Fundamentals

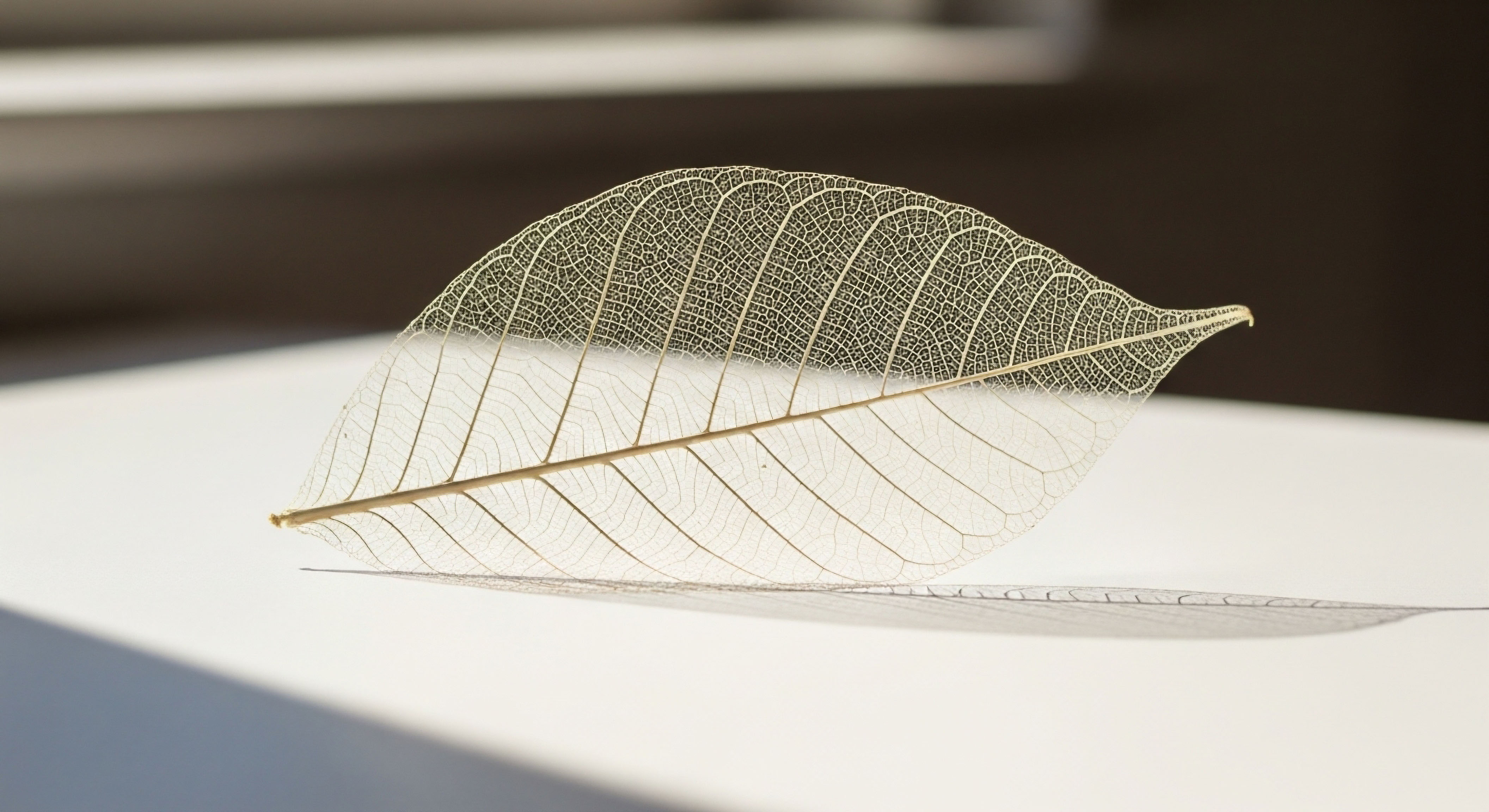

You feel it in your bones, a deep sense of being unrestored, even after a full night in bed. This experience, a persistent fatigue that sleep fails to resolve, is a valid and significant biological signal. It points directly to the quality of your sleep, specifically to the architecture of your nightly rest.

