Fundamentals

You have likely encountered a confusing whirlwind of information regarding hormone therapy and its relationship with the heart. One moment, you hear whispers of its protective qualities; the next, you are met with stark warnings of risk. This feeling of uncertainty is entirely valid.

It stems from a conversation that has been evolving for decades, shaped by landmark studies and their subsequent re-evaluations. Your personal health journey requires clarity, and that begins with understanding your own biological systems. The question of how hormonal therapy influences cardiovascular risk is answered by looking at the intricate communication network within your body and how that network changes over time.

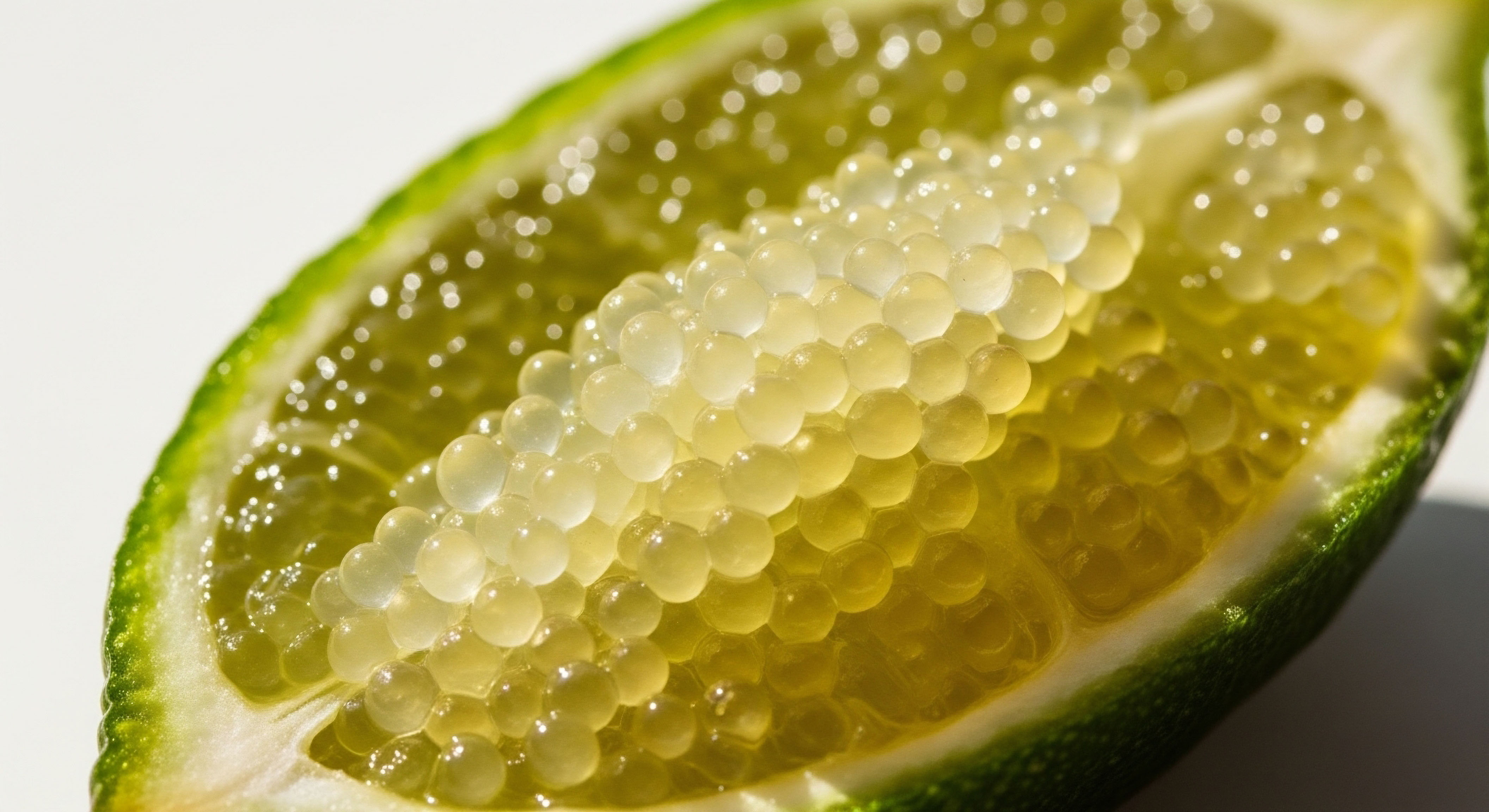

Think of your cardiovascular system, your heart and blood vessels, as a dynamic, living ecosystem. Before menopause, this system operates in an environment rich with estrogen. This primary female hormone performs a multitude of functions that support cardiovascular wellness.

