Fundamentals

You have followed your therapeutic protocol with precision. The weekly injection is administered correctly, yet the site remains tender, displays persistent bruising, or seems slow to return to normal. This experience is a valid biological signal from your body, a direct communication about its internal environment.

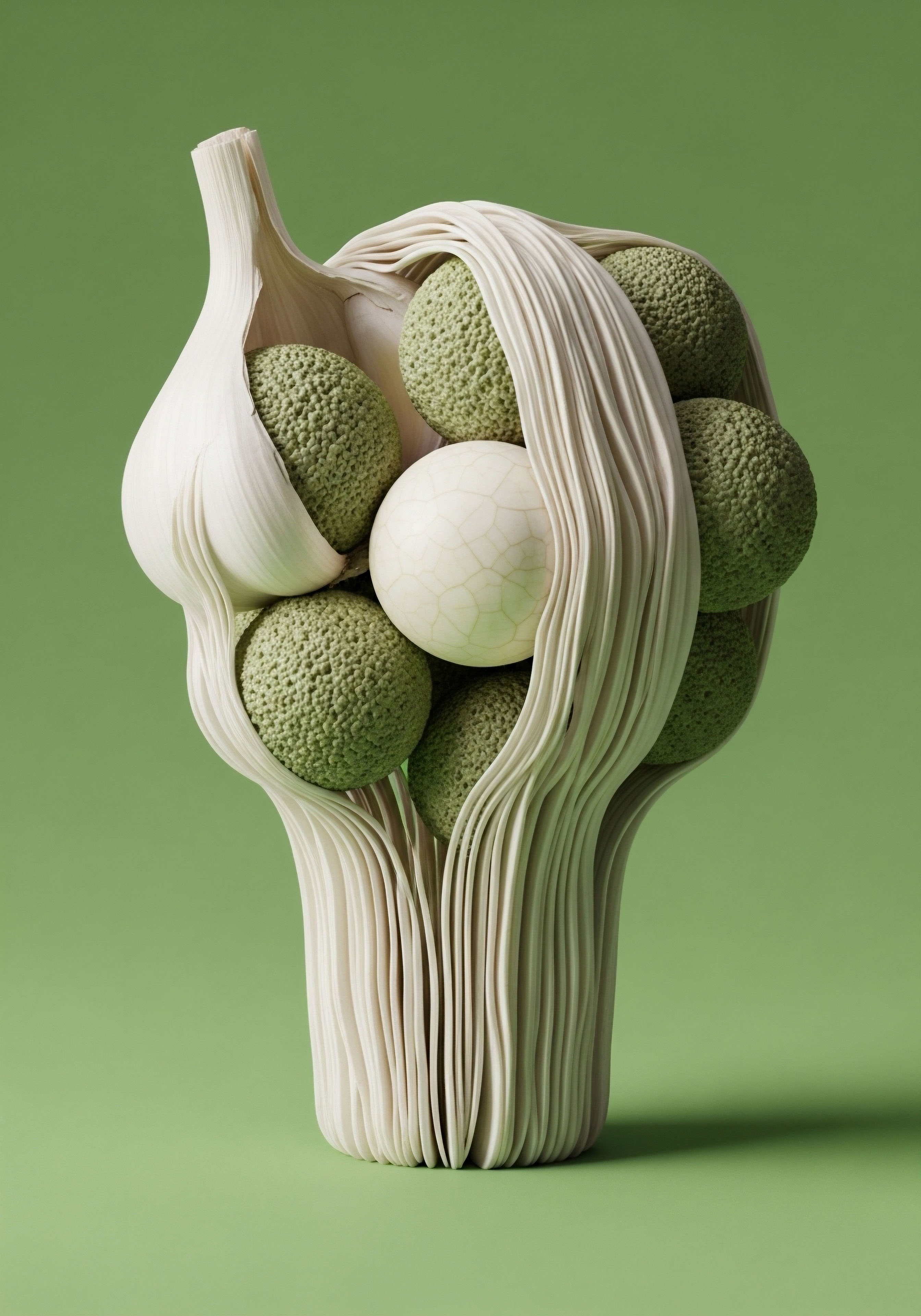

The process of healing, even from a minor puncture, is a complex and resource-intensive event orchestrated by the endocrine system. Your hormones act as the conductors of this intricate cellular orchestra, and when they are out of balance, the symphony of repair can become dissonant.

