Fundamentals

The question of whether lifestyle adjustments can reduce the need for hormonal intervention is a profound one. It speaks to a deep desire to understand the body’s internal language and to participate in its processes. Your body is a responsive, dynamic biological environment.

Every system within it, from the cellular to the systemic, is in constant communication. The endocrine network, which produces and regulates hormones, functions as this system’s primary messaging service. These chemical messengers travel through your bloodstream, delivering precise instructions that govern your energy, your mood, your cognitive function, and your reproductive capacity.

When you experience symptoms like fatigue, mood shifts, or changes in your cycle, it is a signal that this internal communication network is adapting. These are not failures of your body; they are its logical responses to a changing internal landscape. Viewing your health through this lens transforms the conversation. It becomes a process of learning to provide your body with the foundational inputs it requires to maintain its equilibrium.

Lifestyle adjustments represent the most powerful set of tools you have to influence this internal environment. Nutrition, movement, stress modulation, and sleep are not merely activities. They are biochemical and physiological inputs that directly inform the behavior of your endocrine system. The food you consume provides the raw materials for hormone synthesis.

The quality of your sleep dictates the rhythmic rise and fall of critical hormones like cortisol. Physical activity influences insulin sensitivity and the production of endorphins, which in turn affects your stress response. Each choice is a piece of information you provide to your biological systems.

Understanding this relationship is the first step toward reclaiming a sense of agency over your health. It allows you to move from a position of reacting to symptoms to proactively supporting the very systems that govern your vitality. The journey into hormonal health begins with this recognition that you are an active participant in the intricate dance of your own physiology.

The Language of Hormones

To understand how to support your endocrine system, you must first learn its language. The primary female sex hormones, estrogen and progesterone, are central characters in this biological narrative. Estrogen, in its most potent form as estradiol, is a hormone of growth and proliferation.

It builds the uterine lining, supports bone density, maintains collagen in the skin, and has significant effects on neurotransmitters in the brain, influencing mood and cognitive function. Progesterone is its balancing partner. It is a calming, anti-anxiety hormone that secures the uterine lining after ovulation, promotes sleep, and helps to regulate the fluid balance in the body. The cyclical interplay between these two hormones defines the menstrual cycle and contributes to a woman’s overall sense of well-being.

During the perimenopausal transition, the regular, predictable rhythm of this hormonal conversation begins to change. Ovarian production of estrogen and progesterone becomes more erratic. This fluctuation is the direct cause of many of the symptoms women experience. Hot flashes can be linked to the effect of declining estrogen on the hypothalamus, the brain’s thermostat.

Sleep disturbances may arise from the loss of calming progesterone. Mood changes are often connected to the shifting influence of these hormones on brain chemistry. These symptoms are tangible, physical manifestations of a deep systemic recalibration. They are valuable data points, providing clear feedback about the state of your internal hormonal environment.

Foundational Pillars of Support

The capacity of lifestyle adjustments to mitigate these symptoms lies in their ability to support the body’s overall resilience and efficiency. When the primary hormonal pathways are in flux, the health of your other biological systems becomes even more significant. There are three core areas where lifestyle provides this foundational support.

- Nutrient-Dense Nutrition The body requires specific vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients to produce hormones and their metabolites. A diet rich in whole foods provides these essential building blocks. Cruciferous vegetables, for instance, contain compounds that support healthy estrogen detoxification pathways in the liver. Healthy fats are the direct precursors for steroid hormones, including estrogen and progesterone. Fiber from plant foods is essential for gut health, which plays a surprisingly direct role in regulating circulating estrogen levels.

- Consistent Physical Activity Regular movement has profound effects on hormonal balance. It improves insulin sensitivity, which is critical because insulin resistance can place additional stress on the endocrine system and contribute to hormonal imbalances. Weight-bearing exercise helps to counteract the decline in bone density that can accompany lower estrogen levels. Exercise is also a powerful modulator of the stress response, helping to regulate cortisol and boost mood-lifting endorphins.

- Stress And Sleep Hygiene The stress response system, governed by the adrenal glands, is intricately linked with the reproductive hormone system. Chronic stress leads to chronically elevated levels of the hormone cortisol. High cortisol can disrupt ovulation and suppress the production of progesterone, further exacerbating the imbalances of perimenopause. Prioritizing restorative sleep and implementing stress-reduction practices are direct interventions that help to calm this system, allowing the body to allocate its resources more effectively and maintain a healthier hormonal equilibrium.

