Fundamentals

You feel it in your bones, a subtle yet persistent shift in the way your body operates. The energy that once came so easily now feels like a resource to be carefully managed. Your sleep may be less restorative, your moods more volatile, and your body composition seems to be changing in ways that feel foreign and frustrating.

This lived experience is your body’s primary form of communication, a rich dataset that speaks to the intricate internal symphony of your hormonal health. When we discuss restoring balance, we are truly talking about understanding and responding to these signals.

The question of whether dietary modifications can, by themselves, bring your estrogen metabolism back into a state of equilibrium is a profound one. It speaks to a desire to reclaim agency over your own biology, to use the most fundamental inputs ∞ the foods you consume ∞ to guide your system back to its optimal state.

To begin this exploration, we must first appreciate the journey estrogen takes through the body. This is a story of creation, action, and eventual deactivation and elimination. Estrogen is produced primarily in the ovaries in women and, to a lesser extent, in the adrenal glands and fat tissue for both sexes.

In men, a significant portion of estrogen is synthesized from testosterone. Once produced, it travels through the bloodstream, acting as a powerful messenger that influences everything from bone density and cardiovascular health to cognitive function and mood. After it has delivered its messages by binding to specific receptors on cells, the body must prepare it for removal. This detoxification process is a sophisticated, multi-step operation, primarily managed by two key organ systems ∞ the liver and the gut.

Think of your liver as the primary metabolic processing plant. It receives used estrogen from the bloodstream and, through a two-phase process, chemically alters it to be less potent and water-soluble, preparing it for excretion. This is an elegant and energy-dependent biochemical assembly line.

