Fundamentals

You’ve noticed the changes. Perhaps it’s a subtle thinning at the crown, or a receding hairline that seems to have a mind of its own. You’ve done the research, and the term “DHT blocker” has surfaced as a primary line of defense.

This leads to a critical and deeply personal question ∞ will it work for you? The experience of watching your hair change can feel isolating, a silent conversation with the mirror. It is a biological process, one written into your cells long before you were aware of it. The path forward begins with understanding that your body’s response to any therapeutic protocol is a direct conversation with your unique genetic blueprint.

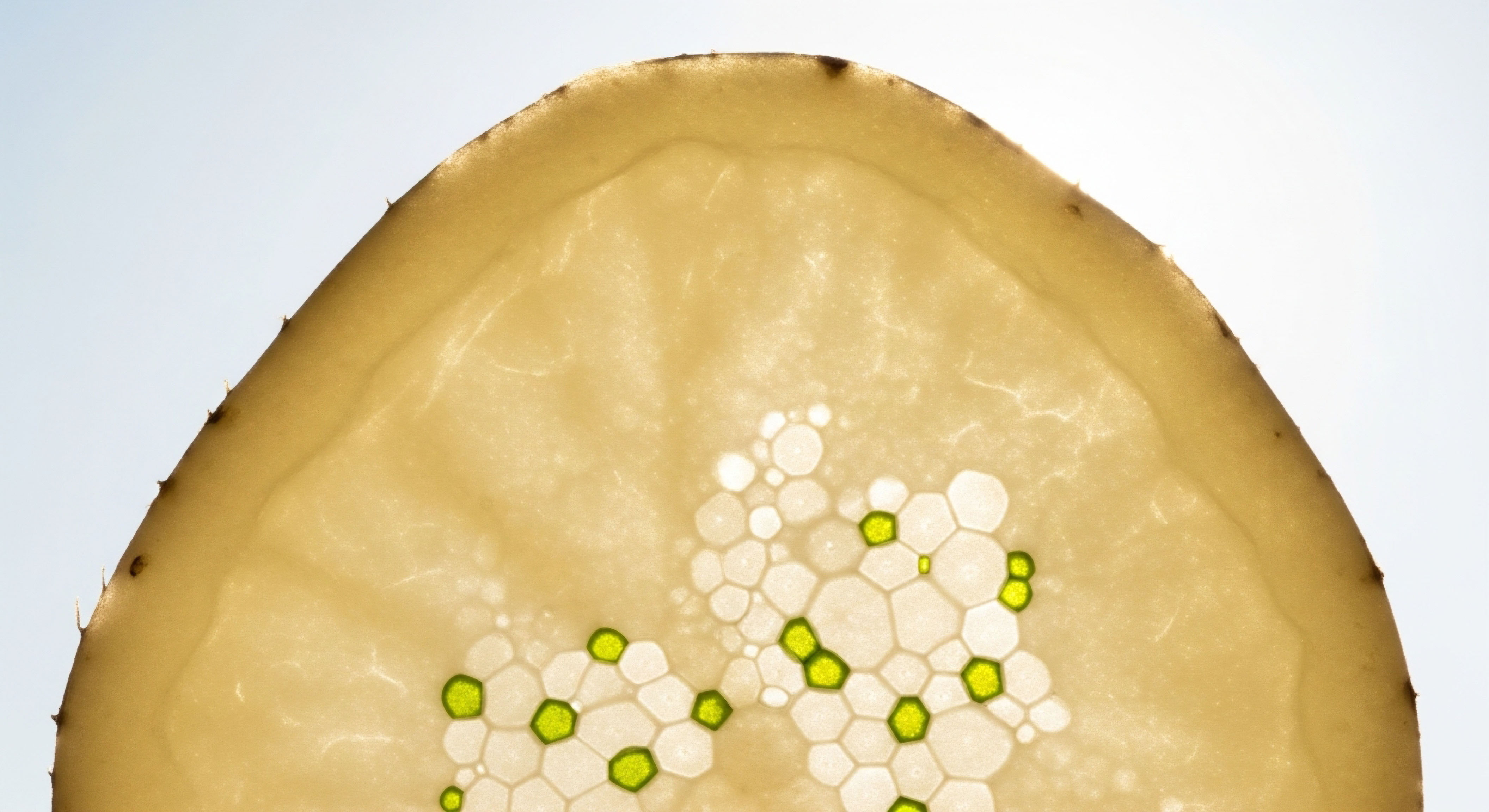

At the heart of male pattern hair loss, or androgenetic alopecia, is a powerful hormone called dihydrotestosterone (DHT). This molecule is a more potent derivative of testosterone, synthesized by an enzyme known as 5-alpha reductase (5AR). In individuals with a genetic predisposition, hair follicles on the scalp become exquisitely sensitive to DHT.

