Fundamentals

You feel it long before you can name it. A persistent hum of exhaustion that sleep does not touch. A subtle fogginess that clouds your thinking. A sense of being perpetually wired and tired, running on a fuel that feels thin and insufficient.

This experience, this lived reality for so many, is the starting point of our conversation. Your body is communicating a profound truth through the language of symptoms. The question of whether hormonal imbalances from chronic stress can be reversed begins with acknowledging the validity of this experience.

The answer is deeply rooted in the biology of how your body manages energy and perceives threat. Reclaiming your vitality is a process of recalibrating the body’s internal communication systems, moving them from a state of high alert to one of sustainable function.

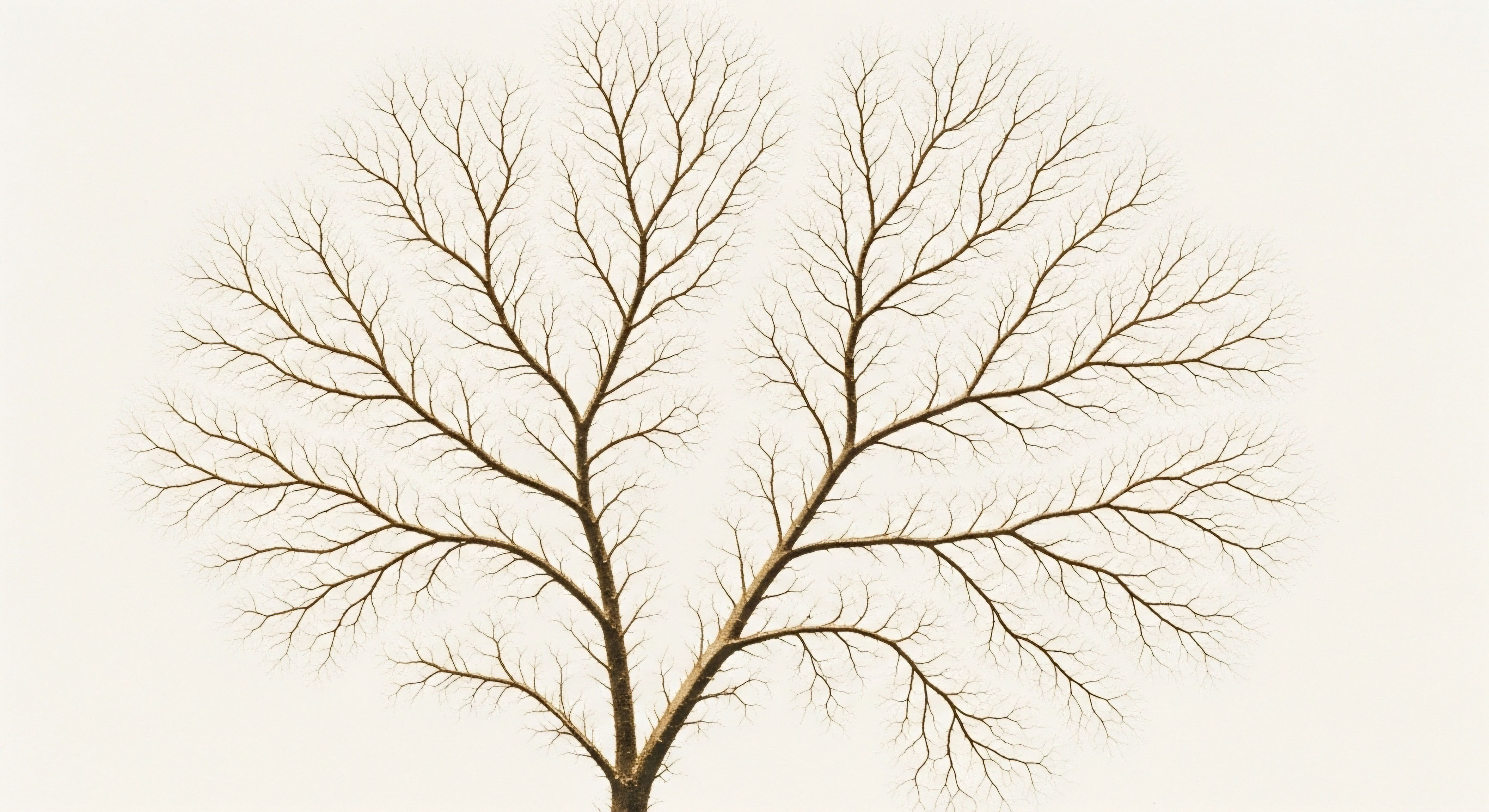

At the center of this biological narrative is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. This is the body’s primary stress response system, a sophisticated network connecting key areas of your brain to your adrenal glands, which sit atop your kidneys.

