Fundamentals

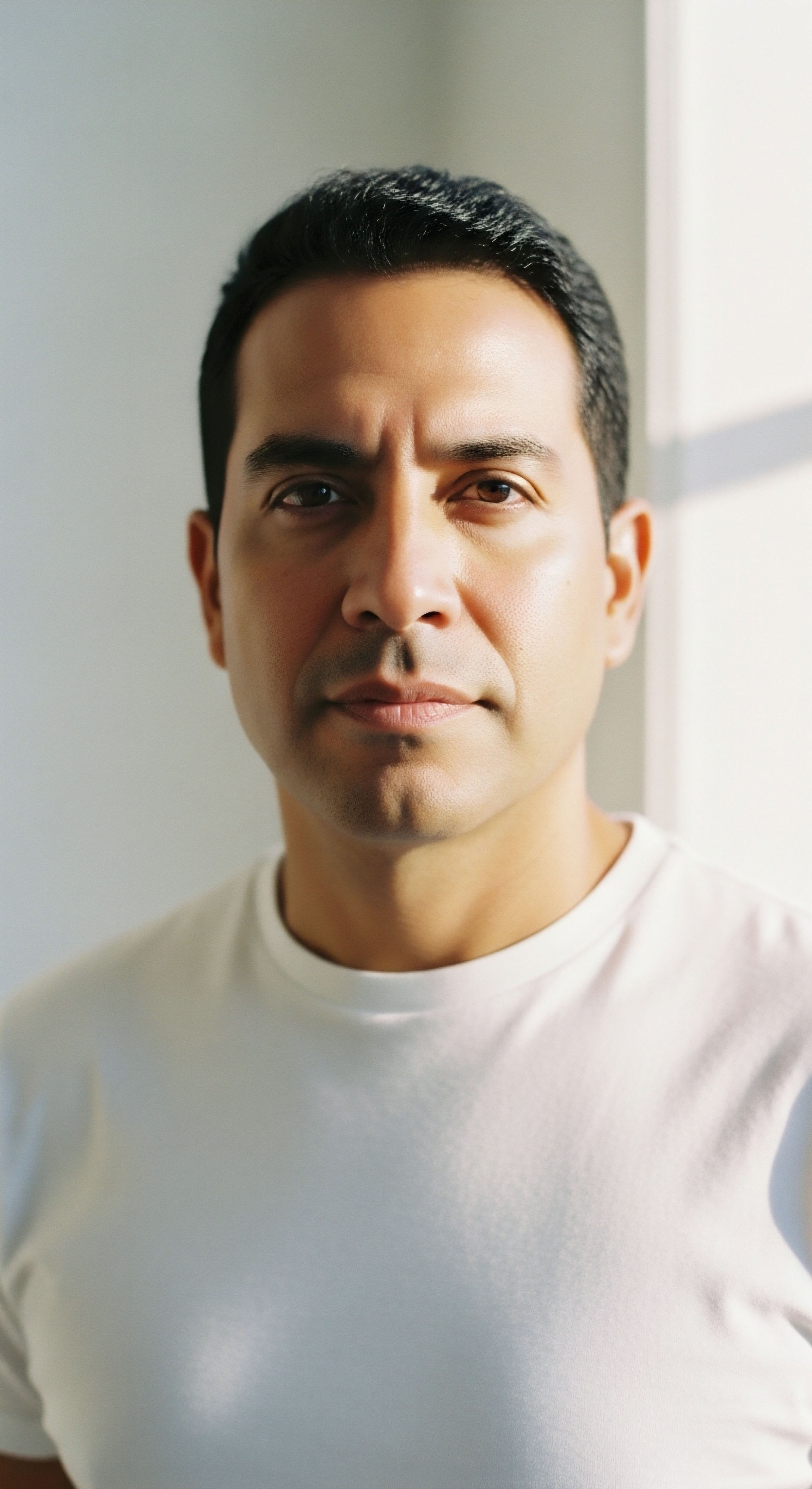

You have likely arrived here holding a deeply personal question, one that stems from a felt sense within your own body. Perhaps it is a persistent fatigue that sleep does not resolve, a shift in your mood or metabolism that feels foreign, or a general decline in vitality that you cannot pinpoint.