The hormone binds to androgen receptors in these follicles, initiating a process called miniaturization. Over time, this causes the hair-producing cycle to shorten and the follicles to shrink, resulting in progressively finer, shorter hairs until growth ceases entirely.

DHT blockers, such as finasteride and dutasteride, function by inhibiting the 5AR enzyme, thereby reducing the amount of testosterone that gets converted into DHT. This intervention is designed to protect the follicles from the miniaturizing effects of DHT, slowing hair loss and, in some cases, promoting regrowth.

Your genetic makeup fundamentally dictates how your body metabolizes hormones and medications, shaping your individual response to DHT blocker therapy.

The core of the issue lies in the fact that this entire process, from testosterone conversion to follicular sensitivity, is governed by your genes. These are the operating instructions for your body’s complex biochemical machinery. Variations in these instructions explain why one person may see significant results from a DHT blocker, while another may experience a more modest outcome.

It is a matter of biochemical individuality. Your system is not a generic model; it is a highly specific, personalized ecosystem. Therefore, predicting your response to a therapy like DHT blocking requires looking at the genetic code that directs these hormonal pathways.

This is where the science of pharmacogenomics comes into play, offering a window into how your specific genetic variants might influence the effectiveness of these treatments. The journey to understanding your hair loss is intertwined with the journey of understanding your own unique biology.

Intermediate

To appreciate how genetics can forecast the efficacy of DHT blocker therapy, we must first examine the specific mechanisms at play. The primary targets of these medications are the 5-alpha reductase enzymes, which exist in different forms, or isoenzymes. Your genetic code dictates the structure and activity level of these enzymes. This genetic variability is a key determinant of how much DHT your body produces and, consequently, how well a drug designed to inhibit this production will work.

The Role of 5-Alpha Reductase Isoenzymes

There are two principal types of the 5-alpha reductase enzyme that are relevant to androgenetic alopecia ∞ Type I and Type II. Finasteride primarily inhibits the Type II isoenzyme, which is abundant in the hair follicles of the scalp. Dutasteride, on the other hand, is a dual inhibitor, blocking both Type I and Type II 5AR.

This broader action is why dutasteride can lower systemic DHT levels more significantly than finasteride. However, the relative activity of these two isoenzymes can vary from person to person, a difference that is rooted in genetics. If an individual has a particularly active Type I 5AR pathway, they might find that a dual inhibitor like dutasteride offers a more robust response compared to a selective Type II inhibitor.

Genetic variations, known as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), within the genes that code for these enzymes (SRD5A1 for Type I and SRD5A2 for Type II) can influence their efficiency. For instance, a specific SNP might result in a more active enzyme, leading to higher baseline DHT levels.

In such a case, a potent DHT blocker would be necessary to achieve a clinically significant reduction in DHT and a visible improvement in hair density. Conversely, someone with a less active variant of the enzyme might respond well to a lower dose or a less potent inhibitor.

Androgen Receptor Sensitivity a Key Genetic Factor

The other side of the equation is the androgen receptor (AR) itself. The gene for the AR is located on the X chromosome, and variations in this gene can determine the sensitivity of hair follicles to DHT. Even with normal or low levels of DHT, a highly sensitive androgen receptor can trigger the miniaturization process.

Polymorphisms in the AR gene have been strongly linked to the risk and severity of male pattern baldness. These genetic markers can help predict not just the likelihood of developing hair loss, but also the potential responsiveness to a therapy that lowers DHT levels.