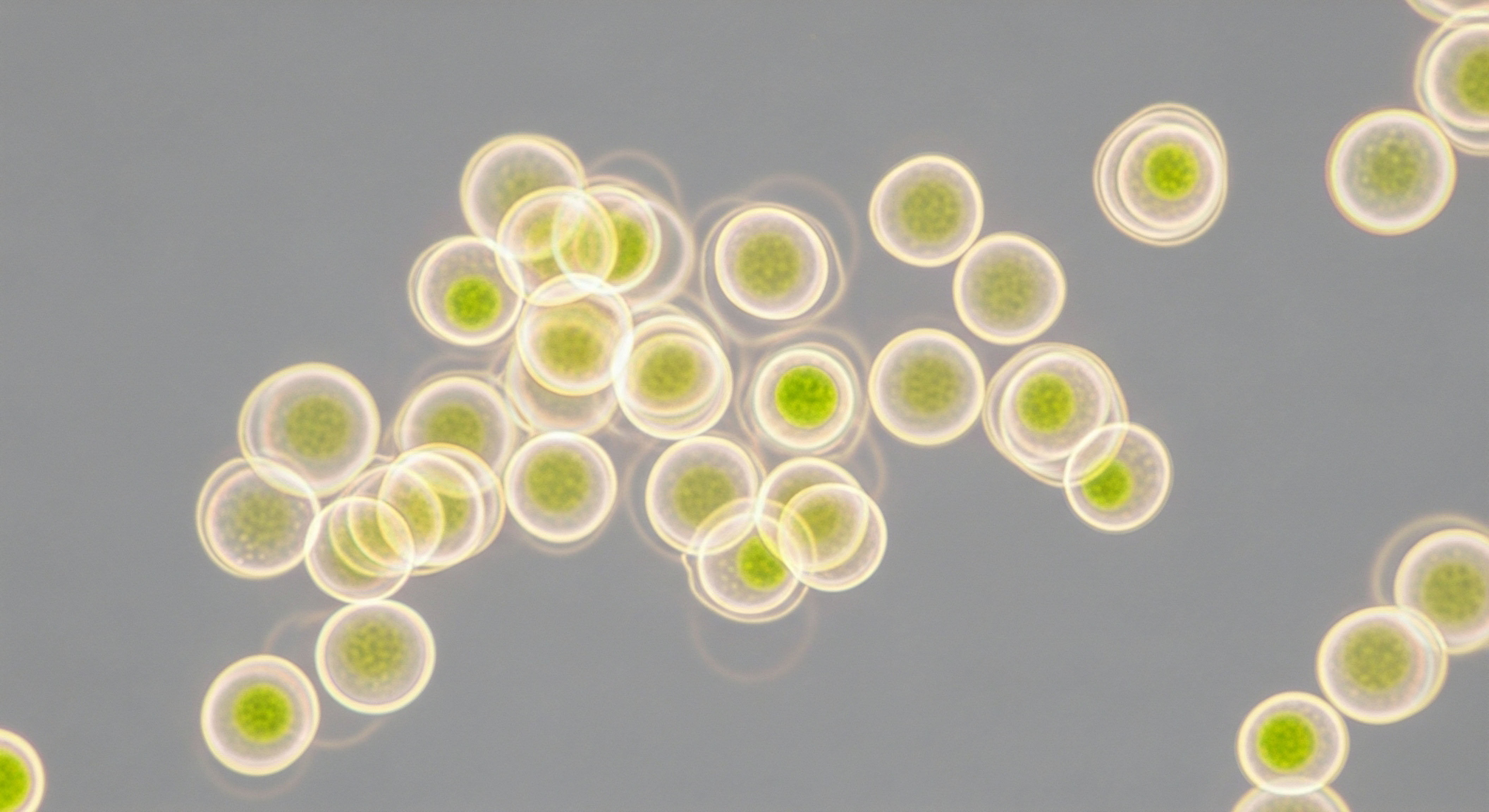

Following the liver’s work, the processed estrogen is sent to the gut. Here, it is intended to be escorted out of the body through stool. This is where the narrative becomes even more fascinating. Your gut is home to a vast and complex ecosystem of microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiome. Within this ecosystem resides a specialized collection of bacteria with a particular talent for metabolizing estrogens. Scientists have named this microbial community the ‘estrobolome’.

The intricate dance between your liver and gut microbiome orchestrates the final chapter of your body’s estrogen story, determining its healthy elimination or problematic recirculation.

The health and diversity of this estrobolome are absolutely central to hormonal balance. These gut bacteria produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. When this enzyme’s activity is high, it can effectively “unpackage” the estrogen that the liver so carefully prepared for disposal.

This deconjugated, or “free,” estrogen is now active again and can be reabsorbed back into the bloodstream, adding to the body’s total estrogen load. A healthy, balanced estrobolome keeps beta-glucuronidase activity in check, ensuring that estrogen is efficiently eliminated.

An imbalanced or dysbiotic gut, conversely, can lead to excessive estrogen recirculation, contributing to the very symptoms of hormonal imbalance that you may be experiencing. Understanding this connection is the first, most empowering step. It reframes the question from a simple list of “good” and “bad” foods to a more sophisticated inquiry ∞ How can we use diet to intentionally cultivate a biological environment in the liver and the gut that supports perfect estrogen metabolism?

The Language of Your Hormones

Your body’s symptoms are its voice. The fatigue, the brain fog, the shifts in your menstrual cycle, or the unwelcome changes in your physique are not random failings. They are signals, rich with information about your internal environment. From a clinical perspective, these experiences are the starting point of our investigation.

They guide us toward understanding the underlying mechanics of your physiology. Hormonal equilibrium is a state where the production, signaling, and detoxification of hormones like estrogen happen in a seamless, coordinated rhythm. An imbalance occurs when any part of this lifecycle is disrupted.

The feeling of being “off” is often the subjective experience of a systemic biological disruption. The foods you choose to eat every day represent the most consistent and powerful tool you have to influence this system. Diet provides the raw materials and the operational instructions that your liver and gut microbiome require to perform their functions correctly.

Therefore, the journey to restoring equilibrium begins with learning to speak your body’s language and providing it with the precise nutritional information it needs to recalibrate.

Intermediate

Acknowledging the foundational roles of the liver and gut in estrogen metabolism allows us to move into a more granular, actionable phase of our discussion. The path to restoring equilibrium through diet is paved with specific, targeted nutritional strategies that directly support these systems.

This involves supplying the precise biochemical cofactors for hepatic detoxification and cultivating a gut microbiome that ensures the final, successful excretion of estrogen. This is a proactive approach, using food as a daily modulator of your endocrine function. We will now examine the specific dietary components that empower these biological processes, moving from broad concepts to a detailed clinical application of nutrition.

How Do You Nourish the Estrobolome?