When your brain perceives a stressor, be it a physical danger, a demanding job, or persistent emotional distress, the hypothalamus releases Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH). This signals the pituitary gland to secrete Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH). ACTH then travels through the bloodstream to the adrenal glands, instructing them to produce cortisol.

In short bursts, cortisol is life-sustaining. It liberates glucose for energy, sharpens focus, and modulates inflammation, preparing you to handle an immediate challenge. After the event, a negative feedback loop engages, and cortisol levels recede. Chronic stress disrupts this elegant design. The “off-switch” becomes less effective, leading to persistently elevated cortisol levels that send ripples of dysfunction throughout your entire physiology.

Understanding the HPA axis is the first step in comprehending how the abstract feeling of stress translates into concrete biological consequences.

The Central Role of Cortisol

Cortisol is often called the “stress hormone,” yet its functions are vast and essential for life. It is a glucocorticoid hormone synthesized in the adrenal cortex from cholesterol. Its primary role is to ensure the brain has an adequate energy supply during times of stress.

It achieves this by promoting gluconeogenesis, the creation of glucose from non-carbohydrate sources in the liver. Simultaneously, it limits insulin’s effect to prevent other tissues from taking up this precious glucose, preserving it for the central nervous system. This is a brilliant short-term survival strategy.

When this state becomes chronic, the consequences are significant. Persistently high cortisol can lead to increased blood sugar levels and insulin resistance, a condition where the body’s cells no longer respond efficiently to insulin’s signals. This is a direct pathway to metabolic disruption, weight gain, and systemic inflammation.

The influence of cortisol extends deep into the body’s other critical systems. It directly impacts the immune system, initially acting as an anti-inflammatory agent but eventually, with chronic exposure, contributing to immune dysregulation and a heightened state of inflammation. It affects bone density, digestive function, and cardiovascular health.

High levels of cortisol can constrict blood vessels and increase blood pressure, placing a continuous strain on the heart and circulatory system. This is how a state of mental and emotional pressure becomes a physical reality, written into the very fabric of your cells and organ systems.

How Stress Impacts Other Hormonal Systems

The body’s hormonal systems are deeply interconnected. The HPA axis does not operate in isolation. Its constant activation has profound downstream effects on the networks that govern reproduction, metabolism, and growth. Two key systems are particularly vulnerable to the influence of chronic stress.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) Axis

The HPG axis controls reproductive function and the production of sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen. In a state of chronic stress, the body’s survival-oriented programming makes a critical resource allocation decision. It perceives the environment as unsafe for procreation and diverts resources away from the HPG axis.

Elevated cortisol levels can suppress the release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus. This, in turn, reduces the pituitary’s output of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). For men, reduced LH means the testes receive a weaker signal to produce testosterone.

For women, disruptions in the precise, cyclical release of these hormones can lead to irregular menstrual cycles, changes in estrogen and progesterone levels, and exacerbated symptoms of perimenopause. This is a direct biological link between feeling overwhelmed and experiencing symptoms like low libido, fatigue, and mood changes.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) Axis

The HPT axis regulates your metabolism by controlling the production of thyroid hormones. These hormones, primarily thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), set the metabolic rate of every cell in your body. Chronic stress can interfere with this system in several ways. High cortisol levels can inhibit the production of Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) from the pituitary.

Perhaps more significantly, it can impair the conversion of the less active T4 hormone into the more potent T3 hormone in peripheral tissues. This can lead to a state of functional hypothyroidism, where TSH and T4 levels on a lab report might appear within the standard range, yet the individual experiences all the symptoms of an underactive thyroid ∞ fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, and brain fog. The body, in an effort to conserve energy for the perceived crisis, effectively turns down its metabolic thermostat.

Reversing these imbalances is possible because these pathways are designed to be adaptive. By systematically removing the chronic stress signal and providing the body with the resources it needs to repair and recalibrate, these systems can be guided back toward their intended state of balance. This process involves a combination of targeted lifestyle modifications and, when necessary, specific clinical protocols designed to support the body’s return to optimal function.

