Fundamentals

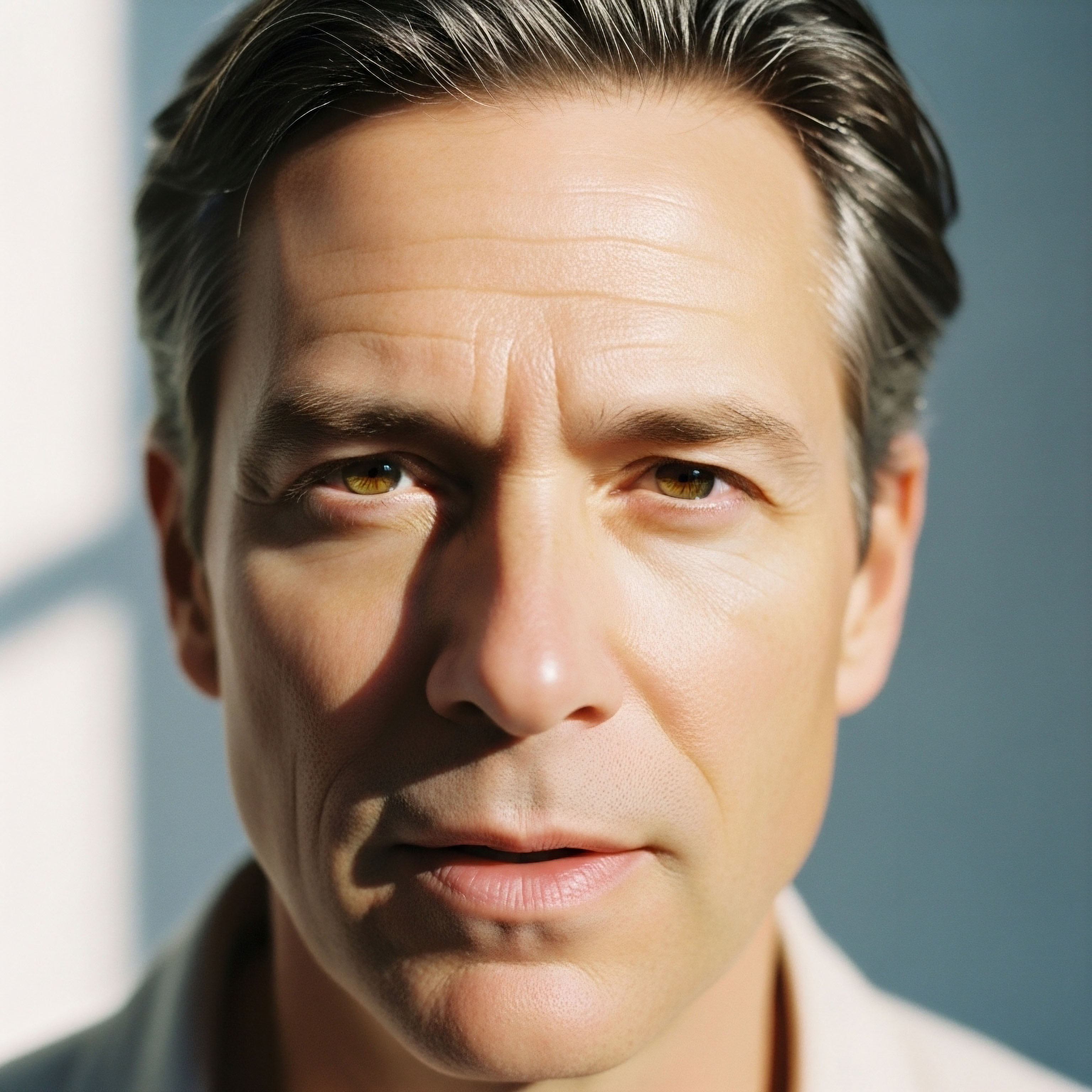

Perhaps you have noticed a subtle shift in your facial contours, a softening or a fullness that was not present before. This experience, often dismissed as a simple consequence of aging or weight fluctuations, frequently carries a deeper biological message.

Your body communicates through a complex network of internal messengers, and changes in facial fat distribution can be a quiet yet significant signal from this intricate system. Understanding these signals marks the initial step in reclaiming your vitality and overall function.

