Fundamentals

You may feel a persistent sense of being out of sync, a subtle yet unshakeable disharmony within your own body. This experience, where energy seems elusive and vitality feels like a distant memory, is a valid and deeply personal reality for many.

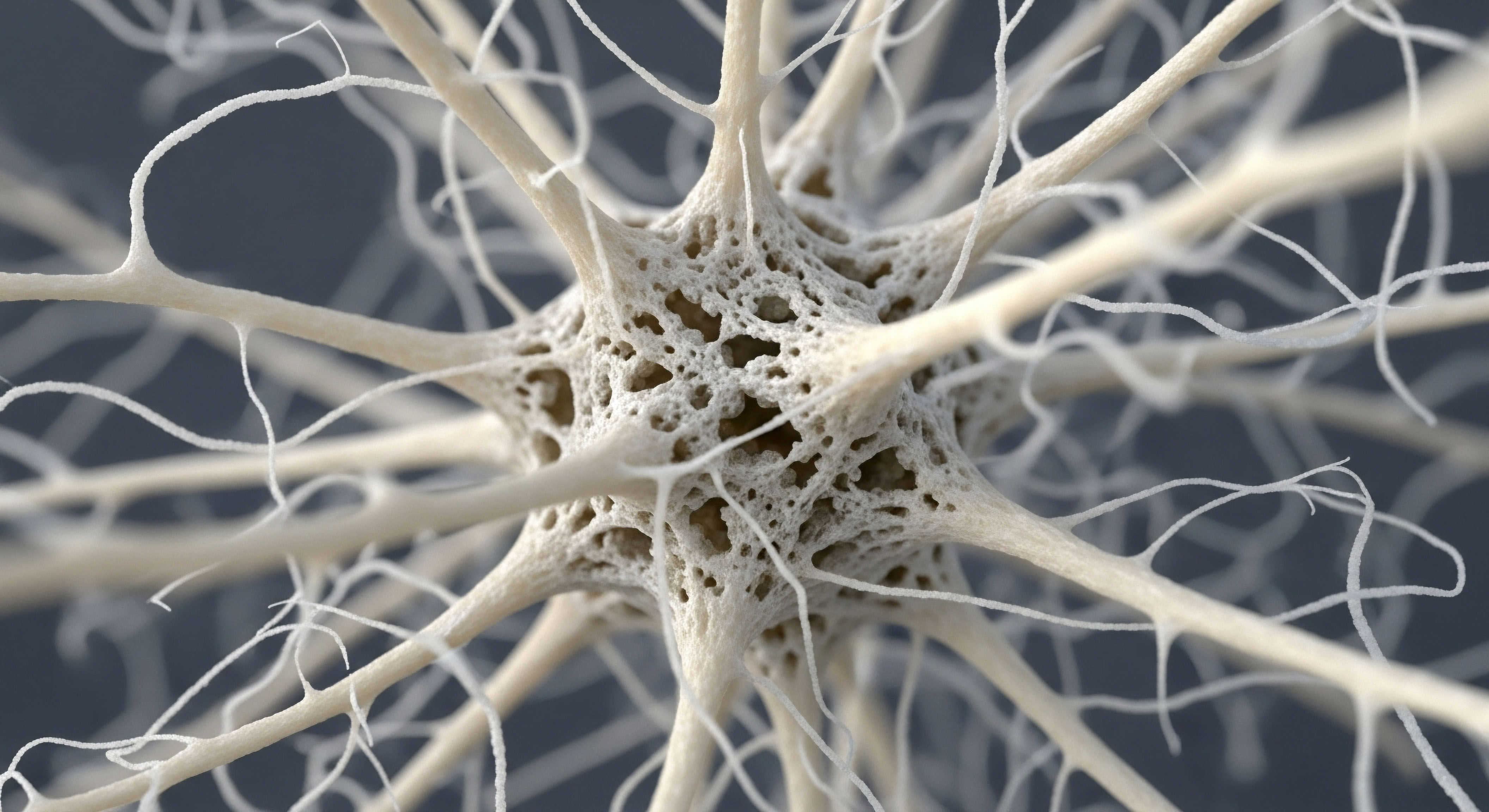

The journey to understanding this feeling begins not with a complex diagnosis, but with a simple acknowledgment of the body’s intricate communication network. At the very center of this network, acting as a primary regulator of your internal world, is your gut. It is here, within the vast ecosystem of your digestive tract, that the dialogue between your diet and your hormonal system takes place, influencing how you feel and function every single day.