Intermediate

The journey from recognizing the symptoms of stress-induced hormonal imbalance to actively reversing them requires a more granular understanding of the clinical interventions available. This is where we translate foundational knowledge into a practical framework for recovery.

The core principle is twofold ∞ first, to mitigate the chronic activation of the HPA axis, and second, to directly support the hormonal systems that have been compromised. This involves a sophisticated interplay of lifestyle adjustments, nutritional strategies, and targeted therapeutic protocols. Success is predicated on viewing the body as an integrated system, where signaling safety through one pathway can create positive cascades throughout the entire network.

Assessing the Damage through Clinical Markers

Before initiating any protocol, a precise diagnosis is essential. This moves beyond subjective symptoms and into the realm of objective data. A comprehensive blood panel is the cornerstone of this process, providing a snapshot of your internal hormonal environment. It allows for the identification of specific imbalances and the creation of a personalized therapeutic strategy.

- HPA Axis Markers ∞ A diurnal cortisol test, often performed using saliva or dried urine samples, is invaluable. It measures cortisol levels at four key points throughout the day, revealing the rhythm of your stress response system. A healthy pattern shows a peak in the morning (the Cortisol Awakening Response) followed by a gradual decline throughout the day. A dysfunctional pattern might show elevated levels at night, a blunted morning peak, or a flat curve, each indicating a different stage of HPA axis dysregulation. Measuring DHEA-S (dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate), an adrenal hormone that can buffer some of cortisol’s effects, is also critical. The cortisol-to-DHEA ratio provides insight into the balance between catabolic (breakdown) and anabolic (build-up) processes in the body.

- HPG Axis Markers ∞ For men, this includes Total and Free Testosterone, Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG), Luteinizing Hormone (LH), and Estradiol. High stress can suppress LH, leading to low testosterone production. It can also increase SHBG, which binds to testosterone, reducing the amount of free, bioavailable hormone. For women, the assessment is more complex and depends on menstrual status. Key markers include Estradiol, Progesterone, LH, FSH, and Testosterone. The timing of the blood draw is critical and must be coordinated with the menstrual cycle for pre-menopausal women.

- HPT Axis Markers ∞ A standard TSH test is insufficient. A comprehensive thyroid panel should include TSH, Free T4, Free T3, and Reverse T3 (rT3). Chronic stress can increase the conversion of T4 into the inactive rT3, effectively blocking thyroid hormone action at the cellular level. Measuring thyroid antibodies (TPO and TG) is also important to screen for autoimmune thyroid conditions, which can be exacerbated by stress.

- Metabolic Markers ∞ Given cortisol’s impact on blood sugar, assessing Fasting Insulin, Fasting Glucose, and HbA1c is non-negotiable. These markers provide a clear picture of your insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic health.

Strategic Lifestyle Interventions the Foundation of Reversal

No clinical protocol can succeed without first addressing the root cause of the HPA axis activation. Lifestyle modifications are not supplementary; they are the primary treatment. Their purpose is to send consistent signals of safety and stability to the nervous system, allowing the HPA axis to downregulate.

Systematic lifestyle changes form the therapeutic foundation upon which all other hormonal interventions are built.

| Intervention | Mechanism of Action | Targeted Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Morning Sunlight Exposure |

Entrains the circadian rhythm by signaling the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus. This helps anchor the daily cortisol cycle, promoting a robust morning peak and subsequent decline. |

Normalization of the diurnal cortisol curve; improved sleep-wake cycles. |

| Protein-Focused Breakfast |

Stabilizes blood glucose levels early in the day, preventing mid-morning energy crashes and reducing the need for cortisol spikes to manage blood sugar. Provides amino acids necessary for neurotransmitter synthesis. |

Improved energy stability; reduced cravings; support for mood regulation. |

| Zone 2 Cardio |

Low-intensity, steady-state exercise improves mitochondrial efficiency and insulin sensitivity without significantly raising cortisol levels. It enhances the body’s ability to use fat for fuel. |

Lowered fasting insulin; improved metabolic flexibility; enhanced stress resilience. |

| Mindfulness or Meditation |

Activates the parasympathetic nervous system (“rest and digest”) and reduces activity in the amygdala, the brain’s threat detection center. This directly counteracts the “fight or flight” response. |

