Fundamentals

The feeling often begins subtly. A word that is suddenly out of reach, a misplaced set of keys, a momentary confusion in the middle of a familiar task. For many, the transition into perimenopause is marked by these cognitive shifts, a frustrating and sometimes frightening experience often described as “brain fog.” This experience is real, it is biologically grounded, and it represents a critical juncture in a woman’s long-term health.

Your brain, the most intricate and energy-demanding organ in your body, is profoundly sensitive to its biochemical environment. The symphony of hormones that has guided your reproductive life also plays a direct and continuous role in neural function, memory, and cognitive clarity.

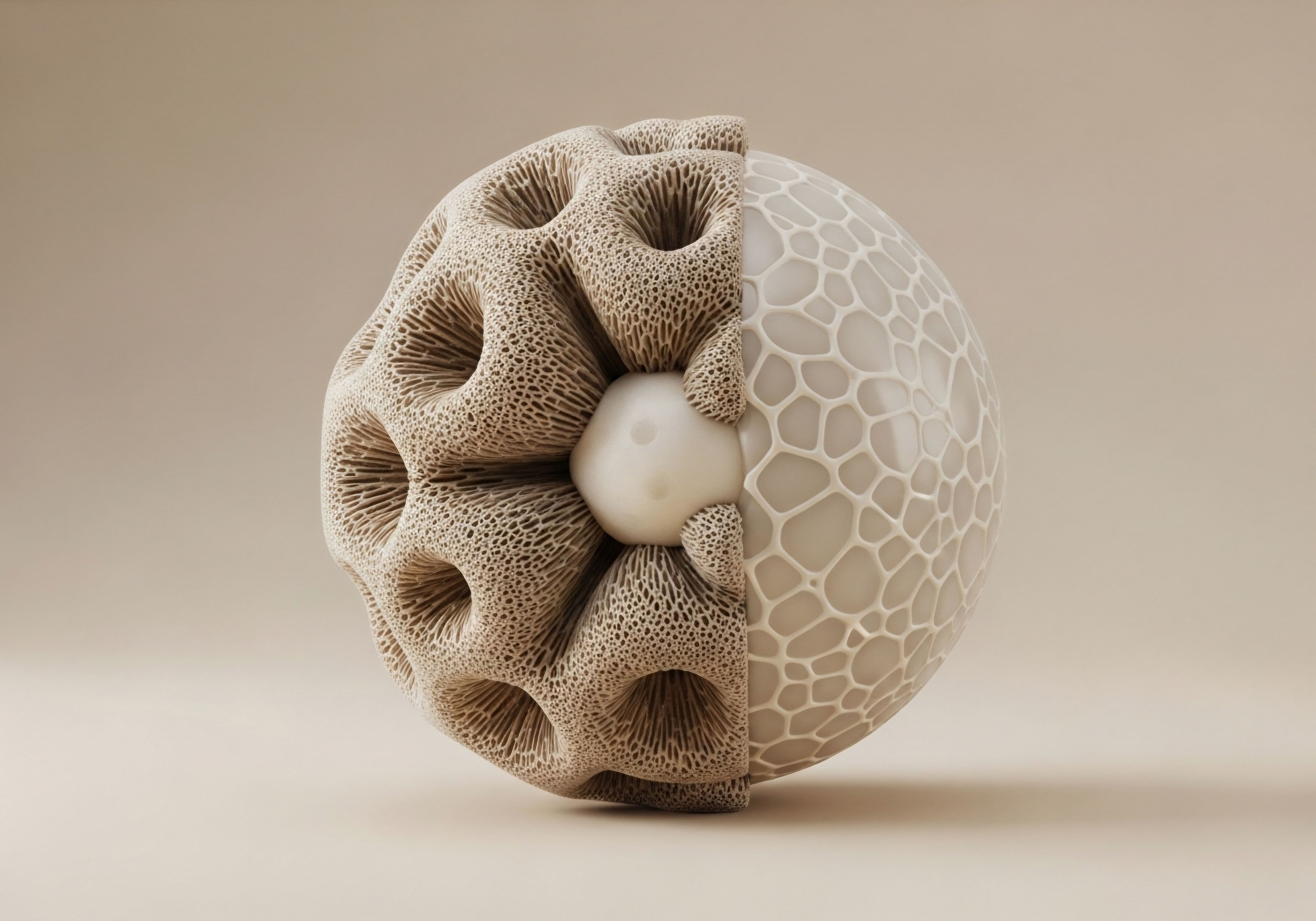

Understanding the connection between your hormones and your brain begins with appreciating the deep, systemic nature of your body’s internal communication network. At the center of this network is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, a sophisticated feedback loop that governs the production of your primary sex hormones.

