Fundamentals

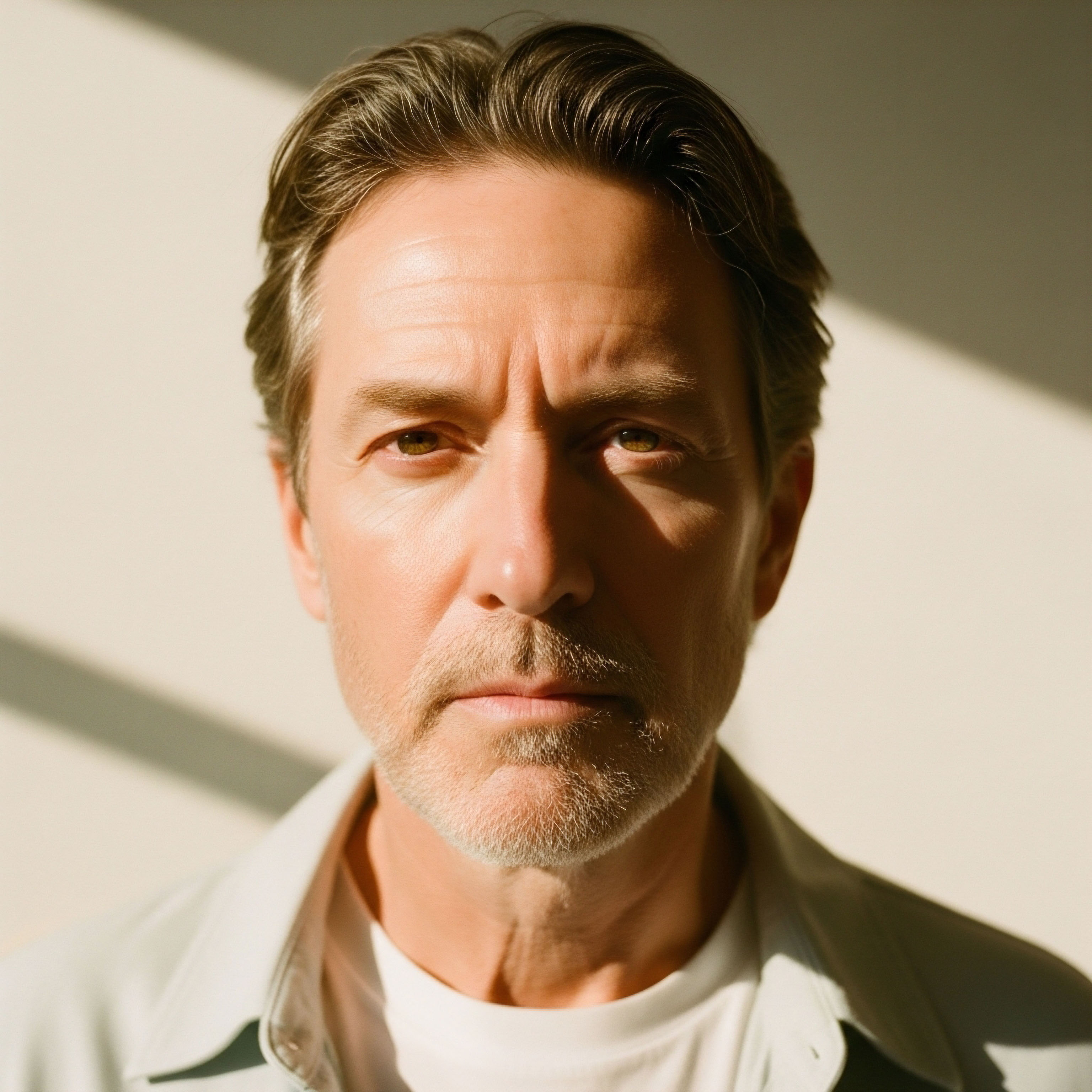

Your journey with a GLP-1 agonist Meaning ∞ A GLP-1 Agonist is a medication class mimicking natural incretin hormone Glucagon-Like Peptide-1. These agents activate GLP-1 receptors, stimulating glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppressing glucagon, slowing gastric emptying, and enhancing satiety. begins with a palpable shift in your body’s daily rhythms. The subtle, yet persistent, decrease in appetite and the novel sensation of fullness are direct communications from your endocrine system, now operating under a new set of instructions.