Reduced perceived stress; lower resting heart rate and blood pressure; decreased cortisol output. |

| Consistent Sleep Schedule |

Sleep is when the body undertakes critical repair processes and hormonal regulation. A consistent schedule reinforces the circadian rhythm, facilitating the natural overnight drop in cortisol and rise in growth hormone. |

Restoration of HPA axis feedback sensitivity; improved cellular repair; enhanced cognitive function. |

Clinical Protocols for Hormonal Recalibration

When lifestyle interventions are insufficient to fully restore balance, or when deficiencies are severe, targeted clinical protocols can be used to support the body’s recovery. These are not a replacement for foundational work but act as a powerful tool to accelerate the return to optimal function.

Supporting the HPG Axis Testosterone Optimization

For men with clinically low testosterone secondary to chronic stress, Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) can be a transformative intervention. The goal is to restore testosterone levels to an optimal physiological range, which in turn can improve energy, mood, cognitive function, and metabolic health, creating a positive feedback loop that enhances stress resilience.

A standard protocol often involves:

- Testosterone Cypionate ∞ Typically administered as a weekly intramuscular or subcutaneous injection. This provides a stable level of testosterone in the body, avoiding the daily fluctuations of gels or creams.

- Gonadorelin ∞ This is a GnRH analogue. Administered via subcutaneous injection, it mimics the body’s natural signal from the hypothalamus, stimulating the pituitary to produce LH and FSH. This preserves testicular function and fertility, preventing the testicular atrophy that can occur with testosterone-only therapy.

- Anastrozole ∞ An aromatase inhibitor. Testosterone can be converted into estrogen via the aromatase enzyme. In some men, this conversion can be excessive, leading to side effects. Anastrozole is used judiciously to block this process and maintain a healthy testosterone-to-estrogen ratio.

For women, particularly those in the peri- and post-menopausal stages where stress can severely exacerbate symptoms, hormonal support is also critical. This may involve low-dose subcutaneous testosterone injections to address low libido, fatigue, and cognitive complaints. Progesterone, which has a calming effect on the nervous system and is often depleted by stress, can be prescribed to improve sleep and mood. The approach is always personalized, based on symptoms and comprehensive lab testing.

Peptide Therapy a Targeted Approach to Repair and Growth

Peptide therapies represent a more nuanced approach to hormonal optimization. These are short chains of amino acids that act as signaling molecules, instructing the body to perform specific functions. They can be particularly effective for addressing the consequences of chronic stress.

Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy is a key example. Chronic stress and high cortisol levels suppress the natural production of Growth Hormone (GH), which is critical for cellular repair, muscle maintenance, and metabolic health. Instead of directly injecting GH, peptides are used to stimulate the body’s own production.

- Ipamorelin / CJC-1295 ∞ This is a popular combination. CJC-1295 is a Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH) analogue, which signals the pituitary to release GH. Ipamorelin is a ghrelin mimetic and a Growth Hormone Secretagogue (GHS), which amplifies the release pulse and also reduces the production of somatostatin, a hormone that inhibits GH release. This combination provides a strong, naturalistic pulse of GH, primarily during sleep, which supports tissue repair, improves sleep quality, and can aid in fat loss.

- Sermorelin ∞ Another GHRH analogue that helps restore the natural pulsatile release of GH from the pituitary gland.

By using these targeted protocols in conjunction with foundational lifestyle changes, it is possible to systematically reverse the multifaceted impacts of chronic stress. The process is one of removing the signals of danger while actively providing the biochemical support needed for the body to rebuild and restore its own elegant, self-regulating systems.

