Fundamentals

You feel it in your body. The persistent fatigue, the unpredictable cycles, the frustrating changes in your skin or weight. These experiences are valid, and they are signals from a biological system working hard to find its equilibrium. When we discuss Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), we are talking about a complex endocrine and metabolic condition.

Your body, an intricate network of communication, is operating under a specific set of rules that lead to the symptoms you are experiencing. The question of whether physical movement can, by itself, rewrite those rules is a profound one. It speaks to a desire to reclaim agency over your own physiology, using your own body as the instrument of its healing.

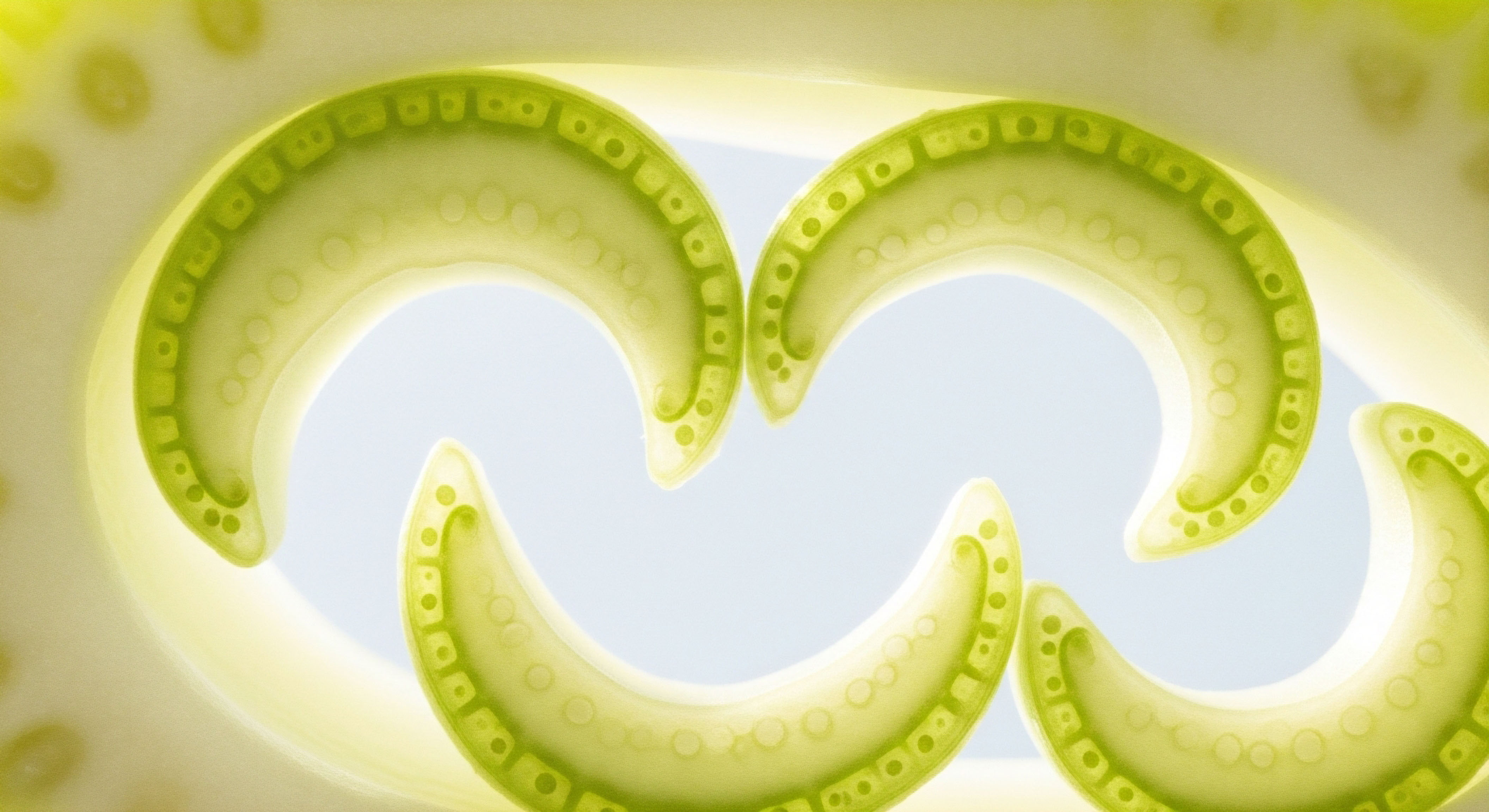

The journey begins with understanding the language of your biology. PCOS is primarily characterized by a few core systemic imbalances. The first is insulin resistance. Think of insulin as a key that unlocks your cells to allow glucose (sugar) to enter and be used for energy.

With insulin resistance, the locks on your cells become less responsive. Your pancreas, the organ that makes insulin, must then produce much more of it to get the job done. This high level of circulating insulin, a state called hyperinsulinemia, is a powerful chemical messenger that drives many other processes within the body.

It can signal the ovaries to produce more androgens, like testosterone, which contributes to symptoms such as acne and hirsutism. It also promotes fat storage, particularly in the abdominal region, which further amplifies insulin resistance and inflammation.

The Core Biomarkers in PCOS

Biomarkers are the measurable indicators of what is happening inside your biological systems. They are the data points in the story of your health, found in your bloodwork. For PCOS, the key biomarkers reflect the core imbalances:

- Insulin and Glucose ∞ Doctors often use a test called the Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR). This calculation uses your fasting insulin and fasting glucose levels to estimate how effectively your body is using insulin. A higher HOMA-IR value points toward greater insulin resistance.

- Androgens ∞ Levels of total and free testosterone, DHEA-S, and androstenedione are measured. Elevated levels are a hallmark of the hyperandrogenism associated with PCOS.

- Inflammatory Markers ∞ C-reactive protein (CRP) is a common marker of systemic inflammation. Chronic low-grade inflammation is a feature of PCOS, contributing to the long-term health risks associated with the condition.

Exercise enters this picture as a powerful biological stimulus. When you engage in physical activity, particularly structured and intentional exercise, you are sending a cascade of signals throughout your body. These signals have the capacity to directly influence the core dysregulations of PCOS.