It helps maintain the flexibility and resilience of your blood vessel walls, much like a skilled caretaker tending to a network of vital pathways. Estrogen positively influences the production of substances that allow vessels to relax and widen, ensuring smooth blood flow. It also plays a supportive role in managing cholesterol levels, helping to maintain a favorable balance between different lipid particles circulating in your bloodstream. This hormonal environment is a key contributor to cardiovascular protection during your reproductive years.

The transition into menopause marks a profound shift in this internal environment. The decline in ovarian estrogen production changes the signals being sent to your blood vessels, heart, and liver. This is a natural biological process, a programmed recalibration of your endocrine system. Without the same high levels of estrogen, blood vessels may gradually become stiffer.

The balance of lipids can shift, and the body’s inflammatory response may change. It is within this new biological context that the conversation about hormone therapy begins. The core purpose of hormonal optimization protocols is to reintroduce some of these key messengers, aiming to support the body’s systems through this transition and alleviate the symptoms that arise from it.

The influence of female hormone therapy on cardiovascular health is a complex interplay between the timing of its initiation, the specific types of hormones used, and an individual’s unique physiology.

The Three Pillars of Cardiovascular Consideration

To move past the confusing headlines, we must reframe the question. We ask what specific factors determine the cardiovascular effect of hormone therapy in any given individual. The scientific and clinical evidence points to three foundational pillars that govern this relationship. Understanding these pillars provides a framework for making informed, personalized decisions in partnership with a knowledgeable clinician.

- The Pillar of Timing. When therapy is initiated is perhaps the most significant factor. There is a critical window of opportunity. Starting hormone therapy near the onset of menopause has a very different impact on the cardiovascular system compared to starting it a decade or more later. The health and condition of the blood vessels at the time therapy begins are paramount.

- The Pillar of Type. Hormones are not all created equal. The molecular structure of a hormone determines how it interacts with receptors throughout the body. There are meaningful differences between bioidentical hormones, like micronized progesterone and estradiol, and synthetic versions, such as medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) and conjugated equine estrogens (CEE). Furthermore, the method of delivery ∞ whether a hormone is taken orally as a pill or absorbed through the skin via a patch, gel, or cream ∞ dramatically alters its effects on the body, particularly on the liver and its production of clotting factors.

- The Pillar of Individuality. Your body is unique. Your genetic predispositions, your existing health status, your lifestyle, and your metabolic health all create a specific biological backdrop. Factors like blood pressure, insulin sensitivity, and baseline inflammatory levels influence how your system will respond to hormonal therapy. A protocol must be tailored to this individual context, which is why a thorough evaluation and ongoing monitoring are essential components of a well-designed therapeutic strategy.

These three pillars form the basis of a modern, evidence-based approach to female hormone therapy. By examining each one, we can begin to assemble a clear, coherent picture of how to support the body’s intricate systems, validating the lived experience of symptoms while providing a logical path toward reclaiming vitality and function. The goal is to understand your own biology so profoundly that you can work with it, not against it.

Intermediate

To truly grasp the nuanced relationship between female hormone therapy and cardiovascular disease risk, we must examine the scientific story that has unfolded over the past several decades. This story is dominated by one major event ∞ the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), a massive set of clinical trials launched in the 1990s.

The initial results, published in the early 2000s, sent shockwaves through the medical community and public consciousness. The trial was stopped early because one arm, which studied the combination of conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) and a synthetic progestin, medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), showed a small but statistically significant increase in the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and blood clots.

This led to a dramatic and swift decline in the prescription of all forms of hormone therapy, leaving millions of women and their doctors in a state of confusion and concern.

However, the initial interpretation of the WHI data told only part of the story. The average age of the women in the trial was 63, with many participants being more than 10 or even 20 years past the onset of menopause. As researchers performed deeper, pre-planned analyses of the data, a critical pattern began to appear.

This pattern is now known as the “timing hypothesis.” It revealed that a woman’s age and her time since menopause were the most important determinants of the cardiovascular effects of hormone therapy. The risks identified in the initial WHI report were concentrated almost entirely in the older participants. Women who began hormone therapy within 10 years of menopause showed very different outcomes.