If the receptors are exceptionally sensitive, even a substantial reduction in DHT might not be enough to halt the progression of hair loss completely. This is a critical piece of the predictive puzzle. A person’s genetic profile can offer clues as to whether the primary issue is excessive DHT production, heightened receptor sensitivity, or a combination of both.

Variations in the genes for both the 5-alpha reductase enzymes and the androgen receptor are the primary drivers of differing responses to DHT blockers.

Understanding these genetic nuances allows for a more personalized approach to treatment. It moves the conversation beyond a one-size-fits-all protocol and toward a strategy that is tailored to an individual’s unique biochemical landscape. The table below outlines some of the key genetic factors and their potential influence on treatment outcomes.

| Genetic Factor | Gene(s) Involved | Potential Impact on Treatment Response |

|---|---|---|

| 5-Alpha Reductase Activity | SRD5A1, SRD5A2 | Higher enzyme activity may necessitate a more potent or dual inhibitor like dutasteride for an effective response. |

| Androgen Receptor Sensitivity | AR | Increased receptor sensitivity can diminish the effects of DHT reduction, potentially requiring combination therapies. |

| Hormone Metabolism Pathways | CYP Genes, UGT Genes | Variations can affect how quickly the body metabolizes and clears DHT blockers, influencing optimal dosage and frequency. |

| Estrogen Synthesis | CYP19A1 (Aromatase) | Alterations in the testosterone-to-estrogen conversion pathway can indirectly affect androgen balance and treatment outcomes. |

Ultimately, the effectiveness of a DHT blocker is the result of a complex interplay between the drug’s mechanism of action and an individual’s unique genetic predispositions. By examining these genetic markers, it is possible to move closer to a predictive model of treatment response, allowing for more informed decisions and better-managed expectations on the journey to reclaiming hair health.

Academic

A sophisticated understanding of predicting response to DHT blocker therapy requires a deep dive into the complex world of pharmacogenomics and the intricate metabolic pathways that govern androgen activity. The clinical observation that individuals exhibit varied responses to finasteride and dutasteride is not a matter of chance; it is a direct reflection of their unique genetic architecture.

Recent research has begun to identify specific genetic loci that are statistically associated with these differential outcomes, moving us toward a more precise and personalized approach to androgenetic alopecia management.