The hypothalamus, a small region at the base of your brain, acts as the command center. It sends signals to the pituitary gland, which in turn relays instructions to the ovaries. The ovaries respond by producing estrogen and progesterone, the two principal hormones that orchestrate the menstrual cycle. These hormones then travel throughout the body, including back to the brain, influencing a vast array of physiological processes.

Perimenopause signifies a recalibration of the body’s primary hormonal communication system, with direct consequences for brain function and energy.

During the perimenopausal transition, this finely tuned system begins to fluctuate. The ovaries become less responsive to the signals from the pituitary gland, leading to erratic and eventually declining levels of estrogen and progesterone. This change is the root cause of the more commonly known symptoms like hot flashes and irregular cycles.

It is also the direct cause of the changes you may be experiencing in your cognitive function. Estrogen is a powerful neuroprotective agent. It supports the growth and survival of neurons, promotes the formation of new connections (synapses) between brain cells, and ensures robust blood flow to brain tissue.

When estrogen levels become unpredictable and begin to fall, the brain’s stable operating environment is disrupted. This disruption can manifest as difficulty with word retrieval, short-term memory lapses, and a general feeling of mental slowness.

What Is the Brain’s Relationship with Estrogen?

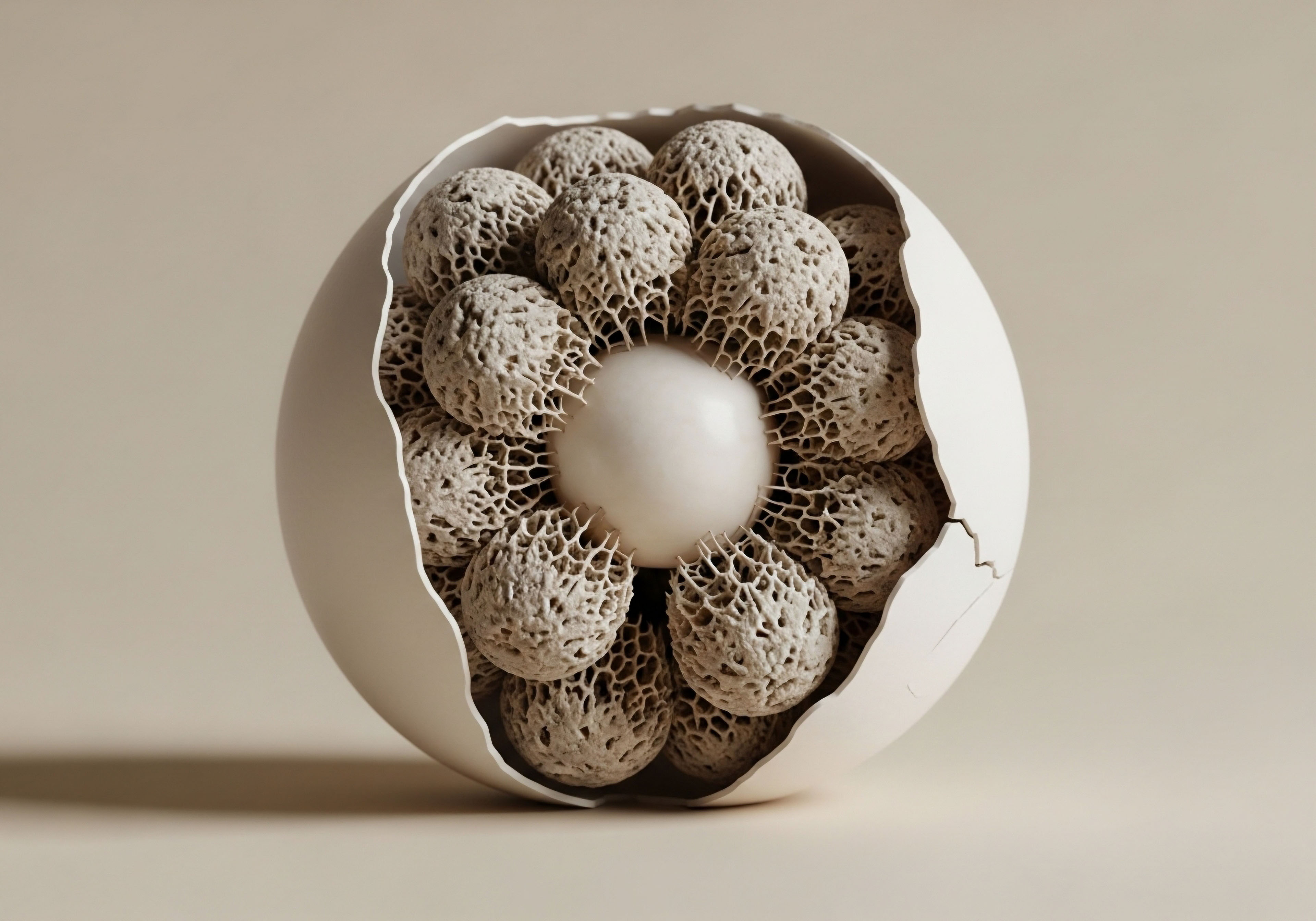

Estrogen’s role in the brain extends far beyond reproduction. It is a fundamental modulator of cognitive architecture. Think of it as a master regulator that ensures the brain’s infrastructure is well-maintained and its communication lines are clear. Brain regions critical for memory and higher-order thinking, such as the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex, are rich with estrogen receptors. When estrogen binds to these receptors, it triggers a cascade of beneficial cellular events.

- Neuron Growth and Repair Estrogen stimulates the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that acts like a fertilizer for brain cells, encouraging their growth, differentiation, and survival.

- Synaptic Plasticity It enhances the brain’s ability to form and reorganize synaptic connections, a process that is the cellular basis of learning and memory.

- Neurotransmitter Regulation Estrogen modulates the activity of key neurotransmitters, including serotonin, dopamine, and acetylcholine. These chemical messengers are vital for mood, focus, and memory recall. The decline in estrogen can disrupt their delicate balance, contributing to both cognitive symptoms and mood changes.

- Cerebral Blood Flow It helps maintain the health of blood vessels in the brain, ensuring a steady supply of oxygen and nutrients.