The Critical Importance of the Timing Hypothesis

The timing hypothesis provides a biological explanation for the differing outcomes observed in the WHI. It suggests that estrogen has beneficial effects on blood vessels that are still relatively healthy and free of significant atherosclerotic plaque, which is more common in younger, newly menopausal women.

In this state, estrogen can help maintain vessel elasticity and reduce inflammation. Conversely, initiating estrogen therapy in older arteries that may already contain established, unstable plaque could have a different effect. It might increase the activity of certain enzymes that could destabilize this existing plaque, potentially leading to a rupture and a subsequent cardiovascular event like a heart attack or stroke.

This distinction is fundamental. The cardiovascular system of a 52-year-old woman who just entered menopause is biologically different from that of a 68-year-old woman who has been postmenopausal for nearly two decades. The following table, based on cumulative data from the WHI trials, illustrates this divergence in outcomes.

| Outcome | Initiation Less Than 10 Years From Menopause (Ages 50-59) | Initiation More Than 20 Years From Menopause (Ages 70-79) |

|---|---|---|

| Coronary Heart Disease |

Showed a trend toward risk reduction or a neutral effect. The absolute risk was very low in this group. |

Demonstrated a statistically significant increase in risk during the initial years of therapy. |

| All-Cause Mortality |

Was associated with a significant reduction in death from all causes, a powerful indicator of overall benefit. |

Showed a neutral or slightly increased trend, with no mortality benefit observed. |

| Stroke |

The risk of stroke, while still present, was lower in absolute terms for this younger age group. |

The risk of stroke was more pronounced in this older cohort. |

How Does the Type and Route of Hormones Matter?

The WHI primarily studied one specific formulation ∞ oral CEE plus MPA. This specific combination is quite different from the bioidentical hormones often used in modern clinical practice. The distinction between hormone types and their delivery route is a central piece of the puzzle. When hormones are taken orally, they undergo “first-pass metabolism” in the liver.

This process can significantly increase the production of proteins involved in blood clotting (coagulation factors) and certain inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP). This hepatic effect is directly linked to the increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and stroke seen with oral estrogen therapy.

Transdermal hormone delivery, using patches, gels, or creams, largely bypasses this first-pass effect in the liver. Estradiol is absorbed directly into the bloodstream, mimicking the body’s natural release from the ovaries more closely. This route has been consistently shown to have a much more neutral effect on clotting factors and inflammatory markers, resulting in a significantly better safety profile regarding the risk of blood clots and stroke.

Modern hormone therapy protocols prioritize transdermal estradiol and bioidentical progesterone, which have a different and more favorable cardiovascular risk profile than the oral, synthetic hormones used in early landmark trials.

The progestogen component is equally important. The synthetic progestin MPA, used in the WHI, has a different molecular structure and biological activity than the body’s own progesterone. MPA can have some androgenic effects and has been shown to counteract some of the positive effects of estrogen on cholesterol levels, blood pressure, and blood sugar regulation.

In contrast, micronized progesterone, which is structurally identical to the hormone produced by the ovaries, appears to be metabolically neutral. It does not seem to negatively impact lipids or blood pressure and is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer compared to synthetic progestins. Some evidence even suggests it may have calming effects and support sleep, working synergistically with estradiol. The choice of progestogen is a critical variable in designing a safe and effective hormonal optimization protocol.

What about the Role of Testosterone in Women?

The conversation around female hormonal health often centers exclusively on estrogen and progesterone. This overlooks the vital role of a third hormone ∞ testosterone. Women produce testosterone in their ovaries and adrenal glands, and it is essential for maintaining muscle mass, bone density, energy levels, cognitive function, and libido. Testosterone levels decline with age, and this decline can contribute to some of the symptoms attributed to menopause.

From a cardiovascular perspective, maintaining healthy testosterone levels can be beneficial. Testosterone supports lean muscle mass, which improves insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic health. Some studies suggest that appropriately dosed testosterone therapy in postmenopausal women can have positive effects on inflammatory markers associated with cardiovascular disease and may improve body composition without adversely affecting cholesterol levels.