The question of whether hormonal imbalances can directly cause disruptions in deep sleep architecture is answered with a definitive yes. Your endocrine system, the intricate network of glands and hormones that regulate countless bodily functions, is the master conductor of your sleep symphony. When this conductor is out of tune, the most restorative parts of the performance, the deep, slow-wave movements, are the first to falter.

Understanding this connection begins with appreciating what deep sleep, or Slow-Wave Sleep (SWS), truly is. This is the stage of sleep where the brain’s electrical activity slows to large, powerful delta waves. It is a period of profound physical and neurological restoration.

During SWS, the body diligently works to repair muscle tissue, consolidate memories, clear metabolic waste from the brain, and release crucial hormones for growth and repair. When you are deprived of adequate SWS, you are deprived of this fundamental maintenance.

The result is waking up feeling as though you have run a marathon in your sleep, with cognitive fog, physical soreness, and a diminished capacity for the day ahead. This is not a matter of imagination; it is a physiological reality rooted in your body’s internal chemistry.

The architecture of your sleep is a direct reflection of your internal hormonal environment, with deep sleep being particularly vulnerable to imbalances.

The Key Hormonal Players in Sleep Regulation

Your sleep cycle is governed by a precise and delicate dance between several key hormones. These chemical messengers dictate the timing, duration, and quality of your rest. When their production or signaling becomes dysregulated, the entire structure of sleep can collapse, leaving you with fragmented, unrefreshing nights. Recognizing the roles of these hormones is the first step in understanding the root cause of your sleep disruption.

Cortisol the Stress Signal

Cortisol, produced by the adrenal glands, is your body’s primary stress hormone. It follows a natural diurnal rhythm, peaking in the morning to promote wakefulness and gradually declining throughout the day to its lowest point at night, allowing for sleep. Chronic stress disrupts this rhythm, leading to elevated cortisol levels in the evening.

This elevated nighttime cortisol acts as a powerful stimulant, directly interfering with your ability to fall asleep and, more importantly, preventing your brain from entering the deep, restorative stages of SWS. An overactive stress response system, known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, keeps your body in a state of high alert, making deep relaxation and restorative sleep biologically impossible.

Sex Hormones the Architects of Sleep Quality

The reproductive hormones ∞ estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone ∞ play a profound role in shaping sleep architecture. Their influence extends far beyond reproductive health, directly impacting neurotransmitter systems in the brain that regulate sleep.

- Progesterone ∞ This hormone, particularly prominent in the female reproductive cycle, has a known sedative effect. It promotes sleep by stimulating GABA receptors in the brain, the same receptors targeted by many sleep medications. A decline in progesterone, as seen during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle or during perimenopause, removes this calming influence, often leading to difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep.

- Estrogen ∞ Estrogen helps regulate body temperature and supports the function of serotonin and other neurotransmitters involved in sleep. The wild fluctuations and eventual decline of estrogen during perimenopause and menopause are primary drivers of sleep disturbances, including the notorious night sweats that fragment sleep and pull you out of deeper stages.

- Testosterone ∞ In both men and women, testosterone is vital for maintaining healthy sleep patterns. Low levels of testosterone are associated with reduced sleep efficiency, more frequent nighttime awakenings, and a decrease in slow-wave sleep. For men, the age-related decline in testosterone, often termed andropause, is a frequent cause of developing insomnia and poor sleep quality.

Growth Hormone the Restorative Agent

The vast majority of your daily supply of human growth hormone (GH) is released during slow-wave sleep. This is no coincidence; GH is the master agent of physical repair. It stimulates tissue regeneration, muscle growth, and cellular repair throughout the body. A disruption in deep sleep directly curtails the release of GH, creating a detrimental cycle.

Insufficient GH means less physical restoration, which can contribute to feelings of fatigue and body aches. Concurrently, low GH levels themselves can make it harder to achieve deep sleep, further perpetuating the problem.