Understanding this connection begins with appreciating that healing is an active process. Your body must first manage the initial trauma, then clear away damaged cells, and finally, construct new tissue. Each of these stages is governed by specific hormonal messengers.

When the levels of these messengers are either too high or too low, the entire timeline and quality of the repair process are altered. This is the foundational reason why a systemic hormonal imbalance can manifest as a localized healing problem.

The Primary Hormonal Influences on Tissue Repair

Four key hormones are central to the body’s ability to recover from the physical stress of an injection. Their balance dictates the efficiency and outcome of the healing process at the most fundamental level.

Cortisol the Resource Manager

Cortisol is produced by the adrenal glands in response to stress. Its primary function in this context is to manage resources. When the body perceives stress, whether from life events or from an underlying health condition, cortisol levels rise.

Elevated cortisol redirects the body’s energy away from processes it deems non-essential for immediate survival, including complex, long-term building projects like tissue repair. Sustained high cortisol can suppress the local immune response needed to protect the injection site and can slow down the cellular regeneration required for a full recovery. This can result in a site that stays inflamed or bruised for longer than expected.

Estrogen the Inflammatory Regulator

Estrogen plays a vital role in modulating inflammation, which is the first and most critical stage of healing. Think of inflammation as the body’s emergency response team. An effective response is quick, targeted, and resolves once the area is secure. Estrogen helps ensure this efficiency.

It fine-tunes the activity of immune cells, preventing an excessive or prolonged inflammatory reaction. In a state of estrogen deficiency, such as during menopause, the inflammatory response can become dysregulated, leading to more cellular damage and a delay in the transition to the rebuilding phase of healing.

The state of your hormonal environment directly dictates the speed and quality of your body’s response to any physical injury, including routine injections.

Growth Hormone the Master Builder

As its name implies, Growth Hormone (GH) is the body’s primary signal for tissue construction and regeneration. It stimulates the cellular activities required to build new collagen, repair blood vessels, and form new skin. When GH levels are optimal, the rebuilding phase of healing is robust and efficient. A deficiency in GH, however, can lead to a sluggish repair process, where the injection site fails to regenerate tissue effectively, sometimes leaving a small indentation or discoloration.

Testosterone the Anabolic Driver

Testosterone is a powerful anabolic hormone, meaning it promotes the synthesis of new tissues, particularly protein-based structures like muscle and the collagen matrix in skin. This anabolic drive is essential for the rebuilding phase of healing. Concurrently, testosterone can also amplify the initial inflammatory response.

This creates a dual role where its balance becomes paramount. Sufficient levels are needed for tissue construction, but excessive levels, especially in relation to estrogen, can contribute to a more aggressive and prolonged inflammatory phase, interfering with the very healing it is meant to support.

- Prolonged Redness and Swelling This can be a sign of an unchecked inflammatory response, potentially influenced by low estrogen or an imbalanced testosterone-to-estrogen ratio.

- Excessive Bruising Bruising results from damage to small blood vessels. Hormonal imbalances can affect capillary fragility and the efficiency of the initial clotting and cleanup process, leading to more significant bruising.

- Slow Tissue Regeneration If the injection site remains indented or takes a very long time to feel smooth again, it may point to insufficient anabolic signaling from hormones like Growth Hormone or a suboptimal testosterone balance.

- Persistent Tenderness While some initial tenderness is normal, sensitivity that lasts for many days may indicate ongoing low-grade inflammation, a hallmark of a hormonally impeded healing process.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational roles of individual hormones, a deeper understanding of injection site healing requires examining the precise mechanisms through which these biochemical messengers interact with the cellular healing cascade. The healing process is a meticulously sequenced biological program, and hormonal imbalances interfere with this program at specific, identifiable points. The outcome of an injection is a direct reflection of the body’s ability to execute two critical phases ∞ the initial inflammatory phase and the subsequent proliferative phase.

