Fundamentals

You feel it as a dissonance, a conflict within your own biology. Your body, this vessel for your life’s experience, seems to be operating from a different set of instructions. The question of whether lifestyle changes alone can completely normalize androgen levels in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a profound one.

It moves past a simple desire for symptom relief and touches upon a deeper yearning to restore your body’s innate physiological harmony. It is a question about reclaiming a sense of self, of predictable function, and of internal peace.

The answer is found not in a simple affirmative or negative, but in understanding the elegant, interconnected systems that govern your health. This is a journey of biological self-discovery, one that empowers you to become an active participant in the recalibration of your own endocrine system.

At the center of this conversation are two powerful biological communicators ∞ insulin and androgens. In the context of PCOS, these hormones are engaged in a complex, cyclical dialogue. Insulin, the hormone responsible for managing glucose from your bloodstream, is a master regulator of energy.

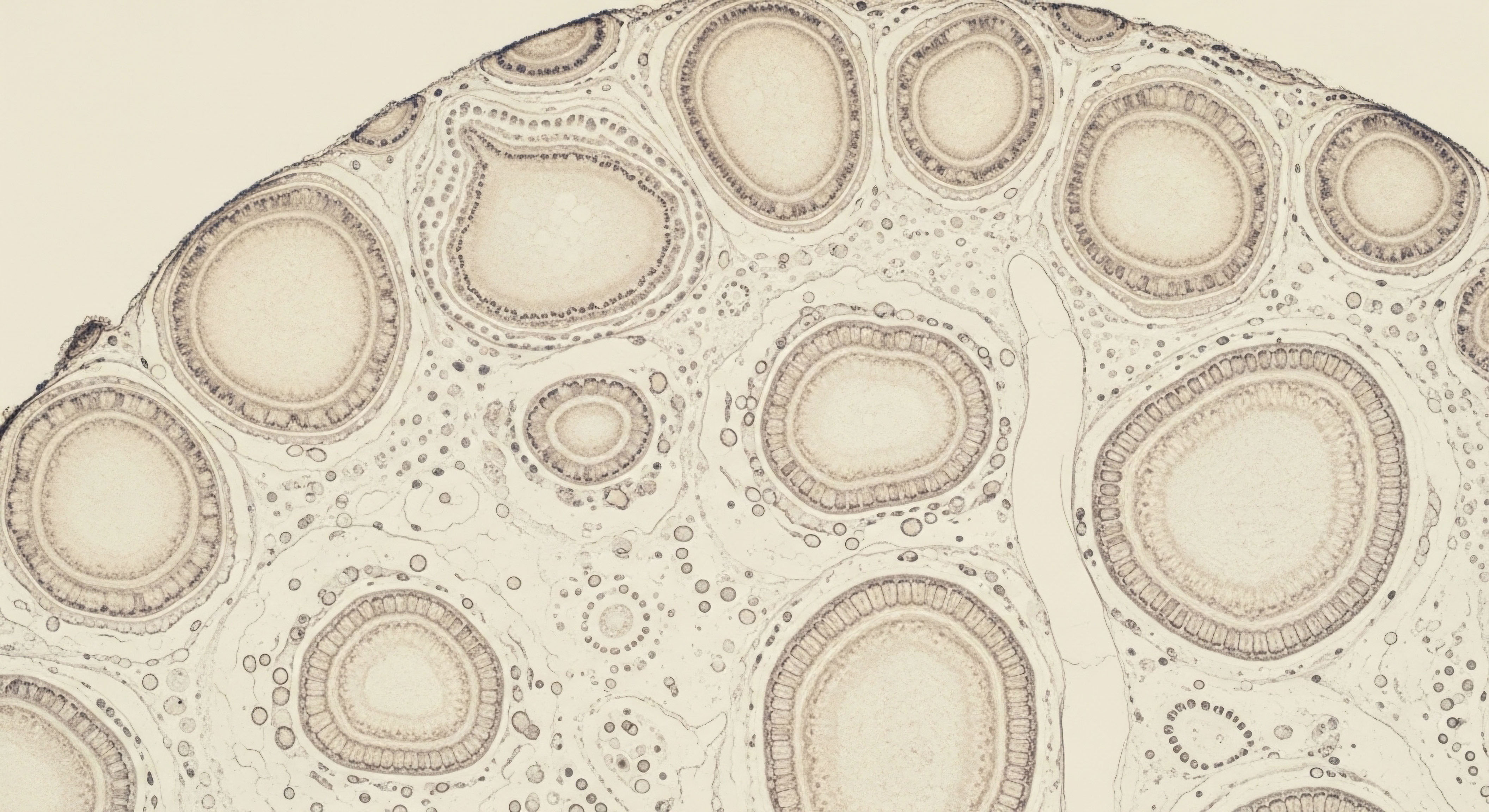

Androgens, such as testosterone, are steroid hormones that influence a wide array of bodily functions. In many women with PCOS, the cells of the body become less responsive to insulin’s signals. This state, known as insulin resistance, prompts the pancreas to produce ever-increasing amounts of insulin to get the job done.

This cascade of elevated insulin has a direct effect on the ovaries, stimulating them to produce higher levels of androgens. This is the primary biological mechanism that connects your metabolism to your reproductive hormones.

Understanding the interplay between insulin and androgens is the first step toward managing the metabolic and hormonal imbalances of PCOS.

This biochemical environment, characterized by elevated insulin and androgens, gives rise to the symptoms you experience. The communication breakdown is systemic. It affects the regularity of your menstrual cycle, the health of your skin and hair, and your body’s ability to manage weight. Recognizing this allows you to reframe your experience.

