Fundamentals

That feeling of staring at the ceiling at 3 a.m. your mind racing while your body aches for rest, is a deeply personal and frustrating experience. You have likely been told to try sleeping earlier, to put your phone away, or to drink herbal tea.

While well-intentioned, this advice often fails to acknowledge a powerful, invisible force orchestrating your sleep or lack thereof ∞ your endocrine system. The question of whether lifestyle changes alone can correct hormonally driven sleep problems is a journey into the very communication network of your body.

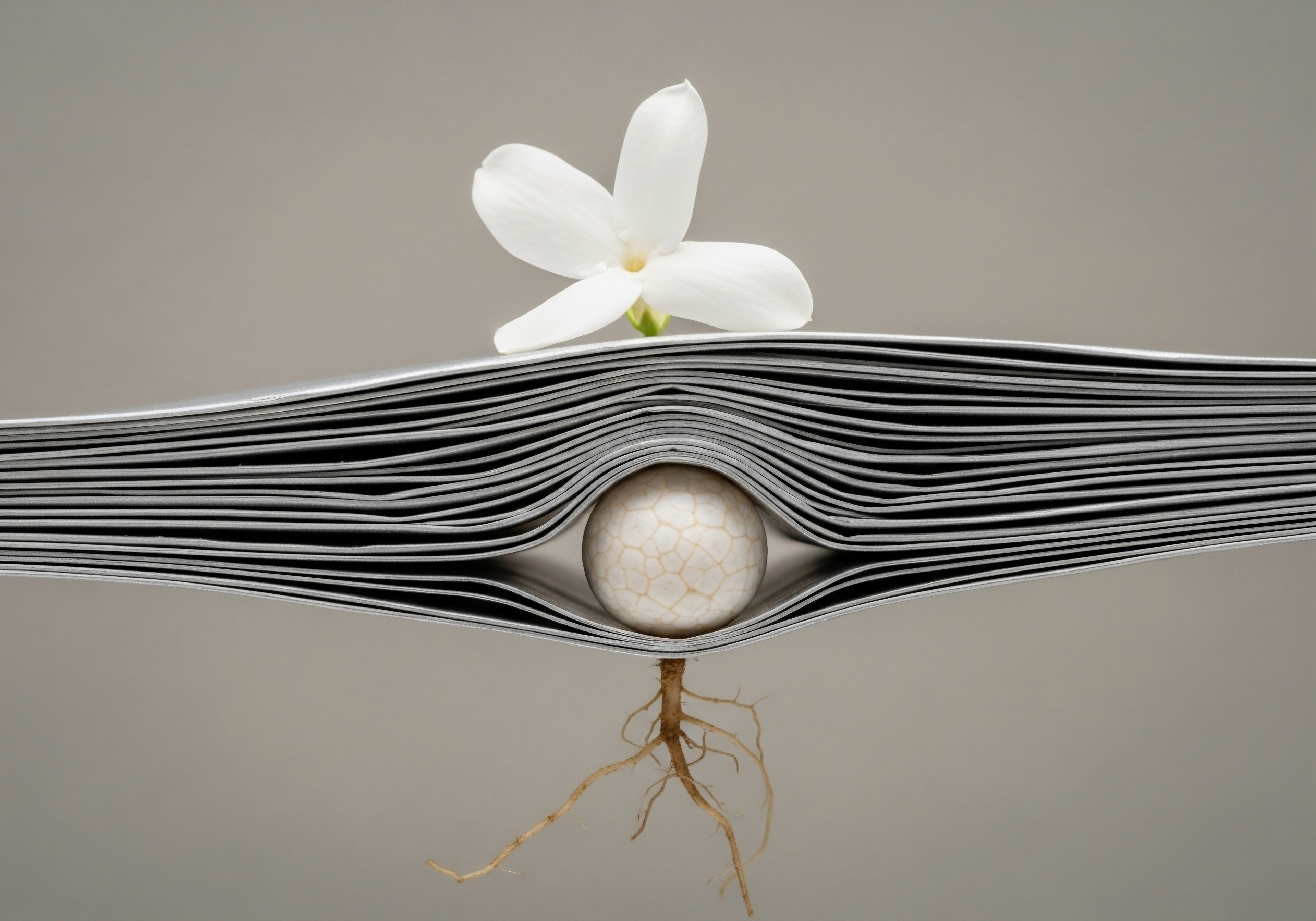

The answer begins with understanding that your sleep is a direct reflection of your internal hormonal symphony. When the key musicians ∞ your hormones ∞ are out of tune, no amount of quiet reverence in the concert hall can fix the sound.

Your body’s internal clock, the circadian rhythm, is conducted by two primary hormones ∞ melatonin and cortisol. Think of them as the yin and yang of your daily cycle. As darkness falls, your brain’s pineal gland is cued to release melatonin, the hormone that signals it is time for rest.

Melatonin lowers body temperature and gently ushers you toward sleep. Conversely, as morning approaches, your adrenal glands produce cortisol. This vital hormone should peak shortly after you wake, providing the energy and alertness needed to start your day. These two hormones exist in a delicate, inverse relationship.

When one is high, the other should be low. A disruption in this finely tuned rhythm is a primary driver of sleep disturbances. For instance, chronic stress can lead to elevated cortisol levels at night, effectively blocking melatonin’s sleep-promoting signals and leaving you feeling wired and awake when you should be winding down.

The Influence of Sex Hormones on Sleep

Beyond the primary sleep-wake regulators, your sex hormones play a profound role in sleep quality, particularly for women. Estrogen and progesterone are significant players in sleep architecture. Estrogen helps to regulate the body’s internal thermostat and supports the neurotransmitters that promote restful sleep. Progesterone has a naturally calming, sedative-like effect.

During perimenopause and menopause, the decline and fluctuation of these hormones can lead to significant sleep disruptions. The classic symptom of night sweats is a direct result of estrogen withdrawal affecting temperature regulation. The loss of progesterone’s calming influence can contribute to anxiety and difficulty staying asleep.

In men, testosterone is a key modulator of sleep quality. Healthy testosterone levels are associated with better sleep efficiency and more time spent in deep, restorative sleep stages. A bidirectional relationship exists here; low testosterone can contribute to poor sleep, and conversely, sleep deprivation has been shown to significantly lower testosterone levels in healthy young men.

This can create a downward spiral where poor sleep worsens hormonal balance, which in turn further degrades sleep. Conditions like sleep apnea are also closely linked to testosterone levels, with obesity often being a mediating factor.

Your ability to fall and stay asleep is directly governed by the rhythmic rise and fall of key hormones like melatonin and cortisol.