The human face, a canvas of expression and identity, holds various types of fat. Subcutaneous fat, positioned just beneath the skin, contributes significantly to facial volume and shape. This fat is not merely inert padding; it is a dynamic tissue, actively participating in metabolic processes and responding to systemic influences. The distribution and volume of this facial subcutaneous fat are not static; they are subject to a constant interplay of genetic predispositions, lifestyle choices, and, critically, hormonal balance.

The Body’s Internal Messaging System

Hormones serve as the body’s primary communication network, orchestrating virtually every physiological process. Produced by various glands that form the endocrine system, these chemical messengers travel through the bloodstream to target cells, where they elicit specific responses. This system operates on a sophisticated feedback loop, ensuring that hormone levels remain within a precise range to maintain optimal function.

When this delicate balance is disrupted, the effects can ripple throughout the body, influencing everything from energy levels and mood to the very structure of your facial features.

Consider the profound influence of these messengers on fat metabolism. Adipose tissue, the scientific term for body fat, is not just a storage depot for excess energy. It is an active endocrine organ itself, producing its own hormones and responding to signals from other glands.

The way your body stores and mobilizes fat is directly governed by these hormonal instructions. Different hormones can encourage fat accumulation in specific areas or promote its breakdown, shaping your physical form in ways that might surprise you.

Changes in facial fat often reflect deeper shifts within the body’s hormonal communication system.

Hormonal Influences on Adipose Tissue

Several key hormonal players exert significant influence over fat distribution. Cortisol, often called the “stress hormone,” plays a role in regulating metabolism and inflammation. Prolonged elevation of cortisol can lead to increased fat storage, particularly in central areas of the body, including the face. This can result in a more rounded facial appearance, sometimes described as “moon face.” The adrenal glands, responsible for cortisol production, are highly responsive to chronic stress, illustrating how daily pressures can manifest physically.

Thyroid hormones, produced by the thyroid gland, are metabolic regulators. They control the rate at which your body uses energy. An underactive thyroid, a condition known as hypothyroidism, can slow metabolism, leading to weight gain and fluid retention, which may contribute to a puffy facial appearance. Conversely, an overactive thyroid, or hyperthyroidism, can accelerate metabolism, potentially leading to fat loss. The thyroid’s influence extends to every cell, underscoring its systemic importance.

Sex hormones, including estrogen and testosterone, also play a significant part in shaping body composition and fat distribution. While often associated with reproductive health, these hormones exert widespread effects on metabolic function in both men and women. Fluctuations or imbalances in these hormones can alter where fat is stored, including the delicate fat pads of the face.

Understanding these foundational concepts provides a lens through which to view changes in your own facial contours, moving beyond superficial observations to a deeper appreciation of your biological systems.

Intermediate

The subtle shifts in facial fat distribution, as previously discussed, are often direct manifestations of deeper hormonal dynamics. Moving beyond general principles, we can examine specific endocrine agents and therapeutic protocols that directly influence metabolic function and, consequently, the deposition of subcutaneous fat, including that within the face. This section will clarify the mechanisms by which targeted interventions can help recalibrate your system, aiming to restore a more balanced metabolic state and, by extension, a more optimal facial contour.

How Do Hormonal Imbalances Affect Facial Fat?

The intricate relationship between hormones and adipose tissue extends to the face, where specific fat pads are particularly sensitive to systemic changes. When certain hormones are out of balance, these fat pads can either expand or diminish, altering facial aesthetics.

For instance, an excess of cortisol, often stemming from chronic stress or adrenal dysfunction, can lead to increased fat deposition in the cheeks and jawline, contributing to a fuller, sometimes swollen appearance. This is a direct consequence of cortisol’s role in promoting adipogenesis, the creation of new fat cells, and lipogenesis, the storage of fat, particularly in visceral and facial depots.

Conversely, a decline in hormones like testosterone and growth hormone can lead to a reduction in lean muscle mass and an increase in overall adiposity, which may also affect facial contours. Testosterone, a powerful anabolic hormone in both men and women, helps maintain muscle mass and a healthy metabolic rate.

When testosterone levels are suboptimal, the body may favor fat storage over muscle preservation, potentially leading to a less defined facial structure. Growth hormone, another anabolic agent, is crucial for tissue repair, metabolic regulation, and maintaining youthful tissue integrity. Its decline can contribute to a loss of skin elasticity and changes in fat distribution.

Targeted hormonal interventions can help rebalance metabolic function, influencing facial fat distribution.

Targeted Hormonal Optimization Protocols

Addressing these hormonal imbalances requires a precise, individualized approach. Clinical protocols aim to restore physiological levels of these vital messengers, thereby supporting the body’s natural capacity for metabolic regulation and tissue maintenance.