Academic

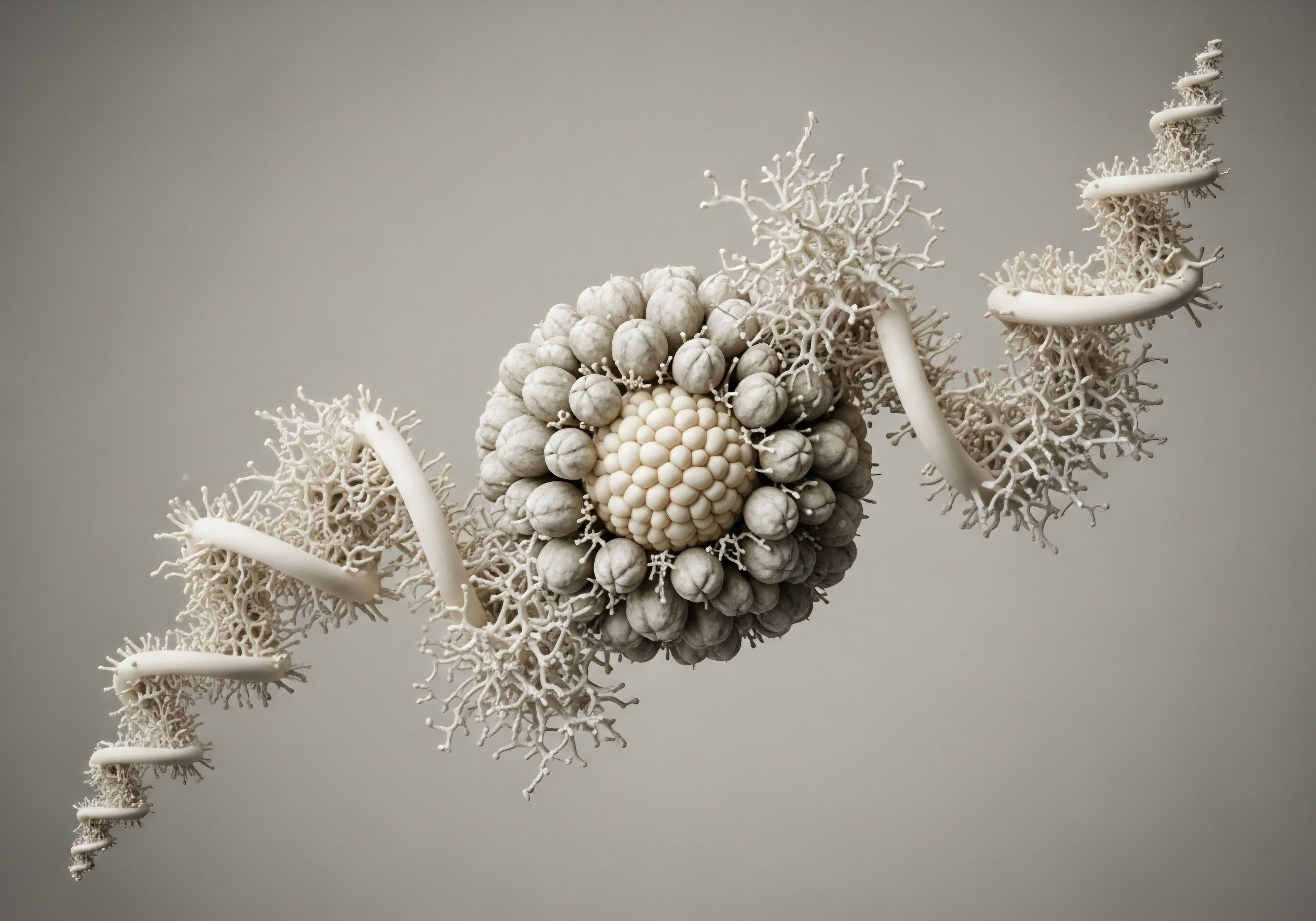

A sophisticated analysis of stress-induced hormonal dysregulation requires moving beyond the description of axis disruption and into the deeper biochemical and cellular mechanisms that underpin these changes. One of the most compelling models for understanding the systemic resource drain of chronic stress is the “Pregnenolone Steal” hypothesis.

This concept provides a biochemical framework for how the perpetual demand for cortisol production directly limits the substrate available for the synthesis of other vital steroid hormones, including DHEA and the sex hormones. Examining this pathway reveals the profound interconnectedness of the adrenal and gonadal systems at a molecular level.

The Steroidogenic Pathway a Shared Origin

All steroid hormones, including cortisol, DHEA, testosterone, and estrogen, are synthesized from a common precursor molecule ∞ cholesterol. The conversion of cholesterol into pregnenolone is the rate-limiting step in this entire process, occurring within the mitochondria and catalyzed by the enzyme CYP11A1. Pregnenolone sits at a critical metabolic crossroads. From this point, it can be directed down one of two primary pathways within the adrenal gland:

- The Glucocorticoid Pathway ∞ Pregnenolone is converted to progesterone by the enzyme 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD). Progesterone is then hydroxylated by CYP17A1 and subsequently by CYP21A2 and CYP11B1 to ultimately produce cortisol. This is the pathway that is chronically upregulated in response to persistent stress signals (ACTH stimulation).