The lived experience of waking up tired is your body communicating a systemic issue. The architecture of your sleep is not an abstract concept; it is a measurable reflection of your endocrine health. The path to reclaiming restorative sleep begins with understanding and addressing the specific hormonal imbalances that are disrupting its very foundation.

Intermediate

The connection between your hormones and sleep quality moves beyond a simple association. Specific hormonal imbalances create predictable and destructive patterns within your sleep architecture, particularly by eroding the foundation of slow-wave sleep. To truly grasp why you feel so profoundly unrestored, we must examine the precise mechanisms through which these imbalances operate. This is a journey into the body’s internal communication systems, where disrupted signals lead to systemic dysfunction, with your sleep paying the highest price.

The HPA Axis and Cortisol’s Assault on Deep Sleep

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis is the body’s central stress response system. In a well-regulated system, it functions like a precise thermostat, activating in response to a stressor and deactivating once the threat has passed. Chronic physical or psychological stress forces this system into a state of persistent activation. This sustained “on” state results in the continuous production of cortisol, even at night when it should be at its lowest.

Elevated nighttime cortisol directly sabotages deep sleep through several mechanisms:

- Suppression of SWS ∞ Cortisol is a glucocorticoid, a class of hormones that promotes arousal and wakefulness. High levels circulating in the brain at night actively prevent the transition into SWS. Your brain is being told to stay alert and vigilant, making the descent into deep, restorative sleep a physiological impossibility.

- Increased Sleep Fragmentation ∞ The hyperarousal state induced by cortisol leads to more frequent awakenings throughout the night. Even if you do not fully regain consciousness, these micro-arousals are enough to pull you out of deeper sleep stages and reset the sleep cycle, preventing you from accumulating the necessary amount of SWS.

- Altered Sleep Latency ∞ High cortisol can make it difficult to fall asleep in the first place, a condition known as increased sleep onset latency. This shortens the total time available for sleep, further reducing the window for achieving deep sleep stages, which are more prominent in the first half of the night.

This disruption creates a vicious cycle. Poor sleep is itself a significant physiological stressor, which in turn stimulates the HPA axis to produce even more cortisol the following day and night. Your body becomes trapped in a feedback loop of stress and sleeplessness, each condition reinforcing the other.

A dysregulated HPA axis floods the nighttime brain with wakefulness signals, fundamentally blocking the entry into restorative deep sleep.

How Sex Hormone Deficiencies Dismantle Sleep Architecture

The decline of sex hormones during perimenopause, menopause, and andropause is a primary cause of age-related sleep deterioration. These hormones are not merely for reproduction; they are integral modulators of brain function and sleep regulation. Their absence leaves the brain vulnerable to disruption.

The Female Hormonal Transition

For women, the transition into menopause represents a period of profound hormonal chaos that directly impacts sleep architecture. The mechanisms are distinct yet compounding.

Progesterone’s Protective Role Diminished

Progesterone’s sleep-promoting effects are potent. It functions as a positive allosteric modulator of the GABA-A receptor, meaning it enhances the calming effect of the brain’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, GABA. This action is similar to that of benzodiazepines and other sedative hypnotics. As progesterone levels fall precipitously during perimenopause, the brain loses a key source of natural calming and sedative input, leading to a state of relative neural excitation that is incompatible with deep sleep.

Estrogen’s Stabilizing Influence Lost

Estrogen’s role is more complex, involving temperature regulation and neurotransmitter balance. The vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes and night sweats) triggered by estrogen withdrawal are a major source of sleep fragmentation. An episode can raise heart rate and body temperature, causing an abrupt awakening that shatters sleep continuity. Beyond this, estrogen helps maintain healthy levels of serotonin and acetylcholine, neurotransmitters critical for progressing through the sleep stages smoothly. Fluctuating estrogen disrupts these systems, contributing to a disorganized and shallow sleep architecture.

The Male Hormonal Decline

In men, the gradual decline of testosterone associated with andropause contributes significantly to poor sleep. Studies have shown a direct correlation between low testosterone levels and reduced SWS. While the exact mechanisms are still being fully elucidated, testosterone appears to influence the neurotransmitter systems that support deep sleep.