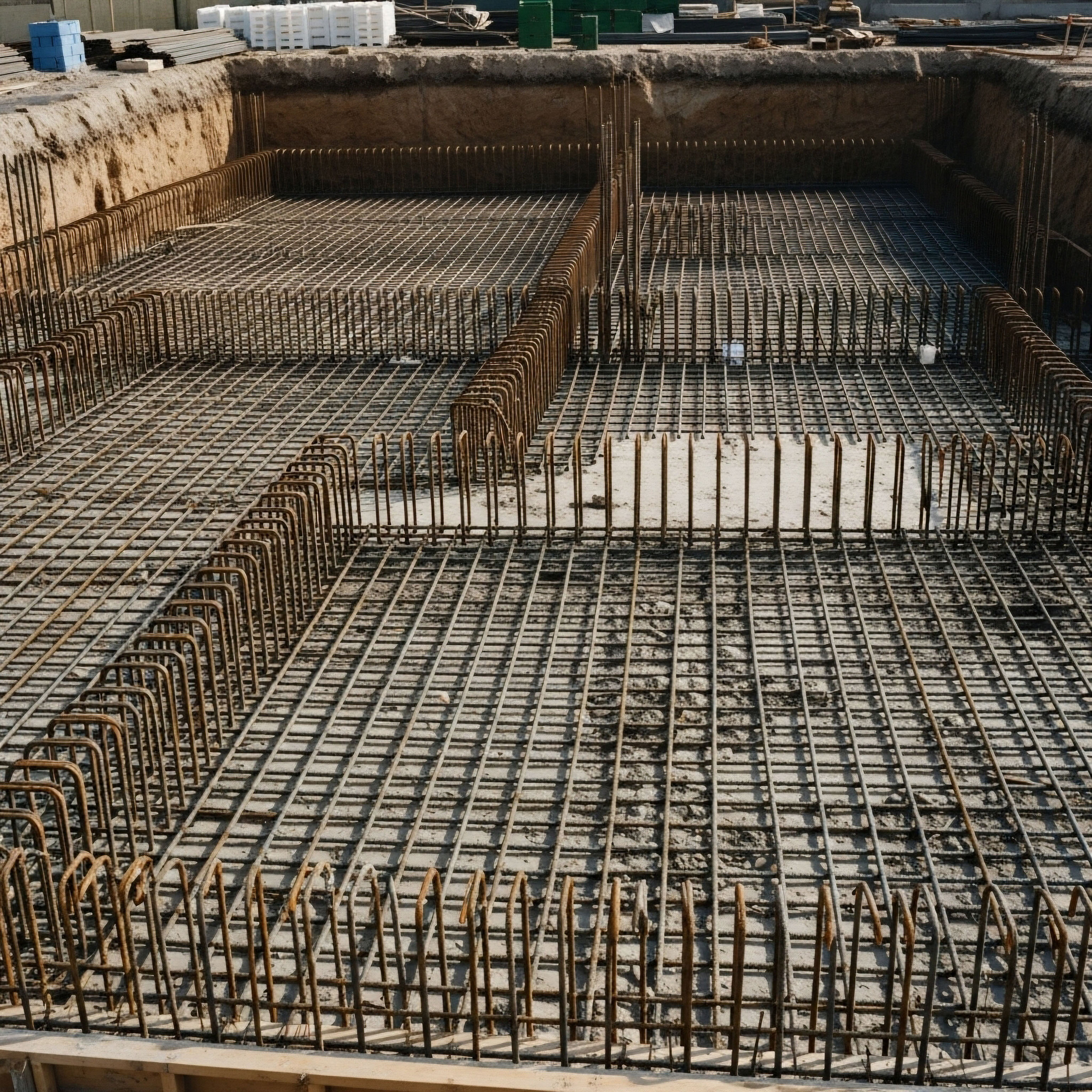

Lifestyle interventions are the foundational tools for influencing this hormonal orchestra. They are the equivalent of tuning the instruments before the performance begins. Consistent sleep schedules, mindful nutrition, regular physical activity, and strategic light exposure are powerful levers that can help resynchronize your internal clocks.

A diet high in refined sugars and saturated fats can increase cortisol levels, while a diet rich in whole foods, fiber, and healthy fats supports a healthier gut microbiome, which is linked to better mental health and stress reduction.

Similarly, exposure to bright light in the morning helps to properly set your cortisol peak, while limiting blue light from screens at night allows melatonin to rise unimpeded. These practices are not merely suggestions for healthy living; they are direct inputs into your endocrine system, capable of producing significant positive changes in your hormonal environment and, consequently, your sleep.

Intermediate

Understanding that hormones govern sleep is the first step. The next is to appreciate how specific lifestyle choices function as potent biochemical signals that directly modulate the endocrine system. These are not passive habits; they are active interventions.

