Fundamentals

A Systemic Disconnect

You have followed the protocols. You have adjusted your diet, managed your sleep, and engaged in consistent physical activity. Yet, a persistent feeling of being unwell remains, a subtle but constant friction against your sense of vitality. This experience, where the inputs do not seem to match the outputs, is a common starting point for a deeper investigation into personal biology.

It suggests that the body’s internal communication systems may be operating with interference. The feeling is not imagined; it is a physiological signal that a foundational element of your health architecture requires attention. The disconnect often lies in the complex relationship between two of the body’s most powerful systems ∞ the endocrine network and the gut microbiome.

The endocrine system functions as the body’s primary long-range messaging service. It consists of glands that produce and secrete hormones, which are chemical messengers that travel through the bloodstream to target cells and organs, regulating processes from metabolism and growth to mood and reproductive cycles.

Think of it as a highly sophisticated postal service, where specific molecules are sent from a central office (a gland like the thyroid or adrenal) with a precise address (a receptor on a target cell) to deliver a specific instruction. When this system is calibrated, the body operates with a seamless rhythm. When the signals are disrupted, the effects are felt system-wide, manifesting as fatigue, metabolic changes, or shifts in cognitive function.

The body’s internal state is a direct reflection of the clarity and efficiency of its hormonal communication channels.

