Fundamentals

You feel it before you can name it. A persistent, low-grade fatigue that sleep doesn’t resolve. A subtle shift in your mood, a new difficulty in managing your weight, or a sense that your body’s internal rhythm is slightly off-key.

These experiences are valid, and they are often the first signals of a deeper conversation happening within your biology. Your body is communicating a disruption, and understanding the language of that system is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality. This journey begins in an unexpected place ∞ the complex, microscopic world within your gut.

At the center of this conversation is estrogen, a hormone you may associate primarily with female reproductive health, yet one that is a critical regulator of physiology in both men and women. It governs bone density, cardiovascular health, cognitive function, and body composition.

Proper hormonal function relies on a delicate balance, a symphony of production, utilization, and, most importantly, elimination. When this final step is compromised, the entire system can be thrown into disarray. The mechanism responsible for orchestrating this crucial exit of estrogen from the body is profoundly influenced by the health of your digestive tract.

The Life Cycle of Estrogen

To grasp the significance of gut health in hormonal balance, we must first trace the path estrogen takes through the body. Estrogen is produced primarily in the ovaries in pre-menopausal women, with smaller amounts produced by the adrenal glands and adipose (fat) tissue. In men and post-menopausal women, the adrenal glands and fat tissue are the main sources. Once produced, estrogen circulates in the bloodstream to carry out its many functions, binding to receptors in various tissues.

After it has fulfilled its purpose, it travels to the liver for processing. The liver acts as a sophisticated detoxification facility, converting the potent, active estrogen into weaker, inactive forms that can be safely eliminated. This occurs in two phases. Phase I metabolism, primarily driven by CYP450 enzymes, hydroxylates estrogens into various metabolites.

Phase II metabolism then “conjugates” these metabolites, attaching a molecule (like glucuronic acid) to them. This conjugation process effectively packages them up, rendering them water-soluble and ready for excretion. These conjugated, inactive estrogens are then sent with bile into the intestines, awaiting their final exit from the body through stool.