When you engage in these practices, you are communicating with your body in the language of physiology, providing the necessary cues to recalibrate the intricate feedback loops that have gone awry. The effectiveness of these changes hinges on their ability to influence the primary hormonal axes that regulate your sleep-wake cycle and stress response.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis and Sleep

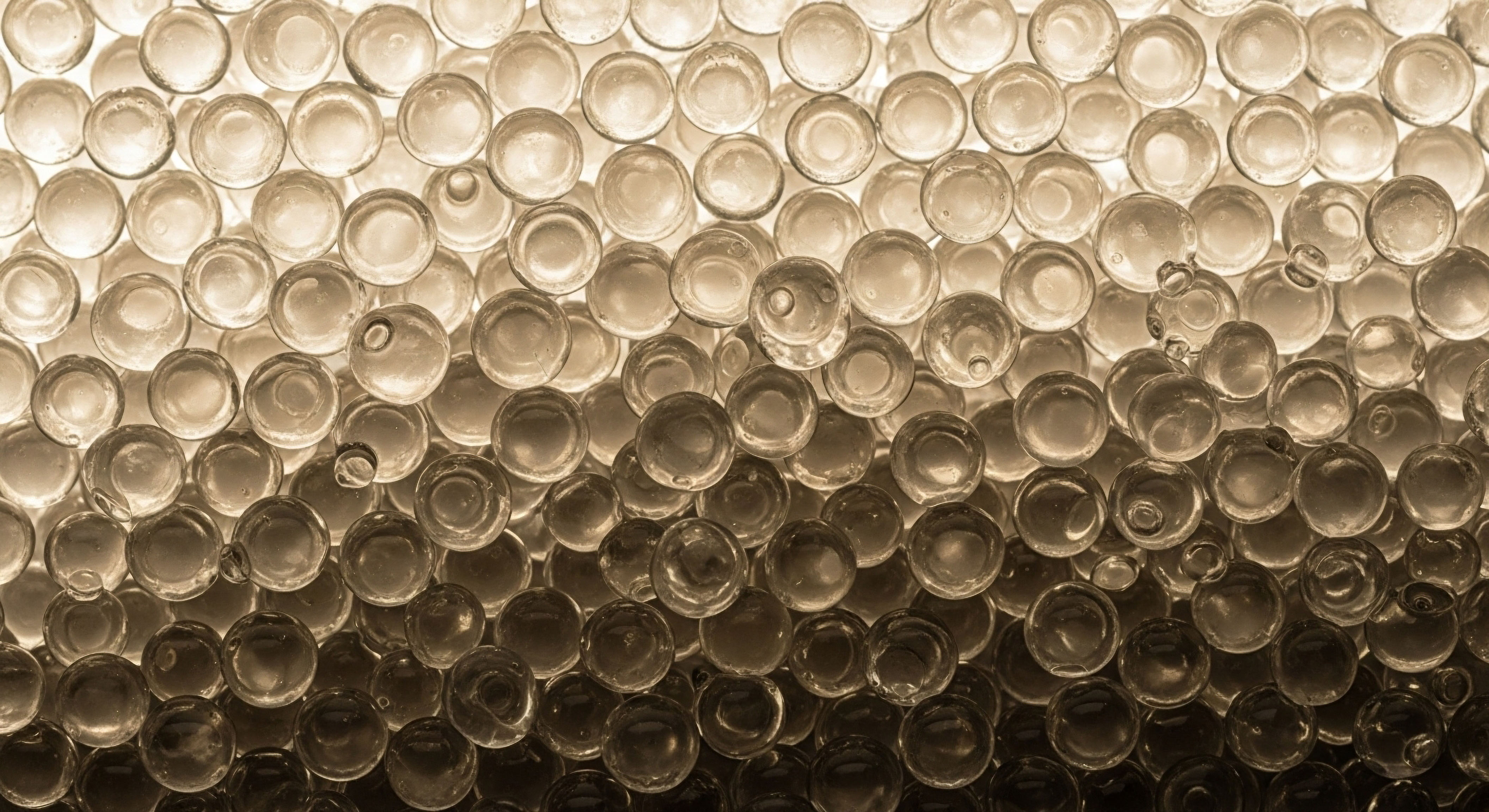

At the heart of the connection between stress and sleep lies the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. This neuroendocrine system is your body’s central stress response command center. When your brain perceives a threat, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which signals the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

ACTH then travels to the adrenal glands and stimulates the release of cortisol. In a healthy individual, this system activates in short bursts and is governed by a negative feedback loop; once cortisol levels are sufficient, the hypothalamus and pituitary gland halt the signal.

