Fundamentals

You may have arrived here holding a piece of paper, a genetic report that feels both deeply personal and profoundly alien. On it are codes like COMT and CYP1B1, markers that seem to dictate a part of your health narrative you didn’t know was being written.

The feeling that your own biology is working against you is a heavy one. It is a sense of being constrained by an invisible architecture. This exploration begins with a single, powerful premise your genetic blueprint is the beginning of your story, it is the context, not the conclusion. Your daily choices possess the remarkable capacity to influence how these genetic instructions are expressed. You hold the pen, and you can learn to write a new chapter.

Understanding this process starts with understanding estradiol, the primary estrogen in the human body. For women, its role in regulating the menstrual cycle is well-known, yet its influence extends far beyond reproduction. Estradiol is a key regulator of bone density, a modulator of cognitive function and mood, and a protector of cardiovascular health.

In men, appropriate levels of estradiol are just as essential, contributing to libido, erectile function, and bone integrity. It is a systemic signaling molecule, a messenger that carries vital instructions to tissues throughout the body. Its presence is necessary for optimal function. Like any powerful messenger, its messages must be delivered, read, and then responsibly retired. This retirement process is known as metabolism or detoxification.

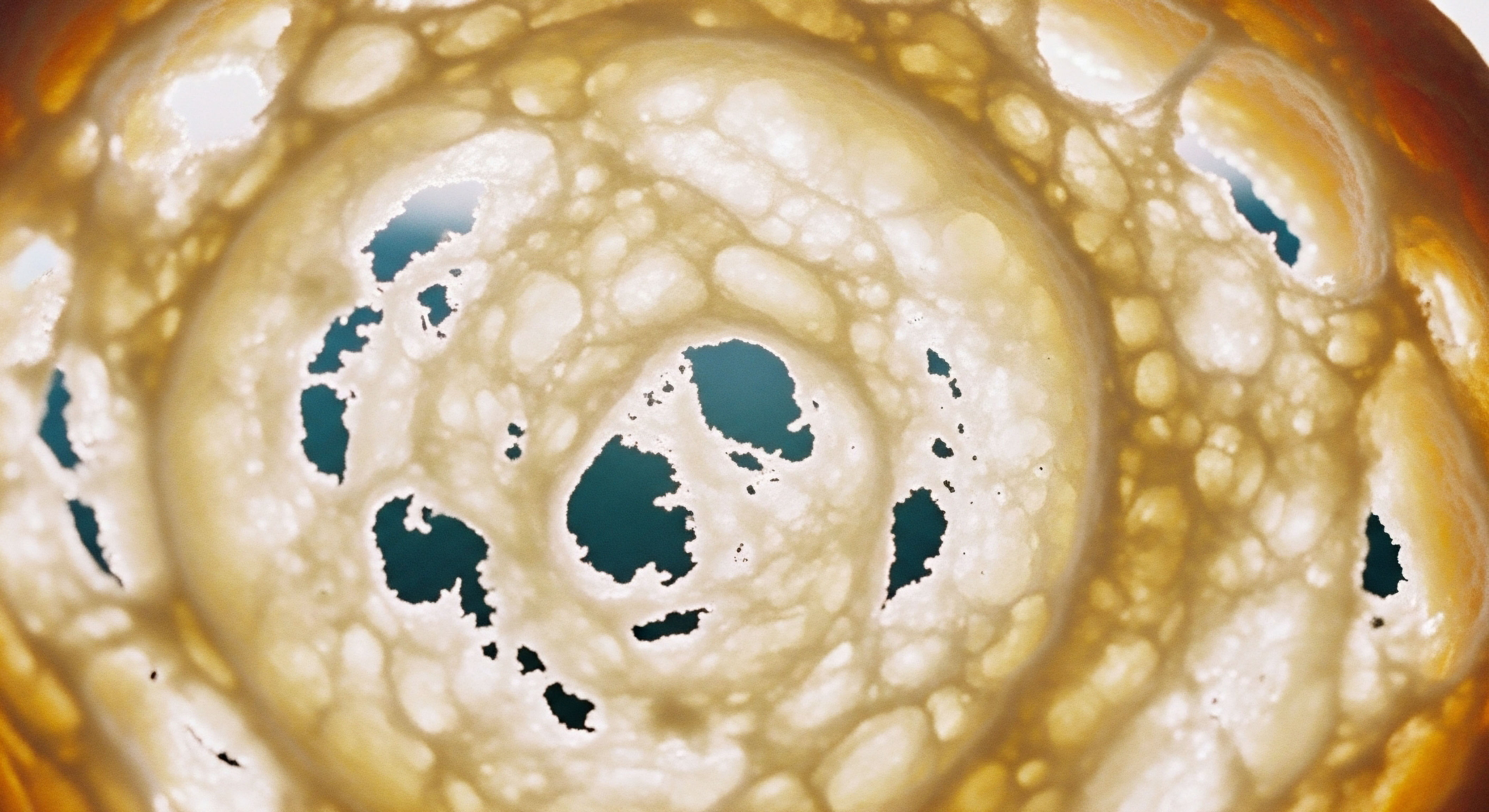

Estradiol metabolism is a carefully orchestrated, two-phase process designed to safely clear the hormone after its work is done.