These pillars work together, creating a synergistic effect that enhances the body’s ability to navigate the hormonal shifts of perimenopause and menopause. They do not stop the transition, but they provide the biological support necessary to make the process smoother and to reduce the severity of its associated symptoms.

Intermediate

To appreciate how lifestyle adjustments can influence hormonal health, we must examine the body’s intricate regulatory architecture. The primary control system for female reproductive hormones is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This is a sophisticated feedback loop that connects the brain to the ovaries.

The hypothalamus, a region in the brain, releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH). This signals the pituitary gland to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These hormones then travel to the ovaries, stimulating follicle development and the production of estrogen and progesterone.

The levels of these ovarian hormones then feed back to the brain, modulating the release of GnRH, LH, and FSH in a continuous, dynamic cycle. During perimenopause, this finely tuned communication system begins to lose its precision as the ovaries become less responsive to pituitary signals, leading to the characteristic fluctuations in hormone levels.

A woman’s hormonal state is a direct reflection of the communication quality between her brain and her endocrine glands.

Running in parallel to the HPG axis is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s central stress response system. When the brain perceives a stressor, the hypothalamus releases Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH), which signals the pituitary to release Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH). ACTH then stimulates the adrenal glands to produce cortisol.

Cortisol is essential for survival; it mobilizes energy, modulates inflammation, and increases alertness. These two axes, the HPG and the HPA, are deeply interconnected. They compete for shared biochemical resources and influence one another’s signaling. Chronic activation of the HPA axis can directly suppress the function of the HPG axis.

High levels of cortisol can inhibit the release of GnRH from the hypothalamus, effectively downregulating the entire reproductive cascade. This is a key mechanism through which chronic stress can disrupt menstrual cycles and worsen the symptoms of hormonal imbalance. Lifestyle interventions are powerful because they directly modulate the activity of the HPA axis, thereby supporting the function of the HPG axis.

Nutritional Biochemistry as a Hormonal Lever

Nutrition provides the specific chemical precursors and cofactors required for hormone production, metabolism, and detoxification. Thinking of food as biochemical information allows for a more targeted approach to supporting hormonal health.

Phytoestrogens and Their Role

Phytoestrogens are plant-derived compounds that have a chemical structure similar to human estrogen. This similarity allows them to bind to estrogen receptors in the body. There are two main types of estrogen receptors ∞ alpha receptors and beta receptors. Phytoestrogens tend to have a higher affinity for the beta receptors.

This binding action produces a weak estrogenic effect, which can be beneficial during perimenopause. When the body’s own estrogen levels are low, phytoestrogens can provide a mild estrogenic signal, potentially helping to alleviate symptoms like hot flashes. Conversely, when estrogen levels are high, they can occupy estrogen receptors, blocking the binding of more potent endogenous estrogen. Good sources include flaxseeds, soy products like tofu and tempeh, and chickpeas.

Supporting Estrogen Metabolism

Once estrogen has performed its function, it must be metabolized and cleared from the body, primarily by the liver. This process occurs in two phases. Phase I detoxification involves a group of enzymes known as cytochrome P450. Phase II involves conjugation, where molecules are attached to the estrogen metabolites to make them water-soluble and ready for excretion. Certain nutrients are critical for these pathways.

- Cruciferous Vegetables Foods like broccoli, cauliflower, and kale contain a compound called indole-3-carbinol, which supports the production of less potent and potentially protective estrogen metabolites during Phase I detoxification.

- B Vitamins Vitamins B6, B12, and folate are essential for methylation, a key conjugation pathway in Phase II. Leafy green vegetables, legumes, and lean meats are rich in these vitamins.

- Fiber and the Estrobolome After conjugation in the liver, estrogen metabolites are excreted into the gut via bile. The gut microbiome, often called the “estrobolome,” produces an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. This enzyme can deconjugate the estrogen, allowing it to be reabsorbed back into circulation. A high-fiber diet promotes a healthy and diverse gut microbiome, which helps to maintain a balanced level of beta-glucuronidase activity, ensuring proper estrogen excretion and preventing its excessive recirculation.