The symptoms are not isolated problems; they are signals from a system under strain. They are downstream effects of an upstream cause. Therefore, the path to normalizing function involves addressing the root of this disturbance. Lifestyle modifications are powerful because they directly target the primary driver of the imbalance ∞ insulin resistance. By changing how you fuel and move your body, you can fundamentally alter the biochemical conversation happening within you.

The Concept of Hormonal Balance

Hormonal balance is a dynamic process, a continuous adjustment to internal and external cues. Your endocrine system functions like a finely tuned orchestra, with each hormone playing its part at the precise volume and time. In PCOS, it is as if the brass section, the androgens, is playing too loudly, prompted by an overzealous conductor, insulin.

The goal of lifestyle intervention is to gently guide that conductor back to the original score. This involves creating a physiological environment that allows your cells to become more sensitive to insulin again. When insulin levels can decrease, the excessive stimulation of the ovaries is reduced. In response, androgen production begins to downregulate.

This is how the system is designed to function. Your body possesses the innate capacity for self-regulation; the work of lifestyle change is to remove the obstacles that are preventing it from doing so.

Why Lifestyle Is the Foundation

Medical interventions can be effective tools, yet they often work by interrupting a specific pathway or providing an external source of a hormone. Lifestyle interventions, conversely, work by restoring the body’s own ability to regulate itself. They are foundational because they address the underlying metabolic dysfunction that initiates and perpetuates the hormonal imbalance.

A diet that minimizes sharp spikes in blood sugar reduces the demand for insulin. Regular physical activity enhances the sensitivity of your muscle cells to insulin, allowing them to take up glucose more efficiently. Managing stress and prioritizing sleep helps to regulate cortisol, another hormone that can influence insulin resistance.

These actions collectively create a powerful, synergistic effect that quiets the excessive hormonal noise, allowing for clearer communication between your body’s intricate systems. This is the essence of reclaiming your vitality. It is a process of providing your body with the inputs it needs to perform its functions with grace and efficiency.