How Hormones Modulate the Inflammatory Phase

The initial response to the needle puncture is inflammation. Its purpose is to control bleeding, prevent infection, and call specialized cells to the area to begin cleanup. The quality of this inflammatory response is a powerful determinant of the entire healing outcome. An efficient, well-regulated response sets the stage for rapid recovery. A dysregulated, excessive, or prolonged response creates cellular damage and delays the start of rebuilding.

Estrogen exerts a profound regulatory effect on this phase. It functions by tempering the activity of neutrophils, the first immune cells to arrive at an injury site. By modulating their chemotaxis (the chemical signaling that calls them to the area), estrogen ensures that the response is proportional to the injury.

It also reduces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6). This action calms the local environment, minimizes collateral damage to healthy tissue, and allows for a quicker transition to the next phase. In women with optimized hormonal profiles, this translates to less swelling and redness at the injection site.

Conversely, androgens like testosterone can amplify the inflammatory response. Research indicates that testosterone can enhance the signals that promote inflammation, in part through pathways involving mediators like Smad3. This can lead to a more robust and sustained presence of inflammatory cells.

While some inflammation is necessary, an excessive response can increase the breakdown of the local tissue matrix, leading to more significant tenderness and a slower resolution of the initial injury. This is a key reason why protocols for men on Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) often include measures to manage estrogen levels. Maintaining an appropriate testosterone-to-estrogen ratio is vital for controlling this initial inflammatory surge.

Effective healing depends on a hormonal symphony that first manages inflammation with precision and then provides strong anabolic signals for reconstruction.

The Proliferative Phase Where Hormones Drive Reconstruction

Once the initial inflammation is controlled, the proliferative or rebuilding phase begins. This is where anabolic hormones become the dominant players. The goal is to build new tissue, including collagen for structural support and new blood vessels (angiogenesis) to supply the area with nutrients. Testosterone, Growth Hormone (GH), and Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) are the primary drivers of this process.

Testosterone’s anabolic properties directly stimulate fibroblasts to produce collagen, the protein that gives skin its strength and structure. GH works systemically and locally to promote cell division and regeneration. A significant portion of GH’s effects are mediated by IGF-1, which is a powerful signal for cell growth and proliferation.

Effective healing requires robust signaling from this anabolic team. If these signals are weak due to a deficiency, or if they are overridden by a persistent inflammatory state caused by high cortisol or a hormonal imbalance, the rebuilding process will be slow and incomplete.

Clinical Protocols and Healing Outcomes

Understanding these mechanisms provides a clear rationale for the structure of modern hormonal optimization protocols.

- TRT for Men The standard protocol of Testosterone Cypionate combined with an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole is designed to address this balance. The testosterone provides the necessary anabolic signal for tissue health and repair, while the Anastrozole prevents excessive conversion to estrogen, which could cause other issues, and helps maintain a healthy testosterone-to-estrogen ratio to avoid unchecked inflammation. The inclusion of Gonadorelin supports the body’s own hormonal production, contributing to a more stable internal milieu conducive to healing.

- Hormone Therapy for Women For peri- and post-menopausal women, therapy often involves replacing both estrogen and progesterone, and sometimes a small amount of testosterone. Restoring estrogen levels directly improves the regulation of the inflammatory phase of healing, as supported by clinical observations of accelerated wound repair in women on hormone therapy. The addition of testosterone supports the anabolic, tissue-building phase that can decline with age.

- Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy The use of peptides like Sermorelin or Ipamorelin/CJC-1295 is a direct intervention to enhance the proliferative phase of healing. These agents stimulate the body’s own production of GH, thereby boosting the signals for cell regeneration and tissue repair. For individuals with slow-healing injection sites, this can be a targeted strategy to improve the body’s rebuilding capacity.

| Hormone | Impact on Inflammatory Phase | Impact on Proliferative (Rebuilding) Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Estrogen |

Regulates and reduces excessive inflammation by modulating neutrophil and cytokine activity. |

Supports a healthy tissue matrix and prepares the environment for rebuilding. |

| Testosterone |

Can amplify the inflammatory response, potentially prolonging this phase if not balanced with estrogen. |