Furthermore, low testosterone is a known risk factor for the development of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), a condition where breathing repeatedly stops and starts during sleep. These apneic events cause frequent arousals and severe oxygen desaturation, which completely prevents the brain from sustaining deep sleep.

The following table outlines the symptoms associated with hormonal decline and their direct impact on sleep.

| Hormone | Common Symptoms of Deficiency | Direct Impact on Sleep Architecture |

|---|---|---|

| Progesterone (Women) | Anxiety, irritability, difficulty falling asleep | Reduced GABAergic tone, leading to hyperarousal and suppression of SWS. |

| Estrogen (Women) | Hot flashes, night sweats, mood swings | Sleep fragmentation from vasomotor symptoms; disruption of neurotransmitter balance. |

| Testosterone (Men & Women) | Fatigue, low libido, reduced muscle mass, cognitive fog | Decreased SWS, increased nighttime awakenings, increased risk of sleep apnea. |

Restoring Deep Sleep through Hormonal and Peptide Protocols

Understanding these mechanisms opens the door to targeted interventions. The goal of these protocols is to correct the underlying hormonal deficit, thereby allowing the body’s natural sleep-regulating systems to function correctly. These are not sleep aids in the traditional sense; they are foundational repairs to your endocrine system.

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT)

For individuals with clinically diagnosed deficiencies, hormonal optimization is the most direct path to restoring sleep. The protocols are tailored to the specific needs of men and women.

- For Women ∞ A combination of bioidentical progesterone and estrogen is often used. Progesterone, taken orally before bed, can immediately improve sleep onset and depth due to its sedative properties. Estrogen replacement helps stabilize body temperature, reducing night sweats and their associated arousals. In some cases, a low dose of testosterone is added to address deficiencies that contribute to fatigue and poor sleep quality.

- For Men ∞ Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) aims to restore testosterone levels to a healthy, youthful range. A standard protocol might involve weekly injections of Testosterone Cypionate. This can lead to significant improvements in sleep quality, including an increase in SWS and a reduction in nighttime awakenings. Supporting medications like Anastrozole may be used to control the conversion of testosterone to estrogen, while Gonadorelin helps maintain the body’s own hormonal signaling pathways.

Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy

For individuals whose primary complaint is non-restorative sleep and physical fatigue, Growth Hormone (GH) peptide therapy presents a powerful and targeted solution. Since the majority of GH is released during SWS, and GH itself promotes SWS, a deficiency creates a difficult cycle to break. Peptides are small proteins that signal the body to produce its own GH.

A leading protocol combines CJC-1295 and Ipamorelin. These peptides work synergistically:

- CJC-1295 ∞ This is a Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH) analogue. It signals the pituitary gland to release GH in a slow, steady pulse, mimicking the body’s natural rhythm.

- Ipamorelin ∞ This is a Growth Hormone Secretagogue (GHS) and a ghrelin mimetic. It stimulates the pituitary through a different pathway and also helps suppress somatostatin, a hormone that inhibits GH release. This dual action results in a strong, clean pulse of GH.

By stimulating a significant, naturalistic release of GH shortly after administration, this peptide combination directly promotes the onset and duration of SWS. Users often report a dramatic improvement in sleep depth, a reduction in awakenings, and a profound sense of physical restoration upon waking. This approach does not force sleep like a sedative; it restores a key physiological process that is fundamental to deep sleep itself.