The estrobolome, that specialized community of gut microbes, functions as a critical control valve for estrogen levels. Its health dictates whether estrogen is safely excreted or sent back into circulation. A diverse and robust microbiome maintains low levels of the enzyme beta-glucuronidase, which is favorable for hormonal balance. Cultivating this internal garden is a primary objective of any dietary protocol for estrogen equilibrium. The key lies in providing the right kinds of fuel for beneficial bacteria to flourish.

Dietary fiber is the undisputed hero in this context. Humans lack the enzymes to digest fiber, so it passes through the small intestine to the large intestine, where it becomes the primary food source for our resident microbes.

A high-fiber diet has a dual benefit ∞ it feeds beneficial bacteria, promoting a healthy microbial composition, and it physically binds to estrogen in the gut, ensuring its passage out of the body. Aiming for a daily intake of 30-40 grams of diverse fiber is a clinical goal.

This diversity is important; different types of fiber feed different families of bacteria, leading to a more resilient and functional microbial ecosystem. Soluble fiber, found in oats, barley, apples, and beans, forms a gel-like substance that slows digestion and is readily fermented by gut bacteria. Insoluble fiber, found in nuts, seeds, and the skins of vegetables, adds bulk to the stool, promoting regular bowel movements, which is a critical mechanism for estrogen removal.

Consuming a wide variety of plant-based foods is the most effective strategy for cultivating a diverse microbiome, which is essential for healthy estrogen regulation.

Beyond fiber, probiotic and prebiotic foods directly contribute to the health of the estrobolome. Probiotic foods contain live, beneficial bacteria, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species, which have been shown to support gut health and modulate immune function. Fermented foods like kimchi, sauerkraut, kefir, and unsweetened yogurt are excellent sources.

Prebiotic foods contain specific types of fiber, like inulin and fructooligosaccharides, that are particularly effective at stimulating the growth of beneficial bacteria. Onions, garlic, leeks, asparagus, and Jerusalem artichokes are rich in these compounds. Incorporating these foods regularly provides both the “seeds” (probiotics) and the “fertilizer” (prebiotics) for a healthy gut environment.

| Food Group | Primary Contribution | Examples | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soluble Fiber Sources | Feeds beneficial bacteria, forms gel to bind estrogen | Oats, apples, citrus fruits, carrots, barley, psyllium, beans | Fermented by gut microbes into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) which nourish colon cells and support a healthy gut lining. |

| Insoluble Fiber Sources | Promotes bowel regularity for estrogen excretion | Whole grains, nuts, seeds, cauliflower, green beans, potatoes | Adds bulk to stool, reducing transit time and preventing the reabsorption of deconjugated estrogen. |

| Probiotic Foods | Introduces beneficial bacteria | Kimchi, sauerkraut, kefir, miso, tempeh, unsweetened yogurt | Helps to populate the gut with microbes that support a healthy estrobolome and compete with less desirable bacteria. |

| Prebiotic Foods | Provides targeted fuel for beneficial bacteria | Garlic, onions, leeks, asparagus, dandelion greens, bananas | Stimulates the growth of healthy bacteria like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, which help maintain gut barrier integrity. |

Supporting Hepatic Detoxification Pathways

While the gut handles the final stage of estrogen elimination, the liver performs the critical preparatory work. This process, known as biotransformation, occurs in two phases. Phase I, driven by a family of enzymes called Cytochrome P450, involves hydroxylation, a chemical reaction that begins to transform the estrogen molecule.

This phase can produce different types of estrogen metabolites. The 2-hydroxyestrone (2-OHE1) pathway is considered the most protective, while the 4-hydroxyestrone (4-OHE1) and 16-alpha-hydroxyestrone (16-OHE1) pathways produce more potent and potentially problematic metabolites.

Phase II detoxification then takes these intermediate metabolites and further neutralizes them through processes like methylation, sulfation, and glucuronidation, making them water-soluble and ready for excretion via bile into the gut. A successful dietary strategy aims to support both phases, with a particular emphasis on promoting the favorable 2-OHE1 pathway in Phase I and ensuring the efficiency of Phase II.