Provides a strong anabolic signal for collagen synthesis and tissue construction. |

| Cortisol |

Suppresses the overall immune and inflammatory response, which can impair the necessary cleanup functions. |

Inhibits fibroblast activity and collagen formation, directly slowing down rebuilding. |

| Growth Hormone / IGF-1 |

Plays a lesser role in the initial phase, but a healthy inflammatory response is required for its signals to be effective later. |

Acts as the primary driver of cell proliferation, regeneration, and new tissue formation. |

Academic

An academic exploration of how hormonal imbalances affect injection site healing necessitates a systems-biology perspective, moving beyond the action of single hormones to the integrated function of the body’s major signaling networks. The local cellular event of wound repair is a microcosm of the body’s systemic endocrine health.

The outcome is determined by the complex interplay between the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, and their downstream effects on cellular receptors, cytokine expression, and local steroidogenesis within the wound microenvironment itself.

Endocrine Axis Crosstalk the HPA and HPG Influence

The body’s response to both the stress of an injection and the underlying condition requiring therapy is governed by two master regulatory systems.

The HPA axis is the central stress response system. Chronic activation, whether from psychological stress, illness, or poor metabolic health, results in sustained elevated levels of glucocorticoids, primarily cortisol. From a mechanistic standpoint, cortisol exerts its inhibitory effects on healing through several pathways.

It downregulates the expression of genes responsible for producing collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins in fibroblasts. Furthermore, it suppresses the function of key immune cells like macrophages, delaying the critical transition from the inflammatory to the proliferative stage of healing. This creates a systemically catabolic state that directly antagonizes the anabolic processes required for tissue regeneration.

The HPG axis governs the production of sex hormones. Therapies like TRT are direct interventions in this axis. The administration of exogenous testosterone provides a strong anabolic signal but also initiates negative feedback to the hypothalamus and pituitary, reducing the secretion of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH).

The use of agents like Gonadorelin is a sophisticated strategy to counteract this, maintaining some endogenous signaling and testicular function. The relevance to healing is that a stable HPG axis promotes a predictable and balanced hormonal milieu. An unstable axis, or one characterized by supraphysiological androgen levels without commensurate estrogenic balance, can lead to the hyper-inflammatory phenotype at the wound site, mediated by androgen receptor (AR) activation on immune cells.

The healing of an injection site is a complex biological process reflecting the systemic balance between the catabolic signals of the HPA axis and the anabolic signals of the HPG axis.

What Is the Molecular Basis of Hormone-Modulated Healing?

The influence of hormones is ultimately executed at the molecular level through their binding to specific receptors on the cells involved in healing, such as keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and macrophages. The presence and activation of these receptors dictate the cellular response.

Estrogen’s anti-inflammatory and pro-healing effects are mediated by Estrogen Receptors (ER-α and ER-β), which are present on skin cells. When activated, these receptors initiate a signaling cascade that reduces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and alters macrophage behavior, promoting a more efficient phagocytic (cleanup) function with less collateral damage.

Studies have shown that in estrogen-deficient states, such as in ovariectomized animal models or postmenopausal women, the inflammatory response is prolonged and wound closure is delayed. The application of topical estrogen has been shown to reverse this, accelerating healing by restoring this regulatory mechanism.

Androgens, conversely, act through the Androgen Receptor (AR), which is also expressed on key wound-healing cells. The activation of the AR can enhance the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators. The link between androgens and the inhibition of wound healing has been demonstrated in studies where castrated male mice, with low testosterone levels, healed significantly faster than their intact counterparts.

This effect is tied to a reduction in the inflammatory response and more efficient matrix deposition. This highlights that the local hormonal signaling within the wound bed is a critical determinant of the outcome.

Does the Skin Create Its Own Hormones during Healing?