Intermediate

To truly grasp the potential of lifestyle interventions in managing PCOS, we must move from foundational concepts to the specific biological mechanisms at play. The question of achieving complete normalization of androgens is a question of degree. For many individuals, strategic and sustained lifestyle changes can lower androgen levels to a point where clinical symptoms resolve and metabolic health is restored.

This process is about systematically changing the inputs to your biological system to achieve a more favorable output. It involves a targeted approach to diet, a specific application of exercise, and a conscious regulation of the body’s stress response systems. Each of these pillars works on distinct yet overlapping pathways that converge on the central hub of insulin sensitivity and androgen production.

Dietary Protocols for Hormonal Recalibration

The food you consume is not merely a source of calories; it is a source of information that directly influences hormonal signaling. The primary dietary strategy for managing PCOS revolves around controlling insulin secretion. This is most effectively achieved through a focus on the glycemic index (GI) and glycemic load (GL) of your meals.

The Low Glycemic Approach

A low-glycemic diet prioritizes foods that are digested and absorbed slowly, leading to a gradual and lower rise in blood glucose and insulin levels. This approach directly addresses the hyperinsulinemia that drives ovarian androgen production. When you consume high-glycemic carbohydrates (like sugary drinks, white bread, and processed snacks), they cause a rapid surge in blood glucose.

The pancreas responds by releasing a large amount of insulin. In a state of insulin resistance, this response is exaggerated. This flood of insulin travels to the ovaries and stimulates the theca cells to synthesize and secrete androgens. A low-glycemic diet interrupts this cycle.

By choosing complex carbohydrates rich in fiber, such as legumes, whole grains, and non-starchy vegetables, you provide your body with a steady supply of energy that does not provoke an excessive insulin response. This, in turn, reduces the androgen-promoting signal to the ovaries.

Furthermore, stable insulin levels help increase the production of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) in the liver. SHBG binds to testosterone in the bloodstream, rendering it inactive. Higher SHBG levels mean less free testosterone is available to cause symptoms like hirsutism and acne.

Anti Inflammatory Nutrition

Chronic low-grade inflammation is another key feature of PCOS. This inflammatory state can contribute to insulin resistance and directly stimulate the ovaries to produce androgens. An anti-inflammatory diet, therefore, is a powerful complementary strategy. This involves increasing your intake of foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids, such as fatty fish (salmon, mackerel, sardines), walnuts, and chia seeds.

These fats are incorporated into cell membranes and can shift the production of signaling molecules towards less inflammatory pathways. Colorful fruits and vegetables are rich in antioxidants and polyphenols, which combat oxidative stress, a byproduct of inflammation. Spices like turmeric and ginger also contain potent anti-inflammatory compounds. By actively reducing the body’s inflammatory burden, you create an internal environment that is more conducive to both insulin sensitivity and balanced hormone production.

The table below outlines a comparison of dietary approaches and their primary mechanisms of action in the context of PCOS.

| Dietary Approach | Primary Mechanism | Key Foods | Impact on Androgens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Glycemic Index Diet | Reduces post-meal insulin spikes, mitigating the primary stimulus for ovarian androgen production. | Legumes, whole grains, nuts, seeds, non-starchy vegetables, berries. | Directly lowers the insulin signal to the ovaries and can increase SHBG, reducing free testosterone. |

| Mediterranean Diet | Combines low-glycemic eating with a high intake of anti-inflammatory fats and antioxidants. | Olive oil, fatty fish, nuts, seeds, vegetables, fruits, whole grains. | Reduces inflammation-induced insulin resistance and provides essential fatty acids for hormone synthesis. |

| DASH Diet | Focuses on whole foods, minerals like potassium and magnesium, and limiting sodium to improve blood pressure and insulin sensitivity. | Fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, low-fat dairy, whole grains, nuts. | Improves overall metabolic health, which indirectly supports healthier androgen levels through enhanced insulin function. |

How Does Exercise Influence Androgen Levels?