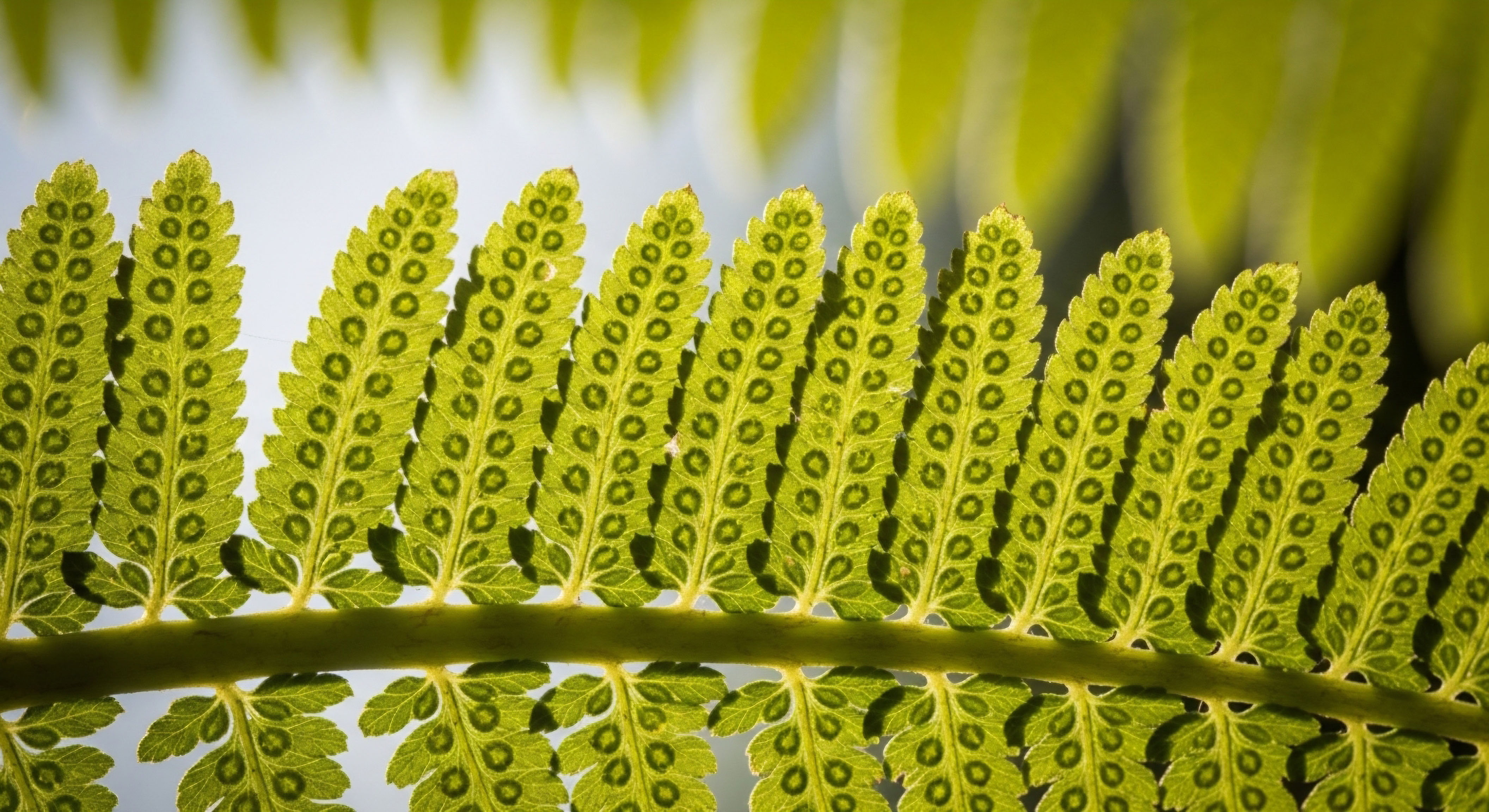

Cruciferous vegetables are clinical superstars in this regard. This family of plants, which includes broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, kale, and cabbage, is rich in a compound called glucobrassicin. When these vegetables are chopped or chewed, an enzyme called myrosinase is released, which converts glucobrassicin into indole-3-carbinol (I3C).

In the acidic environment of the stomach, I3C is then converted into several compounds, most notably 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM). Both I3C and DIM have been shown to upregulate the enzymes involved in the protective 2-OHE1 pathway, effectively shifting estrogen metabolism toward a less estrogenic and more beneficial state. Consuming at least one to two servings of cruciferous vegetables daily is a foundational recommendation for supporting healthy estrogen detoxification.

Phase II detoxification pathways are heavily dependent on specific nutrients to function correctly.