The Two-Phase Detoxification System

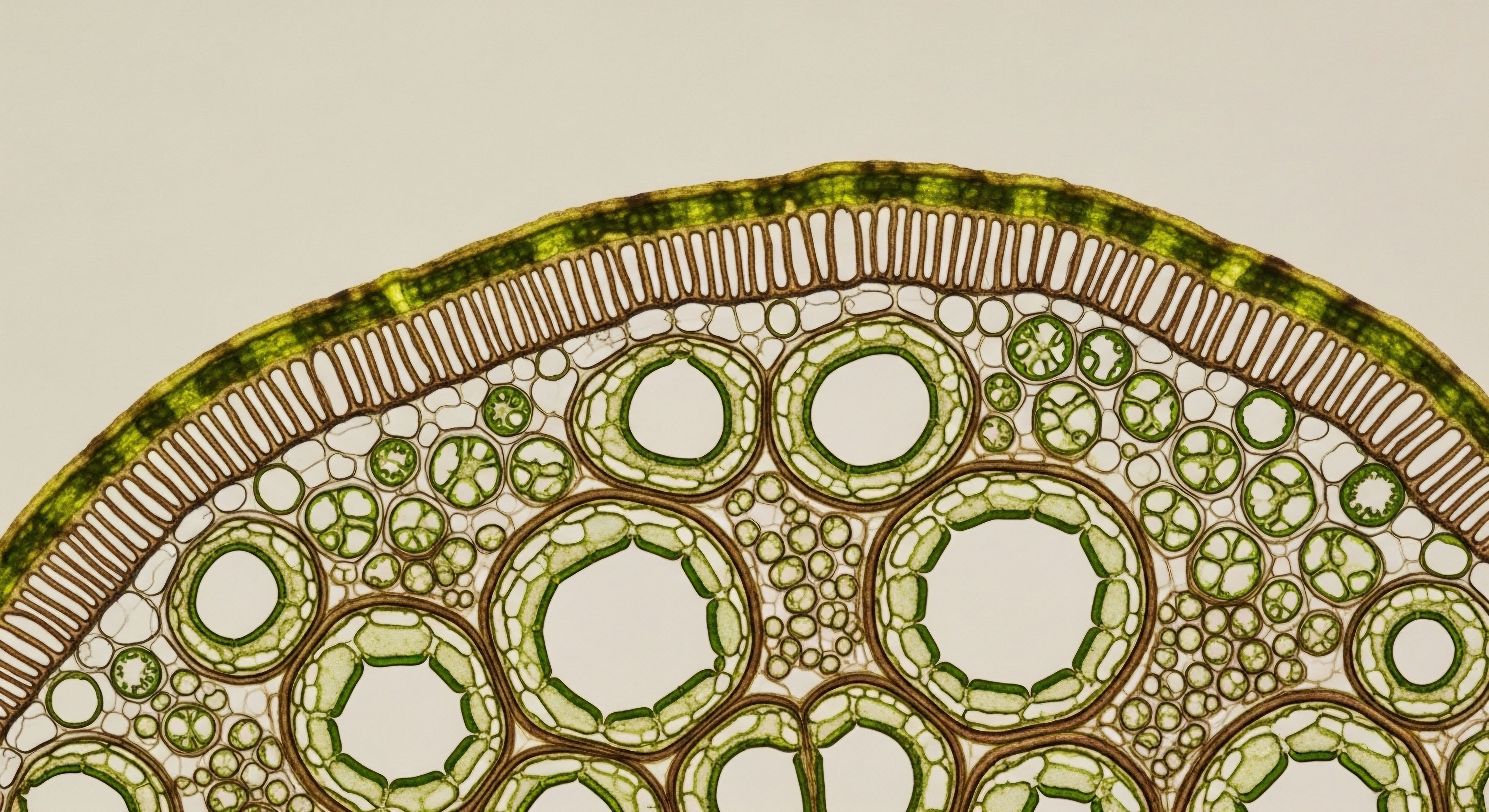

Think of your liver as a sophisticated processing facility with a two-step workflow. When estradiol arrives for decommissioning, it first enters Phase I. Here, a group of enzymes known as the Cytochrome P450 family acts upon it.

This is a functionalization step, where the estradiol molecule is chemically altered, making it more water-soluble and preparing it for the next stage. The primary enzymes involved in this phase are from the CYP1A and CYP1B families. This initial step is complex because it can send estradiol down several different pathways, creating different types of metabolites, or byproducts. Some of these metabolites are benign; others carry potential risks if they are not handled correctly by the next phase.

Following its transformation in Phase I, the estrogen metabolite moves to Phase II. This is the conjugation phase, where the goal is to neutralize the metabolite and package it for final excretion from the body through urine or bile. A key enzyme in this phase is Catechol-O-methyltransferase, or COMT.

This enzyme attaches a methyl group ∞ a small chemical tag ∞ to the metabolite. This process, called methylation, effectively deactivates the metabolite, rendering it harmless and ready for removal. This two-phase system is a fundamental component of your body’s ability to maintain biochemical balance and protect itself from the accumulation of reactive compounds.