It is crucial to distinguish that these protocols use very low, physiologic doses of testosterone, such as 10-20 units (0.1-0.2ml of a 200mg/ml solution) administered weekly. This is a very different approach from the high doses that could potentially lead to negative metabolic changes. The inclusion of low-dose testosterone in a comprehensive female hormone protocol addresses a wider range of biological systems, aiming for a more complete restoration of endocrine balance and its associated benefits for long-term wellness.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of hormone therapy’s influence on cardiovascular disease (CVD) requires moving beyond population-level statistics into the realm of molecular biology and vascular physiology. The apparent paradoxes presented by clinical trial data, particularly the divergent outcomes of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), are resolved when we examine the specific interactions between different hormonal formulations and the cellular machinery of the cardiovascular system.

The central thesis is that the biological state of the vascular endothelium at the time of therapeutic initiation is the principal determinant of whether exogenous hormones will exert a protective or potentially detrimental effect. This exploration will focus on the cellular mechanisms that underpin the timing hypothesis, the pharmacologic distinctions between hormonal preparations, and the often-underappreciated role of testosterone.

Endothelial Function and the Estrogen Receptor

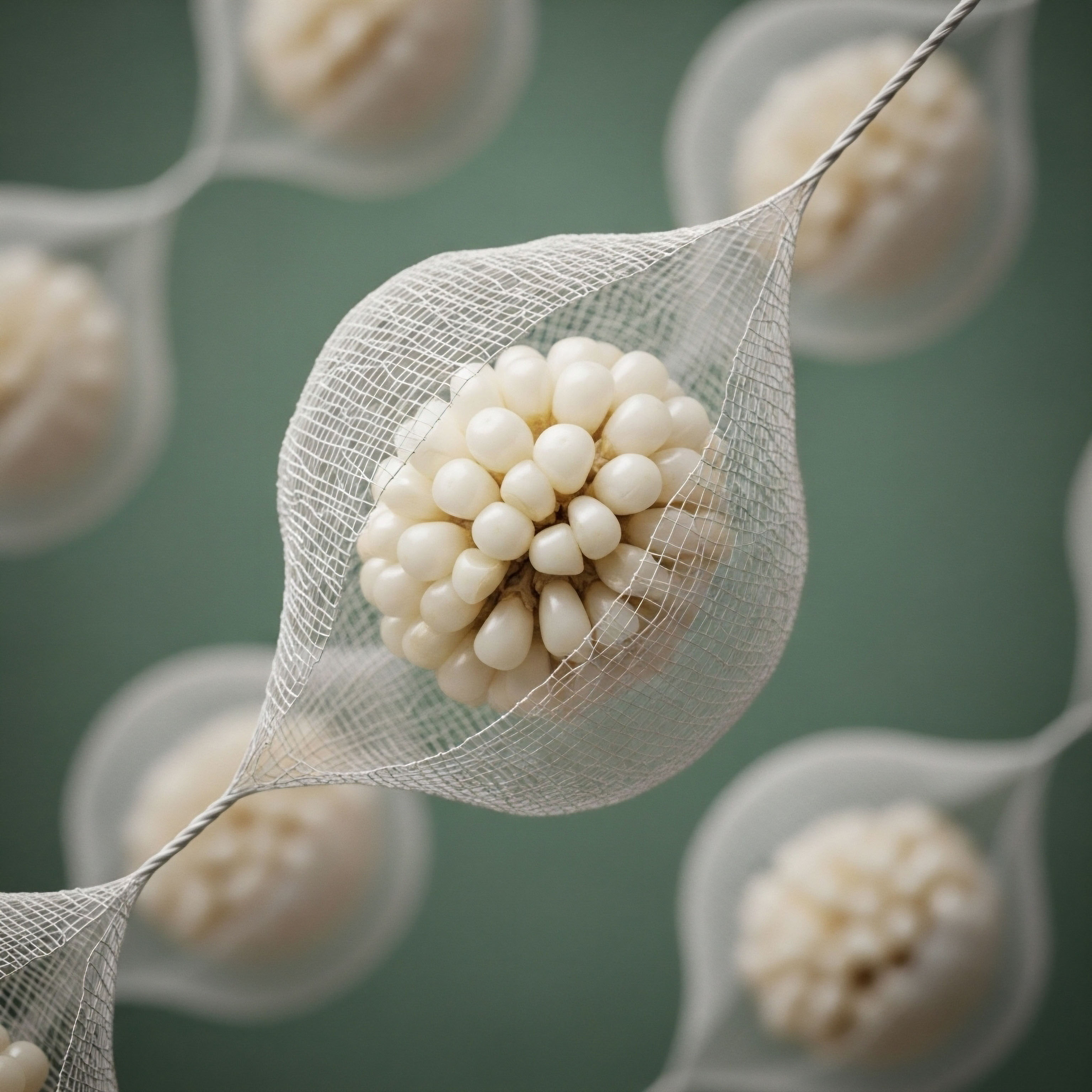

The endothelium, the single layer of cells lining all blood vessels, is a critical regulator of vascular homeostasis. It is exquisitely sensitive to hormonal signaling, primarily through two estrogen receptor subtypes ∞ estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and estrogen receptor beta (ERβ). In a healthy, pre-menopausal state, estradiol binding to these receptors, particularly ERα, triggers a cascade of vasoprotective events.

A key mechanism is the activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), the enzyme responsible for producing nitric oxide (NO). NO is a potent vasodilator and a powerful anti-inflammatory and anti-thrombotic agent.

It inhibits platelet aggregation, smooth muscle cell proliferation, and the expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules on the endothelial surface, which are early steps in the formation of atherosclerotic plaque. Studies consistently show that estradiol administration improves flow-mediated dilation, a direct measure of NO bioavailability and endothelial health.

The aging process and the prolonged absence of estrogen after menopause alter this landscape. The expression and function of estrogen receptors can change, and the underlying vascular environment becomes more pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic. This sets the stage for the development of atherosclerosis.

When hormone therapy is initiated in a younger woman close to menopause (the “timing window”), the still-responsive endothelium can leverage the reintroduced estradiol to restore these protective NO-mediated pathways. However, initiating therapy in an older woman with established, complex atherosclerotic plaques presents a different scenario.