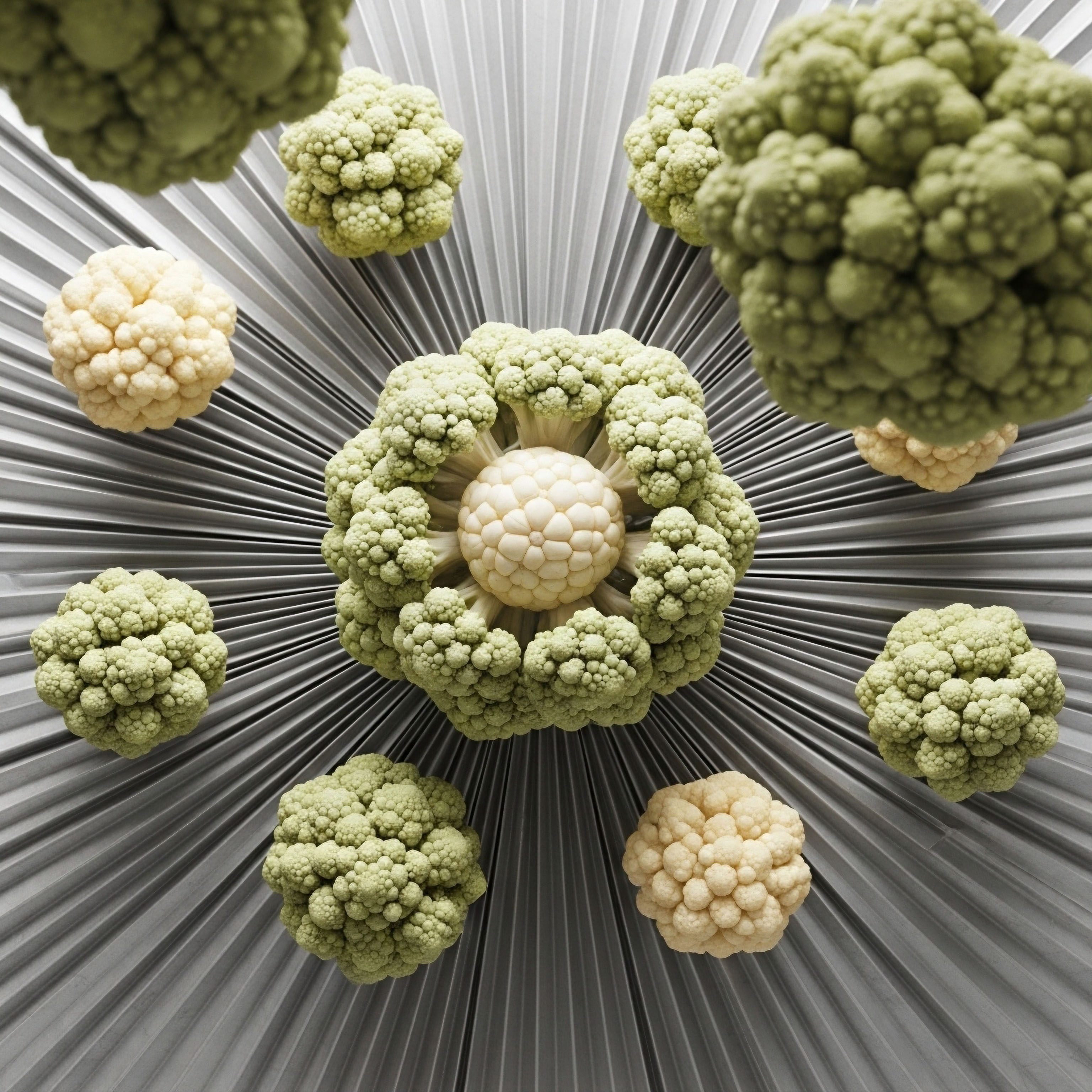

This experience, this internal recalibration, extends far deeper than your stomach. It reaches into the vast, unseen ecosystem within your intestines ∞ the gut microbiome. This universe of trillions of microorganisms is profoundly attuned to the conditions of its environment. When you introduce a GLP-1 agonist, you are fundamentally altering that environment, initiating a cascade of changes that reverberates through your entire physiology.