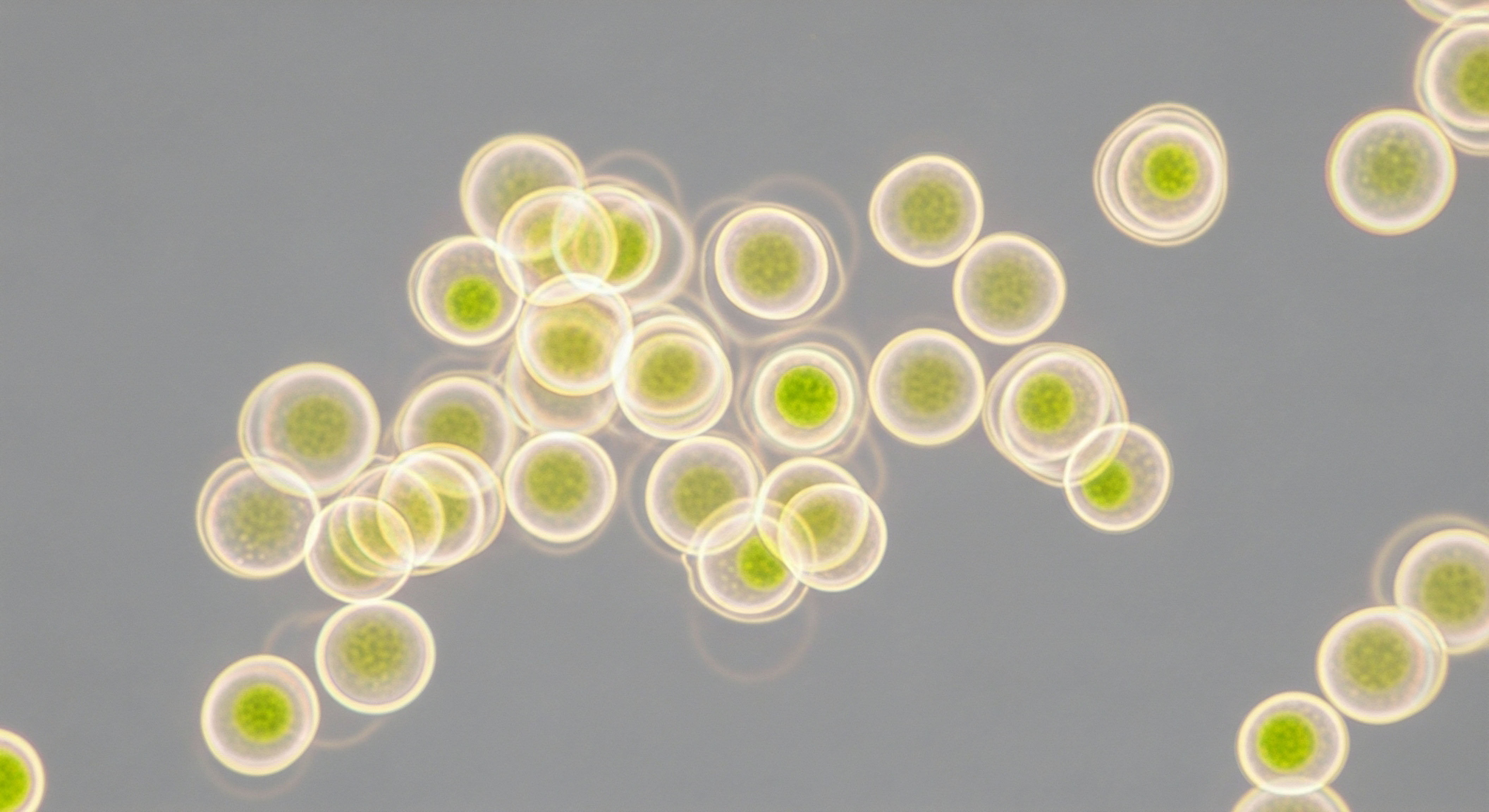

A fascinating area of research is the concept of intracrinology, or local steroidogenesis. The skin is now understood to be a steroidogenic tissue, containing the necessary enzymatic machinery (like cytochrome P450) to synthesize active sex steroids from cholesterol or other precursors.

This means the hormonal environment of the wound is a product of both systemic circulating hormones and those produced locally within the skin itself. This local production can be influenced by the inflammatory state, creating complex feedback loops.