Your experience is the starting point. The question of whether dietary changes can, by themselves, fully restore the intricate communication network of your hormones is a profound one. The answer begins with understanding the nature of this internal system.

Your endocrine system operates as the body’s internal messaging service, a complex and beautifully orchestrated network of glands that produce and secrete hormones. These chemical messengers travel through your bloodstream, carrying instructions that regulate nearly every biological process, from your metabolic rate and stress response to your reproductive cycles and sleep patterns.

The quality and availability of the raw materials for these messages are determined, in large part, by your nutritional intake. Food provides the foundational building blocks for hormone production, the cofactors for their synthesis, and the energy required for their transport and reception.

To grasp the connection between diet and hormonal function, we must first look at the primary classes of nutrients. Macronutrients ∞ proteins, fats, and carbohydrates ∞ are the architectural components. Fats, particularly cholesterol, are the direct precursors for all steroid hormones, including testosterone, estrogen, and cortisol.

A diet severely lacking in healthy fats can deprive the body of the fundamental substrate it requires to build these vital molecules. Proteins are broken down into amino acids, which are then used to construct peptide hormones like insulin and growth hormone. Carbohydrates, and your body’s response to them, govern the master metabolic hormone, insulin.

The stability of your blood sugar is a primary determinant of overall hormonal equilibrium. When blood sugar swings dramatically due to the consumption of highly processed carbohydrates and sugars, the resulting surges in insulin can create a cascade of disruptions across other hormonal systems. This is a key reason why a foundational dietary strategy for hormonal wellness centers on blood glucose stabilization. It creates a calm and predictable metabolic environment, allowing other hormonal conversations to proceed without interruption.

Your body’s hormonal communication network is built directly from the nutrients you consume, making diet a primary lever for influencing its function.

Beyond the macronutrients, micronutrients ∞ vitamins and minerals ∞ function as the skilled technicians of the endocrine system. They act as essential cofactors in the enzymatic reactions that convert precursor molecules into active hormones. Zinc, for instance, is integral to the production of testosterone.

Selenium is required for the conversion of inactive thyroid hormone (T4) to its active form (T3). Vitamin D, which functions more like a hormone itself, plays a regulatory role in hundreds of bodily processes, including insulin sensitivity and sex hormone production.

Without a sufficient supply of these micronutrients, the assembly line of hormone synthesis can slow down or become inefficient, even if all the primary building blocks are present. A diet rich in a wide variety of whole foods, full of color and diversity, is the most reliable way to ensure a complete profile of these necessary cofactors.

This is the first principle of using nutrition to support your internal biochemistry ∞ you must provide the system with all of its required parts, in the proper amounts, to facilitate its intended design.

The relationship between your diet and your hormones is therefore an intimate one. Nutritional choices directly influence the production, signaling, and metabolism of these powerful chemical messengers. A diet centered on whole, unprocessed foods provides the necessary building blocks and enzymatic support for healthy endocrine function.

Conversely, a diet high in processed ingredients, refined sugars, and unhealthy fats can introduce systemic inflammation and metabolic chaos, disrupting this delicate balance. Understanding these foundational principles is the first step in a personal journey toward biological reclamation.

It validates your lived experience by connecting the symptoms you feel to the underlying biological mechanisms that can be directly influenced by the choices you make every day. The question then evolves from if diet has an effect, to how deep that effect goes and what its limitations are when faced with more complex physiological challenges.

Intermediate

Moving beyond foundational principles, we can examine the specific mechanisms through which diet interacts with key hormonal axes. The conversation is not just about providing raw materials; it is about how nutritional patterns modulate the sensitivity of receptors and the feedback loops that govern hormonal homeostasis.

A primary modulator of the entire endocrine system is the hormone insulin. Its role is to manage blood glucose, but its influence extends far beyond that, directly impacting the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, which controls reproductive function and sex hormone production in both men and women.