These medications are synthetic versions of glucagon-like peptide-1, a hormone your own intestines produce in response to a meal. Its natural role is to orchestrate your body’s metabolic response to incoming nutrients. It signals the pancreas to release insulin, tempers the liver’s release of stored sugar, and communicates with the brain to register satiety.

By amplifying this signal, GLP-1 agonists Meaning ∞ GLP-1 Agonists are pharmaceutical compounds mimicking natural glucagon-like peptide-1, an incretin hormone. sustain these effects, leading to improved blood sugar control and a reduced drive to eat. The most immediate physical change you might notice is a slowing of gastric emptying. Your stomach holds onto food for longer periods, which is a primary reason you feel full.

The introduction of a GLP-1 agonist reshapes the internal environment of the gut, prompting a direct response from its resident microbial communities.

This single change in digestive timing creates a new reality for your gut microbiome. The bacteria, archaea, and fungi residing in your colon are heterotrophs; they consume what you provide them. A change in the speed and composition of food arriving in the colon alters the available fuel sources.

Some microbial species will find these new conditions favorable and begin to flourish. Others may find their preferred resources diminished, leading to a reduction in their populations. This process of microbial reorganization is a central, though often unmentioned, aspect of how these powerful therapies achieve their effects. Understanding this connection is the first step in seeing your body as a complete, interconnected system, where a therapeutic intervention in one area produces a powerful, symbiotic response in another.

The Gut as a Responsive Environment

Your gut is an incredibly dynamic organ. It hosts the majority of your immune system and functions as your largest endocrine gland, producing dozens of hormones that regulate your physiology. The microbiome is a key player in all these functions. It digests fibers your own body cannot, producing beneficial compounds like short-chain fatty acids Meaning ∞ Short-Chain Fatty Acids are organic compounds with fewer than six carbon atoms, primarily produced in the colon by gut bacteria fermenting dietary fibers. (SCFAs).

These molecules provide energy to your colon cells, strengthen the gut barrier, and send signals that reduce inflammation throughout the body. The composition of your microbiome, the specific balance of different species, dictates its functional output. A state of healthy balance is often called eubiosis, while an imbalance is termed dysbiosis.

Many chronic metabolic conditions, including obesity and type 2 diabetes, are associated with a state of dysbiosis. GLP-1 agonists appear to nudge this ecosystem back toward a more favorable, eubiotic state.

