Fundamentals

The conversation about aging often revolves around external markers, the visible shifts in energy, skin, and physical capacity. Your personal experience of these changes is the primary data point. It is the lived reality that science seeks to understand. When we explore the link between our hormones and cardiovascular health, we are examining the very engine of our vitality.

The subtle, creeping fatigue, the changes in physical resilience, and the sense that your body operates by a different set of rules are all valid, observable phenomena. These feelings are the subjective translation of objective biological events.

At the heart of this internal shift lies the endocrine system, the body’s master communication network, which uses hormones as its chemical messengers to regulate everything from our metabolism to our mood. As we age, the production of these key messengers, including testosterone and estrogen, naturally declines. This process is a systemic recalibration that extends far beyond reproductive health, touching every aspect of our physiology, most critically the silent, intricate workings of our cardiovascular system.

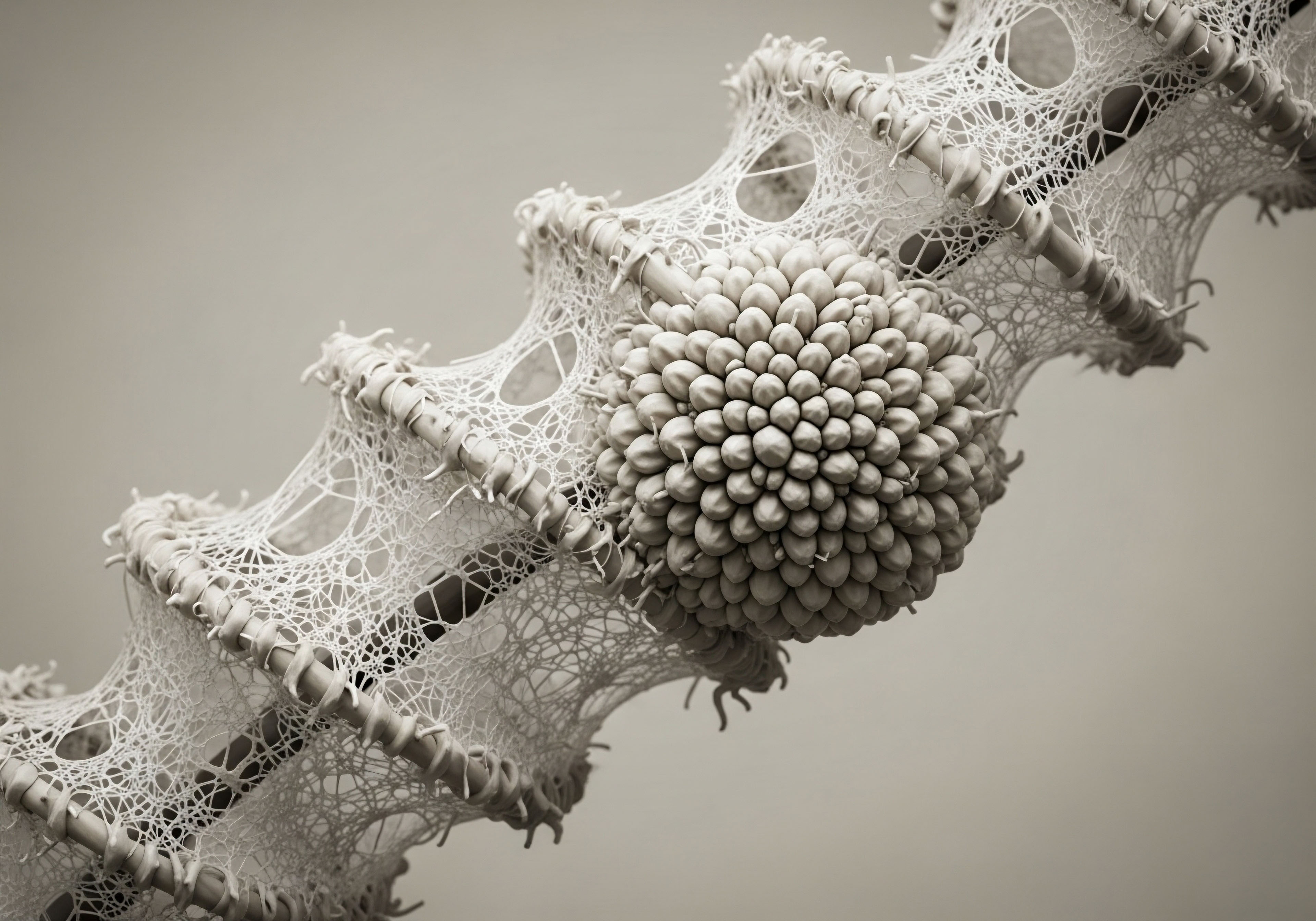

To understand how hormonal optimization can influence cardiovascular risk, we must first look to the inner lining of our blood vessels, a delicate, single-cell-thick layer called the endothelium. Consider the endothelium as the gatekeeper of vascular health. A healthy endothelium is flexible, smooth, and actively prevents the formation of clots and plaque.