- The Androgen Pathway ∞ Pregnenolone is hydroxylated by the 17α-hydroxylase activity of the enzyme CYP17A1, and then its C17-20 bond is cleaved by the 17,20-lyase activity of the same enzyme to form dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). DHEA is the primary precursor for the synthesis of androgens and estrogens.

What Is the Pregnenolone Steal Hypothesis?

The “Pregnenolone Steal” hypothesis posits that under conditions of chronic HPA axis activation, the enzymatic machinery of the adrenal cortex is overwhelmingly biased towards the production of cortisol. The constant, high-level stimulation by ACTH leads to an upregulation of the enzymes in the glucocorticoid pathway.

This creates a powerful metabolic pull, shunting available pregnenolone substrate preferentially towards progesterone and then cortisol. This preferential direction of substrate comes at the expense of the androgen pathway. With a finite pool of pregnenolone available, its diversion to cortisol synthesis results in a relative deficiency in the substrate needed to produce DHEA. This is not a literal “theft” of a molecule, but rather a profound shift in enzymatic priority driven by a sustained survival signal.

The consequences of this shift are systemic. A decline in DHEA levels is a well-documented biomarker of chronic stress and aging. DHEA and its sulfated form, DHEA-S, have important biological functions, including neuroprotective effects, immune modulation, and anti-glucocorticoid actions that can buffer the negative impacts of cortisol.

A lowered DHEA-to-cortisol ratio is a potent indicator of an imbalanced, catabolic state. Furthermore, since DHEA is the precursor to sex hormones, this shunting mechanism provides a direct biochemical link between chronic stress and the low testosterone and estrogen-related symptoms seen clinically.

The Pregnenolone Steal hypothesis offers a molecular explanation for how the body’s survival imperative can deplete the resources needed for repair and reproduction.

Glucocorticoid Receptor Resistance a Downstream Consequence

The plot thickens at the level of the target tissues. One might assume that chronically elevated cortisol would lead to a state of amplified glucocorticoid effects throughout the body. The reality is more complex and involves a phenomenon known as glucocorticoid receptor (GR) resistance.

In a healthy system, cortisol binds to glucocorticoid receptors inside the cell, and this hormone-receptor complex translocates to the nucleus to regulate gene expression. This same mechanism is responsible for the negative feedback signal to the hypothalamus and pituitary, telling them to stop producing CRH and ACTH.

Under the strain of chronic stress, several things can happen. The sheer volume of cortisol can lead to a downregulation in the number of glucocorticoid receptors on cell surfaces. The inflammatory cytokines that often accompany chronic stress (like IL-6 and TNF-alpha) can also interfere with the signaling cascade, impairing the ability of the GR to translocate to the nucleus or bind to DNA effectively.

This creates a paradoxical and damaging state. The central feedback mechanisms in the brain become resistant to cortisol’s “off” signal, so the HPA axis continues to pump out more cortisol. Simultaneously, peripheral tissues like immune cells and metabolic tissues also become resistant, meaning that ever-higher levels of cortisol are needed to achieve the same physiological effect.

This leads to a vicious cycle of escalating cortisol levels coexisting with widespread inflammation and metabolic dysfunction, as the tissues that should be responding to cortisol’s regulatory signals become “deaf” to its message.

| System Axis | Primary Hormones Affected | Key Clinical Symptoms | Underlying Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPA Axis |

Cortisol, DHEA |

Fatigue, anxiety, insomnia, brain fog, sugar cravings, poor immune function. |

Loss of negative feedback sensitivity, leading to diurnal rhythm disruption and glucocorticoid receptor resistance. |

| HPG Axis (Male) |

Testosterone, LH |

Low libido, erectile dysfunction, loss of muscle mass, depression, reduced motivation. |

Cortisol-mediated suppression of GnRH at the hypothalamus, leading to reduced LH signaling to the testes. |

| HPG Axis (Female) |

Estrogen, Progesterone |

Irregular menstrual cycles, worsened PMS, infertility, hot flashes, mood swings. |

Disruption of pulsatile GnRH release, altering the LH/FSH ratio and impairing ovulation and progesterone production. |

| HPT Axis |

T3, T4, TSH |

Persistent fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, hair loss, constipation. |

Cortisol-mediated inhibition of TSH and impaired peripheral conversion of inactive T4 to active T3. |

Are Clinical Interventions Supported by This Model?