The Estrobolome the Gut’s Hormonal Gatekeeper

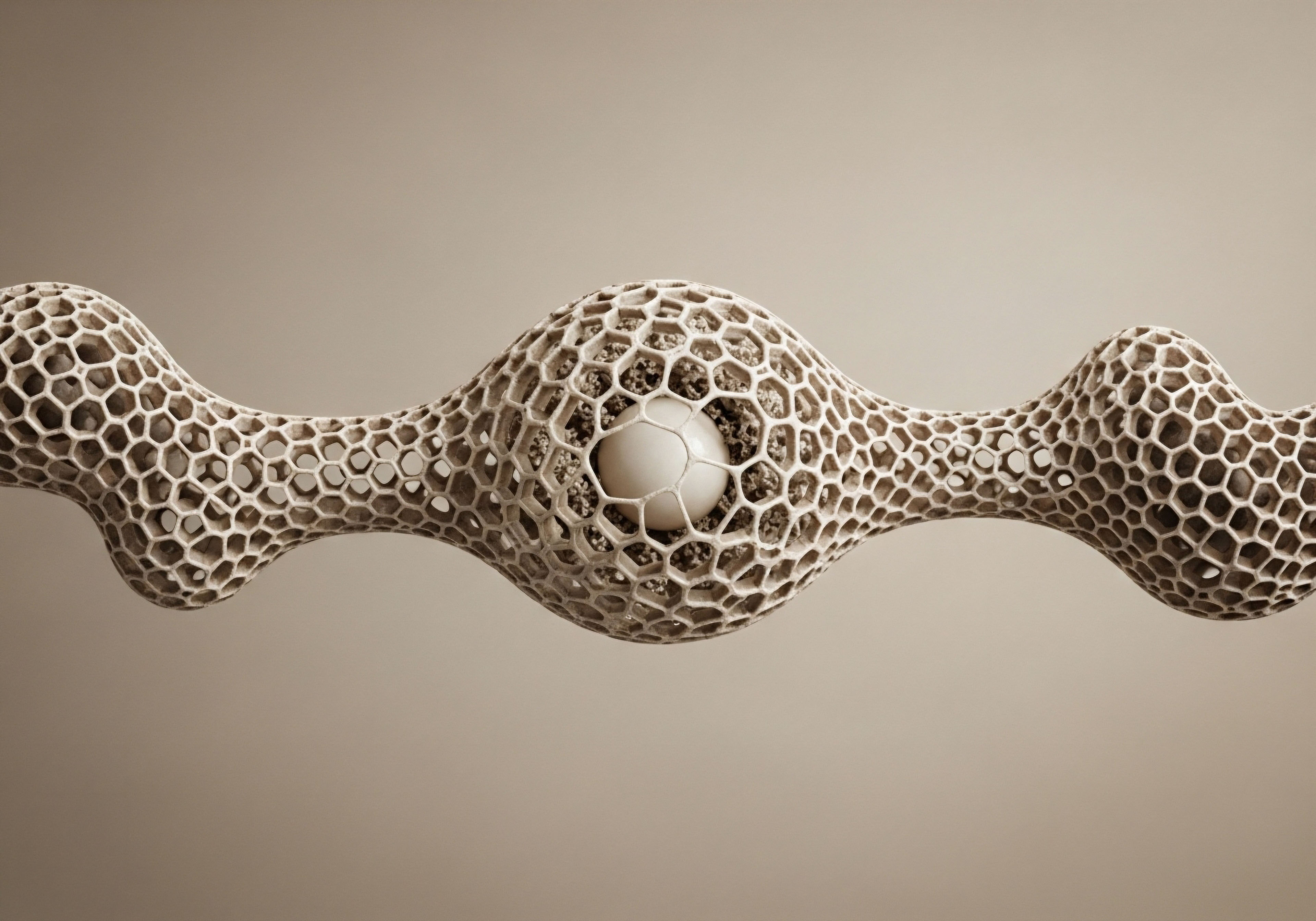

This is where the gut microbiome enters the narrative. Residing within your intestines is a specialized collection of bacteria with the unique capability of metabolizing estrogens. This microbial community is known as the estrobolome. These bacteria produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. The function of this enzyme is to break the bond that the liver worked so hard to create, “de-conjugating” the estrogen and reverting it back into its active form.

When the gut microbiome is in a state of healthy balance, it produces a baseline level of beta-glucuronidase, allowing for proper estrogen elimination while reabsorbing a small amount that may be needed. A healthy estrobolome ensures that the vast majority of “packaged” estrogen exits the body as planned.

However, an imbalanced gut microbiome, a state known as dysbiosis, can lead to an overproduction of beta-glucuronidase. This enzymatic overactivity essentially unpacks the estrogen that was meant for disposal. This newly freed, active estrogen is then reabsorbed back into the bloodstream, adding to the body’s total estrogen load. This process disrupts the carefully calibrated hormonal balance, contributing to a state of estrogen excess or “estrogen dominance.”

The community of microbes in your gut, the estrobolome, directly regulates how much estrogen is eliminated from your body or sent back into circulation.

This recirculation is not a minor biological footnote; it has profound implications for how you feel day-to-day. The symptoms of estrogen dominance ∞ which can include everything from premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and heavy periods in women to mood swings, weight gain, and fatigue in both sexes ∞ are often the direct result of this impaired elimination pathway.

Your lived experience of these symptoms is a direct reflection of this internal, microscopic struggle. Understanding this connection is the foundation upon which you can begin to build a strategy for restoring balance, using targeted dietary interventions to support your body’s innate ability to maintain hormonal equilibrium.

Intermediate

Recognizing the gut’s role in estrogen elimination shifts our perspective from one of passive suffering to one of active intervention. If an imbalanced estrobolome can drive hormonal disruption, then cultivating a healthy gut environment is a direct and powerful strategy for restoring order. Dietary choices are the primary tools we have to reshape this internal ecosystem.