It accomplishes this by producing a critical molecule called nitric oxide, which signals the surrounding smooth muscle to relax, promoting healthy blood flow and pressure. Sex hormones, particularly estrogen and testosterone, are powerful guardians of endothelial function. Estrogen directly stimulates the production of nitric oxide, acts as a potent antioxidant, and helps maintain a favorable lipid profile.

In men, testosterone contributes to vascular health through similar mechanisms, partly through its own direct action and partly by being converted into estrogen within the tissues by an enzyme called aromatase. The age-related decline in these hormones removes a layer of this intrinsic protection. The endothelium can become stiff and dysfunctional, a condition that precedes the development of atherosclerosis, the hardening and narrowing of the arteries that is the foundation of most cardiovascular disease.

The gradual decline of sex hormones with age directly impacts the health of our blood vessel linings, setting the stage for future cardiovascular events.

This biological reality forms the basis of our inquiry. The symptoms of hormonal change you may feel are inextricably linked to these cellular-level changes. The process of reclaiming vitality, therefore, begins with understanding this connection. It is about recognizing that the language of symptoms and the language of cellular biology are telling the same story.

By supporting the body’s hormonal environment, we are directly addressing the foundational mechanisms that protect the integrity of our vast vascular network. This is the personal journey into your own biology, a path toward comprehending the systems that govern your function and, ultimately, toward preserving the silent, steady beat of your cardiovascular health.

Intermediate

As we move from the foundational ‘why’ to the clinical ‘how,’ we examine the specific strategies used to support the body’s endocrine system. These hormonal optimization protocols are designed to re-establish a physiological environment that is more characteristic of youthful vitality, with the explicit goal of mitigating the downstream effects of age-related hormonal decline, including cardiovascular risk. The approach is distinct for men and women, tailored to the unique hormonal architecture of each sex.

Hormonal Optimization for Men

For men, the conversation centers on Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT). The decline of testosterone, or hypogonadism, is associated with a constellation of symptoms including fatigue, reduced muscle mass, and mood changes, alongside an increased risk for metabolic issues that contribute to cardiovascular disease.

The clinical data on the cardiovascular safety of TRT has been a subject of intense study and some controversy. Early retrospective studies raised concerns about a potential increase in adverse cardiovascular events. However, more recent and robust evidence from multiple meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) has provided a more reassuring picture.

These larger analyses have generally found that TRT in men with low testosterone does not increase the risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death, stroke, or myocardial infarction.

A standard protocol for TRT involves more than simply replacing testosterone. It is a systemic approach designed to maintain balance.

- Testosterone Cypionate ∞ Typically administered as a weekly intramuscular injection, this forms the cornerstone of the therapy, directly restoring testosterone levels.

- Gonadorelin ∞ This peptide is used to stimulate the pituitary gland, helping to maintain the body’s own natural testosterone production pathway and preserving testicular function and fertility.

- Anastrozole ∞ Anastrozole is an aromatase inhibitor.

As discussed previously, some testosterone is converted to estrogen, which is beneficial for men’s cardiovascular health. However, in a state of testosterone replacement, this conversion can become excessive, leading to an imbalance. Anastrozole modulates this conversion, preventing potential side effects associated with elevated estrogen in men while maintaining its protective effects.

Despite the reassuring data on major events, some studies have noted a higher incidence of certain adverse effects, such as atrial fibrillation or pulmonary embolism, in men receiving testosterone. This underscores the principle that TRT is a personalized medical intervention that must be undertaken with careful consideration of an individual’s baseline cardiovascular health and risk factors.

What Is the “timing Hypothesis” in Female Hormone Therapy?

For women, the dialogue around hormone therapy (HT) and cardiovascular risk is dominated by the “timing hypothesis.” This concept is critical for understanding the evolution of clinical thought. Initial findings from the large-scale Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial, published in the early 2000s, reported an increased risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and blood clots in postmenopausal women receiving combined estrogen and progestin therapy.