Testosterone Replacement Therapy for Men

For men experiencing symptoms of low testosterone, such as reduced energy, decreased muscle mass, and changes in body composition, Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) can be a transformative intervention. A standard protocol often involves weekly intramuscular injections of Testosterone Cypionate (typically 200mg/ml). This exogenous testosterone helps restore circulating levels, supporting metabolic health and promoting a more favorable body composition, which can indirectly influence facial adiposity by improving overall fat-to-muscle ratios.

To maintain the body’s own testosterone production and preserve fertility, Gonadorelin is frequently included, administered as subcutaneous injections twice weekly. This peptide stimulates the pituitary gland to release luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which are essential for testicular function.

Additionally, an oral tablet of Anastrozole, taken twice weekly, may be prescribed to manage estrogen conversion, preventing potential side effects associated with elevated estrogen levels, such as fluid retention that could affect facial appearance. In some cases, Enclomiphene may be incorporated to further support LH and FSH levels, offering another avenue for endogenous testosterone support.

Testosterone Replacement Therapy for Women

Women, too, can experience significant benefits from testosterone optimization, particularly those in pre-menopausal, peri-menopausal, or post-menopausal stages who present with symptoms like irregular cycles, mood fluctuations, hot flashes, or diminished libido. Protocols for women typically involve lower doses of Testosterone Cypionate, often 10 ∞ 20 units (0.1 ∞ 0.2ml) weekly via subcutaneous injection. This precise dosing helps to restore optimal levels without masculinizing side effects, supporting energy, mood, and metabolic balance.

Progesterone is prescribed based on menopausal status, playing a crucial role in female hormonal balance and often mitigating symptoms associated with estrogen dominance. Another option for long-acting testosterone delivery is Pellet Therapy, where small testosterone pellets are inserted subcutaneously, providing a steady release over several months. Anastrozole may also be used in women when appropriate, particularly to manage estrogen levels in specific clinical contexts.

Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy

For active adults and athletes seeking improvements in body composition, recovery, and overall vitality, Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy offers a compelling avenue. These peptides stimulate the body’s natural production of growth hormone, avoiding the direct administration of synthetic growth hormone itself. This approach leverages the body’s own regulatory mechanisms.

Key peptides in this category include ∞

- Sermorelin ∞ A growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) analog that stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete growth hormone.

- Ipamorelin / CJC-1295 ∞ These are GHRH mimetics that also promote growth hormone release, often used in combination for synergistic effects.

- Tesamorelin ∞ A GHRH analog specifically approved for reducing abdominal fat, which can have systemic metabolic benefits.

- Hexarelin ∞ Another growth hormone secretagogue that can promote growth hormone release.

- MK-677 ∞ An oral growth hormone secretagogue that increases growth hormone and IGF-1 levels.

These peptides can contribute to improved lean muscle mass, reduced adiposity, enhanced sleep quality, and accelerated tissue repair, all of which contribute to a more vibrant appearance, including facial contours.

Other Targeted Peptides

Beyond growth hormone secretagogues, other peptides address specific aspects of health that can indirectly influence overall well-being and appearance. PT-141, for instance, targets sexual health by acting on melanocortin receptors in the brain, improving libido and sexual function. While not directly influencing facial fat, improvements in overall vitality and stress reduction can contribute to a healthier appearance.

Pentadeca Arginate (PDA) is utilized for tissue repair, healing, and inflammation modulation. By supporting cellular regeneration and reducing systemic inflammation, PDA contributes to overall tissue health, which can be reflected in skin quality and the underlying facial structures.

The following table summarizes the primary hormonal influences on facial fat distribution and the corresponding therapeutic approaches ∞

| Hormone Imbalance | Potential Facial Fat Effect | Relevant Therapeutic Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Elevated Cortisol | Increased facial fullness, “moon face” | Stress management, adrenal support, specific medications if Cushing’s is present |

| Low Testosterone (Men) | Reduced facial definition, increased adiposity | Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) |

| Low Testosterone (Women) | Subtle changes in facial contour, metabolic shifts | Low-dose Testosterone Cypionate, Pellet Therapy |

| Low Growth Hormone | Loss of youthful tissue integrity, altered fat metabolism | Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy (Sermorelin, Ipamorelin) |

| Hypothyroidism | Puffy facial appearance, fluid retention | Thyroid hormone replacement |

Academic

To truly comprehend how hormonal balance shapes subcutaneous fat distribution in the face, we must venture into the intricate molecular and cellular landscapes that govern adipose tissue dynamics. This deep exploration moves beyond superficial observations, examining the precise mechanisms by which endocrine signals interact with adipocytes and the broader metabolic environment. The face, far from being an isolated anatomical region, serves as a sensitive barometer of systemic metabolic and hormonal health, reflecting the complex interplay of various biological axes.