Specific foods contain compounds that support the liver’s detoxification processes, provide the raw materials for a healthy gut lining, and directly influence the composition of the microbiome, thereby modulating beta-glucuronidase activity.

What Are the Most Effective Dietary Levers?

The path to hormonal balance through nutrition involves a multi-pronged approach. We must support the liver’s ability to package estrogen, provide the means to bind it in the gut, and ensure the gut environment favors elimination over reabsorption. This is achieved through a focus on fiber, specific phytonutrients from vegetables, and the introduction of beneficial bacteria and the foods that feed them.

The Critical Role of Dietary Fiber

Fiber is perhaps the most important dietary component for ensuring estrogen is properly excreted. It acts as a binding agent, trapping conjugated estrogens in the gut and carrying them out of the body in the stool. A low-fiber diet provides insufficient material to bind these estrogens, leaving them vulnerable to the de-conjugating action of beta-glucuronidase. There are two main types of fiber, and both are essential.

- Soluble Fiber ∞ This type of fiber dissolves in water to form a gel-like substance. It is fermented by colon bacteria, producing beneficial short-chain fatty acids like butyrate, which nourishes gut cells and strengthens the gut barrier. Sources include oats, barley, apples, citrus fruits, carrots, and legumes.

- Insoluble Fiber ∞ This type of fiber does not dissolve in water. It adds bulk to the stool, which promotes regular bowel movements. This increased transit time reduces the window of opportunity for beta-glucuronidase to reactivate estrogen. Sources include whole grains, nuts, seeds, and vegetables like cauliflower and green beans.

A daily intake of at least 25-35 grams of fiber from a variety of sources is a foundational step in supporting estrogen elimination. This consistent intake ensures that the machinery of excretion is always running efficiently.

Cruciferous Vegetables and Liver Optimization

Before estrogen even reaches the gut, the liver must process it effectively. Cruciferous vegetables contain unique compounds that directly support the liver’s Phase I and Phase II detoxification pathways. These vegetables are rich in a glucosinolate called glucobrassicin, which, when chewed and digested, produces a compound called indole-3-carbinol (I3C).

In the acidic environment of the stomach, I3C is converted into several metabolites, the most significant of which is diindolylmethane (DIM). Both I3C and DIM have been shown to favorably alter estrogen metabolism, promoting the production of “good” estrogen metabolites (like 2-hydroxyestrone) over more problematic ones (like 16-alpha-hydroxyestrone). By supporting the liver, these vegetables ensure that estrogen arrives in the gut in a form that is ready for efficient removal.

| Vegetable | Serving Suggestion | Key Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Broccoli & Broccoli Sprouts | Steamed or raw | Sulforaphane, I3C, DIM |

| Cauliflower | Roasted or riced | I3C, DIM |

| Brussels Sprouts | Roasted or shaved raw in salads | Glucosinolates, I3C |

| Kale | Lightly sautéed or in smoothies | I3C, DIM |

| Cabbage | Raw in coleslaw or fermented as sauerkraut | Glucosinolates, I3C |

Architects of the Estrobolome Probiotics and Prebiotics

To directly influence the estrobolome and curb the overproduction of beta-glucuronidase, we must focus on the health of the gut bacteria themselves. This is accomplished with probiotics and prebiotics.

- Probiotics ∞ These are live beneficial bacteria that, when consumed in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit. Fermented foods are excellent sources of probiotics. They introduce diverse strains of beneficial bacteria, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, which help to crowd out the less desirable microbes that produce excess beta-glucuronidase.

- Prebiotics ∞ These are types of dietary fiber that the human body cannot digest but that serve as food for beneficial gut bacteria. By feeding the good microbes, prebiotics help them to thrive and multiply, further shifting the balance of the microbiome in a favorable direction.

A diet rich in fiber, cruciferous vegetables, and fermented foods provides a powerful, synergistic strategy to support both liver detoxification and gut-level elimination of estrogen.

Consuming foods like yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and kimchi can help populate the gut with beneficial microbes. Simultaneously, including prebiotic-rich foods like garlic, onions, leeks, asparagus, and bananas provides the necessary fuel for these microbes to flourish.