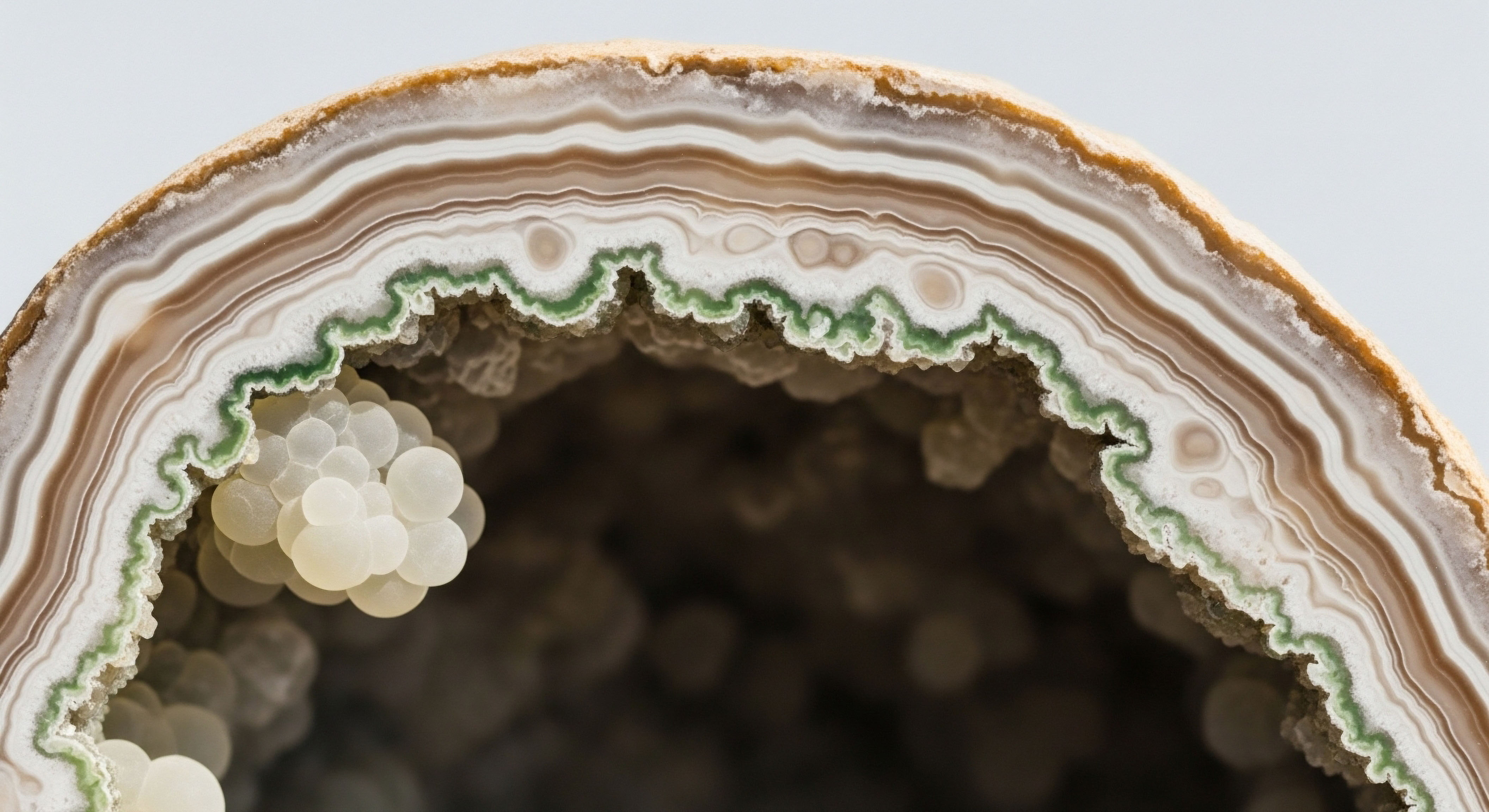

Residing within the gastrointestinal tract is the gut microbiome, a dense and dynamic community of trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. This internal ecosystem is far from being a passive passenger. It is an active, metabolic organ in its own right, performing functions that are indispensable to human health.

These microbes break down dietary fibers that human enzymes cannot, producing vital compounds in the process. They synthesize certain vitamins, train the immune system, and fortify the gut barrier against pathogens. This microbial collective is a biochemical powerhouse, constantly interacting with and influencing host physiology.

The First Point of Contact

The connection between gut health and hormonal function begins with the direct metabolic activity of these resident microbes. They are not merely living within us; they are actively participating in our biochemistry. One of the most significant ways they do this is by producing and modulating molecules that are either hormones themselves or influence hormonal pathways.

For instance, certain bacterial species can synthesize neurotransmitters like serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), chemicals that have profound effects on mood and the body’s stress response systems. Approximately 95% of the body’s serotonin, a key regulator of mood and gut motility, is produced in the gut, a process heavily influenced by the microbial population.

A state of dysbiosis, or an imbalance in the composition and function of the gut microbiome, can disrupt these processes. This imbalance might mean a loss of beneficial species, an overgrowth of potentially harmful ones, or a general reduction in microbial diversity.

When dysbiosis occurs, the gut environment can shift from a supportive, symbiotic state to one that generates inflammatory signals. These signals are not confined to the gut. They can enter the systemic circulation, contributing to a low-grade, chronic inflammation that places a significant burden on the entire body, including the endocrine system.

This inflammatory state can interfere with hormone production, signaling, and receptor sensitivity, creating a cascade of downstream effects that manifest as the very symptoms that defy simple solutions.

Therefore, the integrity of the gut microbiome is a prerequisite for effective endocrine function. Before considering advanced hormonal support protocols, it is essential to ensure that the foundational environment of the gut is stable and healthy. An inflamed, dysbiotic gut can act as a source of constant static, interfering with the clear hormonal signals required for optimal health. Addressing this foundational layer is the first, most logical step in recalibrating the body’s complex internal communication network.

What Is the Consequence of a Dysbiotic Gut?

A dysbiotic gut environment has consequences that extend far beyond the digestive tract, directly impacting hormonal regulation. The breakdown of the intestinal barrier, a condition often referred to as increased intestinal permeability or “leaky gut,” is a primary outcome.

In a healthy state, the cells lining the intestine are tightly packed, forming a selective barrier that allows nutrients to pass into the bloodstream while blocking toxins, undigested food particles, and pathogens. In a state of dysbiosis and inflammation, these junctions can loosen.