Academic

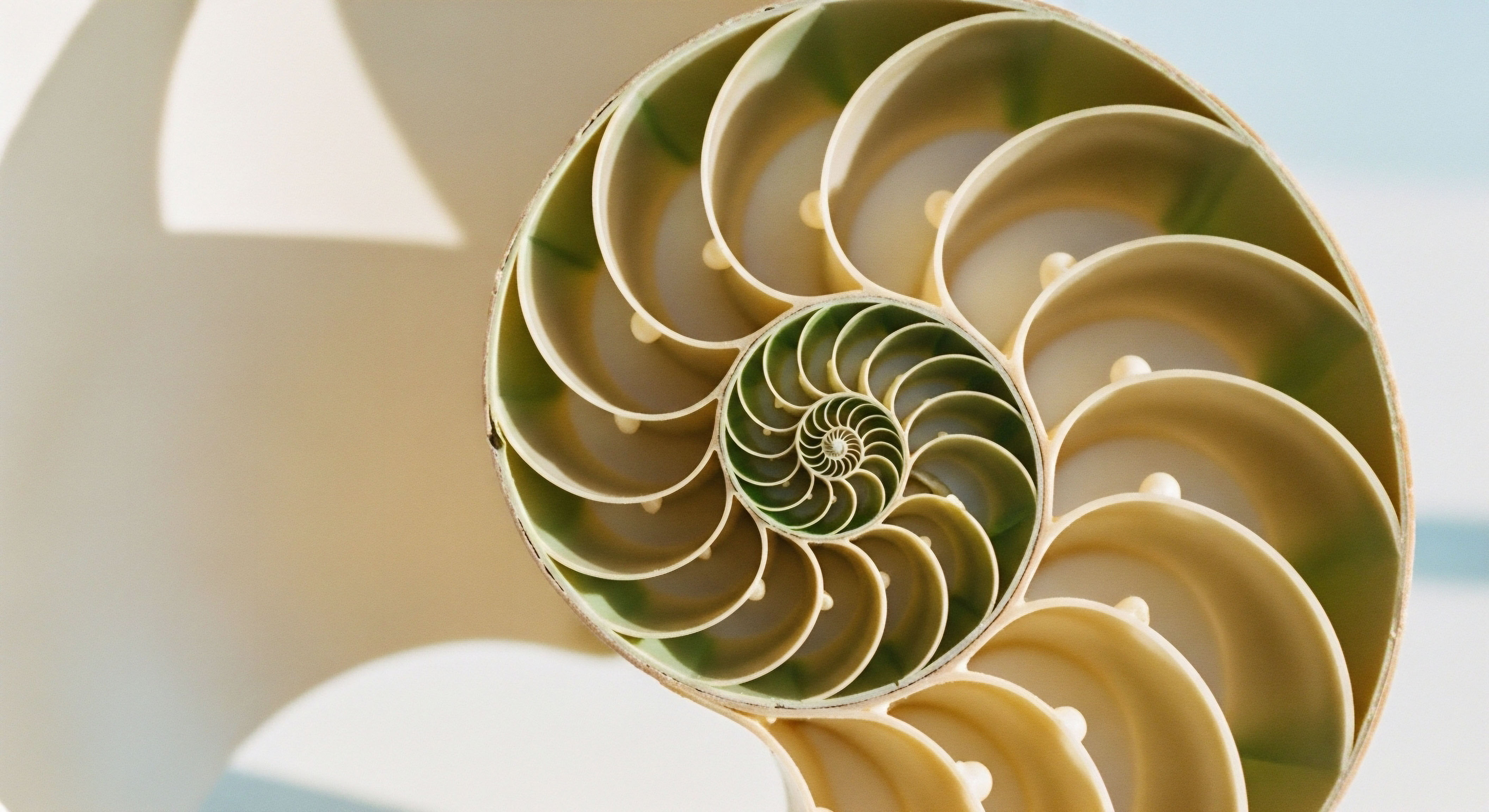

A sophisticated analysis of hormonal influence on sleep architecture requires a systems-biology perspective, moving beyond the action of a single hormone to appreciate the deeply intertwined nature of the body’s major neuroendocrine axes. The deterioration of deep, slow-wave sleep (SWS) is rarely the result of a single hormonal failure.

It is the predictable outcome of crosstalk and feedback loop dysregulation between the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, and the Growth Hormone (GH) axis. Understanding this integrated network provides a more complete and clinically relevant picture of why restorative sleep collapses under endocrine stress.