Your body operates through a system of precise messages. Hormones are these messages, chemical couriers released from glands that travel throughout your bloodstream to deliver instructions to specific cells. For a message to be received, the target cell must have a corresponding receptor, a specialized protein structure that functions like a lock.

The hormone is the key, and only when the key fits the lock can the cell receive its instructions and perform its designated function. The sensitivity of these receptors determines how well the cell listens. High sensitivity means a small amount of hormone produces a strong response. Low sensitivity, or resistance, means the cell is becoming deaf to the message, requiring more and more hormone to achieve the same effect, a state that often precedes systemic dysfunction.

The Gut as a Communications Hub

The human gut is home to a complex and dynamic community of trillions of microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiota. This internal ecosystem is a metabolic powerhouse, performing functions that are essential for human health. It helps digest food, synthesizes vitamins, and plays a critical role in training and modulating your immune system.

Crucially, this microbial community is in constant communication with your endocrine system. The food you consume directly feeds this community, and in return, the microbes produce a vast array of compounds that enter your circulation and speak directly to your cells, including influencing the sensitivity of your hormone receptors.

Think of your gut microbiota as a vast signal-processing center. It takes the raw data from your diet and translates it into chemical signals that the rest of your body can understand. When this microbial community is balanced and diverse, it produces signals that promote health and maintain clear communication.

A state of imbalance, known as dysbiosis, results in distorted or inflammatory signals, disrupting this delicate hormonal conversation and contributing to the very symptoms of fatigue, mood shifts, and metabolic changes you may be experiencing.

How Diet Shapes the Hormonal Conversation

Dietary interventions are powerful because they directly alter the composition and function of your gut microbiota. By choosing specific foods, you are selectively cultivating certain types of bacteria and influencing the signals they produce. This is the foundational principle behind using diet to modulate hormone receptor sensitivity. Two key examples illustrate this connection with clarity.

