One of the most dynamic frontiers in endocrinology is the Gut-Hormone Axis, a bidirectional communication pathway linking the gastrointestinal microbiome to systemic hormonal regulation. Within this domain, the concept of the “estrobolome” offers a precise mechanistic explanation for how lifestyle factors, particularly diet, can directly modulate estrogen levels and contribute to either hormonal homeostasis or pathology. This provides a compelling, systems-biology perspective on correcting hormonal imbalances, particularly in estrogen-sensitive conditions.

The Estrobolome a Microbial Regulator of Estrogen

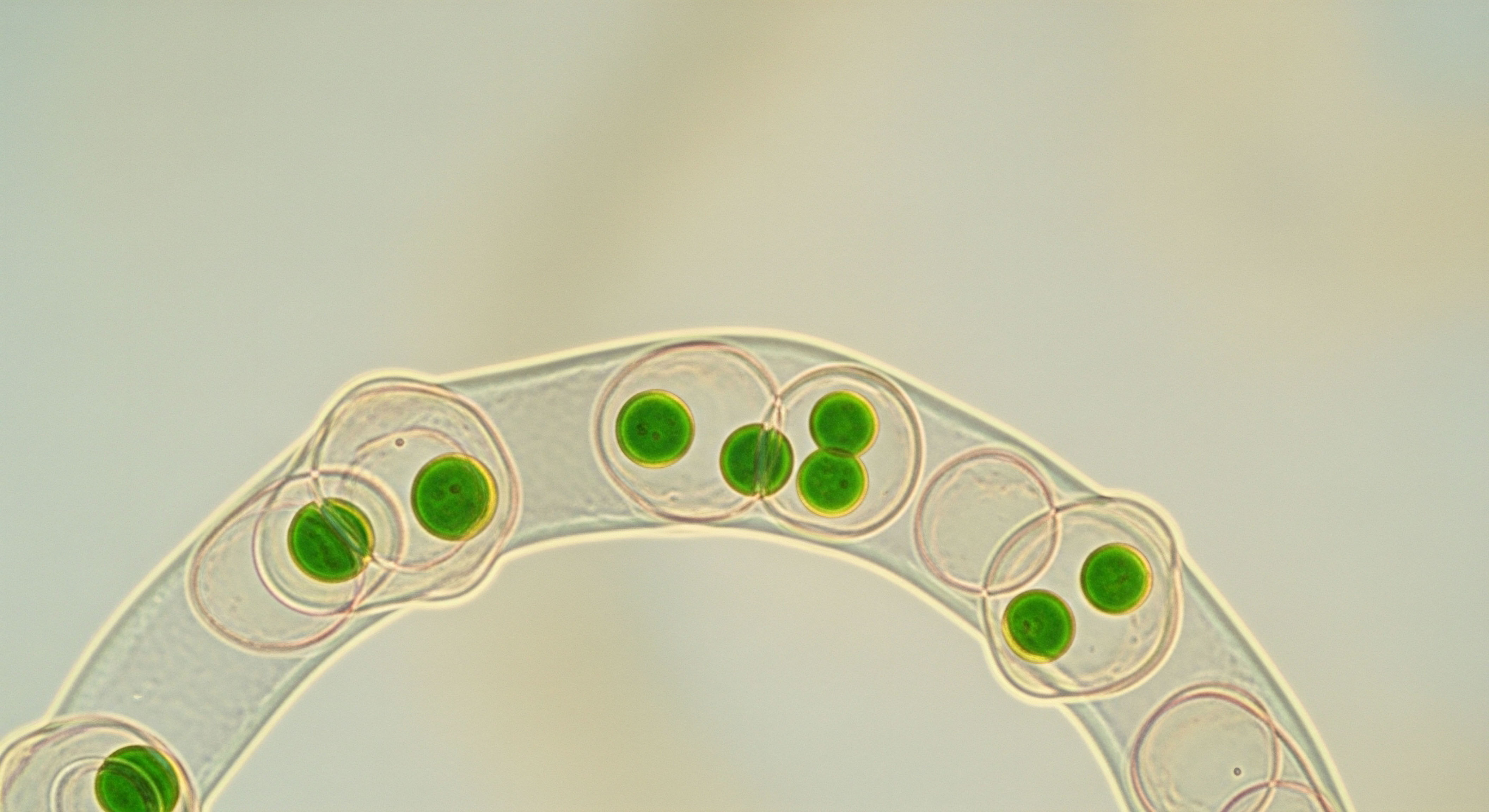

The term estrobolome Meaning ∞ The estrobolome refers to the collection of gut microbiota metabolizing estrogens. refers to the aggregate of bacterial genes within the gut microbiome Meaning ∞ The gut microbiome represents the collective community of microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, viruses, and fungi, residing within the gastrointestinal tract of a host organism. that are capable of metabolizing estrogens. Estrogens, primarily produced in the ovaries and adrenal glands, undergo metabolism in the liver. In a process called conjugation, the liver attaches a glucuronic acid molecule to the estrogen, rendering it inactive and water-soluble, preparing it for excretion. These conjugated estrogens are then secreted into the gut via bile.

Here, the estrobolome Meaning ∞ The estrobolome is the collection of gut bacteria that metabolize estrogens. plays a pivotal role. Certain gut bacteria, including species from the Bacteroides and Lactobacillus genera, produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. This enzyme can cleave the glucuronic acid molecule from the conjugated estrogen, a process known as deconjugation. This reverts the estrogen back to its active, unconjugated form, which can then be reabsorbed from the gut back into circulation. This entire process is known as the enterohepatic circulation Meaning ∞ Enterohepatic circulation describes the physiological process where substances secreted by the liver into bile are subsequently reabsorbed by the intestine and returned to the liver via the portal venous system. of estrogens.

How Does Gut Dysbiosis Influence Hormonal Balance?