The perimenopausal decline in estrogen removes a key element of this protective and supportive framework. This is why addressing the hormonal changes of perimenopause is so deeply connected to preserving long-term cognitive vitality. The concept of a “critical window of opportunity” emerges from this understanding.

This theory suggests that the period of time around menopause is a unique and time-sensitive opportunity to intervene. By supporting the brain’s hormonal environment during this transition, it may be possible to mitigate the immediate cognitive symptoms and, more importantly, to reduce the risk of more significant cognitive decline in the decades that follow.

Intermediate

The validation of your cognitive symptoms opens the door to a more pressing question ∞ What can be done? The clinical conversation about perimenopausal intervention has evolved significantly, moving toward a more nuanced understanding of risk, benefit, and timing. The “critical window” hypothesis is central to this modern perspective.

This concept posits that initiating hormone therapy during perimenopause or in the early postmenopausal years (generally defined as within 10 years of the final menstrual period or before the age of 60) may confer unique neuroprotective benefits that are lost if therapy is started later in life.

During this window, the brain’s estrogen receptors are still plentiful and responsive. Providing estrogen during this time can help maintain the neural architecture and function that it has supported for decades. Starting therapy later, after a prolonged period of estrogen deprivation, may not be able to restore this function and in some cases, could have different effects.

Hormonal Optimization Protocols

When considering hormonal support, it is essential to understand the different therapeutic agents and how they work. The goal is to replicate the body’s natural hormonal milieu in a safe and effective way. Protocols are tailored to a woman’s individual health profile and whether she has a uterus.

For women experiencing perimenopausal symptoms, a typical approach involves a combination of estrogen and progesterone. Estrogen is the primary agent for addressing both vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes) and supporting cognitive and bone health. Progesterone is included to protect the uterine lining from the proliferative effects of estrogen.

For women who have had a hysterectomy, estrogen-only therapy is the standard. Low-dose testosterone may also be considered as an adjunct therapy for women experiencing persistent low libido, fatigue, and a diminished sense of well-being, even after their estrogen and progesterone levels are balanced.

Effective hormonal intervention during the critical perimenopausal window is about restoring biochemical balance to preserve neurological function.