Here, estrogen’s effects on other cellular processes, such as the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), may become dominant. MMPs are enzymes that degrade the extracellular matrix. An acute increase in MMP activity within a vulnerable plaque could theoretically weaken its fibrous cap, increasing the risk of rupture and subsequent thrombosis. This provides a compelling molecular explanation for the increased coronary event rate observed in the first year of the WHI among older participants.

Pharmacokinetics and the Differential Impact on Hemostasis

The formulation and delivery route of hormone therapy create distinct pharmacological profiles with profound implications for hemostasis and thrombosis risk. This is most clearly illustrated by comparing oral conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) with transdermal 17β-estradiol. Oral estrogens are subject to extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver, leading to supraphysiologic intrahepatic hormone concentrations. This metabolic burden significantly alters the liver’s synthesis of a wide array of proteins.

The molecular distinctions between oral and transdermal hormone delivery, particularly their effects on hepatic protein synthesis, are central to understanding their different cardiovascular risk profiles.

The following table details the differential impact of these two common forms of estrogen therapy on key hemostatic and inflammatory factors. The data synthesized here explains the mechanistic basis for the different risk profiles observed in clinical practice and large-scale studies.

| Biomarker | Oral Estrogen (e.g. CEE) | Transdermal Estradiol |

|---|---|---|

| Coagulation Factors (e.g. Factor VII, Fibrinogen) |

Significantly increases hepatic synthesis, creating a more pro-thrombotic state. This is a primary driver of the elevated VTE risk associated with oral therapy. |

Has a minimal to neutral effect on the synthesis of these factors, as it bypasses the initial high-concentration pass through the liver. This results in a much lower VTE risk. |

| Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) |

Dramatically increases production. This leads to more testosterone and free estradiol being bound and inactivated, reducing their bioavailability and biological activity. |

Causes only a modest or no increase in SHBG, preserving higher levels of free, active hormones, including testosterone. |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) |

Markedly increases levels of this key inflammatory marker, which is synthesized in the liver. This reflects a pro-inflammatory hepatic response. |

Does not increase CRP levels and in some cases may be associated with a decrease, reflecting a more favorable systemic inflammatory profile. |

| Triglycerides |

Tends to increase triglyceride levels due to its effects on hepatic lipid metabolism. |

Has a neutral or even slightly favorable effect, often leading to a reduction in triglyceride levels. |

What Is the Molecular Rationale for Progestogen Selection?

The choice of progestogen is a critical variable that can either complement or antagonize the cardiovascular benefits of estrogen. Synthetic progestins, particularly those derived from testosterone like medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), possess a broader receptor-binding profile. MPA can bind to and activate androgen and glucocorticoid receptors in addition to progesterone receptors.