This allows substances like lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the outer membrane of certain bacteria, to “leak” into the bloodstream. LPS is a potent inflammatory trigger, signaling the immune system to mount a response. This systemic inflammation directly affects endocrine glands, impairing their ability to produce hormones efficiently and altering how target tissues respond to hormonal signals. This mechanism links the state of the gut directly to systemic metabolic and hormonal health.

| Characteristic | Healthy Gut Microbiome | Dysbiotic Gut Microbiome |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial Diversity |

High diversity, with a rich variety of beneficial bacterial species. |

Low diversity, often with an overgrowth of one or more pathogenic or opportunistic species. |

| Gut Barrier Integrity |

Strong tight junctions between intestinal cells, maintaining a selective barrier. |

Compromised tight junctions, leading to increased intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”). |

| Metabolic Output |

Production of beneficial short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which nourishes gut cells and has anti-inflammatory effects. |

Reduced SCFA production and potential increase in inflammatory compounds like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) entering circulation. |

| Systemic Impact |

Supports balanced immune function and stable endocrine signaling. |

Promotes chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation, disrupting hormonal and metabolic regulation. |

Intermediate

Microbial Regulation of Hormonal Circuits

The influence of the gut microbiome on the endocrine system moves beyond general inflammation to highly specific, targeted molecular interactions. The microbial community acts as a sophisticated regulator, capable of fine-tuning the levels of key hormones circulating throughout the body.

This is achieved through a variety of enzymatic processes that directly modify hormonal molecules, effectively controlling their activity and bioavailability. Understanding these mechanisms reveals why a healthy gut is not just beneficial but mechanically necessary for the success of any endocrine support protocol.

One of the most well-documented examples of this regulation is the estrobolome. This term refers to the specific collection of gut bacteria and their genes that are capable of metabolizing estrogens. After the liver processes estrogens for excretion, it conjugates them, essentially packaging them up to be removed from the body.

However, certain gut bacteria produce an enzyme called β-glucuronidase. This enzyme can “un-package” or deconjugate these estrogens in the gut, allowing them to be reabsorbed back into the bloodstream. A balanced estrobolome helps maintain estrogen homeostasis. In a state of dysbiosis, the activity of β-glucuronidase can be either too high or too low.

Excessively high activity leads to estrogen recirculation and can contribute to conditions of estrogen excess. Conversely, low activity can lead to diminished estrogen levels. This microbial control panel has direct implications for women undergoing hormonal transitions like perimenopause or for those on hormone replacement therapy, as the gut’s activity can significantly alter the intended dose and effect of administered estrogens.

Androgen and Thyroid Axis Interplay

The microbiome’s regulatory capacity extends to male hormones as well. Research demonstrates a clear connection between gut health and testosterone levels. Systemic inflammation, often originating from gut dysbiosis and the translocation of LPS, can suppress the function of Leydig cells in the testes, which are responsible for producing the majority of a man’s testosterone.

Furthermore, just as with estrogen, gut bacteria can metabolize androgens. Studies have shown that the gut microbiota is involved in the deconjugation of testosterone and its potent metabolite, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), within the intestine. An imbalanced gut microbiome can disrupt this process, potentially affecting local and systemic androgen balance. This is a critical consideration for men on Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), as the state of their gut could influence the metabolism and ultimate efficacy of the treatment.

The gut microbiome functions as a secondary regulatory organ for sex hormones, capable of modifying their circulation and availability.

The thyroid axis is also subject to microbial influence. The thyroid gland produces predominantly thyroxine (T4), which is a relatively inactive prohormone. For the body to use it effectively, T4 must be converted into the more biologically active form, triiodothyronine (T3).

A significant portion of this conversion, up to 20%, occurs in the gut and is dependent on the activity of an enzyme called intestinal sulfatase, which is produced by gut bacteria. A dysbiotic gut with insufficient beneficial bacteria can impair this T4-to-T3 conversion process.

