Fundamentals

You feel it as a persistent tension, a low-grade hum of anxiety that shadows your days and compromises your nights. It manifests as exhaustion that coffee cannot touch, a mental fog that obscures focus, and a frustrating sense that your body is no longer responding to challenges with the resilience it once possessed.

This experience, this lived reality of being chronically overwhelmed, is a direct transmission from your endocrine system. Your body is speaking a language of hormones, and the message it is sending is one of dysregulation. To understand how to improve your stress response, we must first listen to this conversation happening within you, specifically the dialogue between two foundational systems ∞ the one that manages threat and the one that governs vitality.

At the center of your body’s reaction to any perceived danger, from an urgent deadline to a physical threat, is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. Think of this as your internal emergency broadcast system. It operates through a precise cascade of chemical messengers designed for short-term survival.

The process begins in the hypothalamus, a small but powerful region in your brain that constantly monitors your internal and external environment. When the hypothalamus detects a stressor, it releases Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH). This is the initial alert signal.

CRH travels a short distance to the pituitary gland, the body’s master gland, prompting it to secrete Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) into the bloodstream. ACTH then journeys to the adrenal glands, which sit atop your kidneys. Upon receiving the ACTH signal, the adrenal glands release cortisol, the principal stress hormone.

Cortisol is what you feel. It sharpens your focus, increases your heart rate, and mobilizes sugar into your bloodstream for immediate energy. In a healthy, acute response, this system is life-saving. After the threat passes, a negative feedback loop engages; rising cortisol levels signal the hypothalamus and pituitary to stop releasing CRH and ACTH, and the system stands down. The issue arises when the “off” switch becomes faulty due to chronic activation.

The body’s stress and reproductive systems are in a constant state of biochemical communication, where the function of one directly influences the other.

Working in parallel is another critical system, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This is the architecture of your vitality, governing sexual function, reproductive health, and the production of your primary sex hormones. In men, this axis leads to the production of testosterone in the testes; in women, it orchestrates the cyclical release of estrogen and progesterone from the ovaries.

The mechanism is strikingly similar to the HPA axis. The hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), which signals the pituitary to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These hormones then travel to the gonads (testes or ovaries) to stimulate the production of testosterone or estrogen and progesterone.

These hormones do far more than manage libido and reproduction; they are fundamental to muscle maintenance, bone density, cognitive function, and mood regulation. They are the hormones of resilience, repair, and well-being.