Genetic Variants beyond SRD5A and AR

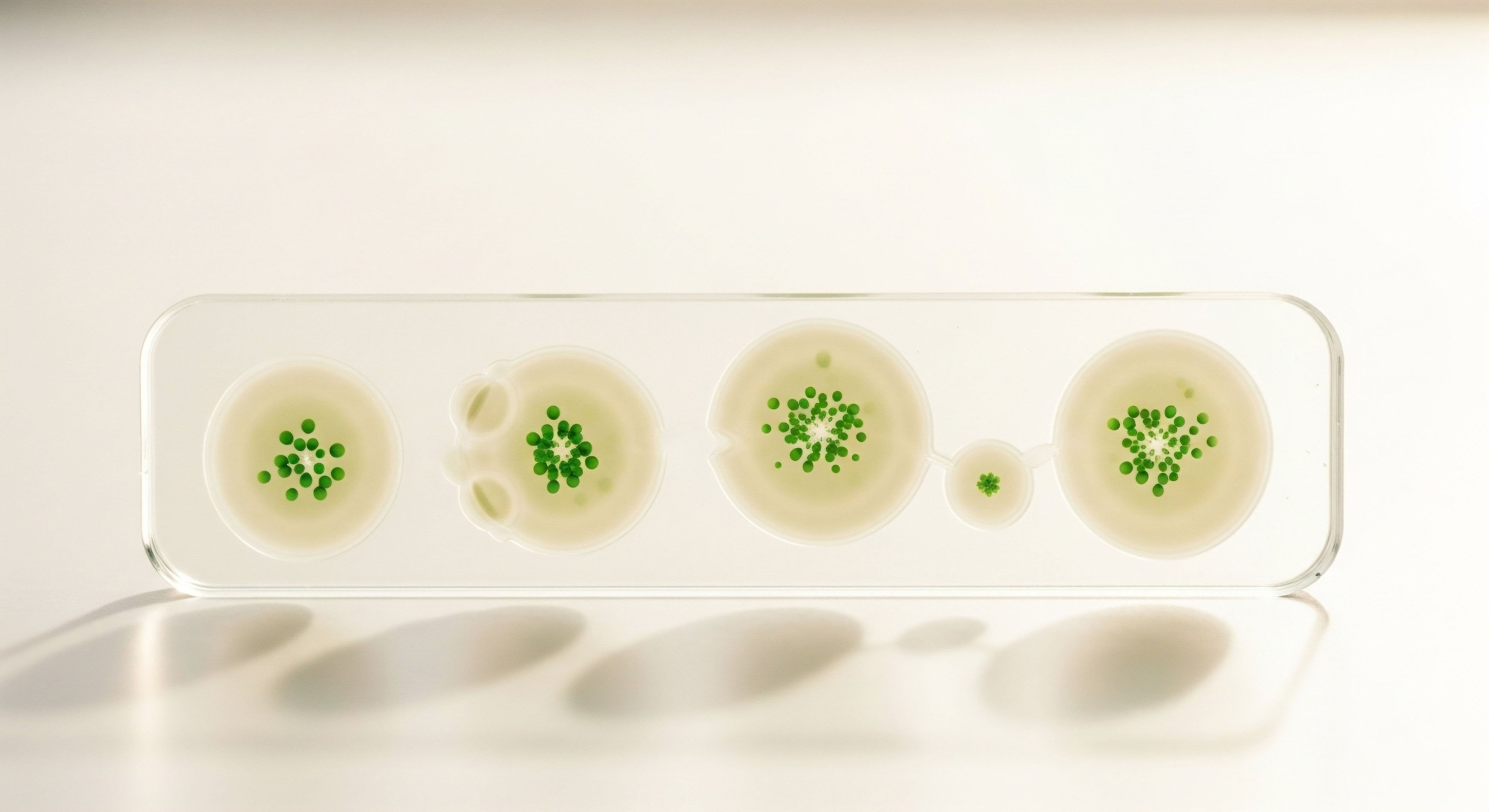

While the genes for the 5-alpha reductase enzymes (SRD5A1, SRD5A2) and the androgen receptor (AR) are foundational to the pathophysiology of hair loss, they are not the sole determinants of therapeutic success. A 2019 study published in PLOS ONE identified several other candidate genes that appear to influence the response to dutasteride.

The study pinpointed a synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), rs72623193, in the gene DHRS9 as being most significantly associated with dutasteride response. DHRS9 is involved in the metabolic pathways of steroids, and this finding suggests that alternative routes of androgen synthesis and metabolism, sometimes referred to as “backdoor pathways,” may play a more significant role than previously appreciated.

Even when the primary 5AR pathway is inhibited, genetic variations that upregulate these alternative pathways could potentially limit the overall reduction in follicular DHT, thereby dampening the therapeutic effect.

The same study also highlighted a non-synonymous SNP, rs2241057, in the gene CYP26B1. The CYP family of enzymes is critical for the metabolism of a wide range of compounds, including hormones and drugs. A variation in a CYP enzyme could influence the pharmacokinetics of dutasteride, affecting how the drug is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted.

This could alter the drug’s bioavailability and half-life, meaning that individuals with certain CYP variants might require different dosing strategies to achieve the same therapeutic concentration of the drug at the target tissue. Furthermore, the study suggested that variants in genes like ESR1 (Estrogen Receptor 1) and CYP19A1 (Aromatase) are also associated with response.

This underscores the interconnectedness of the endocrine system; the balance between androgens and estrogens is a delicate one, and genetic factors that shift this balance can have downstream effects on hair follicle health and response to therapy.

What Are the Implications of a Cumulative Genetic Score?

The future of predictive modeling for DHT blocker response likely lies in the development of a polygenic risk score. This would involve analyzing a panel of relevant SNPs across multiple genes and calculating a cumulative score that predicts an individual’s likely response.

The study on dutasteride response demonstrated that the cumulative effect of multiple SNPs, presented in both additive and non-additive models, was a powerful predictor of outcome. This approach acknowledges that complex traits like drug response are rarely governed by a single gene. They are the result of a network of genetic influences, each contributing a small effect. By integrating data from multiple genetic loci, a more nuanced and accurate prediction can be made.