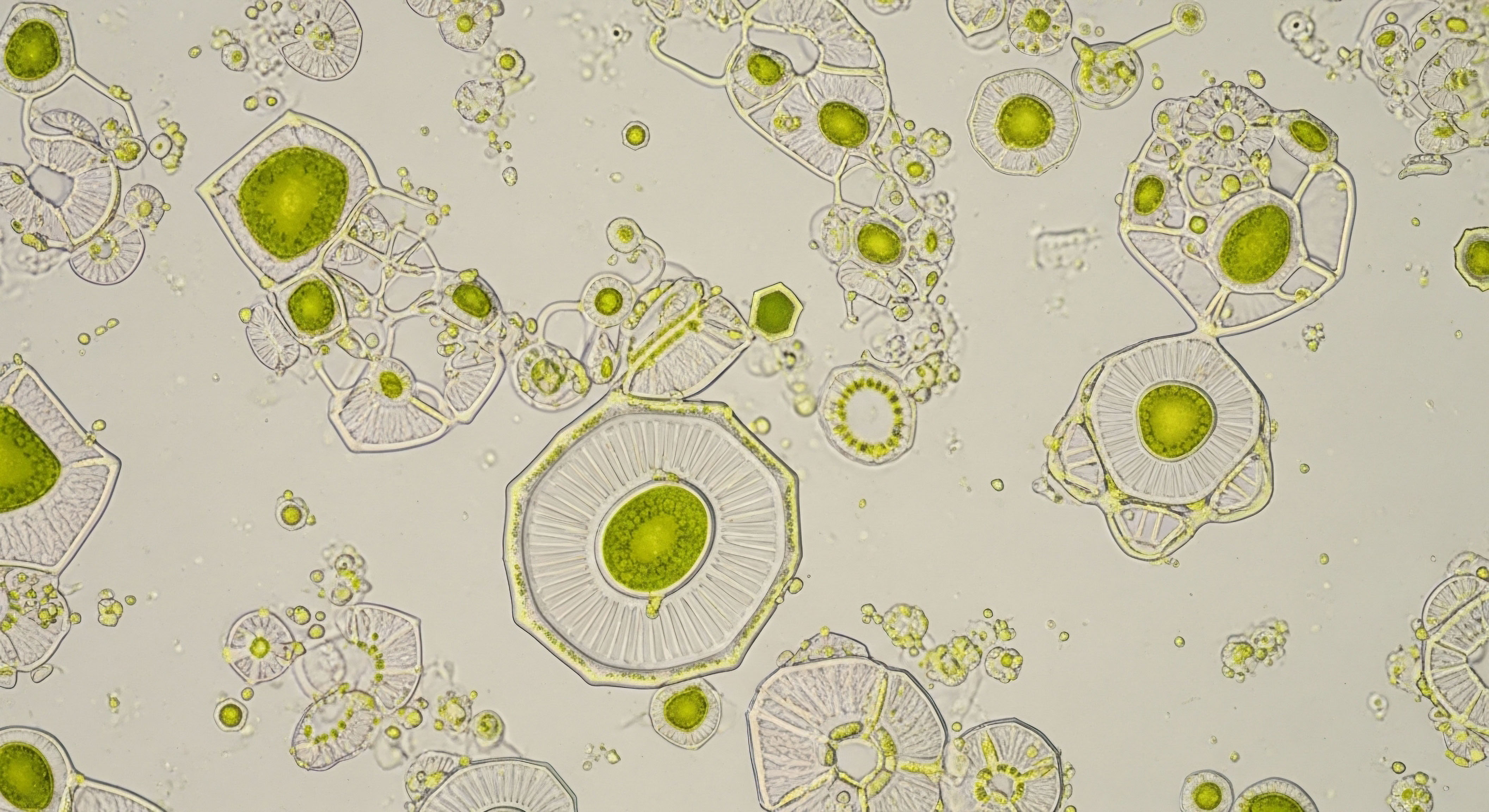

Adipose Tissue Biology and Facial Depots

Adipose tissue, once considered a passive energy reservoir, is now recognized as a highly active endocrine organ. Adipocytes, the primary cells of adipose tissue, possess a diverse array of hormone receptors, allowing them to respond to systemic signals. Facial subcutaneous fat is organized into distinct anatomical compartments or fat pads, such as the malar, buccal, and periorbital pads.