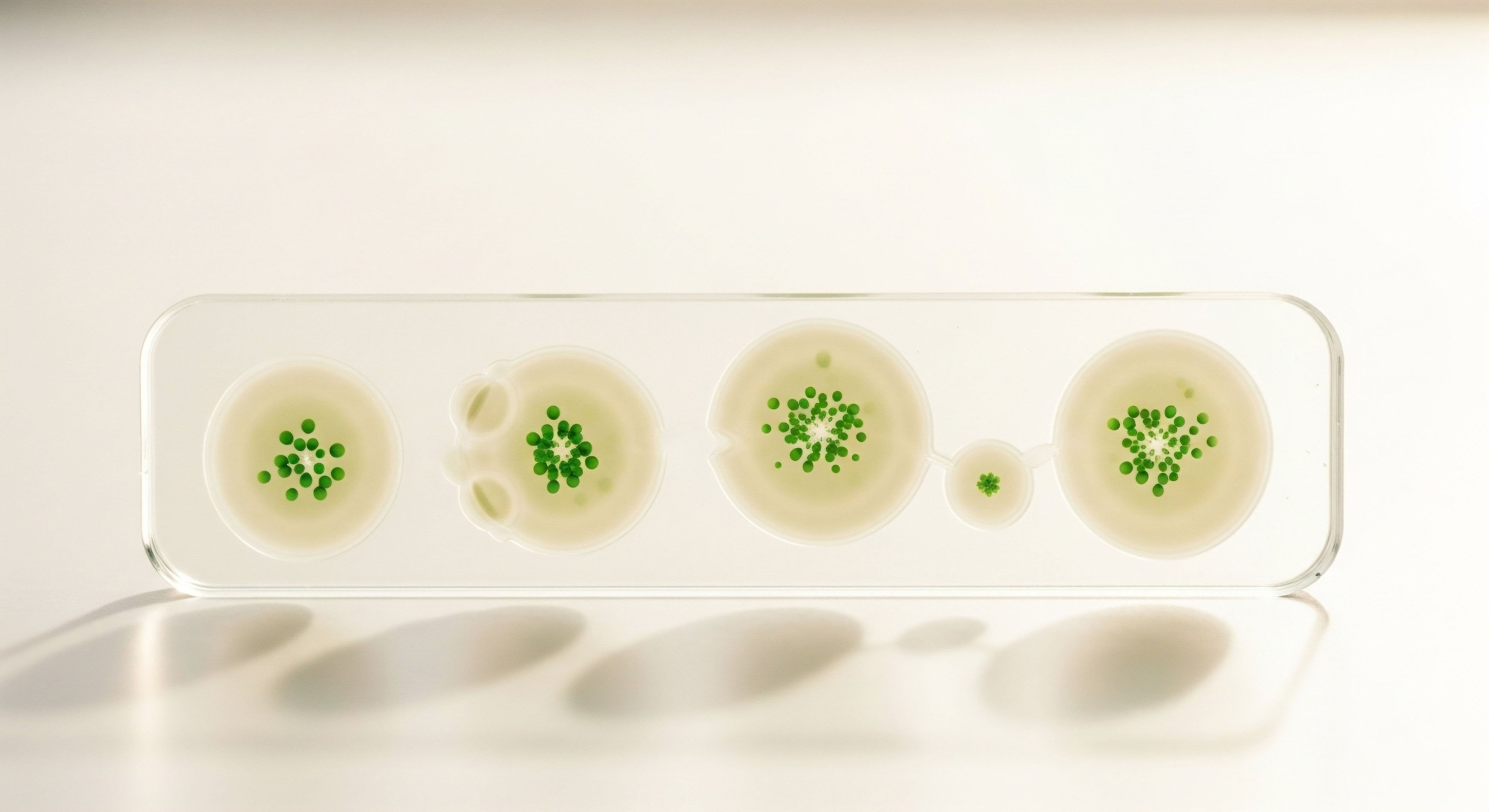

The core of your body’s stress experience lies in the intricate and continuous crosstalk between these two axes. They are not separate entities; they are deeply intertwined, constantly influencing one another. Chronic activation of the HPA axis, with its relentless release of cortisol, sends a powerful inhibitory signal to the HPG axis.

From a biological standpoint, this makes sense ∞ in a state of constant danger, long-term projects like reproduction and repair are put on hold to prioritize immediate survival. High cortisol levels can directly suppress the release of GnRH from the hypothalamus, which in turn reduces the output of LH, FSH, and ultimately, testosterone and estrogen.

This is the biological mechanism behind the loss of libido during stressful periods, and it contributes significantly to the fatigue and low mood associated with burnout. Conversely, the hormones of the HPG axis, particularly testosterone and estrogen, exert a modulating effect on the HPA axis.

Healthy levels of these gonadal hormones help to regulate the sensitivity of the HPA axis, maintaining a balanced stress response. When testosterone and estrogen levels decline, whether due to age or chronic stress, the HPA axis can become dysregulated, overreacting to minor stressors and failing to shut off properly. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle of high stress and low gonadal hormones, leading to a state of diminished wellness and resilience.

Intermediate

The feeling of being perpetually ‘stressed out’ is often the subjective experience of a biological system losing its regulatory capacity. As we age, the elegant communication between the HPA and HPG axes begins to falter. This is a programmed, physiological decline. In men, this manifests as andropause, a gradual reduction in testosterone production.