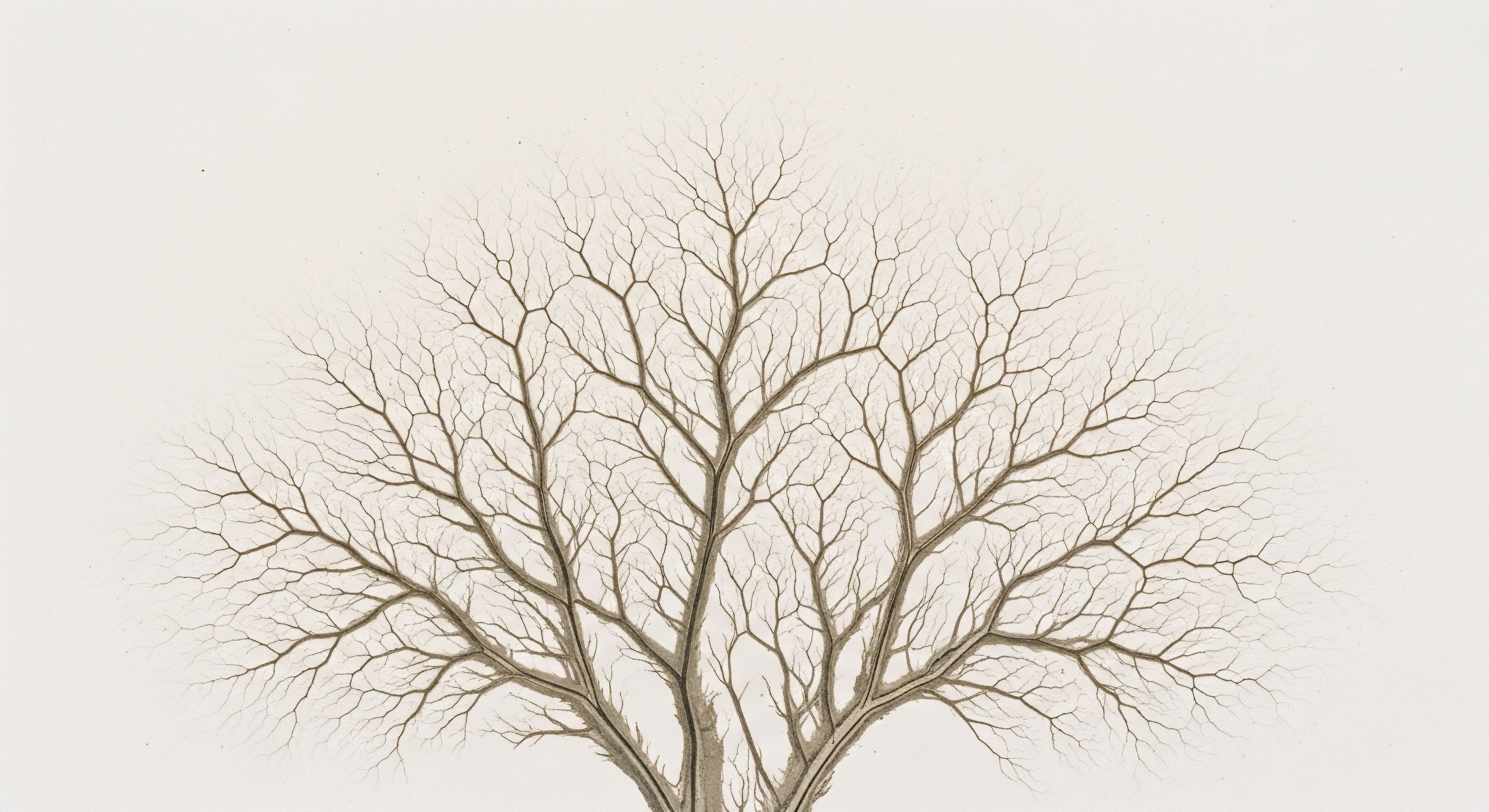

Genetic Variations Define Your Metabolic Signature

Your genetic code provides the instructions for building these metabolic enzymes, like COMT and CYP1B1. Small, common variations in these genes, known as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), can change how efficiently these enzymes work. A variation in your CYP1B1 gene might mean your body preferentially creates more of a specific type of estrogen metabolite.

A variation in your COMT gene, such as the well-studied Val158Met SNP, can result in an enzyme that works at a much slower pace. A slower COMT enzyme means the deactivation process in Phase II is less efficient. Metabolites produced in Phase I may linger for longer periods before they are neutralized.

The specific combination of your genetic variants in these different enzymes creates your unique hormonal metabolic signature. Understanding this signature is the first step toward personalizing your approach to wellness. It allows you to move from a general understanding of health to a specific understanding of your own body’s operational logic.

Intermediate

To truly grasp how lifestyle choices can steer your hormonal health, we must examine the specific pathways of estradiol metabolism with greater precision. The Phase I process does not create a single type of metabolite. Instead, it directs estradiol down three primary routes, each with distinct biological implications. The balance between these pathways is a critical determinant of your long-term cellular health. Your genetics set a baseline for this balance, and your diet and lifestyle can actively shift it.

The Three Metabolic Pathways What Are They?

The hydroxylation of estradiol during Phase I can occur at three different positions on the molecule, creating three families of metabolites. The enzymes responsible, primarily from the Cytochrome P450 family, have preferences for which pathway they activate.

- The 2-Hydroxy (2-OH) Pathway This is broadly considered the most favorable and protective pathway. The resulting metabolite, 2-hydroxyestrone (2-OHE1), has very weak estrogenic activity and is efficiently neutralized and excreted. Enzymes like CYP1A1 and CYP1A2, which are highly active in the liver, are the primary drivers of this route. A higher ratio of 2-OH metabolites compared to others is associated with better health outcomes.

- The 4-Hydroxy (4-OH) Pathway This pathway presents a greater potential for cellular risk. The metabolite 4-hydroxyestrone (4-OHE1) is chemically reactive. If it is not swiftly neutralized by Phase II enzymes like COMT, it can be oxidized into compounds called quinones. These quinones can bind to DNA, creating adducts that may lead to mutations. The enzyme CYP1B1, found in tissues like the breast, prostate, and uterus, is the main catalyst for this pathway. Unfavorable variations in the CYP1B1 gene can increase its activity, producing more 4-OH metabolites.