The specific formulations used are a key part of the clinical decision-making process. Bioidentical hormones, which are structurally identical to the hormones produced by the human body, are often preferred. These include estradiol (the primary form of estrogen) and micronized progesterone. The route of administration is also a critical consideration.

Transdermal estradiol, delivered via a patch, gel, or spray, is often favored as it is absorbed directly into the bloodstream, bypassing the liver. This method has been associated with a lower risk of blood clots compared to oral estrogen. The table below outlines some common hormonal therapy components.

| Hormone Component | Primary Function in Therapy | Common Forms |

|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | Addresses vasomotor symptoms, supports bone density, and provides neuroprotective benefits. | Transdermal (patch, gel), Oral |

| Progesterone | Protects the endometrium from hyperplasia when estrogen is used in women with a uterus. | Micronized Progesterone (oral) |

| Testosterone | Addresses low libido, fatigue, and can improve mood and energy levels. | Subcutaneous injection, Cream, Pellet |

Interpreting the Evidence What Do the Studies Show?

The conversation around hormone therapy and cognition has been shaped by several large-scale studies with sometimes conflicting results. Understanding the context of these studies is essential. The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS), published in the early 2000s, reported an increased risk of dementia in women who initiated hormone therapy after the age of 65.

This study had a profound impact on clinical practice, leading to a sharp decline in the use of hormone therapy. The participants in WHIMS were, on average, many years past menopause, well outside the “critical window.” The formulations used, primarily oral conjugated equine estrogens and a synthetic progestin, are also different from the bioidentical hormones often used today.

In contrast, other studies focusing on younger women have shown more favorable outcomes. The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) investigated the effects of hormone therapy in recently menopausal women and found neutral effects on cognition, meaning it did not harm cognitive function. Observational studies have often suggested a protective effect.

A meta-analysis of multiple studies found that women who started estrogen therapy during perimenopause had a significantly lower risk of developing dementia. These findings support the “timing hypothesis,” suggesting that the apparent contradictions in the research can be largely explained by the age at which therapy is initiated. Early intervention appears to be the key factor for potential neuroprotection.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the potential for early perimenopausal intervention to prevent long-term cognitive decline requires a deep exploration of the molecular and metabolic mechanisms at play. The brain’s dependence on estrogen is not merely supportive; it is woven into the very fabric of its bioenergetic and signaling systems. The perimenopausal transition represents a profound shift in the brain’s metabolic paradigm, and it is at this level that the true opportunity for intervention lies.

The Neuroenergetic Role of Estrogen

The human brain accounts for approximately 2% of body weight but consumes about 20% of the body’s glucose, its primary fuel source. Estrogen is a master regulator of cerebral glucose metabolism. It facilitates the transport of glucose across the blood-brain barrier and into neurons and astrocytes.

Within the brain cells, estrogen upregulates the expression and activity of key glycolytic enzymes, ensuring efficient energy production. The decline of estrogen during perimenopause can lead to a state of cerebral glucose hypometabolism. This reduction in the brain’s ability to utilize its primary fuel source is a well-established hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease, and it can be detected decades before the onset of clinical symptoms.

Early hormonal intervention can be viewed as a strategy to preserve the brain’s energetic machinery, preventing this slow-motion energy crisis.