Intermediate

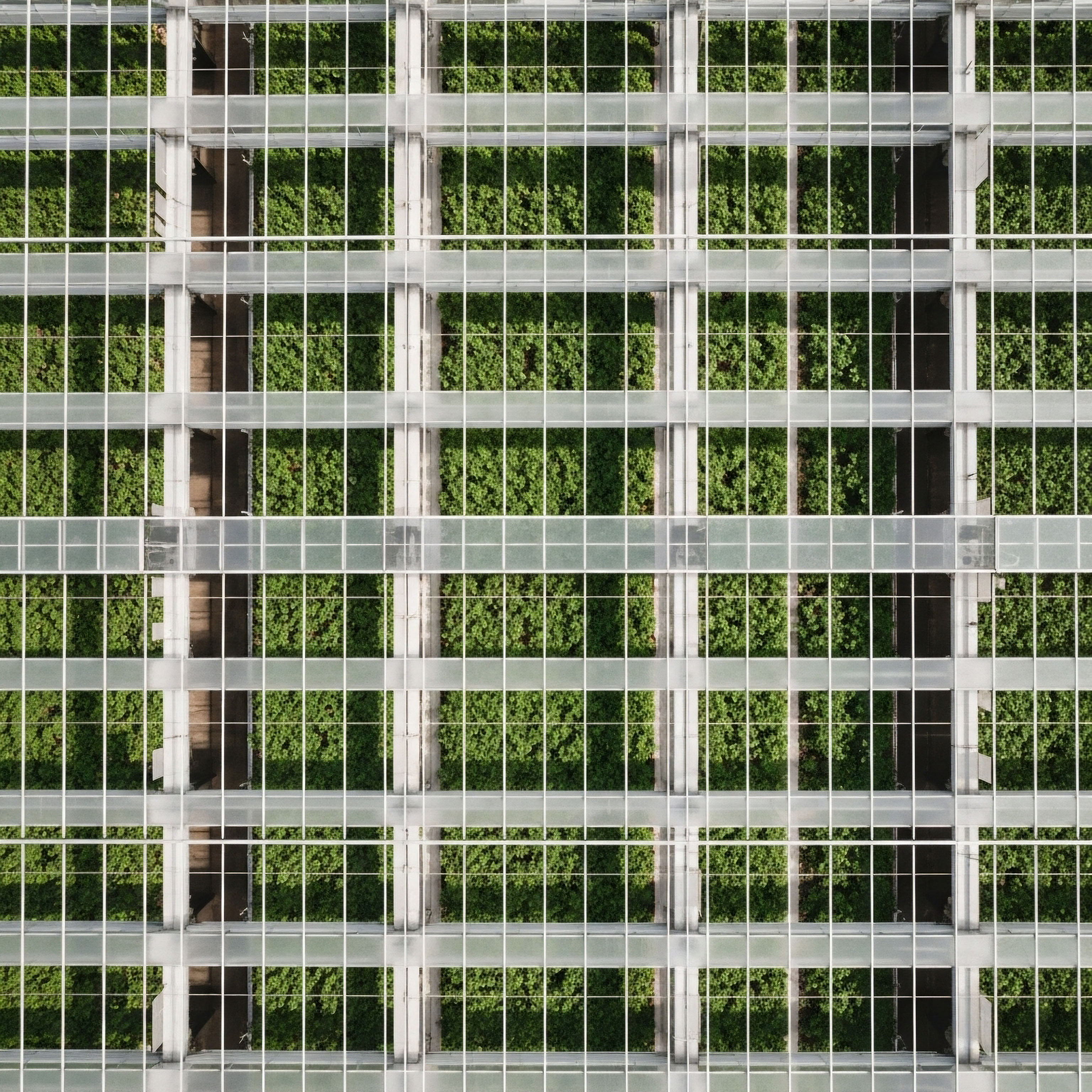

The influence of GLP-1 agonists on the gut microbiome Meaning ∞ The gut microbiome represents the collective community of microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, viruses, and fungi, residing within the gastrointestinal tract of a host organism. unfolds through two primary pathways ∞ indirect modulation via physiological changes and direct signaling interactions within the gut itself. The most significant of these is the indirect effect driven by altered gastrointestinal motility. By slowing gastric emptying, these medications change the nutrient landscape of the entire digestive tract.

Food substrates are exposed to the upper intestine for longer, which can lead to more complete absorption of certain nutrients. Consequently, the profile of undigested carbohydrates and proteins reaching the colon, the primary site of microbial fermentation, is transformed. This change in available “food” for the microbiota is a powerful selective pressure, favoring the growth of microbes that are best adapted to the new nutritional environment.

This physiological shift has profound implications for microbial composition. For instance, a slower transit time can promote the growth of bacteria that are particularly effective at fermenting complex fibers, such as species from the Bacteroidetes phylum. Simultaneously, the reduction in overall food intake associated with GLP-1 therapy means a lower total load of substrates reaches the colon.

This caloric restriction alone is a known factor in shaping microbial communities. The result is a multi-faceted remodeling of the ecosystem, driven by both the timing and the quantity of nutrients delivered to the gut’s microbial inhabitants.

Which Microbial Populations Are Affected?

Clinical research has begun to identify consistent patterns of microbial change associated with GLP-1 agonist use. While effects can vary based on the specific medication, the individual’s baseline health, and their diet, certain trends are emerging. Several studies have shown that these therapies tend to foster the growth of beneficial bacteria while reducing populations linked to metabolic disease.

For example, genera like Akkermansia, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium are often found in greater abundance. Akkermansia muciniphila, in particular, is a keystone species for gut health. It lives in the mucus layer of the intestines and helps maintain the integrity of the gut barrier, preventing inflammatory molecules from leaking into the bloodstream. An increase in Akkermansia is consistently linked with improved metabolic health and lower inflammation.