Exercise as an Endocrine Modulator

Physical activity is a potent modulator of the endocrine system. The type, intensity, and duration of exercise determine its specific hormonal effects. A balanced exercise regimen can improve metabolic health, support bone density, and regulate the stress response.

The table below outlines the distinct hormonal impacts of different exercise modalities, offering a framework for creating a balanced weekly routine.

| Exercise Modality | Primary Hormonal Impact | Physiological Benefit |

|---|---|---|

|

Weight-Bearing Strength Training |

Increases growth hormone and testosterone signaling; improves insulin sensitivity. |

Builds and maintains muscle mass, which improves metabolic rate. Directly stimulates bone formation, counteracting osteopenia and osteoporosis risk. |

|

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) |

Acutely increases cortisol and catecholamines, followed by an improvement in receptor sensitivity. |

Improves cardiovascular fitness and metabolic flexibility. The acute stress response can improve the body’s overall stress resilience when properly balanced with recovery. |

|

Moderate-Intensity Cardio (e.g. Brisk Walking, Cycling) |

Lowers resting cortisol levels over time; increases endorphin production. |

Enhances cardiovascular health, improves mood, and helps to manage weight without significantly taxing the HPA axis. |

|

Mind-Body Movement (e.g. Yoga, Tai Chi) |

Downregulates the HPA axis; increases GABA, a calming neurotransmitter. |

Reduces perceived stress and anxiety. Improves flexibility and balance. Studies show yoga can be beneficial for menopausal symptoms. |

Can Lifestyle Truly Replace Hormonal Intervention?

Lifestyle adjustments are foundational for health and can significantly mitigate many symptoms of perimenopause and menopause. For some women, these changes alone may be sufficient to navigate the transition comfortably. However, for others experiencing severe symptoms, such as debilitating hot flashes, significant bone density loss, or profound mood disturbances, lifestyle changes may not be enough to restore quality of life.

In these cases, Menopausal Hormone Therapy (MHT) is recognized as the most effective treatment available. The goal is to see lifestyle and hormonal interventions as complementary strategies. A well-formulated lifestyle protocol can enhance the effectiveness of MHT, potentially allowing for the use of lower doses.

It also addresses aspects of health that MHT does not, such as metabolic function and stress resilience. The decision to use hormonal intervention is a personal one, made in consultation with a knowledgeable healthcare provider, based on an individual’s symptoms, health history, and goals.

Academic

A systems-biology perspective reveals that the clinical presentation of perimenopause is the emergent property of complex, bidirectional interactions between the endocrine, nervous, and gastrointestinal systems. The decline in ovarian estradiol and progesterone production is the initiating event, but the subsequent cascade of symptoms is profoundly influenced by the functional status of two critical subsystems ∞ the gut microbiome, specifically the estrobolome, and the sleep-wake regulation system, which is governed by the interplay of the circadian clock and the HPA axis.

Lifestyle interventions derive their therapeutic power from their ability to directly modulate the function of these subsystems, thereby altering the feedback loops that can otherwise amplify hormonal symptomatology.