The identification of specific genetic variants in genes like DHRS9 and CYP26B1 provides a more granular understanding of why individuals respond differently to DHT blocker therapy.

This level of genetic insight has profound implications for clinical practice. It could allow clinicians to stratify patients into likely “good responders” and “poor responders” before initiating therapy. For a predicted poor responder, a more aggressive initial approach, such as starting with dutasteride instead of finasteride, or counseling on the likelihood of needing adjunctive therapies, could be considered.

For a predicted good responder, it could provide reassurance and encourage adherence to the treatment plan. The table below summarizes some of the key genes and their functions in this complex predictive model.

| Gene | Function | Relevance to Treatment Response |

|---|---|---|

| DHRS9 | Dehydrogenase/Reductase Family Member 9 | Involved in steroid metabolism. Variants may influence alternative androgen pathways, affecting DHT levels even when 5AR is inhibited. |

| CYP26B1 | Cytochrome P450 Family 26 Subfamily B Member 1 | Metabolizes retinoic acid and other molecules. Variants could alter drug metabolism and bioavailability. |

| ESR1 | Estrogen Receptor 1 | Mediates the effects of estrogen. Variations can impact the overall androgen/estrogen balance in the scalp. |

| SRD5A1 | Steroid 5-Alpha-Reductase 1 | Target of dutasteride. Variants can directly influence the drug’s effectiveness. |

The journey toward fully personalized medicine in the realm of hormonal health is well underway. As our understanding of the genetic architecture of drug response continues to grow, we move closer to a future where treatment decisions are guided by an individual’s unique biological code, maximizing efficacy and minimizing the uncertainty that so often accompanies the start of a new therapeutic protocol.

It is also important to consider the limitations of current research. Many of these studies are conducted on specific populations, and the prevalence of certain genetic variants can differ between ethnic groups. Therefore, more diverse and large-scale studies are needed to validate these findings and develop predictive models that are applicable to a global population.

The field is rapidly evolving, and the integration of this genetic data into clinical decision-making will be a key step forward in the management of androgenetic alopecia.

- Androgenetic Alopecia A common form of hair loss in both men and women. In men, this condition is also known as male-pattern baldness.

- Pharmacogenomics The study of how genes affect a person’s response to drugs.

- Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) A variation in a single nucleotide that occurs at a specific position in the genome.

References

- Hillmer, A. M. et al. “Genetic variation in the human androgen receptor gene is the major determinant of common early-onset androgenetic alopecia.” The American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 77, no. 1, 2005, pp. 140-148.

- Lee, Won-Soo, et al. “Genetic variations associated with response to dutasteride in the treatment of male subjects with androgenetic alopecia.” PLoS ONE, vol. 14, no. 9, 2019, e0222533.

- Bang, H. J. et al. “The role of the 5α-reductase and androgen receptor genes in male androgenetic alopecia.” Annals of Dermatology, vol. 24, no. 3, 2012, pp. 299-305.

- Cobb, J. E. et al. “Genetic variants in the 5α-reductase type II (SRD5A2) gene are not associated with female pattern hair loss.” British Journal of Dermatology, vol. 162, no. 3, 2010, pp. 684-686.

- Kaufman, K. D. et al. “Finasteride in the treatment of men with androgenetic alopecia.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, vol. 39, no. 4, 1998, pp. 578-589.

Reflection

Your Personal Health Equation

The information presented here offers a glimpse into the intricate biological systems that define your health. The science of genetics provides a powerful lens through which to view your body, revealing the subtle yet significant variations that make your experience entirely your own.

The knowledge that your response to a therapy is written in your DNA can be profoundly empowering. It shifts the focus from a passive hope for results to an active engagement with your own health narrative. This understanding is the first step on a path toward personalized wellness, a journey where clinical data and personal experience converge.

The path forward is one of partnership with your own biology, a process of learning its language and providing the specific support it needs to function optimally. What will your next step be in this personal exploration of your health?

Glossary

dht blocker

androgenetic alopecia

5-alpha reductase

dutasteride

finasteride

genetic variants

pharmacogenomics

5-alpha reductase enzymes

dual inhibitor like dutasteride

srd5a2

androgen receptor

hair loss

receptor sensitivity

single nucleotide polymorphism

dhrs9

cyp26b1