Chronic stress, whether from psychological pressure, poor diet, or lack of sleep itself, leads to HPA axis dysregulation. The system becomes hyperactive, leading to elevated cortisol levels, especially at night when they should be at their lowest. This hyperactivity directly interferes with sleep initiation and maintenance. Lifestyle interventions are powerful tools for down-regulating an overactive HPA axis.

- Mindfulness and Breathwork ∞ Practices like meditation and deep, slow breathing have been shown to directly activate the parasympathetic nervous system, the body’s “rest and digest” state. This activation helps to inhibit the HPA axis, reducing the production of cortisol and creating a physiological environment conducive to sleep.

- Strategic Exercise ∞ Regular physical activity is a beneficial stressor that can improve HPA axis function over time. Morning or early afternoon exercise can help reinforce the natural cortisol rhythm, leading to a more robust morning peak and a healthier decline in the evening. Intense exercise too close to bedtime, however, can elevate cortisol and interfere with sleep.

- Nutritional Support ∞ Your diet provides the building blocks for hormones and neurotransmitters. A diet that stabilizes blood sugar is crucial for HPA axis health. High-glycemic meals can cause spikes and crashes in blood sugar, which the body perceives as a stressor, triggering cortisol release. Conversely, a diet rich in complex carbohydrates, protein, and healthy fats provides a steady supply of energy and reduces the burden on the HPA axis.

How Does Nutrition Specifically Impact Sleep Hormones?

The foods you consume have a direct and measurable impact on the hormones that regulate sleep. A thoughtful nutritional strategy can be one of the most effective lifestyle interventions for improving hormonally driven sleep problems.

| Nutritional Component | Primary Hormonal Target | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids | Cortisol & Melatonin | Found in fatty fish, walnuts, and flaxseeds, these fats are crucial for brain health and have been shown to help lower cortisol levels. Some research suggests that low omega-3 levels may be linked to disturbances in melatonin secretion. |

| Magnesium | GABA & Cortisol | This essential mineral, found in leafy greens, nuts, and seeds, plays a critical role in the nervous system. It helps regulate neurotransmitters that promote calmness, such as GABA, and can help to suppress the release of stress hormones from the adrenal glands. |

| Tryptophan-Rich Foods | Serotonin & Melatonin | Tryptophan is an amino acid precursor to serotonin, which is then converted into melatonin in the pineal gland. Consuming foods like turkey, chicken, and oats, particularly with a source of carbohydrates, can enhance tryptophan’s availability to the brain. |

| Complex Carbohydrates | Insulin & Cortisol | Consuming a modest portion of complex carbohydrates like sweet potatoes or quinoa in the evening can be beneficial. The resulting gentle rise in insulin helps to lower cortisol and facilitates the entry of tryptophan into the brain, supporting melatonin production. |

Chronic stress leads to a hyperactive HPA axis, which disrupts the natural cortisol rhythm essential for healthy sleep.

While these lifestyle modifications are profoundly effective, their sufficiency depends on the underlying cause and severity of the hormonal imbalance. For many individuals experiencing sleep issues due to chronic stress or poor lifestyle habits, a dedicated and consistent application of these strategies can be enough to restore healthy sleep patterns.

However, in situations involving significant hormonal shifts, such as the steep decline of estrogen and progesterone during menopause or clinically low testosterone in men, lifestyle changes may become a necessary but incomplete part of the solution. They can improve symptoms and build a foundation of health, but they may not be able to fully compensate for a significant deficit in hormone production. In these cases, lifestyle becomes the essential groundwork that allows for more targeted clinical interventions to be successful.