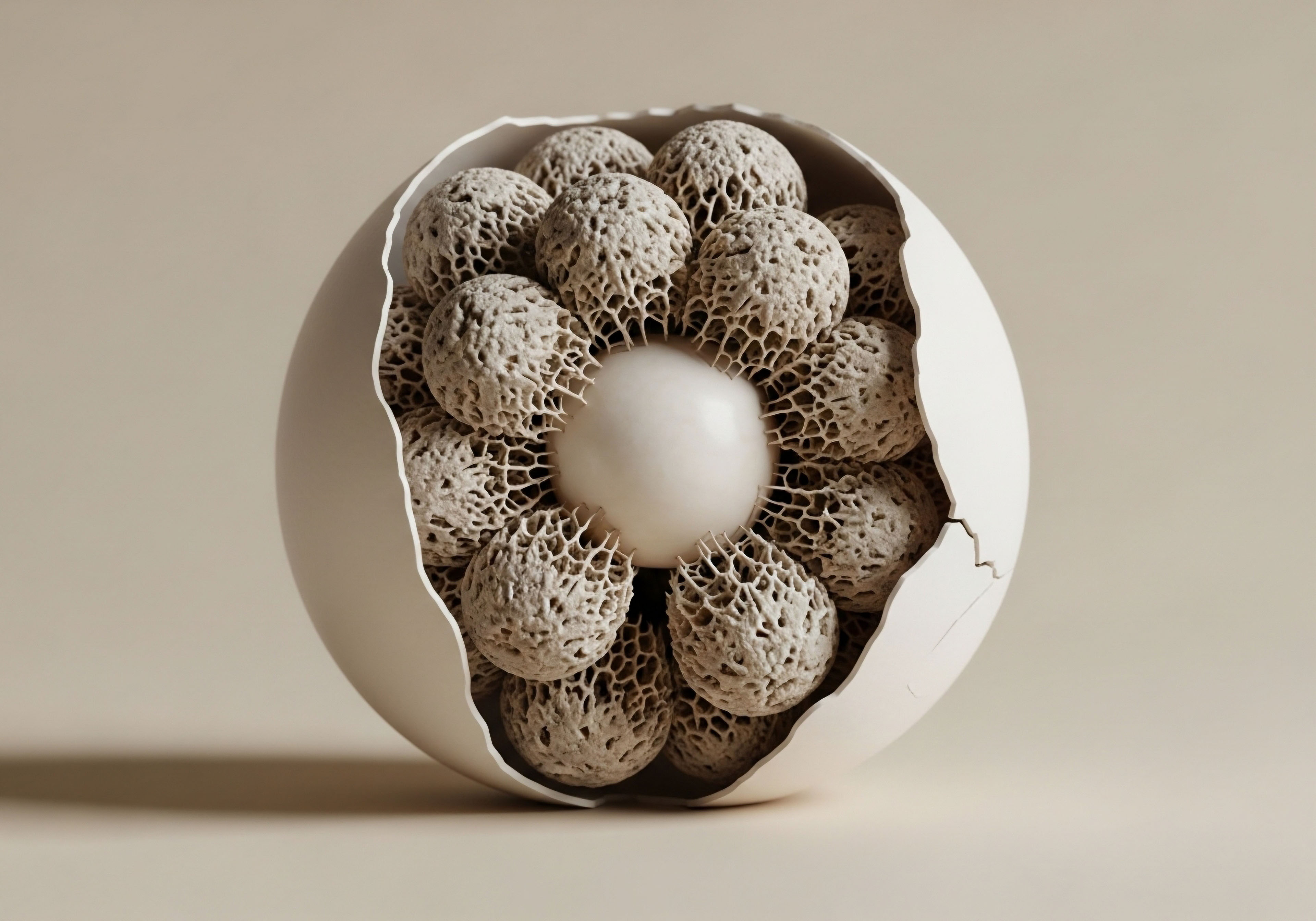

The Gut-Estrogen Axis a Deep Dive into the Estrobolome

The gut microbiome functions as an endocrine organ in its own right, with a specialized capacity to metabolize and regulate steroid hormones, including estrogens. This functional collection of microbes and their genes is termed the “estrobolome.” Its primary mechanism of action involves the enterohepatic circulation of estrogens.

Estrogens produced in the ovaries are transported to the liver, where they undergo glucuronidation, a Phase II detoxification process that attaches a glucuronic acid molecule. This conjugation renders the estrogen inactive and water-soluble, preparing it for excretion into the gut via bile.

Within the intestinal lumen, certain bacteria in the estrobolome produce the enzyme β-glucuronidase. This enzyme cleaves the glucuronic acid from the estrogen conjugate, reactivating it. The now free, unconjugated estrogen can be reabsorbed through the intestinal wall back into systemic circulation.

The level of β-glucuronidase activity in the gut is a critical determinant of the body’s circulating estrogen load. A healthy, diverse microbiome maintains a homeostatic balance of this enzyme. However, gut dysbiosis, characterized by a loss of microbial diversity and an overgrowth of certain pathogenic species, can lead to either elevated or depressed β-glucuronidase activity.

Elevated activity can increase estrogen reabsorption, contributing to conditions of estrogen excess. Depressed activity can lead to increased estrogen excretion and lower circulating levels, potentially exacerbating the estrogen deficiency of menopause.