An injury might upregulate certain enzymes, altering the local balance of androgens and estrogens, and thereby influencing the progression of healing independently of systemic levels. This adds a significant layer of complexity to understanding why healing outcomes can vary so much between individuals.

| Hormonal State | Key Molecular Mediators Affected | Resulting Impact on Healing Process |

|---|---|---|

| High Cortisol (HPA Axis Activation) |

Downregulation of procollagen gene expression; suppression of macrophage and lymphocyte function. |

Impaired matrix deposition; delayed inflammatory resolution; increased susceptibility to infection. |

| Low Estrogen (e.g. Menopause) |

Increased expression of TNF-α, IL-6; unchecked neutrophil activity. |

Prolonged and excessive inflammation; delayed onset of the proliferative phase; poor quality of tissue repair. |

| High Testosterone-to-Estrogen Ratio |

Enhanced Smad3 signaling; upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines via Androgen Receptor activation. |

Heightened and sustained inflammatory response; potential for increased proteolytic damage to the wound matrix. |

| High Growth Hormone / IGF-1 |

Upregulation of fibroblast proliferation; increased collagen and protein synthesis. |

Accelerated tissue regeneration; robust proliferative phase; improved tensile strength of the healed tissue. |

- Transforming Growth Factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) A critical cytokine whose expression is modulated by estrogen. It plays a complex role in both promoting fibroblast proliferation and influencing the final quality of scarring.

- Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) A primary pro-inflammatory cytokine. Estrogen’s ability to suppress TNF-α is a key mechanism behind its ability to accelerate healing by reducing excessive inflammation.

- Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) The primary mediator of Growth Hormone’s anabolic effects. Its local availability in the wound bed is essential for driving the cell proliferation required for rebuilding tissue.

- Androgen Receptor (AR) The nuclear receptor through which testosterone and other androgens exert their effects. Its presence and activation on immune cells are directly linked to the enhancement of the inflammatory response.

References

- Ashcroft, G. S. et al. “Androgen-mediated inhibition of wound healing.” Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 104, no. 11, 1999, pp. 1465-1473.

- Ashcroft, G. S. and S. J. Mills. “Androgens and wound healing ∞ more than a male problem.” HMP Global Learning Network, vol. 14, no. 4, 2002.

- Emmerson, E. and M. J. Hardman. “The role of estrogen in skin ageing and wound healing.” Therapeutic Delivery, vol. 3, no. 1, 2012, pp. 5-7.

- Hardman, M. J. and G. S. Ashcroft. “Estrogen, not androgen, is a critical regulator of wound healing in female mice.” Endocrinology, vol. 149, no. 1, 2008, pp. 520-526.

- Herndon, D. N. and R. R. Wolfe. “The role of anabolic hormones for wound healing in catabolic states.” Advances in Wound Care, vol. 12, no. 4, 1999, pp. 178-181.

- Mills, S. J. et al. “Topical oestrogen accelerates cutaneous wound healing in aged humans.” Journal of Investigative Dermatology, vol. 124, no. 3, 2005, pp. 430-438.

- Thornton, M. J. “Estrogens and aging skin.” Dermato-endocrinology, vol. 5, no. 2, 2013, pp. 264-270.

- Gilliver, S. C. et al. “Sex steroids and cutaneous wound healing ∞ the contrasting influences of estrogens and androgens.” Climacteric, vol. 10, no. 4, 2007, pp. 273-280.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a biological grammar for the language your body is speaking through its response to therapy. The tenderness, the bruising, the slow return to normal at an injection site is a personalized data point. It is a signal about the systemic environment in which that local event is taking place. Understanding the science of how your hormones conduct the healing process transforms this observation from a frustrating symptom into a valuable piece of information.

This knowledge is the starting point. It equips you to have a more informed conversation with your clinical team, to look at your own lab results with a new perspective, and to connect the way you feel to the complex, underlying biological mechanisms.

Your personal health journey is one of continually gathering these data points, understanding their meaning, and using them to refine your path toward optimal function and vitality. The goal is to create an internal environment where your body is fully equipped to heal, regenerate, and perform at its peak potential.