This led to a sharp decline in the use of HT. However, a critical feature of the WHI study was that the average age of participants was 63, many of whom were more than a decade past the onset of menopause.

Starting hormone therapy near the onset of menopause appears to offer cardiovascular protection, a benefit that is lost or even reversed when therapy begins many years later.

Subsequent analyses of the WHI data and new, dedicated clinical trials have revealed a different story. When HT is initiated in women who are closer to the age of menopause (typically within 10 years of their final menstrual period), the cardiovascular outcomes are much more favorable.

Some studies show a significant reduction in the combined risk of mortality, heart failure, and myocardial infarction in this group. This timing hypothesis suggests that estrogen provides a protective effect on blood vessels that are still relatively healthy, but it may have a destabilizing effect on established atherosclerotic plaques in older women.

Protocols for women are tailored to their menopausal status and individual needs:

| Trial/Analysis | Population Studied | Key Cardiovascular Finding |

|---|---|---|

| WHI (Original) | Older postmenopausal women (avg.

age 63) |

Increased risk of CHD, stroke, and venous thromboembolism with combined therapy. |

| WHI (Secondary Analysis) | Data stratified by age/time since menopause | Reduced or neutral CHD risk for women starting therapy closer to menopause. |

| Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study (DOPS) | Healthy, recently postmenopausal women | Significantly reduced risk of mortality, heart failure, or MI with early HT. |

Growth Hormone Peptides a Frontier of Research

A separate category of intervention involves growth hormone secretagogues, such as the peptide combination of Ipamorelin and CJC-1295. These are not hormones themselves but peptides that stimulate the pituitary gland to release more of the body’s own growth hormone.

Research, primarily in animal models, suggests that enhancing growth hormone release may have benefits for tissue repair, including for cardiac tissue following an injury like a myocardial infarction. However, this area of therapy is much less established than sex hormone replacement.

The FDA has issued warnings regarding the potential cardiovascular risks of certain peptides, noting that substances like CJC-1295 can increase heart rate and lower blood pressure, posing a danger to individuals with pre-existing heart conditions. Long-term human safety data is scarce, and these protocols are not considered a primary strategy for cardiovascular risk reduction at this time.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of hormonal optimization and its influence on cardiovascular risk requires a granular examination of the molecular interactions between sex hormones and the vascular endothelium. The endothelium is a dynamic, metabolically active organ that serves as the critical interface between the bloodstream and the vessel wall.

Its functional integrity is paramount, and its dysfunction is a sentinel event in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Sex steroids exert profound and pleiotropic effects on endothelial cells, modulating gene expression, signaling cascades, and the local inflammatory milieu. Understanding these mechanisms reveals how hormonal decline initiates a cascade of pro-atherogenic changes and how thoughtful intervention can potentially arrest or reverse this process.

The Central Role of Nitric Oxide Bioavailability

The cornerstone of endothelial health is the bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO), a potent vasodilator and anti-inflammatory molecule synthesized by the enzyme endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). Estrogen, acting through its primary receptor, ERα, directly upregulates the expression and activity of eNOS. This occurs via both genomic and non-genomic pathways.

The genomic pathway involves estrogen response elements in the eNOS gene promoter, leading to increased transcription. The non-genomic pathway is a rapid activation of eNOS via kinase signaling cascades, such as the PI3K/Akt pathway, leading to immediate NO production. This dual-action mechanism provides a robust system for maintaining vascular tone and preventing platelet aggregation and leukocyte adhesion, the initial steps of plaque formation.

Testosterone’s role in this process is multifaceted. It can also induce vasodilation, partly through NO-dependent pathways. A crucial component of its cardioprotective effect in men, however, is its peripheral conversion to estradiol by the aromatase enzyme, which is present in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells.

This locally produced estradiol then acts on ERα receptors to promote eNOS activity, effectively allowing men to harness the primary vascular benefits of estrogen. This explains why therapies that block aromatase too aggressively can be detrimental and why a balanced hormonal profile is essential.

How Do Sex Hormones Influence Vascular Inflammation?

Atherosclerosis is fundamentally an inflammatory disease. The age-related decline in sex hormones fosters a pro-inflammatory state within the vasculature. Estrogen has direct anti-inflammatory properties, suppressing the expression of key adhesion molecules (like VCAM-1 and ICAM-1) that allow inflammatory cells to stick to the endothelium and infiltrate the vessel wall.

It also reduces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α. The loss of estrogen during menopause removes this anti-inflammatory shield, contributing to the acceleration of atherosclerotic processes observed in postmenopausal women.