Your muscles, when they contract, begin to function like a separate endocrine organ, releasing their own signaling molecules. This is the biological foundation for how movement can begin to reverse the biomarker dysregulation you see on a lab report and feel in your daily life.

Exercise acts as a direct biochemical input, capable of recalibrating the cellular signaling pathways that are disrupted in PCOS.

Understanding this connection is the first step. It shifts the perspective from simply managing symptoms to actively participating in the restoration of your body’s internal communication network. The path forward involves learning how to use movement to speak your body’s language, encouraging it back toward a state of metabolic and hormonal health.

Intermediate

To appreciate how exercise influences PCOS biomarkers, we must examine the specific mechanisms of action. Physical movement is a systems-wide event, initiating changes in muscle, adipose tissue, and the liver that collectively counter the condition’s primary drivers. The effectiveness of exercise is tied directly to the type, intensity, and consistency of the activity performed. Different forms of exercise elicit distinct physiological responses, allowing for a tailored approach to addressing specific biomarkers.

How Does Exercise Retune Insulin Sensitivity?

The most critical impact of exercise in the context of PCOS is its ability to improve insulin sensitivity. This occurs through two primary pathways. First, during and immediately after exercise, your muscles can take up glucose from the bloodstream without needing insulin at all.

This is a powerful, non-insulin-dependent pathway for glucose disposal that helps lower blood sugar and reduces the immediate need for high insulin levels. Second, consistent exercise training leads to long-term adaptations within the muscle cells. Your cells increase the number of GLUT4 transporters, the very “gates” that allow glucose to enter.

This means that even when you are at rest, your muscles become more sensitive to insulin’s signal, so your pancreas does not have to work as hard. The result is a lower fasting insulin level and a corresponding improvement in your HOMA-IR score.

Research has shown that the intensity of the exercise plays a significant role. Vigorous-intensity exercise, such as high-intensity interval training (HIIT) or strenuous aerobic activity, appears to produce the most substantial reductions in HOMA-IR. This is likely because higher intensity work places a greater demand on muscle energy stores, triggering more potent signaling for glucose uptake and cellular adaptation.