In women, it is the more turbulent transition of perimenopause and menopause, characterized by fluctuating and ultimately declining levels of estrogen and progesterone. These hormonal shifts directly compromise the HPG axis’s ability to buffer the HPA axis. The result is a heightened sensitivity to stress. The same workplace pressure or family argument that you might have handled with composure a decade ago now triggers a disproportionate and prolonged cortisol response, leaving you feeling anxious, exhausted, and unable to recover.

The Disruption of Endocrine Communication

This disruption is a two-way street. The age-related decline in testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone weakens the calming, regulatory influence on the HPA axis. Simultaneously, the chronic stressors of modern life ∞ incessant digital notifications, financial pressures, lack of restorative sleep ∞ force the HPA axis into a state of continuous overdrive.

This sustained high-cortisol environment actively suppresses the already waning HPG axis, further depressing gonadal hormone production. This feedback loop is where many of the symptoms of hormonal imbalance and chronic stress originate. The brain fog you experience is linked to cortisol’s impact on the hippocampus, a brain region essential for memory, which is also rich in receptors for estrogen and testosterone.

The irritability and mood swings are tied to the fluctuating balance of these hormones and their influence on neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine. The persistent fatigue is the metabolic cost of a body constantly prepared for a threat that never fully resolves.

Recalibrating the System with Hormonal Optimization

Hormonal optimization protocols are designed to intervene in this cycle. The objective is to restore the HPG axis’s side of the conversation, providing the necessary biochemical signals to help re-regulate the HPA axis. By reintroducing foundational hormones to physiologic levels, these therapies can help re-establish the body’s natural stress-buffering capacity. This is about restoring a system’s balance, allowing it to function with greater efficiency and resilience.

Optimizing gonadal hormones provides the HPA axis with the regulatory feedback it needs to temper its response to daily stressors.

For men experiencing the symptoms of low testosterone, a common protocol involves Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT). This is a carefully managed process designed to restore testosterone to a healthy, youthful range.

- Testosterone Cypionate ∞ This is a bioidentical form of testosterone, typically administered via weekly intramuscular or subcutaneous injections. The goal is to create stable blood levels of testosterone, avoiding the peaks and troughs that can come with other delivery methods. This stability is what allows the body to re-adapt to a new hormonal baseline.

- Gonadorelin ∞ During TRT, the brain may sense the presence of external testosterone and reduce its own signals (LH and FSH) to the testes. Gonadorelin, a synthetic form of GnRH, is used to gently stimulate the pituitary, maintaining the natural signaling pathway and preserving testicular function and fertility.

- Anastrozole ∞ Testosterone can be converted into estrogen in the body through a process called aromatization. While some estrogen is necessary for men’s health, excess levels can cause side effects. Anastrozole is an aromatase inhibitor, a medication used in small doses to block this conversion, ensuring the optimal balance between testosterone and estrogen.

For women navigating the complexities of perimenopause and menopause, hormonal therapy is tailored to their specific needs, addressing the decline in estrogen, progesterone, and often, testosterone.

Female Hormonal Recalibration Protocols

| Therapeutic Agent | Purpose and Mechanism |

|---|---|

|

Testosterone Cypionate (Low Dose) |

Administered in small weekly subcutaneous injections, testosterone for women addresses symptoms like low libido, fatigue, and loss of muscle mass. It plays a key role in energy, mood, and cognitive function, contributing to an overall sense of vitality and resilience. |

|

Progesterone |

Progesterone has a calming effect on the nervous system and is essential for sleep quality. Its use, particularly in post-menopausal women, helps to balance the effects of estrogen and provides significant benefits for mood stability and stress modulation. It directly interacts with GABA receptors in the brain, promoting relaxation. |

|

Estrogen Therapy |

Restoring estrogen levels is foundational for addressing many menopausal symptoms, including hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and bone density loss. Estrogen also has profound effects on brain function and HPA axis regulation, helping to stabilize mood and improve cognitive clarity. |