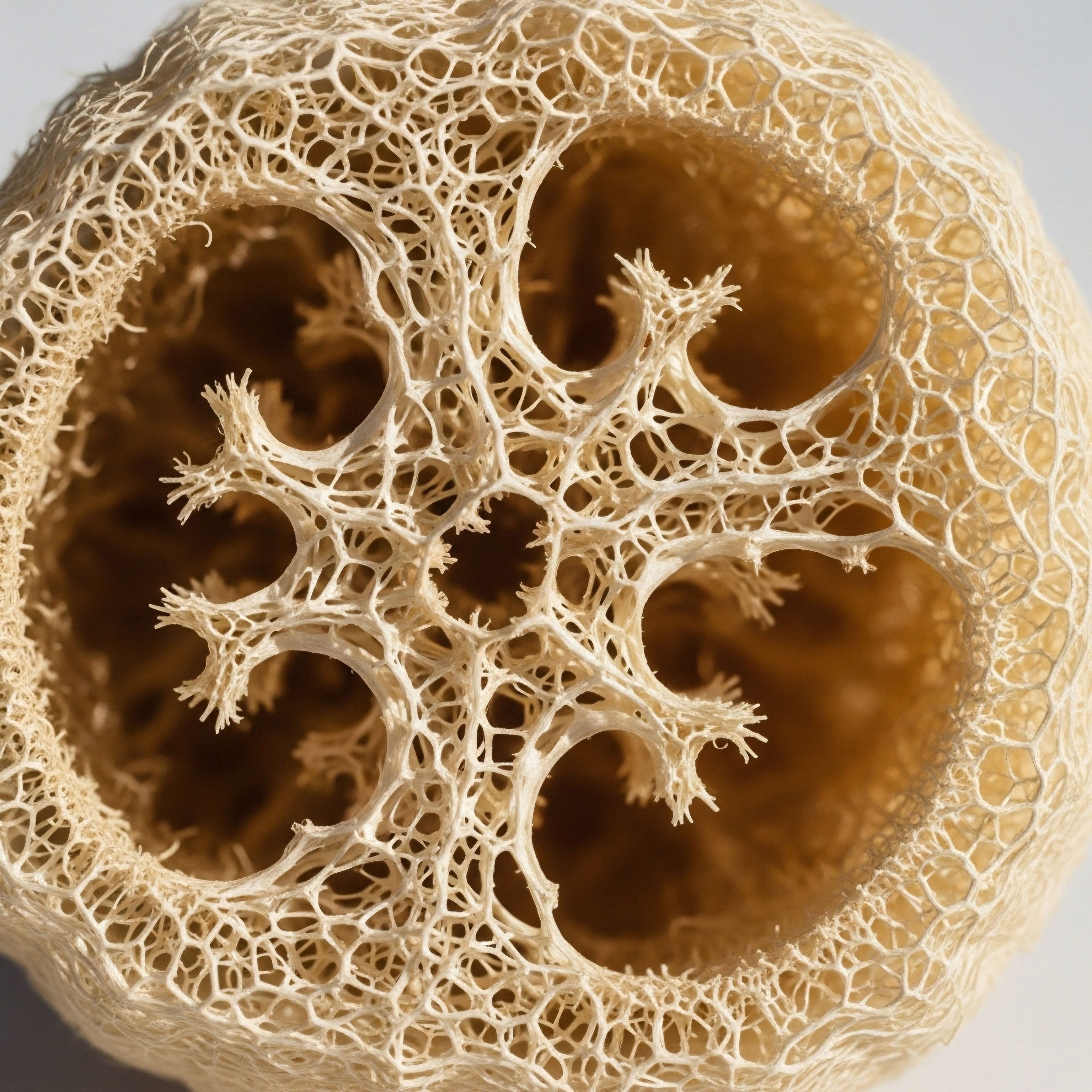

This energetic role is deeply intertwined with mitochondrial function. Mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cell, are responsible for generating ATP, the currency of cellular energy. Estrogen directly influences mitochondrial efficiency and health. It enhances the expression of mitochondrial genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation, the primary process of ATP production.

It also possesses antioxidant properties, helping to protect mitochondria from the damaging effects of oxidative stress, a natural byproduct of energy metabolism. The loss of estrogen can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction, reduced ATP output, and increased oxidative damage, all of which are implicated in the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases.

Preserving cognitive function through perimenopause is fundamentally about maintaining the brain’s bioenergetic stability and mitochondrial health.

How Does the Apoe4 Gene Influence Risk?

The conversation becomes even more specific when considering genetic predispositions. The Apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene provides the blueprint for a protein that transports cholesterol and other fats in the bloodstream. The APOE4 variant of this gene is the strongest known genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Women who carry the APOE4 allele appear to be particularly vulnerable to the neurological consequences of estrogen loss. Research suggests that the APOE4 protein is less efficient at lipid transport and neuronal repair compared to other variants. Estrogen appears to mitigate some of the negative effects of the APOE4 gene.

Therefore, the loss of estrogen in APOE4 carriers can create a “double hit” of increased genetic risk and loss of hormonal protection. For these individuals, the “critical window” may be even more significant, representing a crucial opportunity to counteract a potent genetic predisposition. The decision to initiate hormone therapy in an APOE4 carrier requires a detailed clinical discussion, weighing the potential neuroprotective benefits against any other health considerations.