Estrogen and the Estrobolome

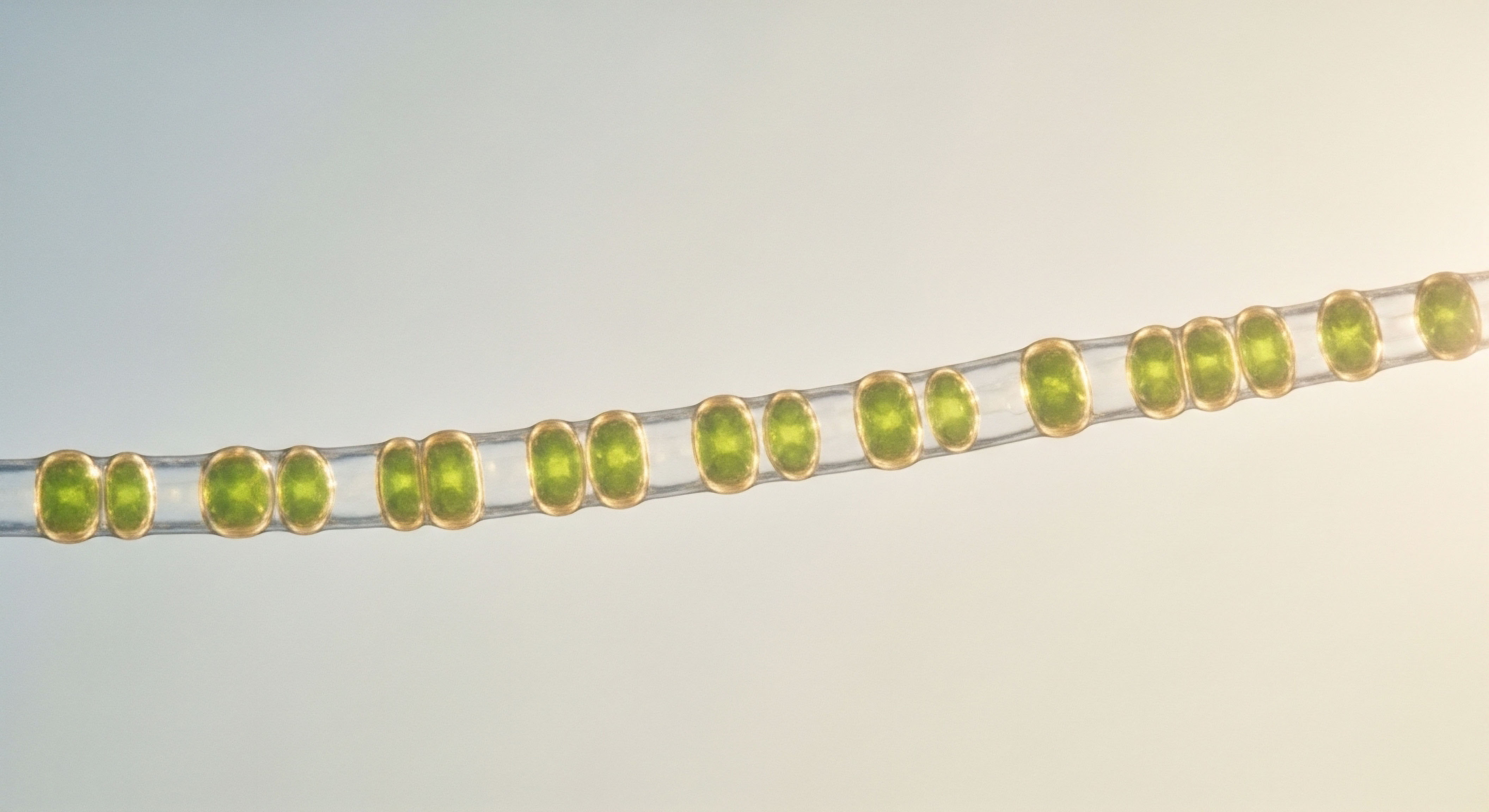

The gut contains a specific collection of bacteria with genes capable of metabolizing estrogens, a collection collectively termed the “estrobolome.” These bacteria produce an enzyme called β-glucuronidase. In the liver, estrogens are packaged for removal from the body through a process called glucuronidation.

Once these packaged estrogens reach the intestine, the β-glucuronidase produced by certain gut microbes can unpackage them, allowing them to be reabsorbed back into circulation. A diet that promotes a healthy estrobolome helps maintain normal estrogen levels. Conversely, an imbalanced gut can lead to either an excess or a deficiency of this enzyme activity, disrupting estrogen balance and affecting the sensitivity of estrogen receptors throughout the body.

Insulin and Inflammation

Insulin is the hormone that instructs your cells to take up glucose from the blood for energy. Insulin resistance, a state of dulled sensitivity in the insulin receptors, is a central feature of metabolic disease. An unhealthy gut microbiome, often fueled by diets high in processed foods and low in fiber, can compromise the integrity of the gut lining.

This allows inflammatory molecules from bacteria, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), to leak into the bloodstream. This low-grade systemic inflammation directly interferes with insulin receptors, making them less responsive to insulin’s signal. Your dietary choices, therefore, have a direct impact on the level of inflammation that can either protect or impair your metabolic health.

Your dietary choices directly cultivate the gut ecosystem that regulates the clarity and effectiveness of your body’s hormonal signals.

Understanding this connection is the first step toward reclaiming your biological vitality. The symptoms you experience are not isolated events; they are data points indicating a breakdown in communication. By addressing the health of your gut through targeted dietary strategies, you can begin to restore the integrity of this communication network, improve the sensitivity of your hormone receptors, and guide your body back toward a state of functional harmony.

This is a journey of biological restoration, moving from a state of internal noise to one of clear, coherent signaling.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding that diet influences hormones, we can examine the specific biological mechanisms through which these interactions occur. The conversation between your gut and your endocrine system is not abstract; it is a concrete biochemical process mediated by distinct molecules and cellular pathways.

By dissecting these pathways, we can appreciate how targeted dietary interventions can serve as precise tools to recalibrate hormone receptor sensitivity, particularly for critical hormones like insulin and estrogen. The focus shifts from general wellness to a protocol-driven approach aimed at producing measurable physiological change.

Dietary Fiber the Fuel for Beneficial Signaling

Dietary fiber is a primary modulator of the gut-hormone axis. It is indigestible by human enzymes, passing through to the colon where it becomes the principal food source for the microbiota. The fermentation of fiber by specific bacterial phyla produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), primarily acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These molecules are far more than simple metabolic byproducts; they are potent signaling molecules that exert systemic effects on host physiology.