The Interplay of the HPA and HPG Axes

The HPA and HPG axes exist in a state of reciprocal inhibition. This is a biologically conserved mechanism designed to prioritize survival over reproduction during times of high stress. The activation of the HPA axis, initiated by the release of Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus, leads to the downstream release of cortisol. Chronically elevated CRH and cortisol exert a powerful suppressive effect on the HPG axis at multiple levels.

Specifically, CRH can directly inhibit the release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus. Cortisol can further suppress the HPG axis by reducing the pituitary’s sensitivity to GnRH and by impairing gonadal function directly. The result is a state of stress-induced hypogonadism.

This biological reality explains why chronic stress can lead to menstrual irregularities in women and suppressed testosterone levels in men. The physiological consequence for sleep is a dual assault ∞ the hyperarousal driven by the overactive HPA axis is compounded by the loss of the sleep-promoting and stabilizing effects of the gonadal hormones. The brain is simultaneously flooded with “wake up” signals (cortisol) while being deprived of “calm down” signals (progesterone, testosterone).

What Are the Neurochemical Mechanisms of Sleep Disruption?

The neurochemical underpinnings of this disruption are centered on the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission. Cortisol enhances the function of the glutamatergic system, the brain’s primary excitatory pathway, promoting a state of neuronal excitability and vigilance. Conversely, key sleep-promoting hormones exert a calming influence.

Progesterone’s primary sleep-modulating effect is its conversion to the neurosteroid allopregnanolone, a potent positive allosteric modulator of the GABA-A receptor. This enhances chloride ion influx into neurons, leading to hyperpolarization and reduced neuronal excitability, which is a prerequisite for SWS onset. The decline in progesterone during perimenopause removes this powerful GABAergic brake, leaving the brain’s excitatory systems, already potentiated by cortisol, largely unopposed.

The reciprocal inhibition between the stress and reproductive axes creates a feedback loop where chronic stress suppresses sex hormones, and low sex hormones amplify the stress response, leading to a collapse of deep sleep.

The Growth Hormone Axis the Final Piece of the Puzzle

The regulation of the GH axis is intricately linked to both sleep and the HPA axis. The release of GH from the pituitary is stimulated by Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH) and inhibited by somatostatin. GHRH is not just a secretagogue; it is also a powerful somnogen, a substance that directly promotes sleep, particularly SWS. The highest levels of GHRH secretion occur during the first few hours of sleep, driving the large pulse of GH that characterizes this period.

The HPA axis directly antagonizes this system. CRH and cortisol both stimulate the release of somatostatin, which in turn inhibits the release of GHRH and GH. Therefore, a chronically activated HPA axis not only disrupts sleep through its own hyperarousing effects but also by actively suppressing the very neurochemical pathway that promotes deep sleep and physical restoration.

This creates a devastating feed-forward cycle ∞ high cortisol suppresses GHRH and SWS, the lack of SWS prevents the main pulse of GH release, and the resulting low GH levels fail to provide the restorative signaling the body needs, contributing to daytime fatigue and further stress.

How Do Growth Hormone Peptides Restore SWS?

This is where the clinical application of peptide therapies becomes particularly insightful. Growth hormone secretagogues, such as the combination of CJC-1295 and Ipamorelin, effectively bypass the HPA-induced suppression of the GH axis.

The table below details the mechanisms of action for key peptides used in sleep restoration protocols.

| Peptide | Mechanism of Action | Effect on Sleep Architecture |

|---|---|---|

| Sermorelin | A GHRH analogue that directly stimulates the GHRH receptor on the pituitary. | Increases the amplitude and frequency of GH pulses, promoting SWS. Its short half-life mimics natural GHRH release. |

| CJC-1295 | A longer-acting GHRH analogue that provides a sustained increase in baseline GH levels, creating a continuous “bleed” of GH. | Enhances overall GH production and has been shown to increase SWS and improve sleep quality. |

| Ipamorelin | A ghrelin mimetic that stimulates the GH secretagogue receptor (GHSR) on the pituitary. It also suppresses somatostatin. | Induces a strong, clean pulse of GH without significantly affecting cortisol or prolactin. Its action on the ghrelin receptor may have independent sleep-modulating effects. |

| Tesamorelin | A highly stable GHRH analogue, primarily studied for its effects on visceral adipose tissue. | As a potent GHRH agonist, it effectively increases IGF-1 and has a positive impact on SWS depth and continuity. |

The combination of CJC-1295 and Ipamorelin is particularly effective because it targets the GH axis through two distinct and synergistic pathways. CJC-1295 provides a steady, elevated baseline of GHRH signaling, while Ipamorelin induces a powerful, pulsatile release of GH. This dual stimulation can override the inhibitory tone of somatostatin that is elevated due to HPA axis hyperactivity.