The Interplay of Inflammation and the Hpg Axis

The HPG axis does not operate in a vacuum. It is in constant dialogue with the body’s immune system. Estrogen generally has anti-inflammatory properties within the central nervous system. It helps to suppress the activation of microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells.

When microglia become chronically activated, they release pro-inflammatory cytokines that can contribute to neuronal damage. The decline in estrogen during perimenopause can shift the brain’s immune environment towards a more pro-inflammatory state. This “neuroinflammation” is another key pathogenic mechanism in cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. By restoring estrogen levels, hormone therapy may help to quell this low-grade inflammation, preserving a healthier neural environment. The table below summarizes the mechanistic pillars of estrogen’s neuroprotective action.

| Mechanism | Effect of Estrogen | Consequence of Estrogen Decline |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose Metabolism | Enhances glucose transport and utilization in the brain. | Cerebral glucose hypometabolism and an energy deficit. |

| Mitochondrial Function | Promotes mitochondrial efficiency and reduces oxidative stress. | Mitochondrial dysfunction and increased oxidative damage. |

| Neuroinflammation | Suppresses microglial activation and pro-inflammatory cytokines. | A shift towards a chronic, low-grade neuroinflammatory state. |

| Synaptic Plasticity | Upregulates BDNF and promotes the formation of new synapses. | Reduced synaptic density and impaired learning and memory. |

Ultimately, the case for early perimenopausal intervention rests on a systems-biology perspective. The transition is a multi-faceted physiological event that impacts the brain’s energy supply, its immune status, its genetic vulnerabilities, and its capacity for self-repair.

Addressing the root cause of this instability, the decline in ovarian hormone production, offers a logical and mechanistically plausible strategy to promote long-term cognitive resilience. The evidence suggests that the timing of this intervention is paramount, making the perimenopausal years a period of unique therapeutic opportunity.

References

- Gleason, Christine E. et al. “Effects of hormone therapy on cognition and mood in newly postmenopausal women ∞ a randomized clinical trial.” PLoS medicine 12.6 (2015) ∞ e1001833.

- Najar, F. et al. “Reproductive period and dementia ∞ a 44-year longitudinal population study of Swedish women.” Alzheimer’s & Dementia 15.7 (2019) ∞ P114-P115.

- Rasgon, Natalie L. et al. “Apolipoprotein E genotype and verbal memory in healthy postmenopausal women.” Neuroscience 138.3 (2006) ∞ 737-746.

- Shumaker, Sally A. et al. “Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women ∞ the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study ∞ a randomized controlled trial.” Jama 289.20 (2003) ∞ 2651-2662.

- dei M, et al. “Cognitive Decline in Early and Premature Menopause – PMC.” PubMed Central, 31 Mar. 2023.

- “Hormone Therapy Can PREVENT Alzheimer’s Disease In Menopausal Women.” PR Newswire, 2 Nov. 2023.

- “Menopause and cognitive impairment ∞ A narrative review of current knowledge – PMC.” PubMed Central, 2021.

- “What Does the Evidence Show About Hormone Therapy and Cognitive Complaints?” The Menopause Society, 14 May 2025.

- “Hormone replacement therapy, menopausal age and lifestyle variables are associated with better cognitive performance at follow-up but not cognition over time in older-adult women irrespective of APOE4 carrier status and co-morbidities – Frontiers.” Frontiers, 16 Jan. 2025.

Reflection

You have now explored the intricate biological connections between your body’s hormonal systems and the clarity of your mind. This knowledge is a powerful tool. It transforms the conversation from one of passive symptom management to one of proactive, informed self-stewardship.

The data and the mechanisms provide a map, but you are the expert on the territory of your own body. The sensations you feel, the changes you observe, are valid and important data points in your personal health equation.

This information is the beginning of a dialogue. It is the foundation upon which you can build a collaborative partnership with a knowledgeable healthcare provider. The path forward is one of personalization, where your unique biology, health history, and future goals are considered in concert.

What does cognitive vitality look like for you in the decades to come? How can the science of hormonal health support that vision? The answers lie at the intersection of this clinical knowledge and your own deep understanding of your body’s needs. Your proactive engagement with your health during this pivotal transition is the most powerful intervention of all.

Glossary

perimenopause

brain fog

estrogen and progesterone

progesterone

estrogen

critical window

cognitive decline

hormone therapy

health initiative memory study

neuroprotection

cerebral glucose metabolism

apoe4