Academic

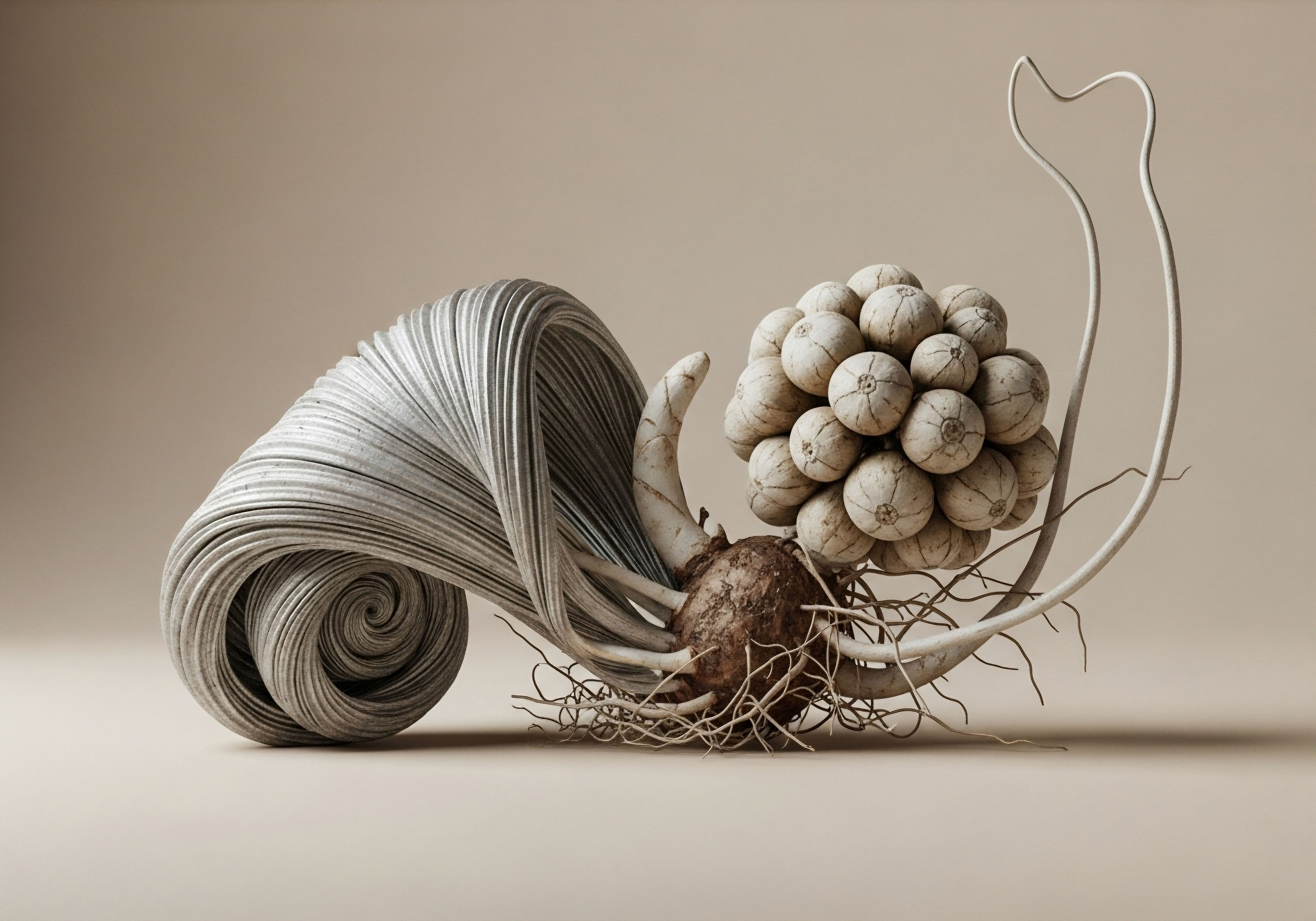

A sophisticated examination of hormonally driven sleep disturbances requires moving beyond individual hormones and into the realm of systems biology. The human body operates through a network of interconnected neuroendocrine axes, primarily the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.