By restoring the nocturnal GH pulse, these peptides do more than just increase GH levels; they reinstate a fundamental biological rhythm that is inextricably linked to the generation of slow-wave sleep. The clinical result is not just better sleep, but a restoration of the very architecture of restorative sleep, leading to improvements in physical recovery, cognitive function, and overall metabolic health.

References

- Weikel, J. C. et al. “Ghrelin promotes slow-wave sleep in humans.” American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 284, no. 2, 2003, pp. E407-E415.

- Buckley, T. M. and A. W. Schatzberg. “On the interactions of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and sleep ∞ normal HPA axis activity and circadian rhythm, exemplary sleep disorders.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 90, no. 5, 2005, pp. 3106-3114.

- Steiger, A. “Neurochemical regulation of sleep.” Journal of Psychiatric Research, vol. 41, no. 7, 2007, pp. 537-552.

- Caufriez, A. et al. “Progesterone and sleep in postmenopausal women.” Hormone and Metabolic Research, vol. 43, no. 6, 2011, pp. 424-430.

- Wittert, G. “The relationship between sleep disorders and testosterone in men.” Asian Journal of Andrology, vol. 16, no. 2, 2014, pp. 262-265.

- Brandenberger, G. and M. Follenius. “Growth hormone secretion during sleep ∞ a review.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, vol. 2, no. 1, 1998, pp. 29-39.

- Joffe, H. et al. “Adverse effects of induced hot flashes on objectively recorded and subjectively reported sleep ∞ results of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist experimental protocol.” Menopause, vol. 20, no. 9, 2013, pp. 905 ∞ 914.

- Vgontzas, A. N. et al. “Insomnia with objective short sleep duration ∞ the most biologically severe phenotype of the disorder.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, vol. 17, no. 4, 2013, pp. 241-254.

- Perras, B. et al. “The effects of growth hormone-releasing peptide-2 (GHRP-2) on sleep, sleep-related hormone secretion and vigilance in man.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 84, no. 1, 1999, pp. 320-325.

- Schüssler, P. et al. “Progesterone and its metabolite allopregnanolone in women with sleep disorders.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 33, no. 8, 2008, pp. 1124-1131.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Path to Restoration

The information presented here offers a biological map, connecting the symptoms you feel to the intricate systems within your body. You have seen how the silent language of hormones speaks directly to the quality of your nightly rest, and how an imbalance in this language can leave you feeling perpetually unrestored. This knowledge is the foundational step. It moves the conversation from one of vague fatigue to one of specific, measurable, and addressable physiological processes.

Your personal health narrative is unique. The specific interplay of your genetics, your life stressors, and your hormonal trajectory has created the precise situation you find yourself in today. The path forward, therefore, involves looking at this map and identifying your own location.

It requires a thoughtful consideration of your own experiences in the context of this clinical science. Are the disruptions you feel aligned more with the patterns of HPA axis dysregulation, or do they resonate more with the timeline of a natural hormonal transition like menopause or andropause?

This self-reflection is not about self-diagnosis. It is about becoming an informed and empowered participant in your own wellness journey. The science provides the “what” and the “how,” but you hold the invaluable data of your own lived experience. The ultimate goal is to integrate these two powerful sources of information.

By understanding the potential root causes of your unrestored sleep, you are now equipped to ask more precise questions and seek out guidance that is tailored not just to a symptom, but to the underlying system. This is the beginning of a proactive partnership with your own biology, a journey toward reclaiming the profound and essential power of deep, restorative sleep.