These specific depots exhibit unique metabolic characteristics and hormonal sensitivities. Research indicates that certain facial fat pads may be more susceptible to the lipogenic (fat-storing) effects of hormones like cortisol, while others might be more responsive to the lipolytic (fat-mobilizing) actions of growth hormone or catecholamines.

The cellular machinery within adipocytes, including enzymes like lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), dictates the uptake and release of fatty acids. LPL promotes the storage of triglycerides within adipocytes, while HSL facilitates their breakdown and release. The activity of these enzymes is tightly regulated by hormonal signals.

For instance, insulin promotes LPL activity, encouraging fat storage, while catecholamines stimulate HSL, promoting fat mobilization. Understanding the differential expression and regulation of these enzymes in various facial fat depots is crucial for appreciating how systemic hormonal shifts translate into localized changes in facial contour.

Facial fat pads are metabolically active and uniquely responsive to specific hormonal signals.

Interplay of Endocrine Axes and Metabolic Pathways

The human endocrine system operates as a symphony of interconnected axes, where the function of one gland directly influences others. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, responsible for the stress response, profoundly impacts fat metabolism. Chronic activation of the HPA axis leads to sustained elevation of cortisol.

Cortisol not only promotes central and facial fat accumulation but also induces insulin resistance, further exacerbating metabolic dysfunction. This insulin resistance can lead to higher circulating insulin levels, which in turn can promote lipogenesis in insulin-sensitive fat depots, including those in the face.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, governing sex hormone production, also plays a critical role. Testosterone, in both men and women, contributes to maintaining lean body mass and a favorable metabolic profile. Low testosterone levels are associated with increased visceral adiposity and systemic inflammation, which can indirectly affect facial fat by altering overall metabolic health.

Estrogen, particularly in its fluctuating levels during perimenopause and post-menopause, influences fat distribution. While estrogen generally promotes subcutaneous fat storage in the hips and thighs in pre-menopausal women, its decline can lead to a shift towards more central and potentially facial fat accumulation.

The thyroid axis, through its production of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4), regulates basal metabolic rate. Hypothyroidism slows metabolism, leading to reduced energy expenditure and often generalized weight gain, including fluid retention that can manifest as facial puffiness. These interconnected axes highlight that facial fat changes are rarely isolated events; they are often downstream effects of broader systemic dysregulation.

Molecular Mechanisms of Peptide Action

Peptide therapies offer a sophisticated approach to modulating these complex systems. Their actions are highly specific, often targeting particular receptors or signaling pathways.

- Sermorelin and Ipamorelin/CJC-1295 ∞ These peptides act as growth hormone secretagogues, binding to specific receptors on somatotroph cells in the anterior pituitary gland. This binding stimulates the pulsatile release of endogenous growth hormone. Growth hormone then exerts its effects through the Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) pathway. IGF-1 is a potent anabolic hormone that promotes protein synthesis, lipolysis (fat breakdown), and glucose utilization. The enhanced lipolysis can contribute to a reduction in overall adiposity, including facial fat, while improved protein synthesis supports tissue integrity.

- Tesamorelin ∞ This synthetic GHRH analog specifically targets visceral adipose tissue. Its mechanism involves binding to GHRH receptors, leading to increased growth hormone secretion and subsequent reduction in visceral fat. While its primary target is visceral fat, the systemic metabolic improvements, such as improved insulin sensitivity and reduced inflammation, can have beneficial ripple effects on subcutaneous fat depots throughout the body, including the face.

- PT-141 (Bremelanotide) ∞ This peptide acts as a melanocortin receptor agonist, primarily targeting MC3R and MC4R receptors in the central nervous system. Its primary clinical application is for sexual dysfunction, but its influence on central pathways underscores the interconnectedness of neurological and endocrine systems. While not directly affecting facial fat, its role in improving overall well-being and reducing stress can indirectly support a healthier physiological state.

- Pentadeca Arginate (PDA) ∞ This peptide is being explored for its tissue repair and anti-inflammatory properties. Its mechanism involves modulating cellular signaling pathways related to inflammation and tissue regeneration. By reducing chronic low-grade inflammation, which is often associated with metabolic dysfunction and increased adiposity, PDA can contribute to a healthier cellular environment. This systemic anti-inflammatory effect can support overall tissue health, potentially improving skin quality and the underlying structures of the face.