These systems are in constant communication, and a perturbation in one inevitably affects the other. While lifestyle interventions exert considerable influence on these systems, their ability to correct deep-seated dysregulation is finite, particularly when faced with age-related hormonal decline or chronic, pathological activation patterns.

Interplay of the HPA and HPG Axes in Sleep Regulation

The HPA axis, as the central mediator of the stress response, and the HPG axis, which governs reproductive hormones (testosterone in men; estrogen and progesterone in women), are deeply intertwined. Chronic activation of the HPA axis, with its attendant elevation of cortisol, has a suppressive effect on the HPG axis.

Elevated cortisol can inhibit the release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, which in turn reduces the pituitary’s output of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). This cascade results in lower production of testosterone in men and can disrupt the menstrual cycle and estrogen/progesterone production in women.

This interaction has profound implications for sleep. For example, in a perimenopausal woman, the declining output of estrogen and progesterone from the ovaries (a primary HPG axis change) already predisposes her to sleep fragmentation and vasomotor symptoms (night sweats).

If she is also experiencing chronic stress, the resulting HPA axis hyperactivity will further suppress her already dwindling ovarian function while simultaneously elevating nocturnal cortisol. This creates a vicious cycle where HPA dysregulation exacerbates the symptoms of HPG decline, leading to severe, multifactorial sleep disruption that is often resistant to lifestyle interventions alone. While stress management and diet can help modulate the HPA axis, they cannot restart ovarian estrogen production.

Can Lifestyle Overcome the Menopausal Transition?

The menopausal transition provides a clear case study on the limits of lifestyle interventions. The cessation of ovarian follicular activity leads to a dramatic drop in estradiol and progesterone levels. Estradiol is not just a reproductive hormone; it is a potent neurosteroid that influences serotonin and dopamine activity, body temperature regulation, and even the structure of sleep itself.

Progesterone metabolites are positive allosteric modulators of the GABA-A receptor, the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter system in the brain, which is essential for promoting deep, restorative sleep. The loss of these hormones creates a state of neurochemical and physiological disruption.

Lifestyle changes, such as maintaining a cool bedroom, avoiding triggers for hot flashes, and practicing relaxation techniques, can certainly mitigate the symptoms. However, they cannot replace the lost hormones and their critical functions in the central nervous system. Clinical studies have shown that hormone therapy, which restores estrogen and progesterone, can markedly improve sleep disturbances during the menopausal transition, an effect not seen to the same degree with non-hormonal interventions alone.

The interconnectedness of the HPA and HPG axes means that chronic stress can directly suppress reproductive hormones, compounding sleep problems.

A similar principle applies to men with clinically low testosterone (hypogonadism). While sleep deprivation can lower testosterone, and improving sleep can help restore it to a degree, age-related or pathological hypogonadism represents a primary failure of the HPG axis. Men with low testosterone often experience reduced sleep efficiency and less slow-wave sleep.

Lifestyle interventions like resistance training and weight management are crucial for optimizing testosterone production and improving overall health. They are fundamental to any treatment plan. Yet, when testosterone levels are significantly low, these measures may only produce a modest increase, insufficient to resolve symptoms like severe fatigue and poor sleep quality. In such cases, Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) can restore physiological levels, often leading to significant improvements in sleep architecture and quality, working in concert with the foundational lifestyle changes.

The table below outlines the conceptual limits of lifestyle interventions in the context of severe hormonal dysregulation.

| Condition | Role of Lifestyle Changes | Limitation | Potential Clinical Adjunct |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Stress-Induced Insomnia | Primary intervention. Stress reduction, diet, and exercise can recalibrate the HPA axis. | May be insufficient if stress is ongoing and severe, or if a hyper-aroused state has become pathologically ingrained. | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I), targeted peptide therapies (e.g. Sermorelin to improve deep sleep). |

| Perimenopausal/Menopausal Sleep Disruption | Supportive and essential for managing symptoms and overall health. | Cannot restore declining estrogen and progesterone levels to resolve underlying neurochemical deficits. | Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) with estrogen and progesterone. |

| Andropause/Hypogonadism-Related Poor Sleep | Crucial for optimizing natural testosterone production and managing related factors like obesity. | Unlikely to raise clinically low testosterone levels back to a healthy physiological range on its own. | Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT). |

In conclusion, from a systems-biology perspective, lifestyle changes are the most powerful tool available for modulating the function and sensitivity of our neuroendocrine axes. They are the foundation upon which all hormonal health is built. For many, they are sufficient to correct sleep problems stemming from mild to moderate dysregulation.