- The 16-Hydroxy (16-OH) Pathway This pathway produces 16-alpha-hydroxyestrone (16-OHE1), a metabolite that retains significant estrogenic activity. It can bind to estrogen receptors and continue to exert strong hormonal effects on tissues. High levels of 16-OHE1 are associated with conditions of estrogen excess.

How Do Genes Influence These Metabolic Roads?

Your genetic predispositions act as traffic directors for these pathways. A “slow” COMT variant (like the Met/Met genotype at the Val158Met position) means the Phase II detoxification of catechol estrogens (both 2-OHE1 and 4-OHE1) is impaired. When this is combined with a highly active CYP1B1 enzyme that produces a steady stream of 4-OH metabolites, a biochemical bottleneck can occur.

The reactive 4-OH metabolites may accumulate faster than the slow COMT can clear them, increasing the potential for oxidative stress and DNA damage. This genetic combination underscores a specific biological vulnerability. It is this specific vulnerability that targeted diet and lifestyle interventions can support.

Strategic nutritional choices provide the raw materials your body needs to optimize its inherent metabolic pathways.

Nutritional Interventions to Support Healthy Metabolism

You can consciously consume foods and nutrients that provide the cofactors for key enzymes or that help steer metabolism toward the more favorable 2-OH pathway. This is the essence of nutrigenomics using nutrition to modulate gene expression.

Table of Nutritional Support for Estradiol Metabolism

| Nutrient/Compound | Mechanism of Action | Dietary Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Indole-3-Carbinol (I3C) & Diindolylmethane (DIM) | Promotes the 2-OH pathway by inducing the CYP1A1 enzyme. It helps shift the metabolic traffic away from the 4-OH route. | Cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, Brussels sprouts). |

| B Vitamins (Folate, B6, B12) | Serve as essential cofactors for the methylation cycle, which produces the SAMe molecule required by the COMT enzyme to function. | Leafy green vegetables, legumes, seeds, fish, poultry. |

| Magnesium | Acts as a critical cofactor for the COMT enzyme itself. Proper magnesium levels are required for the methylation reaction to occur efficiently. | Nuts, seeds, whole grains, dark chocolate, leafy greens. |

| Dietary Fiber | Binds to metabolized estrogens in the digestive tract, preventing their reabsorption and ensuring their final excretion from the body. | Whole grains, legumes, fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds. |

| Antioxidants (e.g. EGCG, Resveratrol, Sulforaphane) | Help neutralize the reactive quinones that can be formed from 4-OH metabolites, protecting DNA from damage. | Green tea (EGCG), grapes (resveratrol), broccoli sprouts (sulforaphane). |

| Rosemary & Turmeric | These herbs contain compounds that support both Phase I and Phase II detoxification, enhancing the overall capacity of the liver to process hormones. | Herbs and spices used in cooking. |

The Impact of Broader Lifestyle Choices

Your daily habits also exert a powerful influence on these biochemical systems. Managing these factors is a direct way to reduce the burden on your detoxification pathways.

Table of Lifestyle Factors and Hormonal Metabolism

| Lifestyle Factor | Impact on Estradiol Metabolism | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Consumption | Burdens the liver, consuming enzymes and nutrients (like B vitamins) that are also needed for hormone detoxification. It can impair methylation. | Limit or avoid alcohol intake to free up metabolic resources for hormone processing. |

| Excess Adipose Tissue | Fat cells contain the aromatase enzyme, which converts androgens into estrogen, increasing the total estrogen load that the body must metabolize. | Maintain a healthy body composition through regular physical activity and a balanced diet. |

| Chronic Stress | The stress response pathway can deplete the body’s pool of methyl donors, directly competing with the COMT enzyme for the resources needed for detoxification. | Incorporate stress management techniques like mindfulness, meditation, or deep breathing exercises. |

| Xenoestrogen Exposure | Chemicals in plastics (BPA), personal care products (phthalates), and pesticides can mimic estrogen, adding to the body’s total estrogenic burden. | Choose glass over plastic, use natural personal care products, and opt for organic produce when possible. |

By understanding these connections, you can see that having an “unfavorable” gene is not a sentence. It is an invitation. It is a call to provide your body with a higher level of support in the specific areas where it is needed most. A slow COMT requires robust support for methylation. A highly active CYP1B1 requires a dedicated strategy to promote the 2-OH pathway and supply antioxidants. Your daily actions become a form of biological conversation with your genes.