Conversely, GLP-1 agonists often reduce the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes, a metric that is frequently elevated in individuals with obesity. They can also decrease the prevalence of certain pro-inflammatory bacteria. This curated shift away from a dysbiotic, pro-inflammatory state toward a eubiotic, anti-inflammatory profile is a core component of the therapeutic benefit seen with these medications. The microbiome is not just a passive bystander; it becomes an active participant in the healing process.

A Comparative Look at Different GLP-1 Agonists

Different GLP-1 agonist molecules have shown slightly different effects on the microbiome, reflecting their unique pharmacological properties. The following table summarizes findings from various human and animal studies, providing a snapshot of the current research landscape.

| GLP-1 Agonist | Key Microbial Changes Observed | Associated Metabolic Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Liraglutide |

Increases Akkermansia, Lactobacillus. May decrease overall diversity. Reduces Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. |

Promotes a lean-associated microbial profile, correlating with weight loss and improved glucose metabolism. |

| Exenatide |

Increases Akkermansia and Barnesiella in animal models. In humans, increases Coprococcus and Bifidobacterium. |

Associated with improved metabolic markers and reduced inflammation. |

| Semaglutide |

Animal studies show increases in Akkermansia muciniphila but also potential reductions in overall diversity. |

Weight loss effects have been positively correlated with changes in genera like Helicobacter. |

| Dulaglutide |

Animal studies show increases in Bacteroides and Akkermansia. Human studies show minor shifts, including an increase in Lactobacillus. |

Demonstrates significant anti-inflammatory effects, potentially through modulation of the microbiome. |

What Are the Direct Effects on the Gut?