Chronic elevation of insulin, a state known as insulin resistance, is a significant disruptor. In men, high insulin levels are associated with lower levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), which means more free testosterone is available initially, but it also promotes the activity of the aromatase enzyme, converting testosterone to estrogen.

Over time, this can lead to symptoms of low testosterone and high estrogen. In women, insulin resistance is a hallmark of conditions like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), where high insulin levels stimulate the ovaries to produce excess androgens, disrupting ovulation and menstrual cycles.

Dietary modifications that improve insulin sensitivity ∞ such as reducing the intake of refined carbohydrates, increasing fiber and protein, and ensuring adequate healthy fats ∞ can therefore have a direct and powerful effect on sex hormone balance. This is a clear example of how a targeted dietary strategy can address a root cause of hormonal dysregulation.

How Does Insulin Dysregulation Impede Testosterone Synthesis?

The intricate dance between insulin and testosterone is a central aspect of male metabolic and hormonal health. When the body’s cells become less responsive to insulin, the pancreas compensates by producing more of it, leading to hyperinsulinemia. This state directly impacts Leydig cells in the testes, which are responsible for producing testosterone.

Research indicates that persistent high levels of insulin can impair the signaling pathways within these cells, reducing their capacity for testosterone synthesis. Furthermore, the obesity that often accompanies insulin resistance creates another layer of complexity. Adipose (fat) tissue is not inert; it is a metabolically active organ that produces inflammatory cytokines and the enzyme aromatase.

As detailed previously, aromatase converts testosterone into estradiol, the primary form of estrogen. Consequently, a man with significant insulin resistance and associated obesity finds himself in a challenging biochemical loop ∞ impaired testosterone production combined with increased conversion of the remaining testosterone to estrogen.

Dietary interventions aimed at restoring insulin sensitivity, such as a low-glycemic load diet or a Mediterranean-style eating pattern, can help break this cycle by reducing the insulin burden and promoting fat loss, thereby decreasing aromatase activity.

Stabilizing blood sugar through diet is a powerful intervention for improving sex hormone balance by directly addressing the disruptive effects of insulin resistance.

Dietary Support for Male and Female Hormonal Protocols

When dietary modifications alone are insufficient to restore optimal function due to the degree of physiological compromise, clinical protocols like hormone replacement therapy (HRT) become a necessary and effective intervention. Nutrition, however, continues to play a vital supportive role.

For a man on a Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) protocol, which may include Testosterone Cypionate, Gonadorelin, and an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole, diet is foundational for success. A protein-rich diet ensures the building blocks for muscle protein synthesis are available, allowing the body to fully utilize the anabolic signals from the restored testosterone levels.

Micronutrients like zinc and magnesium remain important for endogenous hormonal processes, while a diet that manages inflammation can improve overall well-being and cellular health. Similarly, for a woman on a protocol involving low-dose Testosterone Cypionate and Progesterone for perimenopausal symptoms, nutrition is a key partner.

A diet rich in phytoestrogens from sources like flax seeds and soy can provide a gentle, supportive effect on estrogen pathways. Calcium and Vitamin D become particularly important for bone health as estrogen levels fluctuate. Managing blood sugar is also paramount, as the hormonal shifts of perimenopause can themselves exacerbate insulin resistance. In both male and female protocols, diet acts as a synergistic force, creating a biological environment where the therapeutic interventions can be most effective.