By carefully re-establishing these hormonal foundations, the body’s internal environment begins to shift. The HPG axis is no longer suppressed, and its renewed output provides the necessary negative feedback to the HPA axis. This recalibration can lead to a more measured cortisol response, improved sleep, better mood, and a renewed capacity to handle life’s challenges without becoming overwhelmed.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the interplay between hormonal optimization and stress resilience requires a move beyond systemic descriptions to the molecular and neurobiological level. The efficacy of these interventions is rooted in the direct modulation of receptor sensitivity and gene expression within the central nervous system, particularly in the limbic structures that govern the HPA axis.

The interaction is a complex dance of allosteric modulation, receptor trafficking, and transcriptional regulation, where gonadal steroids and therapeutic peptides fundamentally alter the brain’s capacity to process and recover from stress.

Gonadal Steroid Modulation of Glucocorticoid Receptor Function

The core mechanism through which stress exerts its effects is the binding of cortisol to its two primary receptors in the brain ∞ the high-affinity mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) and the lower-affinity glucocorticoid receptor (GR). MRs are typically occupied under basal cortisol conditions, managing the body’s normal homeostatic tone.

GRs become significantly occupied only when cortisol levels rise during a stress response, and it is their activation that mediates the majority of cortisol’s effects, including the crucial negative feedback that shuts the HPA axis down. The functionality of these receptors is not static; it is dynamically modulated by the surrounding hormonal milieu, most notably by testosterone and estradiol.

Research into testosterone’s influence on the HPA axis has yielded nuanced findings. Some clinical data suggests that testosterone administration can blunt the cortisol response to a CRH challenge, indicating a suppressive effect at the level of the adrenal gland itself.

In these studies, even as ACTH levels rose, the adrenal output of cortisol was diminished in the testosterone-replete state. This points to a direct inhibitory action of testosterone on adrenal steroidogenesis. Other studies, however, have shown that in the context of a social-evaluative stressor, exogenous testosterone can actually increase the cortisol response, particularly in men with high trait dominance.

This suggests a more complex, context-dependent role. Testosterone may increase the perceived salience of a status threat, priming the HPA axis for a more robust response. These divergent findings highlight that testosterone’s effect on the stress axis is a function of both direct physiological inhibition and indirect psychological modulation.

How Does Estrogen Influence the Female Stress Response?

In the female brain, estradiol is a primary regulator of HPA axis function. Estradiol has been shown to influence the expression and function of both CRH and its receptors. During the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, when estradiol levels are rising, women often exhibit a lower cortisol response to psychosocial stress compared to the luteal phase.

This suggests estradiol may enhance the negative feedback sensitivity of the HPA axis. Mechanistically, estradiol can increase the expression of GRs in key brain regions like the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, the very areas responsible for inhibiting the HPA axis. Progesterone and its neuroactive metabolite, allopregnanolone, add another layer of regulation.

Allopregnanolone is a potent positive allosteric modulator of the GABA-A receptor, the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter system in the brain. By enhancing GABAergic inhibition, progesterone and allopregnanolone can exert a powerful calming effect, directly tempering HPA axis activity. The decline of these hormones during menopause removes this layer of neurochemical buffering, contributing to the heightened stress sensitivity observed in this population.

Peptide-Based Interventions for Stress Axis Modulation

A newer frontier in wellness protocols involves the use of growth hormone secretagogues (GHS), such as the peptide combination of Ipamorelin and CJC-1295. These peptides are designed to stimulate the body’s own production of growth hormone (GH) from the pituitary gland in a manner that mimics natural pulsatile release.

Their value in a stress-resilience context lies in their high degree of specificity. Growth hormone itself has a complex relationship with the HPA axis, but many first-generation GHS peptides had the undesirable effect of also stimulating the release of ACTH and cortisol. This created a situation where the benefits of increased GH could be offset by an iatrogenic activation of the stress axis.