The composition and health of the gut microbiome directly dictate the level of beta-glucuronidase activity Meaning ∞ Beta-glucuronidase activity denotes the catalytic action of the enzyme beta-glucuronidase, which hydrolyzes glucuronide bonds. and, consequently, the amount of estrogen that is recirculated. A state of gut dysbiosis—an imbalance in the microbial community—can significantly alter estrogen homeostasis. An overgrowth of beta-glucuronidase-producing bacteria can lead to increased deconjugation and reabsorption of estrogens, contributing to a state of estrogen dominance. This condition is implicated in a range of health issues, including premenstrual syndrome (PMS), endometriosis, and an increased risk of estrogen-receptor-positive cancers.

Conversely, a microbiome with low beta-glucuronidase Meaning ∞ Beta-glucuronidase is an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of glucuronides, releasing unconjugated compounds such as steroid hormones, bilirubin, and various environmental toxins. activity might lead to insufficient reabsorption and increased excretion of estrogens, potentially resulting in symptoms of estrogen deficiency. Therefore, the gut microbiome functions as a critical control knob for systemic estrogen levels.

The gut microbiome, through its metabolic actions, functions as a distinct and highly modifiable endocrine organ.

The implications for health are substantial. Modulating the gut microbiome through targeted lifestyle interventions presents a viable strategy for correcting estrogen-related imbalances. This approach moves beyond simply managing symptoms to addressing a root physiological driver of hormonal dysregulation. The bidirectional nature of this relationship is also noteworthy; estrogens themselves can influence the diversity of the gut microbiome, highlighting a complex feedback system that can be guided toward a healthier equilibrium.

Targeted Interventions to Modulate the Estrobolome

Lifestyle interventions, particularly dietary strategies, can be designed to specifically shape the estrobolome and optimize its function. These are not generic health recommendations; they are precise inputs aimed at cultivating a microbial environment conducive to hormonal balance.

- Dietary Fiber and Prebiotics ∞ Soluble and insoluble fibers from a wide variety of plant sources—such as vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains—are fermented by gut bacteria to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate. SCFAs help maintain the integrity of the gut lining and create an environment that favors the growth of beneficial bacteria, thereby helping to balance the microbial community and moderate beta-glucuronidase activity.

- Cruciferous Vegetables ∞ Vegetables like broccoli, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts contain a compound called indole-3-carbinol (I3C). In the gut, I3C is converted to diindolylmethane (DIM), which supports healthy estrogen metabolism pathways in the liver, complementing the work of the estrobolome.