Physical activity is a potent modulator of insulin sensitivity and hormonal balance. Different forms of exercise offer unique benefits, and a combination is often most effective. The goal of an exercise protocol for PCOS is to improve the body’s ability to handle glucose, thereby reducing the need for excess insulin.

Aerobic Exercise

Activities like brisk walking, running, cycling, and swimming improve cardiovascular health and have a profound impact on insulin sensitivity. During aerobic exercise, your muscles increase their uptake of glucose from the bloodstream, a process that can occur even without high levels of insulin.

Regular aerobic training makes your muscle cells more sensitive to insulin in the long term. This means that after a meal, less insulin is required to clear glucose from your blood. This reduction in circulating insulin is key to lowering androgen production. Studies have shown that consistent, moderate-to-vigorous aerobic exercise can lead to significant reductions in testosterone concentrations in women with PCOS.

Resistance Training

Lifting weights or performing bodyweight exercises like squats and push-ups builds muscle mass. Muscle is your body’s largest storage site for glucose. The more muscle mass you have, the more glucose you can store as glycogen, and the more efficient your body becomes at managing blood sugar.

After a resistance training session, your muscles are highly receptive to taking up glucose to replenish their stores. This enhanced glucose disposal helps to lower overall insulin levels. Resistance training has also been shown to improve body composition by increasing lean mass and reducing fat mass, which further contributes to improved insulin sensitivity. For women with PCOS, this form of exercise is a powerful tool for building a more metabolically flexible body.

A combination of aerobic and resistance exercise provides a comprehensive strategy for improving insulin sensitivity and reducing androgen levels.

The Stress Cortisol Connection

The body’s stress response system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, is intricately linked to the reproductive system. Chronic stress, whether psychological or physiological, leads to sustained high levels of the hormone cortisol. Elevated cortisol can directly promote insulin resistance by increasing the amount of glucose released into the bloodstream.

It can also disrupt the signaling within the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, which governs reproductive hormone production. This can lead to irregular cycles and can exacerbate the hormonal imbalances of PCOS. Therefore, practices that manage stress are a non-negotiable component of a comprehensive lifestyle plan.

These can include mindfulness meditation, yoga, deep breathing exercises, and ensuring adequate, high-quality sleep. By regulating the HPA axis, you create a more stable internal environment that supports the healthy function of all other hormonal systems.

- Mindfulness and Meditation ∞ These practices have been shown to lower cortisol levels and reduce the perception of stress, thereby mitigating its negative impact on insulin sensitivity.

- Yoga and Tai Chi ∞ These mind-body practices combine movement, breathing, and meditation, offering benefits for both stress reduction and physical fitness.

- Sleep Hygiene ∞ Sleep deprivation is a significant physiological stressor that can impair insulin sensitivity and disrupt reproductive hormones. Prioritizing 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night is essential for hormonal regulation.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of whether lifestyle modifications can “completely normalize” androgen levels in PCOS requires a departure from binary outcomes and an immersion into the quantitative and qualitative aspects of endocrine function. The term “normalization” itself warrants scrutiny.

Does it mean returning androgen levels to the statistical mean of a population without PCOS, or does it signify a reduction sufficient to restore ovulatory function and resolve the clinical signs of hyperandrogenism? From a clinical perspective, the latter is the more salient objective.

The evidence from numerous clinical trials and meta-analyses suggests that while lifestyle intervention is the most potent non-pharmacological tool for reducing hyperandrogenism, the degree of normalization is heterogeneous and contingent upon baseline phenotype, genetic predispositions, and the fidelity of the intervention. The core of the issue lies in the intricate, self-perpetuating feedback loops between insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and ovarian and adrenal androgen production.

The Molecular Dialogue between Insulin and the Ovary

The pathophysiology of hyperandrogenism in PCOS is fundamentally linked to a dysregulation in the insulin signaling pathway. In ovarian theca cells, insulin does not just regulate glucose metabolism; it acts as a co-gonadotropin, synergizing with Luteinizing Hormone (LH) to stimulate androgen synthesis. Under normal physiological conditions, this effect is modest.