- Methylation ∞ This pathway, which uses the COMT (Catechol-O-methyltransferase) enzyme, requires B vitamins as essential cofactors. Foods rich in folate (leafy greens, lentils, avocado), vitamin B6 (chicken, fish, chickpeas), and vitamin B12 (animal products, nutritional yeast) are vital.

Magnesium also plays a crucial role in supporting COMT activity.

- Sulfation ∞ This pathway requires a steady supply of sulfur. Sulfur-rich foods include garlic, onions, shallots, eggs, and cruciferous vegetables.

- Glucuronidation ∞ This is a primary pathway for estrogen detoxification. Foods rich in glucaric acid, such as apples, oranges, and grapefruit, can support this process. Calcium-D-glucarate, a supplemental form, can inhibit the beta-glucuronidase enzyme in the gut, further supporting the elimination of estrogen.

What Is the Role of Phytoestrogens as Metabolic Modulators?

Phytoestrogens are plant-derived compounds that have a structural similarity to endogenous estrogen, allowing them to interact with estrogen receptors in the body. This interaction is key to their modulatory effect. The two main classes are isoflavones, found abundantly in soy products like tofu and tempeh, and lignans, which are concentrated in flaxseeds, sesame seeds, and whole grains.

These compounds function as natural selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs). They bind to estrogen receptors with a much weaker affinity than our body’s own potent estradiol. In a state of estrogen excess, these phytoestrogens can occupy the receptors, effectively blocking the more powerful endogenous estrogens from binding and exerting their strong proliferative effects.

This competitive inhibition can be highly beneficial for restoring balance. In a low-estrogen state, such as after menopause, their weak estrogenic activity can provide some mild, beneficial support. The metabolism of these compounds is also highly dependent on the gut microbiome.

For instance, gut bacteria convert plant lignans into the active compounds enterolactone and enterodiol, highlighting once again the centrality of gut health in hormonal modulation. A diet rich in these plant foods provides a sophisticated tool for fine-tuning the body’s response to its own hormonal signals.

Academic

The proposition that dietary modifications alone can restore estrogen metabolism equilibrium requires a nuanced, systems-level analysis. While the biochemical influence of nutrition on hepatic and enteric pathways is well-established and profound, the human biological system operates within a complex web of genetic predispositions, environmental exposures, and interconnected physiological networks.

To assert that diet is a universally sufficient monotherapy is to overlook this complexity. A more precise clinical perspective frames diet as the non-negotiable foundation of hormonal health, a powerful intervention whose ultimate success can be constrained by an individual’s unique biological context.

In this section, we will explore these constraints, viewing estrogen metabolism through the lenses of genomics, toxicology, and systems biology to define the boundaries of dietary efficacy and understand when it must be integrated into a broader therapeutic strategy.

The Limits of Dietary Intervention Genetic and Environmental Factors

An individual’s genetic blueprint can significantly influence the efficiency of their estrogen detoxification pathways, creating a predisposition that diet can modulate but may not entirely overcome. A prime example is found in single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the gene that codes for the Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) enzyme.

COMT is a critical Phase II liver enzyme responsible for methylating catechol estrogens, a key step in their neutralization. The Val158Met polymorphism, for instance, results in a version of the COMT enzyme with significantly reduced activity, slowing the clearance of potent estrogen metabolites.

An individual with this “slow COMT” genotype may have a genetically throttled capacity for estrogen methylation. While a diet rich in methyl donors (B vitamins, magnesium) is critically important for them, it may not be sufficient to compensate for a 40-50% reduction in enzyme function, especially under conditions of high estrogen production or exposure. In such cases, the system’s capacity is inherently limited, and an accumulation of estrogen can persist despite optimal dietary support.

Furthermore, we exist in an environment saturated with endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), or xenoestrogens. These compounds, found in plastics (BPA, phthalates), pesticides, industrial chemicals, and personal care products, mimic the structure of estrogen and can bind to its receptors, disrupting normal hormonal signaling. They place an enormous burden on the body’s detoxification systems.

The liver must process not only endogenous hormones but also this constant influx of foreign hormonal mimics. This can saturate the detoxification pathways, creating a bottleneck. Even a diet perfectly optimized for liver support can be overwhelmed by a high toxicant load.