Academic

An academic exploration of mitigating genetic risks in estradiol metabolism requires a systems-biology perspective. We must synthesize information from endocrinology, genetics, and gastroenterology to appreciate the interconnectedness of the systems involved. The dialogue between your genes, your diet, and your gut microbiome collectively dictates the metabolic fate of estradiol.

A particularly insightful angle is the examination of the estrobolome ∞ the aggregate of enteric bacterial genes capable of metabolizing estrogens ∞ and its interaction with host genetics, specifically COMT and CYP1B1 polymorphisms.

The Gut Microbiome the Estrobolome and Enterohepatic Circulation

After estradiol metabolites are conjugated in the liver (Phase II), a significant portion is excreted into the gut via bile for elimination. Here, they encounter the vast microbial community of the gut. Certain species of gut bacteria produce an enzyme called β-glucuronidase.

This enzyme can effectively reverse the Phase II conjugation, cleaving the glucuronic acid molecule from the estrogen metabolite. This de-conjugation process “reactivates” the estrogen, allowing it to be reabsorbed from the gut back into the bloodstream. This process is known as enterohepatic circulation.

A dysbiotic gut microbiome, characterized by an overgrowth of β-glucuronidase-producing bacteria, can lead to a significant increase in the reabsorption of estrogens. This effectively increases the total systemic estrogen load, placing a greater burden on the liver’s metabolic pathways. For an individual with a slow COMT variant, this recirculation is particularly problematic.

The already-strained detoxification system is presented with the same estrogens to metabolize again, compounding the potential for the accumulation of reactive intermediates like the 4-OH quinones. The health of the gut is therefore a primary variable in managing genetic estrogen metabolism risks.

The composition of the gut microbiome directly modulates the body’s total estrogen burden, acting as a key regulator of hormonal balance.

Dietary fiber and plant-based diets directly influence the estrobolome. Soluble and insoluble fibers are fermented by beneficial bacteria, producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which lower the gut pH. This lower pH inhibits the activity of β-glucuronidase.

Furthermore, a diet rich in diverse plant fibers promotes a healthier, more diverse microbiome, reducing the populations of the bacteria that produce this enzyme. Calcium D-glucarate, a supplemental nutrient, acts as a direct inhibitor of β-glucuronidase, further supporting the permanent excretion of estrogen metabolites.

Molecular Mechanisms Nutrigenomics in Action

The influence of diet extends to the level of gene transcription. Compounds from cruciferous vegetables provide a clear example of this nutrigenomic control.

- Activation of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) Indole-3-carbinol (I3C), a compound in broccoli and its relatives, is converted to diindolylmethane (DIM) in the stomach’s acidic environment. DIM is a potent ligand for the Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR), a transcription factor present in liver cells.

- Induction of CYP1A1 Expression When DIM binds to the AhR, the complex translocates to the cell nucleus. There, it binds to specific DNA sequences known as xenobiotic response elements (XREs) in the promoter region of certain genes, including CYP1A1.

- Shifting the Metabolic Ratio This binding event initiates the transcription of the CYP1A1 gene, leading to the synthesis of more CYP1A1 enzyme. As the CYP1A1 enzyme preferentially catalyzes the 2-OH pathway, this increased expression effectively shifts the flow of estradiol metabolism toward the production of the protective 2-OHE1 metabolite, and away from the potentially harmful 4-OH pathway catalyzed by CYP1B1.

This is a direct, mechanistic pathway through which a dietary choice can modify the expression of a key metabolic gene to produce a more favorable health outcome, actively compensating for a genetic predisposition that might favor the 4-OH pathway.

The Centrality of the Methylation Cycle

The function of the COMT enzyme cannot be viewed in isolation. It is entirely dependent on a larger biochemical process known as the methylation cycle. This cycle’s primary output is the molecule S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe), the universal methyl donor for countless reactions in the body, including the COMT-mediated neutralization of catechol estrogens.