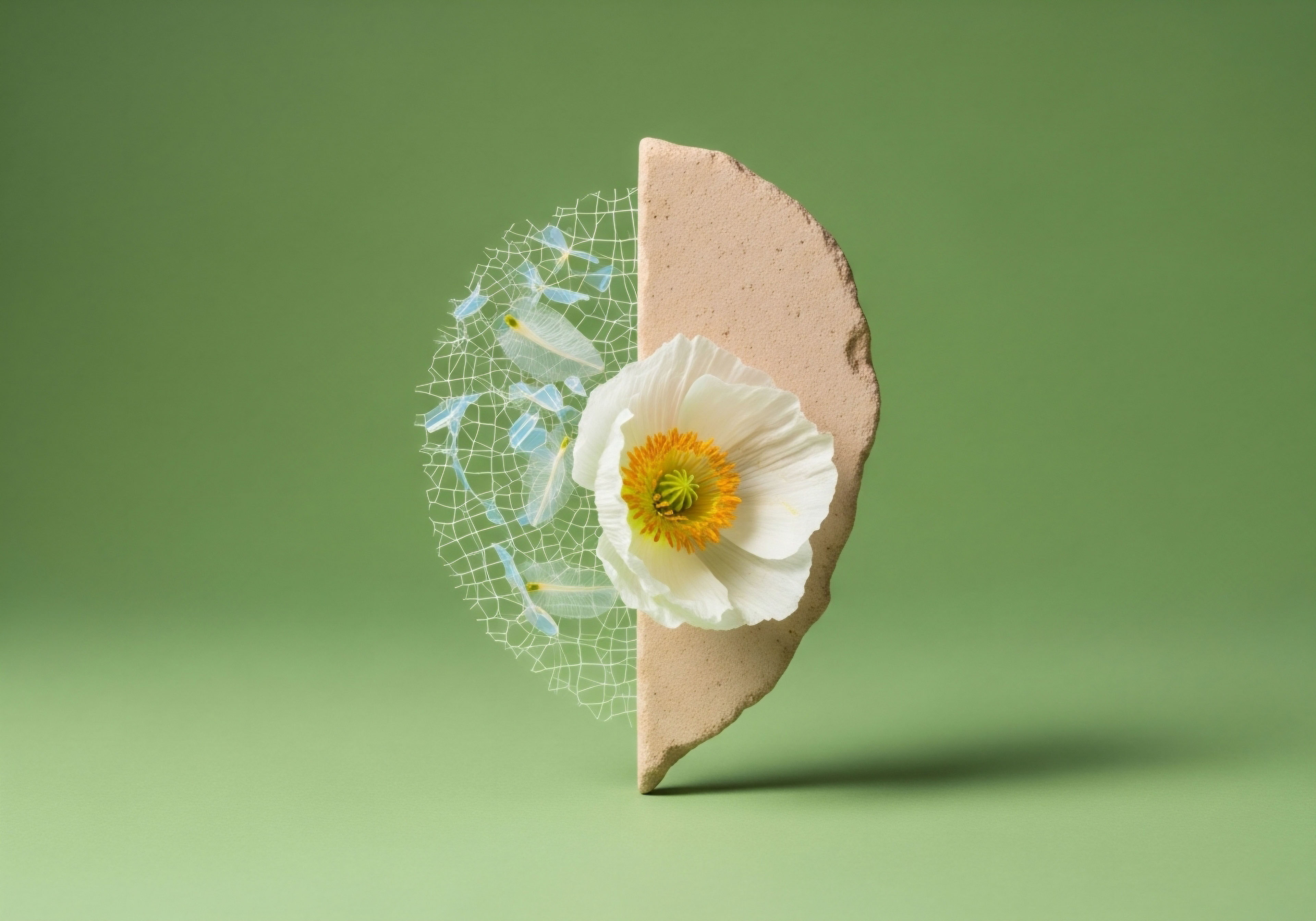

Beyond the indirect effects of altered digestion, there is emerging evidence for direct interactions. The enteroendocrine L-cells that produce the body’s natural GLP-1 are situated within the gut lining, right alongside other intestinal cells and in close proximity to the microbiome. These cells, as well as other cells in the intestinal epithelium, possess GLP-1 receptors.

It is biologically plausible that therapeutic GLP-1 agonists bind to these receptors and directly influence gut function. This could manifest as changes in the production of antimicrobial peptides, alterations in the mucus layer that serves as the primary habitat for microbes, or modulation of local immune responses.

This line of research is still developing, yet it points toward a sophisticated biological dialogue where the medication, the gut lining, and the microbiome are all in constant communication, working together to regulate metabolic health.

Academic

A systems-biology perspective reveals the relationship between GLP-1 receptor agonists Meaning ∞ GLP-1 Receptor Agonists are a class of pharmacological agents mimicking glucagon-like peptide-1, a natural incretin hormone. and the gut microbiome as a sophisticated, bidirectional feedback loop. The gut microbiota is not merely a passive recipient of altered nutrient flow; it is an active endocrine organ that produces metabolites and signals that influence host physiology, including the secretion of native GLP-1.

For example, the fermentation of dietary prebiotics by specific bacteria produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, propionate, and acetate. These molecules serve as signaling agents that bind to G-protein coupled receptors (e.g. GPR41, GPR43) on enteroendocrine L-cells, directly stimulating the release of GLP-1 and Peptide YY (PYY).

This establishes a baseline of interaction where the microbiome tunes the host’s incretin response. The introduction of a pharmacological GLP-1 agonist powerfully enters this existing dialogue, creating a new equilibrium.

The administration of GLP-1 agonists initiates a therapeutic cycle, where the drug modulates the microbiome, and the resulting microbial shifts reinforce the drug’s metabolic benefits.

The therapeutic intervention can be seen as amplifying one side of the conversation, which in turn reshapes the other. The agonist provides a strong, consistent GLP-1 signal, leading to systemic metabolic improvements. These improvements, coupled with changes in digestive transit and nutrient availability, cultivate a microbial community that is itself more conducive to metabolic health.

This new community may even become more efficient at producing the very SCFAs that support endogenous GLP-1 production, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of metabolic regulation. This perspective reframes the action of GLP-1 agonists from a simple hormonal replacement to a strategic modulation of a complex host-microbe system.

How Does This Interaction Mitigate Metabolic Endotoxemia?

One of the most clinically significant consequences of this interaction is the mitigation of metabolic endotoxemia. The chronic, low-grade inflammation that drives insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease is often initiated in the gut. In a dysbiotic state, particularly one associated with a high-fat diet, the gut barrier can become compromised, a condition often described as increased intestinal permeability.

This allows inflammatory components of gut bacteria, most notably lipopolysaccharides (LPS), to translocate from the gut lumen into the systemic circulation. LPS, a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, is a potent trigger of the innate immune system via Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). Its presence in the bloodstream, or endotoxemia, instigates a systemic inflammatory cascade that directly impairs insulin signaling in muscle, liver, and adipose tissue.