SCFAs and Metabolic Receptor Sensitivity

SCFAs directly enhance insulin sensitivity through several interconnected mechanisms. They serve as ligands for G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), such as GPR41 and GPR43, which are expressed on various cell types, including the enteroendocrine L-cells of the gut lining. The activation of these receptors by SCFAs triggers the release of key satiety and metabolic hormones:

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) ∞ This hormone enhances insulin secretion from the pancreas in response to glucose, suppresses glucagon release, slows gastric emptying, and promotes a feeling of fullness. By stimulating GLP-1, SCFAs improve glucose tolerance and directly support the function of the insulin system.

- Peptide YY (PYY) ∞ Also released from L-cells upon SCFA stimulation, PYY travels to the brain where it acts on the hypothalamus to reduce appetite and food intake. This helps regulate energy balance and prevent the metabolic overload that can contribute to insulin resistance.

Butyrate, in particular, also serves as the primary energy source for the cells lining the colon (colonocytes), strengthening the gut barrier. A robust gut barrier is essential for preventing the translocation of inflammatory molecules into the bloodstream, a key driver of insulin resistance.

Gut Permeability and Inflammatory Crosstalk

A diet low in fiber and high in saturated fats and processed sugars can negatively alter the gut microbiota, leading to a condition of increased intestinal permeability, often referred to as “leaky gut.” In this state, the tight junctions between the cells of the intestinal lining loosen, allowing bacterial components to pass into circulation. The most studied of these is lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria.

LPS and Metabolic Endotoxemia

The chronic presence of elevated LPS in the bloodstream is termed metabolic endotoxemia. This condition is a potent trigger for systemic, low-grade inflammation. LPS binds to a receptor complex on immune cells and other tissues known as Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). The activation of TLR4 initiates a cascade of inflammatory signaling that directly interferes with hormone receptor function.

Chronic low-grade inflammation, often originating from gut dysbiosis, is a primary antagonist of sensitive and responsive hormone receptors.

For insulin receptors, this interference is direct and debilitating. The inflammatory pathways activated by LPS, such as the JNK and NF-κB pathways, lead to the phosphorylation of the insulin receptor substrate (IRS-1) on serine residues. This alteration prevents the normal downstream signaling required for glucose uptake, effectively creating a state of insulin resistance at the cellular level. This means that even in the presence of adequate insulin, the cell cannot properly hear the signal.

How Can We Modulate Gut Health for Hormone Sensitivity?

Improving hormone receptor sensitivity through gut modulation involves a strategic dietary approach aimed at increasing SCFA production, strengthening the gut barrier, and reducing the drivers of metabolic endotoxemia.

Table of Dietary Modulators and Their Mechanisms

| Dietary Component | Primary Mechanism of Action | Key Food Sources | Impact on Hormone Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soluble Fiber |

Fermented by gut bacteria into SCFAs (butyrate, propionate, acetate). Increases production of GLP-1 and PYY. |

Oats, barley, nuts, seeds, beans, lentils, apples, citrus fruits. |

Directly improves insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism. Promotes satiety, reducing metabolic load. |

| Insoluble Fiber |

Adds bulk to stool, promoting regularity and reducing transit time. This limits the interaction of potential toxins with the gut lining. |

Whole grains, nuts, cauliflower, green beans, potatoes. |

Indirectly supports gut health and reduces the potential for inflammatory triggers to cross the gut barrier. |

| Polyphenols |

Act as antioxidants and have a “prebiotic-like” effect, promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria (e.g. Bifidobacteria, Lactobacillus) and inhibiting pathogens. |

Berries, dark chocolate, tea, coffee, red wine, olive oil, various vegetables. |

Reduces oxidative stress and inflammation, thereby protecting receptor function. Shifts microbiota toward a less inflammatory profile. |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids |

Precursors to anti-inflammatory signaling molecules (resolvins, protectins). Help maintain cell membrane fluidity, which is important for receptor function. |

Fatty fish (salmon, mackerel, sardines), flaxseeds, chia seeds, walnuts. |

Directly counters the inflammatory cascades (e.g. from LPS) that cause receptor desensitization. |

A clinical strategy would involve systematically increasing the intake of these beneficial components while simultaneously reducing the intake of foods known to promote dysbiosis and gut permeability, such as highly processed foods, refined sugars, and certain saturated and trans fats.