- Probiotic-Rich Foods ∞ Fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, kimchi, and sauerkraut introduce beneficial bacterial species, such as Lactobacillus, which can help to competitively exclude pathogenic species and promote a more balanced gut ecosystem.

- Reducing Gut Disruptors ∞ A diet high in processed foods, sugar, and excessive alcohol can promote dysbiosis, feeding the types of bacteria that may lead to higher beta-glucuronidase activity. Chronic stress also negatively impacts the microbiome by altering gut motility and increasing intestinal permeability, which can lead to systemic inflammation and further disrupt hormonal signaling.

| Factor | Positive Influence (Supports Balance) | Negative Influence (Promotes Imbalance) |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Fiber | High intake from diverse plant sources; promotes SCFA production. | Low intake; starves beneficial microbes. |

| Dietary Fat | Omega-3 fatty acids (from fish, flax) have anti-inflammatory properties. | High intake of processed, pro-inflammatory fats. |

| Probiotics | Consumption of fermented foods or targeted probiotic supplements. | Lack of fermented foods in the diet. |

| Alcohol | Minimal to no consumption. | Excessive consumption promotes dysbiosis and burdens the liver. |

| Stress | Effective stress management techniques. | Chronic stress leading to increased cortisol and gut permeability. |

This deep biological connection illustrates that lifestyle interventions are a form of targeted therapy. They are not passive wellness activities; they are active modulators of the complex systems that determine hormonal health. By focusing on cultivating a healthy gut microbiome, one can directly influence the estrobolome and, by extension, achieve a more favorable and balanced hormonal state. This is a prime example of how understanding deep physiological mechanisms empowers individuals to make choices that have a profound and measurable impact on their health.

References

- Volek, Jeff S. et al. “Testosterone and Cortisol in Relationship to Dietary Nutrients and Resistance Exercise.” Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 82, no. 1, 1997, pp. 49-54.

- Hirotsu, C. Tufik, S. & Andersen, M. L. “Interactions between sleep, stress, and metabolism ∞ From physiological to pathological conditions.” Sleep Science, vol. 8, no. 3, 2015, pp. 143-152.

- Baker, J. M. Al-Nakkash, L. & Herbst-Kralovetz, M. M. “Estrogen-gut microbiome axis ∞ Physiological and clinical implications.” Maturitas, vol. 103, 2017, pp. 45-53.

- Whitten, P. L. & Naftolin, F. “Reproductive actions of phytoestrogens.” Baillière’s Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 12, no. 4, 1998, pp. 667-691.

- Moran, L. J. et al. “Lifestyle changes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 7, 2011.

- Kwa, M. Plottel, C. S. Blaser, M. J. & Adams, S. “The Intestinal Microbiome and Estrogen Receptor-Positive Female Breast Cancer.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 108, no. 8, 2016.

- Ranabir, S. & Reetu, K. “Stress and hormones.” Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 15, no. 1, 2011, pp. 18-22.

- Vgontzas, A. N. et al. “Sleep deprivation effects on the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and growth axes ∞ potential clinical implications.” Clinical Endocrinology, vol. 51, no. 2, 1999, pp. 205-15.

- Riachy, R. et al. “Various Factors May Modulate the Effect of Exercise on Testosterone Levels in Men.” Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, vol. 5, no. 4, 2020, p. 81.

Reflection

You began this exploration with a set of numbers on a page and a feeling in your body. You now possess a deeper map of the internal landscape those numbers represent—the intricate axes, the feedback loops, the profound influence of the microbial world within you. This knowledge is the first and most critical tool for change.

It transforms the act of eating, moving, and sleeping from daily routine into a conscious dialogue with your own physiology. You are now equipped to ask more specific questions and to observe the outcomes of your choices with greater clarity.

Consider your own daily inputs. Where are your signals strongest? Where might they be creating static or interference in your internal communication network? This journey of recalibration is deeply personal.

The path to restoring your vitality is one of self-discovery, guided by an understanding of your unique biology. The information presented here is a framework, a way of thinking about your health that places the power of daily action in your hands. The ultimate goal is to move from a state of reacting to symptoms to proactively cultivating the biological environment that allows you to function with uncompromising energy and well-being. This understanding is the foundation for any successful health strategy, whether it is pursued through lifestyle alone or in partnership with targeted clinical support.