Growth Hormone Secretagogue Selectivity

| Peptide | Mechanism of Action | Impact on Cortisol |

|---|---|---|

|

A highly selective, third-generation GHRP (Growth Hormone Releasing Peptide) that binds to the ghrelin receptor (GHS-R1a) in the pituitary to stimulate GH release. |

Minimal to no impact on ACTH or cortisol secretion, even at high doses. This selectivity makes it a preferred agent for promoting GH benefits without activating the HPA axis. |

|

|

A GHRH (Growth Hormone Releasing Hormone) analogue. It stimulates the GHRH receptor on the pituitary, increasing the amplitude of the natural GH pulses initiated by peptides like Ipamorelin. |

Does not directly stimulate cortisol release. It works on a separate receptor pathway from the one that triggers ACTH production. |

The precision of third-generation peptides allows for the stimulation of growth hormone pathways without the confounding activation of the cortisol-driven stress axis.

The combination of Ipamorelin and CJC-1295 provides a synergistic effect, leading to a robust and sustained increase in both GH and Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1). The downstream effects of this increased GH/IGF-1 signaling ∞ improved sleep architecture (particularly deep sleep), enhanced tissue repair, and better metabolic function ∞ all contribute to a greater capacity for physiological recovery.

By improving the fundamental processes of repair and regeneration, these peptides help to build a more resilient biological foundation, making the system less susceptible to the catabolic effects of chronic stress. The key is that they achieve this without directly stimulating cortisol, thereby separating the anabolic benefits of GH from the catabolic signaling of the stress axis. This represents a highly targeted intervention to improve wellness by enhancing recovery pathways, a stark contrast to simply managing stress symptoms.

References

- Rubinow, David R. et al. “Testosterone suppression of CRH-stimulated cortisol in men.” Neuropsychopharmacology, vol. 30, no. 10, 2005, pp. 1956-62.

- van Anders, Sari M. et al. “Effects of exogenous testosterone on cortisol and affective responses to social-evaluative stress in dominant men.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 85, 2017, pp. 143-52.

- Viau, V. “Functional cross-talk between the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal and -adrenal axes.” Journal of Neuroendocrinology, vol. 14, no. 6, 2002, pp. 506-13.

- Raadsma, S. J. et al. “Effects of estrogen versus estrogen and progesterone on cortisol and interleukin-6.” Menopause, vol. 20, no. 10, 2013, pp. 1048-54.

- Kirschbaum, C. et al. “Sex-specific effects of social support on cortisol and subjective responses to acute psychological stress.” Psychosomatic Medicine, vol. 57, no. 1, 1995, pp. 23-31.

- Handa, Robert J. et al. “Androgen regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis ∞ mechanism and implications for stress responsiveness.” Hormones and Behavior, vol. 61, no. 5, 2012, pp. 698-706.

- Raab, W. H. et al. “Ipamorelin, the first selective growth hormone secretagogue.” European Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 139, no. 5, 1998, pp. 552-61.

- Zouboulis, C. C. et al. “Sexual hormones in human skin.” Hormone and Metabolic Research, vol. 39, no. 2, 2007, pp. 85-95.

- McEwen, Bruce S. “Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation ∞ central role of the brain.” Physiological Reviews, vol. 87, no. 3, 2007, pp. 873-904.

- Sapolsky, Robert M. et al. “How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 21, no. 1, 2000, pp. 55-89.

Reflection

You have now seen the intricate biological architecture that connects your hormonal vitality to your experience of stress. The symptoms you feel are not isolated events; they are data points, signals from a complex and interconnected system. Understanding the conversation between your HPA and HPG axes is the first, powerful step toward changing its content and its tone.

The information presented here provides a map of the underlying territory. The next step involves charting your own unique position on that map. Your biology, your history, and your goals create a context that is entirely your own. The path toward reclaiming your resilience and function begins with this knowledge, prompting a deeper inquiry into your personal health journey and the personalized strategies that will allow you to recalibrate your system for optimal well-being.