This dual approach starves the problematic bacteria while feeding the beneficial ones, fundamentally shifting the gut environment from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory and metabolically supportive state. This is not merely “eating healthy”; it is a targeted intervention to restore a fundamental biological communication system.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of hormone receptor sensitivity requires an examination of the molecular crosstalk between microbial metabolites, immune signaling pathways, and the cellular machinery that governs receptor expression and function. The gut-hormone axis is regulated by a complex interplay of factors where dietary substrates are transformed by the microbiota into bioactive compounds that can trigger profound systemic endocrine and metabolic effects.

We will focus specifically on the mechanistic chain of events initiated by diet-induced metabolic endotoxemia and its direct consequences on insulin and steroid hormone receptor signaling at the molecular level.

The Molecular Pathophysiology of Metabolic Endotoxemia

Metabolic endotoxemia is characterized by a two- to three-fold chronic increase in circulating lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a concentration sufficient to initiate a low-grade inflammatory state without inducing overt sepsis. This condition is frequently driven by a “Western” dietary pattern, high in saturated fats and refined carbohydrates and low in fermentable fiber.

Such a diet alters the gut microbial composition, favoring the growth of Gram-negative bacteria and compromising the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier. Increased intestinal permeability allows for the translocation of LPS from the gut lumen into systemic circulation.

Once in circulation, LPS is bound by LPS-binding protein (LBP) and primarily interacts with the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) complex, which is expressed on immune cells (e.g. macrophages) as well as on metabolically active tissues, including adipocytes, hepatocytes, and skeletal muscle cells. The activation of TLR4 initiates two principal downstream signaling cascades:

- The MyD88-dependent pathway ∞ This pathway rapidly activates transcription factors such as nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1). This leads to the transcriptional upregulation and subsequent secretion of a suite of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β).

- The TRIF-dependent pathway ∞ This pathway is activated later and leads to the production of type I interferons, contributing to the inflammatory milieu.

Direct Cytokine-Mediated Interference with Insulin Receptor Signaling

The systemic inflammation resulting from metabolic endotoxemia is a primary driver of insulin resistance. The cytokine TNF-α, in particular, is a potent inhibitor of insulin signaling. Its mechanism of action is precise and well-characterized:

- Inhibitory Serine Phosphorylation ∞ Insulin signaling is propagated through the tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) by the activated insulin receptor kinase. TNF-α, acting through its own receptor, activates intracellular kinases, most notably c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and IκB kinase (IKK). These kinases, in turn, phosphorylate IRS-1 on specific serine residues (e.g. Ser307).

- Functional Consequences ∞ Serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 has two detrimental effects. First, it sterically hinders the ability of the insulin receptor to bind and phosphorylate IRS-1 on its critical tyrosine residues. Second, it can target IRS-1 for proteolytic degradation. The result is a severe attenuation of the insulin signal, preventing the translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters to the cell membrane and causing cellular insulin resistance.

This pathway demonstrates a direct molecular link from a diet-induced gut microbial shift to a specific post-translational modification that impairs the function of a key component in the insulin signaling cascade.

Metabolic endotoxemia initiates a specific inflammatory cascade that directly phosphorylates and inactivates key substrates in the insulin signaling pathway.

What Are the Implications for Steroid Hormone Receptors?

The influence of gut-derived inflammation extends beyond metabolic hormones. Steroid hormone signaling, crucial for reproductive health, bone density, and cognitive function, is also susceptible to modulation by these inflammatory pathways.

The Estrobolome and Receptor Activation

The concept of the “estrobolome” describes the aggregate of enteric bacterial genes whose products can metabolize estrogens. The key enzyme, β-glucuronidase, deconjugates estrogens that have been inactivated in the liver, allowing them to be reabsorbed and reactivate estrogen receptors (ER-α and ER-β).

Dysbiosis can alter the population of β-glucuronidase-producing bacteria (e.g. certain species of Clostridium and Bacteroides), thereby modifying the pool of circulating, active estrogens. A high-fiber, polyphenol-rich diet tends to lower β-glucuronidase activity, promoting estrogen excretion and potentially reducing the risk of hormone-sensitive malignancies.

Inflammation and Nuclear Receptor Crosstalk

The pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB, heavily activated by the LPS-TLR4 axis, can engage in direct antagonistic crosstalk with nuclear hormone receptors, including the estrogen receptor. This can occur through several mechanisms:

- Competition for Co-activators ∞ Both NF-κB and nuclear receptors like ER-α require a limited pool of transcriptional co-activators (e.g. CREB-binding protein/p300) to initiate gene expression. In a high-inflammatory state, the sustained activation of NF-κB can sequester these co-activators, making them less available for the hormone receptor, thereby dampening hormone-dependent gene transcription.