In postmenopausal women, the hormonal balance often shifts towards a relatively more androgenic state, as ovarian estrogen production ceases while androgen production continues from the ovaries and adrenal glands. A higher ratio of free testosterone to estradiol in postmenopausal women has been associated with impaired endothelial function and an increased burden of subclinical atherosclerosis, suggesting that in the female vascular environment, an androgen-dominant milieu can be pro-atherogenic.

Sex hormones directly regulate the genetic expression of inflammatory molecules within blood vessels, influencing the development of atherosclerotic plaque.

This contrasts with the situation in men, where healthy testosterone levels are associated with lower levels of inflammatory markers. Low testosterone in men is linked to an increase in visceral adipose tissue, which is itself a major source of inflammatory cytokines, creating a vicious cycle of hormonal decline, inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction that drives cardiovascular risk.

| Hormone | Primary Receptor | Key Cellular Actions | Net Vascular Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol (E2) | ERα, ERβ, GPER | Increases eNOS expression and activity; Decreases expression of adhesion molecules (VCAM-1); Reduces inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α); Protects from lipid oxidation. | Anti-atherogenic, Vasodilatory, Anti-inflammatory. |

| Testosterone (T) | Androgen Receptor (AR) | Induces vasodilation (partly NO-dependent); Serves as a prohormone for estradiol via aromatase; Modulates inflammatory markers. | Cardioprotective (in a balanced state); dependent on aromatization. |

| Progesterone | Progesterone Receptor (PR) | Effects are complex and can depend on the specific progestin used; some may oppose estrogen’s beneficial vascular effects. | Variable; less defined than estrogen or testosterone. |

The “timing hypothesis” can also be understood through this molecular lens. In younger, healthier vessels, estrogen therapy restores the protective mechanisms of NO production and anti-inflammation. In older vessels with established, complex atherosclerotic plaques, the sudden reintroduction of estrogen may alter the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) within the plaque, potentially leading to plaque instability and rupture.

The biological context of the vascular bed dictates the ultimate outcome of the hormonal intervention. Therefore, hormonal optimization is a strategy of restoring cellular communication and function within a receptive system, a principle that is fundamental to its potential for mitigating cardiovascular risk in aging adults.

References

- Stanhewicz, Anna E. et al. “Sex differences in endothelial function important to vascular health and overall cardiovascular disease risk across the lifespan.” American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, vol. 315, no. 6, 2018, pp. H1569-H1588.

- Mendelsohn, Michael E. and Richard H. Karas. “The protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 340, no. 23, 1999, pp. 1801-1811.

- Rossouw, Jacques E. et al. “Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women ∞ principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial.” JAMA, vol. 288, no. 3, 2002, pp. 321-333.

- Schierbeck, Louise C. et al. “Effect of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular events in recently postmenopausal women ∞ randomised trial.” The BMJ, vol. 345, 2012, e6409.

- Lincoff, A. Michael, et al. “Cardiovascular Safety of Testosterone-Replacement Therapy.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 389, no. 2, 2023, pp. 107-117.

- Spann, Mark A. et al. “The Effect of Testosterone on Cardiovascular Disease and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Men ∞ A Review of Clinical and Preclinical Data.” Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, vol. 10, no. 3, 2023, p. 100.

- Vigen, Rebecca, et al. “Association of testosterone therapy with mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in men with low testosterone levels.” JAMA, vol. 310, no. 17, 2013, pp. 1829-1836.

- Teichmann, J. et al. “Long-acting growth hormone releasing hormone (GHRH) analog CJC-1295 increases growth hormone and IGF-I secretion in healthy adults.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 91, no. 3, 2006, pp. 799-805.

- “Insights into the Tesamorelin, Ipamorelin, and CJC-1295 Peptide Blend.” Peptide Sciences, 12 Feb. 2025.

- Wu, Z. et al. “Endogenous Sex Hormones and Endothelial Function in Postmenopausal Women and Men ∞ The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 98, no. 8, 2013, pp. 3399-3408.

Reflection

The information presented here maps the intricate biological pathways that connect your endocrine system to your cardiovascular health. This knowledge serves as a powerful tool, moving the conversation from a passive experience of aging to a proactive engagement with your own physiology.

The journey through this clinical science is not about finding a universal answer, but about illuminating the specific questions you can bring to a partnership with a qualified medical professional. Your unique health history, your personal risk factors, and your subjective experience are the essential context for any therapeutic decision.

The ultimate goal is to compose a health strategy that is yours alone, one that is built on a foundation of deep biological understanding and aimed at sustaining a long and vibrant life.