This deep dive into the biochemical pathways validates the multi-pronged approach to treatment. Lifestyle interventions that reduce the primary stress signal are paramount because they are the only way to lessen the ACTH-driven demand for cortisol, thereby relieving the pressure on the pregnenolone pathway.

Nutritional support with B vitamins and vitamin C, which are cofactors in adrenal hormone synthesis, becomes critical to support adrenal function. The use of “adaptogens” like Ashwagandha or Rhodiola can be understood as agents that may help modulate the stress response at the level of the HPA axis, potentially improving GR sensitivity.

When it comes to hormonal therapies, this model provides a clear rationale. TRT for a man with stress-induced hypogonadism is not just masking a symptom; it is replenishing a specific downstream product that has been depleted due to the upstream “steal.” The use of DHEA as a supplement in some cases can be seen as an attempt to directly backfill the depleted androgen precursor pool.

Peptide therapies that stimulate GH release work to counteract the catabolic state fostered by the high cortisol-to-DHEA ratio, promoting an anabolic, repair-oriented environment. The reversal of stress-induced hormonal imbalance is, therefore, a process of intervening at multiple points in this complex web ∞ reducing the initial signal, supporting the overwhelmed enzymatic pathways, and replenishing the specific molecules that have been depleted by the body’s sustained, and ultimately maladaptive, survival response.

References

- Allen, A. P. Kennedy, P. J. Cryan, J. F. Dinan, T. G. & Clarke, G. (2014). Biological and psychological markers of stress in humans ∞ focus on the Trier Social Stress Test. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 38, 94 ∞ 124.

- Ansell, E. B. Gu, C. Tuit, K. & Sinha, R. (2012). Dehydroepiandrosterone to cortisol ratio ∞ a new biomarker for stress responsivity and resilience. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(11), 1855 ∞ 1863.

- Charmandari, E. Tsigos, C. & Chrousos, G. (2005). Endocrinology of the stress response. Annual Review of Physiology, 67, 259-284.

- Gjerstad, J. K. Lightman, S. L. & Spiga, F. (2018). Role of HPA axis and stress in obesity. Neuropharmacology, 136(Pt B), 125 ∞ 137.

- Silverman, M. N. & Sternberg, E. M. (2012). Glucocorticoid regulation of inflammation and its functional correlates ∞ from HPA axis to glucocorticoid receptor dysfunction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1261(1), 55 ∞ 63.

- Smith, S. M. & Vale, W. W. (2006). The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 8(4), 383 ∞ 395.

- Stephens, M. A. & Wand, G. (2012). Stress and the HPA axis ∞ role of glucocorticoids in alcohol dependence. Alcohol research ∞ current reviews, 34(4), 468 ∞ 483.

- Whirledge, S. & Cidlowski, J. A. (2010). Glucocorticoids, stress, and fertility. Minerva endocrinologica, 35(2), 109 ∞ 125.

Reflection

You have now traveled through the biological landscape of stress, from the initial perception of a threat to the deep molecular shifts it creates within your cells. This knowledge serves a distinct purpose. It transforms the often-isolating experience of symptoms into a clear, understandable narrative of cause and effect.

The fatigue, the brain fog, the changes in your body are not a personal failing; they are the logical consequence of a system operating under immense and prolonged pressure. This understanding is the first, most critical step toward reclaiming your own biology.

Consider the information presented here as a detailed map. A map does not walk the path for you, but it illuminates the terrain, shows you where the obstacles lie, and reveals the potential routes toward your destination. Your personal health journey is unique.

The specific combination of factors that led you here, and the precise interventions that will guide you back to a state of vitality, will be yours alone. The path forward involves listening to your body with this new level of understanding, gathering objective data about your own internal environment, and making conscious, informed decisions.

The potential for reversal is immense, rooted in the inherent adaptability of your own physiology. The process begins now, with the choice to engage with your health not as a passive passenger, but as an empowered and knowledgeable pilot.

Glossary

chronic stress

stress response

cortisol

cortisol levels

nervous system

hpa axis

hpg axis

hpt axis

hormonal imbalance

diurnal cortisol test

dhea

growth hormone

lifestyle interventions

testosterone replacement therapy

anastrozole

peptide therapy

sermorelin

pregnenolone steal

glucocorticoid receptor