GLP-1 receptor agonists combat this process at multiple levels. First, by promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria like Akkermansia muciniphila Meaning ∞ Akkermansia muciniphila is a specific bacterial species residing within the human gut microbiota. and various Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species, they directly support the health of the gut barrier. A. muciniphila enhances the mucus layer and promotes the expression of tight junction proteins that “seal” the gaps between intestinal cells.

Second, these agonists often lead to a reduction in the relative abundance of Proteobacteria, a phylum of Gram-negative bacteria that includes many LPS-producing species. The combined effect is a fortified gut barrier and a reduced luminal concentration of inflammatory triggers.

This significantly lowers the translocation of LPS into the bloodstream, thereby reducing the inflammatory burden on the entire system and improving insulin sensitivity. The alteration of the microbiome is therefore a primary mechanism through which GLP-1 agonists exert their profound anti-inflammatory and metabolic effects.

The following list outlines key mechanisms in this process:

- Fortification of the Gut Barrier ∞ Increased abundance of species like Akkermansia muciniphila enhances the intestinal mucus layer and tight junction integrity, reducing permeability.

- Reduction of Inflammatory Load ∞ The microbial community shifts away from Gram-negative, LPS-producing bacteria, lowering the primary source of endotoxins.

- Production of Beneficial Metabolites ∞ The promotion of SCFA-producing bacteria yields molecules like butyrate, which serves as a fuel source for colonocytes and has direct anti-inflammatory properties.

- Modulation of Local Immunity ∞ Direct action of GLP-1 agonists on receptors in the gut may temper local inflammatory responses within the intestinal lining itself.

Challenges and Future Research Directions

Despite these significant insights, the field is still in its nascent stages. The translation of findings from animal models to human populations requires careful consideration of the vast differences in physiology and environmental exposures. The table below outlines some of the key challenges and the corresponding future research needed to build a more complete and actionable understanding of this complex interaction.

| Challenge | Future Research Direction |

|---|---|

| Inter-individual Variability |

Longitudinal studies that correlate baseline microbiome composition with therapeutic response to identify microbial biomarkers that predict success or side effects. |

| Dietary Confounding |

Clinical trials with tightly controlled dietary interventions to isolate the direct effects of the medication from changes in eating habits. |

| Long-Term Effects |

Multi-year observational studies and extension trials to determine if the microbial shifts are sustained over time and how they evolve with prolonged therapy. |

| Mechanistic Uncertainty |

Use of multi-omics approaches (metagenomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics) to map the precise functional changes in the microbiome and host response. |

| Standardization of Methods |

Development of consensus guidelines for sample collection, sequencing, and data analysis to ensure results are comparable across different studies. |

References

- Gofron, K. K. Wasilewski, A. and Malgorzewicz, S. “Effects of GLP-1 Analogues and Agonists on the Gut Microbiota ∞ A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 25, no. 8, 2024, p. 4149.

- Wang, Li, et al. “A Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Lowers Weight by Modulating the Structure of Gut Microbiota.” Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, vol. 8, 2018.

- Cani, Patrice D. and Nathalie M. Delzenne. “Gut microbiota and GLP-1.” ResearchGate, 2018.

- “GLP-1 agonists may reshape the gut microbiome.” News-Medical.net, 11 Apr. 2024.

- “The GLP-1 boom ∞ Rising usage and its impact on the microbiome.” Nutritional Outlook, 23 May 2024.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Internal Ecosystem

The knowledge that a therapeutic intervention actively reshapes your internal microbial world presents a profound opportunity for partnership with your own body. You are not merely a passive recipient of a medication’s effects; you are the steward of the ecosystem in which it operates.

The food you eat, the exercise you undertake, and the lifestyle you lead are powerful inputs that can either amplify or dampen the beneficial microbial shifts initiated by a GLP-1 agonist. How might an understanding of your gut as a responsive, living garden change your approach to daily wellness?

This journey is about reclaiming vitality through a sophisticated recalibration of your biology. The information presented here is a map. The path forward is yours to walk, informed by a deeper awareness of the intricate, living systems that define your health.