The following table provides a deeper look into the physiological effects of key hormones and peptides on fat metabolism ∞

| Hormone/Peptide | Primary Metabolic Action | Receptor/Pathway | Potential Impact on Facial Fat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol | Promotes lipogenesis, insulin resistance | Glucocorticoid receptors (GR) | Increased fat deposition, particularly in cheeks/jawline |

| Testosterone | Promotes lipolysis, lean mass maintenance | Androgen receptors (AR) | Supports definition, reduces overall adiposity |

| Growth Hormone | Promotes lipolysis, protein synthesis | Growth Hormone Receptor (GHR), IGF-1 pathway | Reduces adiposity, improves tissue integrity |

| Sermorelin/Ipamorelin | Stimulates endogenous GH release | GHRH receptors on pituitary | Indirectly reduces adiposity via GH/IGF-1 effects |

| Tesamorelin | Reduces visceral fat, improves insulin sensitivity | GHRH receptors | Systemic metabolic improvement, indirect facial benefit |

Can Systemic Inflammation Influence Facial Adiposity?

Chronic low-grade inflammation, a state often accompanying metabolic dysfunction, also plays a role in adipose tissue remodeling. Inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-alpha and IL-6, can alter adipocyte function, promoting insulin resistance and contributing to dysfunctional fat storage. Adipose tissue itself can be a source of these inflammatory mediators, creating a vicious cycle.

Addressing systemic inflammation through targeted interventions, including peptide therapies like PDA, can therefore contribute to a healthier metabolic environment, potentially influencing the composition and distribution of facial fat. The intricate dance between inflammation, hormones, and adipocyte function underscores the systemic nature of facial changes.

References

- Guyton, Arthur C. and John E. Hall. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 14th ed. Elsevier, 2020.

- Boron, Walter F. and Emile L. Boulpaep. Medical Physiology. 3rd ed. Elsevier, 2017.

- Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines. “Androgen Deficiency in Men ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 102, no. 11, 2017, pp. 3864-3892.

- Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines. “Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 101, no. 2, 2016, pp. 364-389.

- Veldhuis, Johannes D. et al. “Physiological Regulation of Growth Hormone Secretion.” Growth Hormone & IGF Research, vol. 16, no. 2, 2006, pp. S1-S10.

- Fried, Stephen K. et al. “Regional Differences in Adipose Tissue Metabolism in Humans.” International Journal of Obesity, vol. 24, no. 10, 2000, pp. 1298-1306.

- Rosen, Clifford J. and Michael L. Johnson. “Regulation of Bone and Fat by the Growth Hormone/IGF-I Axis.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 91, no. 11, 2006, pp. 4229-4233.

- Miller, K. K. et al. “Tesamorelin, a Growth Hormone-Releasing Factor Analog, in the Treatment of HIV-Associated Lipodystrophy.” Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol. 54, no. 12, 2012, pp. 1754-1763.

- Traish, Abdulmaged M. et al. “The Dark Side of Testosterone Deficiency ∞ I. Metabolic and Cardiovascular Consequences.” Journal of Andrology, vol. 27, no. 5, 2006, pp. 547-558.

- Davis, Susan R. et al. “Testosterone for Women ∞ The Clinical Practice Guideline of The Endocrine Society.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 101, no. 10, 2016, pp. 3653-3669.

Reflection

The journey to understanding your own biological systems is a deeply personal one, often beginning with subtle cues from your body. The insights shared here, from the foundational roles of hormones to the intricate mechanisms of targeted peptide therapies, are not merely academic concepts.

They represent pathways to a more profound connection with your own physiology. Recognizing that changes in facial fat distribution can signal broader metabolic and hormonal shifts transforms a superficial concern into an opportunity for deeper self-awareness and proactive health management.

This knowledge serves as a compass, guiding you toward informed decisions about your well-being. It underscores that vitality and optimal function are not accidental occurrences but rather the outcome of a finely tuned internal environment.

Your body possesses an innate intelligence, and by understanding its language ∞ the language of hormones and metabolic pathways ∞ you gain the capacity to support its natural inclination toward balance. This understanding is the initial step; the subsequent steps involve personalized guidance, translating these complex principles into a protocol that aligns with your unique biological blueprint and personal aspirations.