A person may have adequate T4 levels according to lab results, but if the gut-mediated conversion is inefficient, they may still experience symptoms of hypothyroidism. This highlights a scenario where treating the thyroid directly without addressing the underlying gut dysfunction may yield incomplete results.

How Does Gut Health Affect Clinical Protocols?

The state of the gut microbiome is a determining factor in the outcome of specific endocrine system support protocols. Its influence can determine how a therapeutic agent is absorbed, metabolized, and utilized by the body. For individuals undertaking these precise biochemical recalibration strategies, ignoring gut health is akin to building a precision engine on an unstable foundation. The interactions can be direct and clinically significant.

Consider the standard protocols for hormone optimization:

- Oral Medications ∞ Any orally administered medication, such as Progesterone tablets or the Aromatase Inhibitor Anastrozole, must pass through the gastrointestinal system. The composition of the gut microbiome can affect the absorption and metabolism of these drugs. An inflamed gut lining or an imbalance in metabolic enzymes produced by bacteria could alter the bioavailability of the medication, leading to either a reduced effect or unexpected side effects. For example, the efficacy of Anastrozole, used to control estrogen conversion in men on TRT, could be modulated by the same estrobolome that influences endogenous estrogen.

- Injectable Therapies ∞ While injectable therapies like Testosterone Cypionate or peptide hormones (e.g. Sermorelin, Ipamorelin) bypass first-pass metabolism in the gut, their overall effectiveness is still subject to the body’s systemic inflammatory status. If a dysbiotic gut is consistently releasing LPS into the bloodstream, the resulting chronic inflammation creates a hostile environment for hormonal signaling. This inflammation can increase levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), which binds to testosterone and makes it unavailable to tissues. It can also blunt the sensitivity of cellular receptors to both testosterone and growth hormone peptides, meaning that even with adequate dosage, the body’s tissues cannot fully respond to the signal.

- Fertility Protocols ∞ In protocols designed to stimulate natural testosterone production or fertility in men, such as those using Gonadorelin, Clomid, or Tamoxifen, the goal is to restore the proper function of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This axis is highly sensitive to systemic stress, including the inflammatory stress originating from a compromised gut. Chronic inflammation can suppress pituitary output of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), the very signals that Gonadorelin aims to stimulate, thereby working against the protocol’s objective.

| Clinical Protocol | Key Medications | Potential Gut Microbiome Interference |

|---|---|---|

| Men’s TRT |

Testosterone Cypionate, Gonadorelin, Anastrozole |

Systemic inflammation from dysbiosis can increase SHBG, reducing free testosterone. Gut metabolism can alter oral Anastrozole efficacy. |

| Women’s HRT |

Testosterone Cypionate (low dose), Progesterone (oral), Pellets |

The estrobolome directly modulates estrogen and progesterone levels, potentially altering the balance achieved by therapy. |

| Post-TRT / Fertility |

Gonadorelin, Clomid, Tamoxifen |

Inflammatory signals from the gut can suppress the HPG axis, counteracting the stimulating effect of the medications. |

| Growth Hormone Peptides |

Sermorelin, Ipamorelin / CJC-1295, Tesamorelin |

Chronic inflammation can blunt cellular receptor sensitivity to growth hormone signaling, reducing the anabolic and restorative benefits. |

Academic

The Estrobolome a Deep Dive into Microbial Endocrine Regulation

The concept of the estrobolome represents a sophisticated evolution in our understanding of endocrinology, moving from a host-centric model to a symbiotic one where microbial life actively participates in steroid hormone metabolism. This collection of enteric bacterial genes encoding estrogen-metabolizing enzymes exerts a level of control over estrogen homeostasis that is both clinically relevant and mechanistically profound.