However, in the context of systemic insulin resistance and the resultant compensatory hyperinsulinemia, this pathway becomes chronically overstimulated. Insulin binds to its own receptor on theca cells, but also to the receptor for Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1), to which it has a lower affinity. The chronically high levels of insulin seen in PCOS effectively saturate these receptors, leading to a potentiation of the steroidogenic cascade.

This stimulation upregulates the expression of key enzymes involved in androgen production, most notably P450c17. This enzyme possesses both 17α-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase activity, which are critical rate-limiting steps in the conversion of pregnenolone and progesterone into androgens like DHEA and androstenedione. These are then converted to testosterone.

Lifestyle interventions, particularly those focused on diet and exercise, directly target this mechanism by reducing the primary stimulus ∞ insulin. A meta-analysis of lifestyle interventions demonstrated a significant reduction in total testosterone, androstenedione, and the Free Androgen Index (FAI). The FAI, which is a calculation based on total testosterone and SHBG, is a particularly sensitive marker of bioactive testosterone.

The improvement in FAI is a dual effect of lifestyle modification ∞ not only does it reduce total testosterone production, but by improving insulin sensitivity, it also allows the liver to increase its production of SHBG. This increase in SHBG effectively binds more testosterone, further reducing the fraction that is free to exert its effects on target tissues.

Can Lifestyle Interventions Fully Correct the Intrinsic Theca Cell Dysregulation?

This is a central question in the academic discourse. Some research suggests that theca cells from women with PCOS have an intrinsic, perhaps genetically programmed, hypersecretory capacity for androgens, independent of the insulin environment.

If this is the case, then lifestyle interventions, while profoundly effective at removing the exacerbating factor of hyperinsulinemia, may not be able to “completely normalize” androgen production if the baseline secretory activity is inherently elevated. This could explain the heterogeneity of responses seen in clinical trials.

For a woman with a milder phenotype and whose hyperandrogenism is largely driven by insulin resistance, lifestyle changes alone might be sufficient to bring androgen levels into the normal reference range and restore all physiological function.

For a woman with a more severe, genetically rooted form of theca cell dysfunction, lifestyle changes would still be critically important for reducing her androgen burden and managing metabolic comorbidities, but she might require pharmacological support to achieve a complete biochemical normalization.

A study on obese adolescent girls with PCOS demonstrated that a one-year lifestyle intervention led to significant decreases in testosterone and increases in SHBG in the group that achieved weight loss, underscoring the powerful effect of addressing the metabolic component.

The following table presents data synthesized from a meta-analysis, illustrating the quantitative impact of lifestyle interventions on key hormonal parameters in women with PCOS.

| Hormonal Parameter | Mean Difference with Lifestyle Intervention | 95% Confidence Interval | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Testosterone | -0.13 nmol/L | -0.22 to -0.03 | A statistically significant reduction in the primary circulating androgen. |

| Androstenedione | -0.09 ng/dL | -0.15 to -0.03 | A significant decrease in a key precursor to testosterone. |

| Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) | +2.37 nmol/L | +1.27 to +3.47 | A significant increase, leading to less biologically active free testosterone. |

| Free Androgen Index (FAI) | -1.64 | -2.94 to -0.35 | A significant improvement, reflecting a reduction in both androgen production and bioavailability. |

The Systemic View Inflammation and the Adrenal Component

The conversation about androgens in PCOS often centers on the ovaries, but the adrenal glands are also contributors. While lifestyle changes have a more pronounced and direct effect on ovarian androgen production via the insulin pathway, they can also influence adrenal androgen output.

Chronic stress and inflammation, both of which are addressed by comprehensive lifestyle programs, can modulate adrenal function. By reducing the systemic inflammatory load and regulating the HPA axis through stress management and adequate sleep, it is possible to temper the adrenal contribution to the total androgen pool.