The following table outlines how different dietary patterns can influence insulin sensitivity, a key factor in hormonal health.

| Dietary Pattern | Primary Components | Mechanism of Action on Insulin Sensitivity | Impact on Hormonal Balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western Diet |

High in processed foods, refined sugars, saturated and trans fats. |

Promotes chronic inflammation and high glycemic load, leading to hyperinsulinemia and eventual insulin resistance. |

Disrupts HPG axis; associated with low testosterone in men and androgen excess in women. |

| Mediterranean Diet |

Rich in whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and olive oil; moderate fish and poultry. |

High in fiber and monounsaturated fats; low glycemic load. Reduces inflammation and improves cell membrane fluidity, enhancing insulin receptor function. |

Supports healthy testosterone levels and SHBG; improves menstrual regularity in women. |

| Low-Carbohydrate Diet |

Restricts carbohydrates while emphasizing protein and fats. |

Lowers circulating glucose and insulin levels directly, forcing the body to improve its sensitivity to smaller amounts of insulin. |

Can be effective in reversing insulin resistance-related hormonal issues like PCOS. Long-term effects require monitoring. |

| Plant-Based Diet |

Emphasizes foods derived from plants; excludes or minimizes animal products. |

Typically very high in fiber and low in saturated fat, which can improve insulin sensitivity and gut microbiome health. |

Effects can vary; some studies show lower testosterone levels, potentially due to low fat intake or high phytoestrogen content. |

The Role of Nutrition in Peptide Therapies

Peptide therapies, such as those using Growth Hormone Releasing Hormones (GHRHs) like Sermorelin or Growth Hormone Secretagogues like Ipamorelin, represent another tier of intervention for optimizing health and vitality. These peptides work by stimulating the pituitary gland to produce and release more of the body’s own growth hormone (GH).

This process is metabolically demanding and is heavily reliant on nutritional status. For the pituitary to synthesize GH, it requires a rich supply of amino acids, the building blocks of all proteins. A diet that is adequate, or even abundant, in high-quality protein is therefore a prerequisite for getting the maximum benefit from these protocols.

Furthermore, the downstream effects of increased GH, such as muscle repair and cellular regeneration, also require sufficient protein intake. These therapies do not create results from nothing; they amplify the body’s own regenerative systems. Nutrition provides the fuel and raw materials for that amplification. A comprehensive approach will always pair a sophisticated clinical protocol with a foundational, supportive, and nutrient-dense dietary strategy. This ensures the body is fully equipped to respond to the therapeutic signals being provided.

Academic

A sophisticated examination of the limits of dietary intervention on hormonal balance requires moving beyond direct nutrient-hormone interactions and into a systems-biology perspective. The dominant path for this deep exploration is the Gut-Hormone Axis.

The gastrointestinal tract is now understood as the body’s largest endocrine organ, a complex ecosystem where diet, microbial life, and host physiology converge to regulate systemic hormonal signaling. The capacity of dietary modifications to restore hormonal balance is fundamentally constrained by the health and integrity of this axis.

Three interconnected areas are of primary importance ∞ the metabolic activity of the gut microbiome, the integrity of the intestinal barrier, and the production of gut-derived signaling molecules like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

The Microbiome as an Endocrine Regulator

The trillions of microbes residing in the human gut possess a vast collective genome with an enzymatic capacity that far exceeds that of the human host. This microbial machinery actively participates in endocrine regulation. A key example is the “estrobolome,” a specialized collection of gut bacteria that possess genes capable of metabolizing estrogens.

These microbes produce β-glucuronidase enzymes, which can deconjugate estrogens that have been processed by the liver and sent to the gut for excretion. This deconjugation reactivates the estrogens, allowing them to be reabsorbed into circulation. A dysbiotic, or imbalanced, gut microbiome can lead to either an under-activity or over-activity of the estrobolome.

High β-glucuronidase activity, often driven by a diet low in fiber and high in processed fats, can increase the pool of circulating estrogens, potentially contributing to conditions of estrogen dominance in both women and men. Conversely, certain beneficial bacteria help to maintain a balanced level of this enzyme. Therefore, dietary strategies that cultivate a healthy microbiome ∞ rich in fermentable fibers (prebiotics) from sources like onions, garlic, and asparagus ∞ can directly modulate estrogen metabolism and circulation.

The microbiome’s influence extends to androgens as well. Certain species of gut bacteria can produce SCFAs, which have been shown to influence testosterone levels. For example, butyrate, a primary SCFA, can signal through various pathways to support Leydig cell function in the testes.