- Direct Repression ∞ Activated NF-κB can directly bind to and repress the promoter regions of certain hormone-responsive genes, and vice-versa. This reciprocal inhibition means that chronic inflammation can suppress normal endocrine function.

Table of Microbial Metabolites and Receptor Interactions

| Microbial Metabolite/Component | Origin/Dietary Influence | Host Receptor/Target | Molecular Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butyrate (SCFA) |

Fermentation of dietary fiber (e.g. resistant starch, inulin). |

GPR41/43; HDAC inhibitor. |

Stimulates GLP-1/PYY release; epigenetically modifies gene expression, enhancing gut barrier integrity. |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) |

Gram-negative bacteria; increased by high-fat, low-fiber diets. |

TLR4 complex. |

Activates NF-κB and JNK pathways, leading to inflammatory cytokine production and serine phosphorylation of IRS-1. |

| Secondary Bile Acids |

Bacterial modification of primary bile acids from the liver. |

FXR, TGR5. |

Modulates glucose and lipid metabolism. TGR5 activation on L-cells can also stimulate GLP-1 secretion. |

| Indole Derivatives |

Bacterial metabolism of dietary tryptophan. |

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR). |

Influences immune cell function (e.g. IL-22 production), strengthening the gut barrier and modulating local inflammation. |

In conclusion, dietary interventions represent a clinically relevant strategy for modulating hormone receptor sensitivity by targeting the gut microbiota. A diet rich in fermentable fibers and polyphenols cultivates a microbial ecosystem that produces anti-inflammatory and metabolically favorable compounds like SCFAs.

This strengthens the gut barrier, reduces LPS translocation, and consequently mitigates the chronic inflammatory signaling that directly desensitizes insulin and other hormone receptors. Conversely, a diet that promotes dysbiosis establishes a self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation and endocrine dysfunction, providing a clear, systems-biology rationale for the central role of gut health in personalized wellness protocols.

References

- Cani, Patrice D. et al. “Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance.” Diabetes, vol. 56, no. 7, 2007, pp. 1761-1772.

- Kwa, Maryam, et al. “The Intestinal Microbiome and Estrogen Receptor-Positive Female Breast Cancer.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 108, no. 8, 2016, djw029.

- Liang, H. et al. “Effect of Lipopolysaccharide on Inflammation and Insulin Action in Human Muscle.” PLoS ONE, vol. 8, no. 5, 2013, e63983.

- Cardona, Fernando, et al. “Benefits of polyphenols on gut microbiota and implications in human health.” Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, vol. 24, no. 8, 2013, pp. 1415-1422.

- Zengul, Ayse G. “Exploring The Link Between Dietary Fiber, The Gut Microbiota And Estrogen Metabolism Among Women With Breast Cancer.” UAB Digital Commons, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 2019.

- De Vadder, Filipe, et al. “Microbiota-generated metabolites in energy metabolism and inflammation.” Gastroenterology, vol. 146, no. 6, 2014, pp. 1507-1518.

- Heiman, Mark L. and Frank L. Greenway. “A healthy gut microbiome is a key to weight management.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, vol. 91, no. 7, 2016, pp. 930-943.

- Rastelli, Marion, et al. “Gut Microbiome and Cancer.” Cancer Treatment and Research, vol. 178, 2019, pp. 241-260.

- Cani, Patrice D. and Nathalie M. Delzenne. “The role of the gut microbiota in energy metabolism and metabolic disease.” Current Pharmaceutical Design, vol. 15, no. 13, 2009, pp. 1546-1558.

- Duenas, M. et al. “A survey of modulation of gut microbiota by dietary polyphenols.” BioMed Research International, vol. 2015, 2015, Article ID 850902.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a biological and chemical framework for understanding the connection between what you eat and how you feel. It translates the subjective experience of hormonal imbalance into a series of objective, modifiable processes. The knowledge that the sensitivity of your cellular receptors can be influenced by the microbial ecosystem within you is a powerful starting point.

This is the foundation upon which a personalized health strategy is built. Your own body contains the data, and your daily choices provide the inputs. The path forward involves listening to that data with increasing clarity and making informed decisions that guide your internal systems toward coherence and vitality. The next step in this journey is a personal one, involving introspection on how these systems manifest in your unique experience of health.