This systems-biology perspective is essential. The endocrine system is a network. A perturbation in one area creates ripple effects elsewhere. Likewise, an intervention that supports one part of the network can create positive, stabilizing effects throughout. Lifestyle modification is powerful because it is a systemic intervention.

It does not target a single molecule but rather shifts the entire physiological environment towards one of homeostasis and efficiency. The extent to which this systemic shift can achieve “complete normalization” is a testament to the body’s remarkable plasticity and its inherent drive toward equilibrium.

- Weight Loss as a Mediator ∞ A modest weight loss of 5-10% of body weight has been consistently shown to be a powerful mediator of the benefits of lifestyle intervention. It improves insulin sensitivity, reduces inflammatory markers, and leads to significant reductions in androgen levels.

- The Role of Exercise Intensity ∞ Some evidence suggests that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) may be particularly effective at improving insulin sensitivity and body composition in women with PCOS, offering a time-efficient and potent exercise strategy.

- Long-Term Adherence ∞ The ultimate success of lifestyle intervention is contingent upon long-term, sustainable changes. The concept of “normalization” is not a one-time achievement but a continuous state maintained by consistent behaviors. The challenge lies in creating habits that can be integrated into an individual’s life indefinitely.

References

- Teede, H. J. Misso, M. L. Costello, M. F. Dokras, A. Laven, J. Moran, L. Piltonen, T. & Norman, R. J. (2018). Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction, 33 (9), 1602 ∞ 1618.

- Kite, C. Lahart, I. Afzal, I. Broom, D. Randeva, H. Kyrou, I. & Brown, J. (2019). Exercise, or exercise and diet for the management of polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic Reviews, 8 (1), 51.

- Jensterle, M. Kocjan, T. Pfeifer, M. & Janez, A. (2011). Effect of lifestyle intervention on features of polycystic ovarian syndrome, metabolic syndrome, and intima-media thickness in obese adolescent girls. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 96 (11), 3480 ∞ 3488.

- Moran, L. J. Hutchison, S. K. Norman, R. J. & Teede, H. J. (2011). Lifestyle changes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (7).

- Haqq, L. McFarlane, J. & Dieberg, G. (2014). The effect of lifestyle intervention on the reproductive endocrine profile in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine Connections, 3 (2), R53 ∞ R64.

- Legro, R. S. Arslanian, S. A. Ehrmann, D. A. Hoeger, K. M. Murad, M. H. Pasquali, R. & Welt, C. K. (2013). Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 98 (12), 4565 ∞ 4592.

- Shaikh, N. Dadachanji, R. & Mukherjee, S. (2014). Genetic markers of polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ a systematic review. Reproductive BioMedicine Online, 29 (4), 499-519.

- Asemi, Z. Esmaillzadeh, A. (2015). DASH diet, insulin resistance, and serum hs-CRP in polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ a randomized controlled clinical trial. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 66 (2-3), 169-175.

Reflection

You have now explored the biological architecture of PCOS, from the foundational interplay of hormones to the specific molecular conversations that occur within your cells. This knowledge is more than a collection of facts; it is a map.

It illuminates the pathways through which your daily choices ∞ the food you eat, the way you move, the rest you take ∞ become the chemical signals that orchestrate your internal world. The journey of managing PCOS is deeply personal.

The clinical data provides the principles, the ‘what’ and the ‘why’, but you are the one who translates this science into the lived reality of your own life. Consider the information presented here not as a rigid prescription, but as a set of tools. Which tool feels most accessible to you right now?

Where can you begin to make a small, sustainable shift that feels empowering? The path forward is one of partnership with your body, a process of listening to its signals and responding with intention and care. Your biology has a profound capacity for adaptation and healing. The work ahead is to create the conditions that allow that capacity to flourish.