A diet lacking in the dietary fiber necessary for SCFA production can lead to a gut environment that is less supportive of optimal androgen synthesis. This microbial influence represents a critical, and often overlooked, mechanism by which diet dictates hormonal status. When the microbial ecosystem is severely compromised, simply providing the nutritional precursors for hormones may be insufficient, as the metabolic “factory” in the gut is not functioning correctly.

The gut microbiome functions as a critical endocrine organ, directly metabolizing hormones and producing signaling molecules that regulate systemic hormonal balance.

Intestinal Barrier Integrity and Systemic Inflammation

The lining of the intestine forms a critical barrier between the external world (the contents of the gut) and the internal environment of the body. When this barrier is compromised, a condition often referred to as increased intestinal permeability or “leaky gut,” it can trigger a cascade of hormonal disruptions.

Dietary components, particularly gluten in susceptible individuals, and emulsifiers found in processed foods, can degrade the tight junctions that hold intestinal cells together. This allows bacterial components, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), to translocate from the gut lumen into the bloodstream. LPS is a potent endotoxin that elicits a strong inflammatory response from the host’s immune system.

This low-grade, chronic systemic inflammation has profound effects on the endocrine system. It can blunt the sensitivity of hormone receptors, making tissues less responsive to hormones like insulin and thyroid hormone. Inflammation also directly stimulates the adrenal glands to produce cortisol.

Chronically elevated cortisol can suppress the HPG axis, leading to reduced production of testosterone and estrogen. This creates a vicious cycle where poor diet compromises gut integrity, which drives inflammation, which in turn disrupts hormonal balance system-wide.

While a whole-foods, anti-inflammatory diet is the correct therapeutic approach, in cases of severe, long-standing gut dysbiosis and permeability, dietary changes alone may be slow to heal the barrier and quell the inflammatory cascade. In such scenarios, the hormonal systems may remain suppressed or dysregulated until gut health is more fully restored, sometimes requiring targeted interventions beyond diet.

What Is the Role of Dietary Fiber in Hormone Modulation?

Dietary fiber is not an inert bulking agent. It is a primary fuel source for the gut microbiome, and its fermentation leads to the production of SCFAs like butyrate, propionate, and acetate. These molecules are not merely metabolic byproducts; they are potent signaling molecules with systemic endocrine effects.

Butyrate, for example, is the primary energy source for colonocytes, the cells lining the colon, thereby helping to maintain intestinal barrier integrity. SCFAs also play a direct role in hormone regulation. They stimulate the release of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) from L-cells in the gut.

GLP-1 is an incretin hormone that enhances insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner, improves insulin sensitivity, slows gastric emptying, and promotes satiety. Through its effects on insulin sensitivity and weight management, the GLP-1 system indirectly supports the entire endocrine network. Some research also suggests GLP-1 has direct effects on the HPG axis.

A diet rich in diverse fibers is the only way to ensure robust production of these beneficial SCFAs. The following table details specific food components and their inflammatory or anti-inflammatory potential, which is a key mechanism in the Gut-Hormone axis.

| Component | Primary Dietary Sources | Pro-inflammatory/Anti-inflammatory Mechanism | Consequence for Hormonal Health |

|---|---|---|---|

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids |

Fatty fish (salmon, mackerel), flaxseeds, walnuts. |

Serve as precursors to anti-inflammatory eicosanoids (prostaglandins, resolvins). They compete with pro-inflammatory omega-6 fatty acids. |

Reduces systemic inflammation, improving insulin sensitivity and protecting endocrine glands from oxidative stress. |

| Refined Sugars |

Soda, candy, baked goods, many processed foods. |

Promote the formation of Advanced Glycation End-products (AGEs), which are highly inflammatory. Drive hyperinsulinemia. |

Contributes to insulin resistance, which directly disrupts sex hormone balance and increases cortisol. |

| Polyphenols |

Berries, dark chocolate, green tea, colorful vegetables. |

Act as antioxidants and directly inhibit pro-inflammatory pathways like NF-κB. They also promote a healthy gut microbiome. |