The primary biochemical pathway of this influence is the enterohepatic circulation of estrogens. Estrogens, primarily estradiol (E2) and its metabolites, are conjugated in the liver, mainly through glucuronidation, to form water-soluble compounds like estrogen-glucuronide. This process renders them biologically inactive and targets them for excretion via bile into the intestine.

Within the intestinal lumen, the estrobolome intervenes. Bacteria possessing β-glucuronidase (GUS) enzymes can hydrolyze the glucuronic acid moiety from the conjugated estrogen. This enzymatic action, a deconjugation, liberates the estrogen, converting it back into its biologically active, unconjugated form.

This reactivated estrogen can then be reabsorbed through the intestinal mucosa into the portal circulation, returning to the systemic bloodstream. This process effectively creates a secondary regulatory loop for estrogen levels, independent of gonadal production. The composition of the gut microbiota, and therefore the aggregate activity of its GUS enzymes, directly dictates the efficiency of this recycling process.

High GUS activity leads to greater estrogen reabsorption and higher systemic estrogen levels, while low activity results in greater fecal excretion and lower systemic levels.

Enzymatic Machinery and Microbial Players

The bacterial enzymes responsible for this critical function, the β-glucuronidases, are not uniform. They belong to a large and diverse family of glycoside hydrolases. Research has identified specific bacterial phyla, such as Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, as major contributors to the estrobolome.

Within these phyla, genera like Clostridium and Ruminococcus are known to harbor species with potent GUS activity. The genetic diversity of these GUS enzymes allows for the metabolism of a wide range of steroid glucuronides, suggesting a complex and co-evolved relationship between the host and its microbial residents.

The clinical implications of this microbial activity are substantial. An estrobolome characterized by high GUS activity has been associated with an increased risk for the development and progression of estrogen-dependent pathologies. These include certain forms of postmenopausal breast cancer, endometriosis, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

In these conditions, the microbial reactivation of estrogens can contribute to a state of estrogen dominance, where the physiological effects of estrogen are excessive relative to other hormones like progesterone. This understanding reframes these conditions, suggesting a gut-centric component that may be a viable target for intervention. For instance, therapies aimed at modulating the gut microbiome to reduce GUS activity, such as the use of specific probiotics, prebiotics, or dietary interventions, could become adjuncts to standard hormonal treatments.

The enzymatic activity of the estrobolome constitutes a critical control point in systemic estrogen exposure.

This mechanism also has direct consequences for pharmacology, particularly concerning orally administered hormonal therapies. The efficacy and side-effect profile of Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) like Tamoxifen, often used in post-TRT protocols for men or in breast cancer treatment, can be influenced by the estrobolome.

Tamoxifen and its metabolites undergo enterohepatic circulation, and their reactivation by bacterial enzymes can alter their therapeutic concentration and tissue-specific effects. Similarly, the intended balance of hormone replacement therapy in women can be disrupted by a dysbiotic estrobolome, necessitating a clinical approach that considers the patient’s microbial status.

What Are the Broader Implications for Systemic Health?

The regulatory role of the gut microbiome is not limited to a single hormonal axis. The same principles of microbial enzymatic modification and regulation of enterohepatic circulation apply to other steroid hormones, including androgens and glucocorticoids, as well as bile acids, which themselves function as signaling molecules.

The gut microbiota is known to perform a near-complete deconjugation of androgens like testosterone and DHT in the distal intestine, leading to remarkably high concentrations of free, active androgens in the colonic environment. This creates a localized high-androgen environment with potential effects on gut cellular health and creates a reservoir of active hormones that can be reabsorbed.

This systems-level perspective reveals a deeply interconnected network where the gut microbiome acts as a central metabolic and endocrine organ. It communicates with the host’s primary endocrine axes ∞ the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA), Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG), and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axes.

It does so not only through direct hormone modulation but also through the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), neurotransmitters, and by regulating systemic inflammation. A disruption in this microbial hub, therefore, does not result in an isolated problem. It creates systemic dysregulation that can undermine even the most precisely calibrated therapeutic interventions.