However, when faced with a primary failure or significant age-related decline within a hormonal system, such as the HPG axis in menopause or andropause, lifestyle changes alone may not be enough to bridge the physiological gap. In these scenarios, their role shifts from a standalone cure to an essential collaborator, creating the stable internal environment required for targeted clinical protocols to effectively and safely restore hormonal balance and, with it, restorative sleep.

References

- Vgenopoulou, I. and G. Chrousos. “HPA Axis and Sleep.” Endotext, edited by K.R. Feingold et al. MDText.com, Inc. 2020.

- Leproult, Rachel, and Eve Van Cauter. “Role of sleep and sleep loss in hormonal release and metabolism.” Endocrine reviews vol. 26,4 (2005) ∞ 513-43.

- Baker, Fiona C. and Ian M. Colrain. “Sleep and reproductive hormones in women.” Sleep Medicine Clinics, vol. 5, no. 3, 2010, pp. 381-92.

- Vgontzas, Alexandros N. et al. “Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with a high risk for hypertension.” Sleep, vol. 32, no. 4, 2009, pp. 491-7.

- Cintron, D. & M. T. Williams. “The role of the HPA axis in sleep research.” Number Analytics, 2025.

- Wittert, G. “The relationship between sleep disorders and testosterone in men.” Asian journal of andrology vol. 16,2 (2014) ∞ 262-5.

- Jehan, Shayan, et al. “The Impact of Sleep and Circadian Disturbance on Hormones and Metabolism.” International Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 2017, 2017, pp. 1 ∞ 16.

- Schier, M. T. et al. “Sleep disturbances across a woman’s lifespan ∞ what is the role of reproductive hormones?.” Journal of sleep research vol. 28,4 (2019) ∞ e12765.

- Hachul, H. et al. “The role of hormones in women’s sleep.” Hormones and Behavior, vol. 66, no. 3, 2014, pp. 557-66.

- Manber, R. and C. S. Armitage. “Sex, steroids, and sleep ∞ a review.” Sleep, vol. 21, no. 5, 1998, pp. 540-55.

Reflection

You have now traveled through the intricate landscape of your body’s internal chemistry, from the foundational rhythms of your sleep hormones to the complex interplay of your central command systems. The knowledge that your lifestyle choices are a direct conversation with your endocrine system is a powerful realization.

This understanding shifts the perspective from one of passive suffering to one of active participation in your own wellness. Your journey to restorative sleep is uniquely yours, written in the language of your own biology.

Where Do You Go from Here?

Consider the information presented here as a map. It shows you the terrain, highlights the key landmarks, and explains the forces of nature at play. It empowers you to make informed decisions about the path you walk each day ∞ the food you eat, the way you move your body, and the priority you give to rest.

For many, diligently following this map will lead them to their destination of better sleep. For others, it may reveal that they are facing a mountain that requires more than just good hiking boots. Recognizing when you might need a skilled guide, in the form of clinical support, is a sign of profound self-awareness. This journey is about reclaiming your vitality, and that begins with honoring the specific needs of your own biological system.

Glossary

hormonally driven sleep problems

your endocrine system

circadian rhythm

sleep disturbances

cortisol levels

estrogen and progesterone

sleep quality

testosterone levels

restorative sleep

poor sleep

lifestyle interventions

endocrine system

hpa axis dysregulation

chronic stress

hpa axis

hormonally driven sleep

lifestyle changes

low testosterone

neuroendocrine axes

reproductive hormones