Protects endocrine tissues from damage and supports a gut environment conducive to hormonal balance. |

| Trans Fats |

Partially hydrogenated oils found in some margarines, fried foods, and packaged snacks. |

Induce a powerful systemic inflammatory response and are associated with endothelial dysfunction and increased visceral fat. |

Strongly associated with insulin resistance and disruption of nearly all hormonal axes. |

In conclusion, from an academic, systems-biology perspective, the question of whether diet alone can restore hormonal balance is a question of the integrity of the Gut-Hormone axis. In an individual with a resilient and diverse microbiome, a strong intestinal barrier, and efficient SCFA production, dietary modifications are an exceptionally powerful tool, capable of producing profound shifts in hormonal health.

However, in an individual with severe dysbiosis, significant intestinal permeability, and entrenched systemic inflammation, the system’s ability to respond to dietary inputs is compromised. The communication lines are down. In these cases, while diet is a non-negotiable foundation for any therapeutic protocol, it may not be sufficient on its own.

The restoration of hormonal balance may require a multi-pronged approach that includes targeted interventions to heal the gut, reduce inflammation, and, when necessary, provide direct hormonal support through clinical protocols like HRT or peptide therapy. The diet sets the stage, but the complexity of the individual’s physiology dictates how many other actors are needed for the play.

References

- Whittaker, J. & Wu, K. (2021). Low-fat diets and testosterone in men ∞ Systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 210, 105878.

- Gaskins, A. J. Chiu, Y. H. Williams, P. L. Ford, J. B. Toth, T. L. Hauser, R. & Chavarro, J. E. (2015). Association between serum folate and vitamin B-12 and outcomes of assisted reproductive technologies. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 102(4), 943 ∞ 950.

- Salas-Huetos, A. Ros, E. & Salas-Salvadó, J. (2017). Dietary patterns, foods and nutrients in male fertility parameters and fecundability ∞ a systematic review of observational studies. Human reproduction update, 23(4), 371-389.

- Pellatt, L. Hanna, L. & Mason, H. D. (2007). The role of insulin-like growth factor I in the regulation of human ovarian function. Journal of Endocrinology, 192(2), 233-245.

- Baker, J. M. Al-Nakkash, L. & Herbst-Kralovetz, M. M. (2017). Estrogen-gut microbiome axis ∞ Physiological and clinical implications. Maturitas, 103, 45 ∞ 53.

- Baskind, N. E. & Balasubramanian, R. (2020). The role of diet and nutrition in male-factor infertility. Current urology reports, 21(11), 1-8.

- Cutini, M. D’Amico, F. & Giannini, S. (2022). Nutrition and male fertility ∞ an evidence-based review. Journal of clinical medicine, 11(19), 5783.

- Skoracka, K. Ratajczak, A. E. Rychter, A. M. Dobrowolska, A. & Krela-Kaźmierczak, I. (2021). Female fertility and the nutritional approach ∞ the most important aspects. Advances in Nutrition, 12(6), 2372-2386.

Reflection

Your Personal Biological Narrative

The information presented here offers a map, a detailed guide to the intricate biological landscape within you. It connects the foods you consume to the delicate chemical conversations that dictate how you feel and function. Your body is constantly communicating its needs and its state of balance through the signals you experience daily ∞ your energy, your mood, your sleep, your resilience.

The journey toward optimal wellness is one of learning to listen to and interpret this personal biological narrative. The knowledge of how dietary choices influence insulin, support testosterone production, or modulate estrogen metabolism is empowering. It transforms the act of eating from a daily necessity into a conscious act of biological stewardship.

Consider the patterns in your own life. Think about the times you have felt your best. What were the inputs then? This process of introspection, of connecting your choices to your state of being, is the first and most meaningful step.

The science provides the ‘why,’ but your personal experience provides the ‘what.’ A personalized path forward is built at the intersection of these two forms of knowledge, often with the guidance of a clinical expert who can help you read your own unique map and navigate the terrain ahead.