Its androgenic activity can partially negate estrogen’s beneficial effects on lipid profiles, particularly by lowering HDL cholesterol. Its glucocorticoid activity can negatively impact glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. These “off-target” effects contribute to a less favorable overall metabolic and cardiovascular profile.

Micronized progesterone, being bioidentical to the endogenous hormone, exhibits high specificity for the progesterone receptor. It lacks the androgenic and glucocorticoid activities of many synthetic progestins. Consequently, it does not appear to adversely affect lipid profiles, blood pressure, or endothelial function when co-administered with estrogen.

Data from the French E3N cohort study suggested that hormone regimens containing micronized progesterone were associated with a more favorable risk profile for both breast cancer and cardiovascular events compared to regimens using synthetic progestins. While observational, this data aligns with the known molecular differences and supports the prioritization of micronized progesterone in modern hormonal protocols to maximize safety and efficacy.

- Micronized Progesterone ∞ This bioidentical hormone acts specifically on progesterone receptors. Clinical evidence suggests it maintains a neutral or even favorable profile regarding blood pressure, lipid metabolism, and vascular inflammation. Its use is associated with a lower risk of adverse events compared to synthetic alternatives.

- Synthetic Progestins (e.g. MPA) ∞ These molecules can have broader effects, binding to androgen and glucocorticoid receptors. This can lead to unwanted metabolic consequences, such as negative shifts in cholesterol profiles and impaired glucose tolerance, which may counteract some of estrogen’s cardiovascular benefits.

- Clinical Implication ∞ The selection of the progestogen component is a key point of therapeutic intervention. The evidence strongly supports the use of micronized progesterone to ensure endometrial safety without introducing the potentially negative cardiovascular and metabolic effects associated with many synthetic progestins.

References

- Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. “Risks and Benefits of Estrogen Plus Progestin in Healthy Postmenopausal Women ∞ Principal Results From the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial.” JAMA, vol. 288, no. 3, 2002, pp. 321-33.

- Boardman, H. M. et al. “Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 3, 2015, CD002229.

- Rossouw, J. E. et al. “Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease by Age and Years Since Menopause.” JAMA, vol. 297, no. 13, 2007, pp. 1465-77.

- Stanczyk, F. Z. et al. “Estrogens and progestogens ∞ comparison of oral and transdermal delivery.” Journal of the North American Menopause Society, vol. 18, no. 6, 2011, pp. 624-30.

- Canonico, M. et al. “Hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women ∞ impact of different regimens. The E3N study.” Circulation, vol. 115, no. 7, 2007, pp. 840-5.

- Glaser, R. and Dimitrakakis, C. “Testosterone pellet implants and their use in women.” Maturitas, vol. 74, no. 3, 2013, pp. 209-14.

- Asi, N. et al. “Progesterone vs. synthetic progestins and the risk of breast cancer ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Systematic Reviews, vol. 5, no. 1, 2016, p. 121.

- Manson, J. E. et al. “Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Long-term All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality ∞ The Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trials.” JAMA, vol. 318, no. 10, 2017, pp. 927-38.

- Worboys, S. et al. “Evidence that parenteral testosterone replacement therapy in women has a different safety profile to oral administration.” European Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 148, no. 5, 2003, pp. 509-13.

Reflection

You have now journeyed through the complex science connecting the endocrine system to cardiovascular health. You have seen how the narrative has shifted from one of simple answers to one of sophisticated, personalized understanding. The information presented here is a map, detailing the biological terrain of menopause and the tools available to navigate it. It is designed to replace confusion with a deep, foundational knowledge of your own body’s inner workings.

This knowledge is the first, most crucial step. The next is introspection. How does this information connect with your own lived experience? What are your personal health goals, not just for the next year, but for the decades to come? Do you seek to resolve specific symptoms, or are you focused on a long-term strategy for vitality and resilient aging? Your answers to these questions are unique to you. They form the basis of a truly personalized health strategy.

This journey is best undertaken with a trusted clinical guide, one who can help you interpret your body’s signals and lab results in the context of this scientific framework. The ultimate goal is to move forward with confidence, armed with the understanding that you can be an active, informed participant in your own health. The potential to recalibrate your system and function with renewed vitality is within reach, grounded in a partnership between your personal goals and sound clinical science.