The detoxification machinery is finite; when it is occupied with clearing xenoestrogens, its capacity to manage endogenous estrogen is compromised, leading to recirculation and accumulation. Therefore, a comprehensive strategy must include both dietary support and a concerted effort to minimize exposure to these environmental toxicants. For some individuals, the cumulative burden may necessitate clinical detoxification protocols that go beyond standard dietary approaches.

| Factor | Description | Clinical Implication | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Polymorphisms | Variations in genes encoding for detoxification enzymes. | Can create inherent limitations in metabolic capacity that diet may not fully overcome. | Slow COMT (Val158Met) polymorphism reduces estrogen methylation efficiency, predisposing to estrogen dominance. |

| Xenoestrogen Exposure | Environmental chemicals that mimic estrogen and disrupt hormonal function. | High toxicant load can saturate and overwhelm the liver’s detoxification pathways. | Chronic exposure to BPA from plastics competes with endogenous estrogen for detoxification, increasing overall estrogenic burden. |

| Gut Dysbiosis | An imbalance in the gut microbiome, often characterized by low diversity. | Leads to increased beta-glucuronidase activity, causing estrogen reabsorption. | A history of antibiotic use or a low-fiber diet can decimate beneficial microbes, leading to a dysfunctional estrobolome. |

| Systemic Inflammation | Chronic, low-grade inflammation from various sources. | Inflammatory cytokines can impair liver function and disrupt endocrine signaling. | A diet high in processed foods and refined sugars promotes inflammation, which can hinder the liver’s ability to metabolize hormones. |

A Systems Biology Perspective on Hormonal Equilibrium

Estrogen metabolism does not occur in a vacuum. It is deeply interconnected with the body’s other major regulatory systems, particularly the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs the stress response, and the thyroid axis. Chronic stress, whether psychological or physiological, leads to sustained high levels of cortisol.

This has significant downstream consequences for hormonal balance. The “pregnenolone steal” is a classic example of this interplay. Pregnenolone is a precursor hormone from which both cortisol and sex hormones like progesterone and DHEA are made. Under chronic stress, the body prioritizes cortisol production, shunting pregnenolone away from the pathways that produce sex hormones.

This can lead to lower progesterone levels, creating a state of relative estrogen dominance even if estrogen production itself is normal. The elevated cortisol also directly impairs liver detoxification and can negatively impact gut health, further compromising estrogen clearance. In this scenario, a diet aimed at balancing estrogen will be less effective if the underlying HPA axis dysfunction and chronic stress are not also addressed through lifestyle modifications, adaptogenic support, or other targeted interventions.

Similarly, thyroid function is intrinsically linked to estrogen. Thyroid hormone is necessary for the proper function of liver cells and the synthesis of detoxification enzymes. Hypothyroidism, or even subclinical low thyroid function, can slow down both Phase I and Phase II estrogen detoxification.

Conversely, excess estrogen can increase levels of thyroid-binding globulin (TBG), which binds to thyroid hormone and reduces the amount of free, active thyroid hormone available to the cells. This creates a vicious cycle where high estrogen can suppress thyroid function, and low thyroid function can worsen estrogen dominance.

A purely dietary approach focused on estrogen may fail if an underlying thyroid imbalance is the primary driver of the problem. A systems biology viewpoint demands that we assess and support these interconnected axes concurrently.

When Diet Becomes a Foundational Adjunct to Clinical Protocols

When the biological burden from genetic factors, xenoestrogen exposure, or severe systemic imbalances exceeds the restorative capacity of diet alone, clinical interventions become necessary. In these situations, diet transitions from a potential monotherapy to an essential adjunctive therapy. Its role is to create a biological terrain that maximizes the efficacy and safety of the clinical protocol.

For instance, in a male patient undergoing Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), a common concern is the aromatization of testosterone into estradiol. While a medication like Anastrozole is often prescribed to block the aromatase enzyme, a diet rich in cruciferous vegetables can provide a complementary mechanism of support by enhancing the clearance of estrogen through the liver’s 2-OHE1 pathway.

This creates a multi-pronged approach, using a pharmaceutical to block production and nutrition to enhance elimination. This integrated strategy can often allow for lower medication doses, reducing the potential for side effects and supporting the body’s intrinsic metabolic pathways.