A comprehensive clinical approach to endocrine health must, by necessity, include an assessment and optimization of the gut microbiome. It is the biological substrate upon which all other hormonal interventions are built.

- SCFAs and GLP-1 Secretion ∞ The fermentation of dietary fiber by gut bacteria produces SCFAs like butyrate and propionate. These molecules signal to enteroendocrine L-cells in the gut lining to release glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). GLP-1 is a critical hormone for glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity, linking gut microbial activity directly to metabolic health.

- Bile Acid Metabolism ∞ Gut bacteria modify primary bile acids produced by the liver into secondary bile acids. These secondary bile acids act as signaling molecules, binding to receptors like the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and TGR5, which regulate glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, and energy expenditure.

- HPA Axis Modulation ∞ The gut microbiome communicates with the brain via the vagus nerve and through circulating microbial metabolites. This gut-brain axis communication influences the HPA axis, the body’s central stress response system. Dysbiosis has been shown to be associated with HPA axis hyperactivity and altered cortisol patterns, linking gut health directly to stress resilience and adrenal function.

References

- Clarke, Gerard, et al. “The Microbiome-Gut-Brain Axis During Early Life Regulates the Hippocampal Transcriptome and Adult Anxiety-like Behavior.” Molecular Psychiatry, vol. 18, no. 6, 2013, pp. 666-73.

- Colldén, Holger, et al. “The Gut Microbiota Is a Major Regulator of Androgen Metabolism in Intestinal Contents.” American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 317, no. 6, 2019, pp. E1182-E1192.

- He, Shiyun, et al. “Hormone Replacement Therapy Reverses Gut Microbiome and Serum Metabolome Alterations in Premature Ovarian Insufficiency.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 12, 2021, p. 794496.

- Kwa, Mary, et al. “The Estrobolome ∞ Estrogen-Metabolizing Pathways of the Gut Microbiome and Their Relation to Breast Cancer.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 113, no. 8, 2021, pp. 983-994.

- Martin, A. M. et al. “The Gut Microbiome, Its Interaction with the Host, and the Role of Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Synbiotics in the Prevention and Treatment of Metabolic Diseases.” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 10, no. 21, 2021, p. 5143.

- Plottel, Claudia S. and Martin J. Blaser. “The Estrobolome ∞ The Gut Microbiome and Estrogen.” NPJ Biofilms and Microbiomes, vol. 1, 2015, p. 15002.

- Qi, Xinyu, et al. “The Impact of the Gut Microbiota on the Reproductive and Metabolic Endocrine System.” Gut Microbes, vol. 13, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1-21.

- Sánchez-Alcoholado, L. et al. “The Role of the Gut Microbiome in the Development of Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes.” Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 11, 2021, p. 3975.

- Tremaroli, Valentina, and Fredrik Bäckhed. “The Gut Microbiota, Short-Chain Fatty Acids, and Host Metabolism.” Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, vol. 14, no. 10, 2017, pp. 589-605.

- Yatsunenko, Tanya, et al. “Human Gut Microbiome Viewed Across Age and Geography.” Nature, vol. 486, no. 7402, 2012, pp. 222-27.

Reflection

Calibrating the Internal Environment

The information presented here provides a biological and mechanical basis for understanding the symptoms and feelings that arise from a dysregulated internal system. It shifts the perspective from isolated hormonal issues to a more integrated view, where the gut microbiome is a foundational pillar of endocrine health.

The knowledge that microbial communities within you are actively participating in your hormonal balance is a significant realization. It suggests that your daily choices regarding nutrition and lifestyle are not just influencing your own cells, but are also shaping the function of this vast microbial organ.

This understanding is the starting point for a more targeted and personalized approach to your own health. The path forward involves considering how to create an internal environment that supports clear communication between all of your body’s systems, allowing for the restoration of function and vitality.