The composition of a woman’s gut microbiome directly influences her circulating estrogen levels, acting as a key regulator of hormonal balance.

Research has begun to identify specific microbial taxa associated with estrogen levels. Studies have shown that a higher abundance of the phylum Bacteroidetes and a lower Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio are correlated with higher estrogen levels in healthy women. Conversely, a decrease in microbial diversity, as is often seen in postmenopausal women, is associated with lower circulating estrogen.

This creates a challenging feedback loop ∞ declining estrogen during menopause can reduce gut microbial diversity, which in turn further impairs the body’s ability to regulate the remaining estrogen. Lifestyle factors, particularly diet, are the most potent modulators of the gut microbiome.

The table below details specific dietary inputs and their mechanistic effects on the estrobolome, providing a clinical rationale for nutritional protocols.

| Dietary Component | Mechanism of Action | Impact on Estrobolome |

|---|---|---|

|

Dietary Fiber (Inulin, Pectin, Oligosaccharides) |

Serves as a prebiotic substrate for beneficial bacteria, promoting their growth and the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate. |

Increases microbial diversity. Butyrate nourishes colonocytes, strengthens the gut barrier, and helps to modulate local inflammation, creating a healthier environment for a balanced estrobolome. |

|

Polyphenols (from berries, green tea, dark chocolate) |

Exert selective antimicrobial effects against pathogenic bacteria while promoting the growth of beneficial species like Akkermansia muciniphila. |

Shifts the microbial composition toward a more favorable profile, potentially reducing inflammation and supporting the integrity of the gut lining. |

|

Fermented Foods (Yogurt, Kefir, Kimchi) |

Introduce live probiotic bacteria, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species, directly into the gut ecosystem. |

Can help to restore microbial diversity and compete with pathogenic bacteria for resources, supporting a more balanced gut environment. Reduced levels of these bacteria are noted in perimenopause. |

|

Phytoestrogens (Lignans from flax, Isoflavones from soy) |

Are metabolized by the gut microbiota into their active forms (e.g. lignans are converted to enterolactone and enterodiol). |

The presence of specific bacteria is required for this conversion, highlighting a symbiotic relationship. These active metabolites then exert their weak estrogenic effects. |

Sleep Architecture HPA Axis and Hormonal Recalibration

The relationship between sleep and the endocrine system is bidirectional and exquisitely sensitive. Sleep architecture, the cyclical pattern of sleep stages, is not merely a passive state of rest; it is an active process of neurological and physiological restoration during which the endocrine system undergoes critical regulation.

The HPA axis and the secretion of cortisol are tightly linked to the sleep-wake cycle. Normally, cortisol levels reach their nadir in the early hours of sleep, remain low during the period of slow-wave sleep (SWS), and then begin to rise in the early morning, reaching a peak just after awakening (the Cortisol Awakening Response, or CAR). This rhythm is essential for healthy metabolic function and daytime alertness.

How Does Hormonal Change Disrupt Sleep?

The menopausal transition disrupts this system through several mechanisms. The decline in estrogen can directly affect thermoregulation, leading to nocturnal hot flashes (vasomotor symptoms) that cause arousals and fragment sleep. The loss of progesterone, which has sedative and anxiolytic properties through its metabolite allopregnanolone acting on GABA receptors, removes a key calming influence on the brain, making it more difficult to initiate and maintain sleep.

This sleep fragmentation, even without a reduction in total sleep time, is a significant physiological stressor. It disrupts the normal overnight suppression of the HPA axis, leading to elevated nocturnal cortisol levels. This creates a vicious cycle ∞ hormonal changes disrupt sleep, and the resulting sleep disruption further dysregulates the HPA axis, which can then worsen hormonal symptoms and mood disturbances.

What Is the Impact of Sleep Apnea?

Furthermore, the incidence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) increases dramatically in women after menopause. Estrogen and progesterone play a role in maintaining the tone of the upper airway muscles. As these hormones decline, the airway is more susceptible to collapse during sleep.

OSA leads to intermittent hypoxia (low oxygen levels), which is a powerful activator of the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system. Each apneic event triggers a surge of cortisol and catecholamines, leading to severe sleep fragmentation and chronically elevated stress hormone levels.