Comparing Exercise Modalities for PCOS

While any movement is beneficial, structuring an exercise program around specific goals can optimize results. Aerobic exercise and resistance training offer unique and complementary benefits for women with PCOS.

| Biomarker | Aerobic Exercise (e.g. Running, Cycling) | Resistance Training (e.g. Weightlifting) |

|---|---|---|

| HOMA-IR (Insulin Resistance) | Significant improvement, especially with vigorous intensity. Enhances cardiovascular fitness (VO2peak). | Potent improvements. Increases muscle mass, which acts as a larger sink for glucose disposal. |

| C-Reactive Protein (Inflammation) | Shown to effectively lower CRP levels, particularly in women over 30. | Contributes to lower inflammation by improving body composition and releasing anti-inflammatory signals from muscle. |

| Androgen Levels (e.g. Testosterone) | Effects can be variable. Improvements are often secondary to reductions in insulin levels and body fat. | May help improve the Free Androgen Index (FAI) by increasing sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), which binds to testosterone. |

| Body Composition (Waist Circumference) | Effective at reducing waist circumference, a key indicator of visceral fat. | Excellent for building lean muscle mass and improving the muscle-to-fat ratio. |

Vigorous intensity exercise demonstrates a superior capacity for improving cardiorespiratory fitness and reducing insulin resistance in women with PCOS.

The Impact on Inflammation and Hormones

Chronic low-grade inflammation is a self-perpetuating cycle in PCOS, where insulin resistance drives inflammation, and inflammation worsens insulin resistance. Exercise breaks this cycle. Meta-analyses have confirmed that consistent exercise training significantly reduces levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), a primary biomarker of systemic inflammation. This effect is particularly pronounced with aerobic training. The reduction in inflammation is a direct benefit that can alleviate fatigue and reduce the long-term cardiovascular risks associated with PCOS.

The effect of exercise on androgen levels is more complex. The primary mechanism through which exercise can lower androgens is indirect, by first lowering insulin. As insulin levels fall, the signal to the ovaries to overproduce testosterone is dampened.

Some studies suggest resistance training may be particularly helpful in improving the Free Androgen Index (FAI), which measures the amount of biologically active testosterone. It achieves this by increasing levels of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG), a protein that binds to testosterone and renders it inactive. The data on direct and consistent reduction of all androgen biomarkers through exercise alone is still developing, suggesting that while exercise is a powerful tool, it is one component of a comprehensive management strategy.

Academic

A molecular-level analysis reveals that exercise initiates a sophisticated biochemical dialogue that directly counteracts the pathophysiology of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. The contracting skeletal muscle functions as a paracrine and endocrine organ, releasing hundreds of bioactive peptides known as myokines. These molecules are central to understanding how mechanical work translates into systemic metabolic and anti-inflammatory effects.

The reversal of PCOS biomarker dysregulation through exercise is a story of restored cellular communication, orchestrated in large part by these powerful signaling proteins.

AMPK Activation and GLUT4 Translocation

At the heart of exercise-induced metabolic improvement is the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK is a master energy sensor within the cell. During exercise, the ratio of ATP to AMP decreases as energy is consumed, which activates AMPK. Once activated, AMPK initiates a cascade of events designed to restore energy homeostasis.

One of its most crucial functions is to stimulate the translocation of GLUT4 vesicles from the cell’s interior to the plasma membrane. This process, independent of the insulin-signaling pathway (which is impaired in PCOS), effectively opens new doorways for glucose to enter the muscle cell. This mechanism explains the immediate improvement in glucose tolerance following a single bout of exercise.

Chronic exercise training leads to an upregulation in the total protein content of both AMPK and GLUT4. This adaptation means the muscle is fundamentally rewired to be more efficient at glucose uptake, both during exercise and at rest. This increased capacity for glucose disposal in the body’s largest metabolic organ, skeletal muscle, directly reduces the secretory burden on the pancreas. Consequently, circulating insulin levels decrease, mitigating the downstream effects of hyperinsulinemia on ovarian androgen production and hepatic lipid synthesis.