For a perimenopausal woman experiencing significant symptoms, low-dose hormone therapy may be indicated to restore physiological stability. A supportive diet is critical for the success of this protocol. By ensuring robust gut health and efficient liver detoxification, the body is better able to metabolize and excrete the administered hormones, preventing their accumulation and minimizing risks.

The diet becomes the foundation that ensures the therapeutic intervention is both effective and well-tolerated. This perspective moves beyond the “diet versus drugs” dichotomy. It recognizes that the most sophisticated clinical approach involves leveraging diet to optimize the body’s innate systems, allowing targeted clinical therapies to work more effectively and safely. The goal is to use the least invasive, most effective intervention required, and a precisely formulated diet is always the first and most fundamental step in that process.

References

- Baker, J. M. Al-Nakkash, L. & Herbst-Kralovetz, M. M. (2017). Estrogen-gut microbiome axis ∞ Physiological and clinical implications. Maturitas, 103, 45 ∞ 53.

- Kwa, M. Plottel, C. S. Blaser, M. J. & Adams, S. (2016). The Estrobolome ∞ The Gut Microbiome and Estrogen. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 108(8), djw024.

- Sales, K. J. & Jabbour, H. N. (2003). Cyclooxygenase-2 and PGE2 receptor EP2 and EP4 signaling in human endometrial adenocarcinoma ∞ a mechanism for estrogen-independent tumor progression. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 88(5), 2277-2285.

- Lord, R. S. & Bralley, J. A. (2008). Laboratory evaluations for integrative and functional medicine. Metametrix Institute.

- Minich, D. M. & Jones, C. (2019). Optimizing Estrogen Detox. Metagenics Institute LIVE.

- Bradlow, H. L. Telang, N. T. Sepkovic, D. W. & Osborne, M. P. (1996). 2-hydroxyestrone ∞ the ‘good’ estrogen. Journal of endocrinology, 150 Suppl, S259 ∞ S265.

- Tsuchiya, Y. Nakajima, M. Kyo, S. Kanaya, T. Inoue, M. & Yokoi, T. (2005). Human CYP1B1 is regulated by estradiol via estrogen receptor-alpha. Cancer research, 65(18), 8496-8503.

- Hodges, R. E. & Minich, D. M. (2015). Modulation of Metabolic Detoxification Pathways Using Foods and Food-Derived Components ∞ A Scientific Review with Clinical Application. Journal of nutrition and metabolism, 2015, 760689.

- Patel, S. Homaei, A. Raju, A. B. & Meher, B. R. (2018). Estrogen ∞ A master regulator of the soul. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 13(1), 1-10.

- Adlercreutz, H. & Mazur, W. (1997). Phyto-oestrogens and Western diseases. Annals of medicine, 29(2), 95 ∞ 120.

Reflection

You have now journeyed through the intricate world of estrogen metabolism, from the fundamental roles of your liver and gut to the nuanced interplay of your genes and environment. This knowledge is more than a collection of scientific facts; it is a lens through which you can view your own body with greater clarity and understanding.

The symptoms you experience are not isolated events but chapters in a larger biological story. The fatigue, the mood swings, the physical changes ∞ they all speak a language that you are now better equipped to interpret. Consider the daily choices you make, particularly the foods you place on your plate. See them not as mere calories, but as potent biological information that directly instructs your cells, your microbiome, and your detoxification systems.

This understanding is the true starting point. The path forward is one of self-inquiry and observation. How does your body respond when you intentionally increase your intake of fiber-rich vegetables? What shifts do you notice when you prioritize cruciferous vegetables or incorporate fermented foods into your meals?

Your personal experience, informed by this clinical knowledge, becomes your most valuable guide. This process of tuning in, of connecting what you eat with how you feel, is the essence of reclaiming your health. The ultimate goal is to cultivate a deep partnership with your own physiology, a partnership built on a foundation of scientific literacy and profound self-awareness.

This knowledge empowers you to ask better questions and to engage with healthcare professionals as an informed collaborator in your own wellness journey. The potential for vitality is already within you; you are now learning how to unlock it.

Glossary

estrogen metabolism

gut microbiome

estrobolome

beta-glucuronidase

the estrobolome

gut health

cruciferous vegetables

indole-3-carbinol

estrogen detoxification

diindolylmethane

detoxification pathways

phytoestrogens

selective estrogen receptor modulators

xenoestrogens

hpa axis dysfunction

estrogen dominance