Many women who develop OSA in perimenopause do not present with the classic symptom of loud snoring; they may experience morning headaches, daytime fatigue, and unrefreshing sleep, which are often mistakenly attributed solely to the hormonal transition itself.

Can Lifestyle Interventions Restore Sleep?

Lifestyle interventions aimed at improving sleep hygiene and managing stress can help to restore a more normal HPA axis rhythm. Techniques that promote a shift toward the parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) nervous system before bed are particularly effective.

- Consistent Sleep Schedule Maintaining a regular bedtime and wake time, even on weekends, helps to anchor the body’s circadian rhythm, promoting a more predictable cortisol pattern.

- Management of Light Exposure Exposure to bright light in the morning helps to stimulate a robust CAR and entrain the circadian clock. Conversely, minimizing exposure to blue light from screens in the evening allows for the natural production of melatonin, the hormone that signals sleep onset.

- Stress Reduction Practices Activities like meditation, deep breathing exercises, and gentle yoga can lower evening cortisol levels, making it easier to fall asleep. These practices help to downregulate the sympathetic nervous system and quiet the mind.

By focusing on the restoration of gut health and the optimization of sleep architecture, lifestyle adjustments can profoundly influence the hormonal milieu of the perimenopausal woman. These strategies address the root physiological imbalances that contribute to symptom severity, offering a powerful, evidence-based approach to supporting the body through this natural transition. They provide a foundation upon which any necessary hormonal interventions can be more effectively built.

References

- Toffol, Elena, et al. “The relationship between cortisol and sleep architecture in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 153, 2023.

- Baker, F. C. de Zambotti, M. Colrain, I. M. & Bei, B. “Sleep problems during the menopausal transition ∞ prevalence, impact, and management challenges.” Nature and Science of Sleep, vol. 10, 2018, pp. 73 ∞ 95.

- Lephart, E. D. “Estrogen Action and Gut Microbiome Metabolism in Dermal Health.” Dermatology and Therapy, vol. 12, no. 6, 2022, pp. 1287-1297.

- Shin, H. & Kim, Y. “Gut microbiota and sex hormone interactions in the postmenopausal woman.” Journal of Menopausal Medicine, vol. 28, no. 2, 2022, pp. 55-62.

- Salliss, M. E. et al. “The impact of physical activity and exercise interventions on symptoms for women experiencing menopause ∞ overview of reviews.” BMC Women’s Health, vol. 24, no. 1, 2024, p. 329.

- Stojanovska, L. et al. “The effect of exercise on menopausal symptoms, body composition, and quality of life in menopausal women ∞ a systematic review.” Climacteric, vol. 18, no. 2, 2015, pp. 173-183.

- Berin, E. et al. “Stress, the HPA Axis, and the Female Reproductive System.” Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, vol. 47, no. 3, 2018, pp. 629-640.

- “Perimenopause ∞ Lifestyle Approaches for Maintaining Optimal Health and Wellness.” The Institute for Functional Medicine, 2022.

- “The Role of Diet and Exercise in Managing Menopause Symptoms.” The Centre for Women’s Health, 2023.

- Juppi, H. K. et al. “Climacteric-related symptoms in midlife and beyond ∞ studies using the women’s health questionnaire.” University of Jyväskylä, 2017.

Reflection

You have now explored the intricate biological systems that shape your experience of hormonal health. This knowledge provides a new lens through which to view your body, one that sees symptoms not as adversaries, but as messengers from a complex and intelligent internal environment.

The science reveals that your daily choices are a form of conversation with your own physiology. The foods you select, the way you move, and the quality of your rest are all inputs that your body translates into hormonal signals.

This understanding shifts the focus from a passive endurance of symptoms to an active participation in your own well-being. What signals is your body sending you today? How might you adjust your inputs to better support its equilibrium? This journey of self-inquiry, guided by biological understanding, is the path toward creating a personalized protocol for vitality that is uniquely your own.

Glossary

lifestyle adjustments

endocrine system

insulin sensitivity

physical activity

hormonal health

estrogen and progesterone

bone density

hot flashes

estrogen levels

stress response

perimenopause

hpg axis

hpa axis

lifestyle interventions

phytoestrogens

beta-glucuronidase

the estrobolome

cortisol levels

menopausal hormone therapy

gut microbiome

estrobolome

microbial diversity