The Myokine Response Anti-Inflammatory Signaling

The chronic low-grade inflammatory state in PCOS is characterized by elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6, often originating from hypertrophied adipocytes. Exercise provides a potent anti-inflammatory stimulus through the release of myokines.

| Myokine | Primary Function in PCOS Context | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | Acute anti-inflammatory signaling; enhanced insulin sensitivity. | When released from muscle, IL-6 stimulates the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-10) and inhibits TNF-α. It also increases glucose uptake and fat oxidation. |

| Irisin | Promotes browning of white adipose tissue; improves glucose homeostasis. | Increases energy expenditure by converting energy-storing white fat into metabolically active beige/brown fat. Enhances insulin sensitivity in the liver and muscle. |

| Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) | Central regulation of energy balance; neuronal health. | Acts on the hypothalamus to regulate appetite and energy expenditure. Also plays a role in fat oxidation. |

The role of IL-6 is particularly illustrative. While chronically elevated IL-6 from adipose tissue is pro-inflammatory, the transient, sharp peaks of IL-6 released from contracting muscle during exercise have a paradoxical, anti-inflammatory effect. This muscle-derived IL-6 promotes the release of other anti-inflammatory cytokines and directly inhibits the production of TNF-α. This explains the documented reduction in systemic inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein following exercise interventions.

The contracting muscle orchestrates a systemic anti-inflammatory effect by releasing myokines that actively suppress pro-inflammatory pathways.

What Are the Limitations of Exercise as a Monotherapy?

While the data strongly supports exercise as a foundational therapy, it is also important to recognize its limitations. Meta-analyses consistently show that while exercise alone, particularly vigorous exercise, significantly improves metabolic markers like HOMA-IR and cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2peak), its effect on body mass index (BMI) is modest.

The most substantial improvements in body composition and weight are typically seen when exercise is combined with dietary interventions. This is a matter of thermodynamics; creating a significant energy deficit for weight loss often requires addressing both energy expenditure (exercise) and energy intake (diet).

Furthermore, the normalization of reproductive and hormonal biomarkers can be less consistent. While reducing insulin resistance helps modulate ovarian function, direct and robust normalization of menstrual cycles or a consistent reduction in all androgenic biomarkers from exercise alone is not universally reported in the literature. This highlights that PCOS is a heterogeneous condition.

For many individuals, exercise is a powerful and essential component that restores foundational metabolic health, upon which other targeted therapies, whether nutritional or pharmacological, can be more effective. Exercise recalibrates the system, making it more responsive to other interventions.

References

- Patten, R. K. et al. “Exercise Interventions in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Frontiers in Physiology, vol. 11, 2020, p. 606.

- Taghian, F. et al. “The Effect of Exercise on Inflammatory Markers in PCOS Women ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials.” BioMed Research International, vol. 2023, 2023, Article ID 4575825.

- Woodward, A. et al. “Exercise Interventions in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Bohrium, 2020.

- Benham, J. L. et al. “Role of exercise training in polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Clinical Obesity, vol. 8, no. 4, 2018, pp. 275-284.

- Sadeghi, A. et al. “The Effect of Exercise on Inflammatory Markers in PCOS Women ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials.” PubMed, National Center for Biotechnology Information, 9 Feb. 2023.

Reflection

Your Body’s Potential

The data presented here provides a map, a detailed schematic of the biological pathways that connect your movement to your metabolic health. It translates the subjective feeling of wellness into the objective language of cellular biology. This knowledge is a tool, but you are the architect of your own health.

Consider the signals your body sends you. Think about how movement feels, what type of activity brings you a sense of strength, and how your energy levels respond not just today, but over weeks and months. This information, this deep listening to your own lived experience, is the most valuable dataset you will ever have.

The science provides the ‘how,’ but your personal experience provides the ‘when’ and ‘what.’ This journey is about building a partnership with your body, using movement as a way to reopen a dialogue and guide it back to its inherent potential for vitality and function.