The production of SAMe is, in turn, dependent on a steady supply of cofactors, most notably activated forms of folate (5-MTHF), vitamin B12 (methylcobalamin), and vitamin B6 (P-5-P).

A genetic polymorphism in the MTHFR gene (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase) can impair the ability to produce the active 5-MTHF form of folate. An individual with both a slow COMT variant and a compromising MTHFR variant faces a compounded challenge. Their ability to produce the methyl donor (SAMe) is reduced, and the enzyme that needs that donor (COMT) is already inefficient.

This creates a significant bottleneck in Phase II detoxification. For such individuals, dietary and supplemental intervention is not merely supportive; it is a biochemical necessity. Providing the body with pre-activated B vitamins (like 5-MTHF instead of folic acid) and ensuring adequate magnesium and protein intake (for methionine) provides the raw materials to overcome these genetic hurdles and maintain the velocity of the methylation cycle.

This ensures the COMT enzyme is never starved of the SAMe it requires to do its job, mitigating the risk posed by its slower operating speed.

These interconnected systems demonstrate that genetic predispositions related to estradiol metabolism do not exist in a vacuum. They are nodes within a complex network that is highly responsive to external inputs. The state of the gut microbiome, the transcriptional influence of dietary compounds, and the nutritional support for foundational biochemical cycles like methylation are all powerful levers that can be used to modify the expression of genetic risk, promoting a safer and more efficient metabolic profile.

References

- Zhu, B. T. & Conney, A. H. (1998). Functional role of estrogen metabolism in target cells ∞ review and perspectives. Carcinogenesis, 19(1), 1-27.

- Lord, R. S. & Bong, Y. L. (2012). Laboratory evaluations for integrative and functional medicine. Metametrix Institute.

- Jernström, H. & Klug, T. L. (2002). Estrogen metabolism and breast cancer ∞ a review. Breast Cancer Research, 4(2), 1-9.

- Bradlow, H. L. Telang, N. T. Sepkovic, D. W. & Osborne, M. P. (1996). 2-hydroxyestrone ∞ the ‘good’ estrogen. Journal of Endocrinology, 150(Supplement), S259-S265.

- Cavalieri, E. Stack, D. Devanesan, P. Todorovic, R. Dwivedy, I. Higginbotham, S. Johansson, S. L. Patil, K. D. Gross, M. L. Gooden, J. K. & Ramanathan, R. (1997). Molecular origin of cancer ∞ catechol estrogen-3,4-quinones as endogenous tumor initiators. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 94(20), 10937-10942.

- Lampe, J. W. (2009). Interindividual differences in response to dietary factors ∞ influence of genetics and the microbiome. Breast Cancer Research, 11(Suppl 3), S9.

- Haggerty, T. D. et al. (2020). Genetic Biomarkers of Metabolic Detoxification for Personalized Lifestyle Medicine. Metabolites, 10(4), 143.

- Ervin, S. M. et al. (2018). Associations between the CYP17, CYPIB1, COMT and SHBG polymorphisms and serum sex hormones in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors. Journal of internal medicine, 284(3), 266-278.

- Pluchino, N. et al. (2020). The role of the estrobolome in female health and disease. Climacteric, 23(sup1), 22-29.

- Worboys, M. & Dupré, J. (2005). The literature of the life sciences. The Cambridge history of science, 6, 457-482.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here is a map, not a destination. You have seen the pathways, the intersections, and the biological traffic signals that influence your hormonal health. You now understand that your genetic code is a terrain, and your lifestyle choices are the vehicle you use to navigate it.

Some terrains are smoother, others more challenging, but the power to steer, to choose a path of less resistance, remains with you. What part of your daily rhythm could become a more conscious act of biological support? What is the first small, sustainable change you can make to begin speaking a new language of wellness to your body? The journey to personalized health begins with this type of internal query, transforming abstract knowledge into a personal, proactive potential.

Glossary

cyp1b1 gene

comt enzyme

comt gene

estradiol metabolism

2-hydroxyestrone

4-hydroxyestrone

phase ii detoxification

nutrigenomics

2-oh pathway

gut microbiome

the estrobolome

enterohepatic circulation

metabolic pathways

slow comt variant

estrobolome

cruciferous vegetables