What Impedes Proper Estrogen Elimination?

Just as certain foods can support estrogen elimination, other lifestyle factors can hinder it. Chronic alcohol consumption places a significant burden on the liver, competing for the same detoxification pathways that are needed to process estrogen. Exposure to xenoestrogens ∞ synthetic chemicals found in plastics (like BPA), pesticides, and personal care products ∞ can mimic estrogen in the body, adding to the overall hormonal load.

Furthermore, courses of antibiotics, while sometimes medically necessary, can disrupt the delicate balance of the gut microbiome, potentially altering the estrobolome for months. A comprehensive approach involves both adding supportive elements and removing disruptive ones.

Academic

A sophisticated understanding of hormonal health requires moving beyond dietary recommendations to examine the precise molecular mechanisms at play. The relationship between dietary inputs, the gut microbiome, and systemic estrogen levels is a complex interplay of enzymatic activity, microbial metabolism, and immune signaling. The estrobolome’s influence extends far beyond simple excretion; it is a critical node in the body’s entire endocrine network, capable of modulating inflammatory pathways and influencing the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.

The Estrobolome and Beta-Glucuronidase a Molecular Perspective

The term estrobolome refers to the aggregate of enteric bacterial genes whose products are capable of metabolizing estrogens. The key enzyme in this process, beta-glucuronidase, is produced by a range of bacteria, primarily within the Firmicutes phylum, including species of Clostridium and Escherichia. The enzymatic reaction itself is a hydrolysis event.

In the liver, estrogen metabolites are conjugated with glucuronic acid via the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) enzyme family. This creates a bulky, hydrophilic molecule that is readily excreted in bile. Once in the intestine, bacterial beta-glucuronidase cleaves this glucuronic acid moiety from the estrogen molecule. This deconjugation reverts the estrogen to a smaller, lipophilic form that can be reabsorbed through the intestinal epithelium into the portal circulation, ultimately re-entering systemic circulation.

The level of beta-glucuronidase activity in the gut is therefore a rate-limiting step for estrogen reabsorption. A microbiome characterized by a high abundance of beta-glucuronidase-producing bacteria creates a state of high enzymatic potential, leading to increased estrogen recirculation and a higher systemic estrogen burden. Conversely, a microbiome rich in fiber-fermenting bacteria and low in these specific enzyme producers facilitates more complete estrogen excretion.

How Does Gut Dysbiosis Influence Systemic Inflammation?

The consequences of gut dysbiosis are not confined to the gut lumen. An imbalanced microbiome, often coupled with a diet low in fiber and high in processed foods, can compromise the integrity of the intestinal barrier. This condition, often termed “leaky gut” or increased intestinal permeability, allows for the translocation of bacterial components from the gut into the bloodstream.

One of the most potent of these components is lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a major constituent of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria.

When LPS enters the circulation, it is recognized by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on immune cells, triggering a potent inflammatory cascade. This results in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. This low-grade, chronic systemic inflammation can have profound effects on the endocrine system.

It can disrupt insulin signaling, leading to insulin resistance. Crucially, it can also interfere with the sensitive feedback loops of the HPG axis. Inflammatory cytokines can suppress the release of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, which in turn reduces the secretion of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) from the pituitary. This disruption can affect ovarian function in women and testicular function in men, altering the production of endogenous sex hormones.

| Dietary Component | Microbial Impact | Physiological Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fiber (Inulin, Pectin) | Promotes growth of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. Increases production of short-chain fatty acids (butyrate). | Strengthens gut barrier integrity, reduces LPS translocation, lowers systemic inflammation, and decreases beta-glucuronidase activity. |

| Cruciferous Vegetables (I3C/DIM) | Modulates gut microbial composition. | Supports Phase I & II liver detox, promoting favorable 2-OH estrogen metabolites. Reduces substrate for problematic pathways. |

| Polyphenols (from berries, tea) | Act as prebiotics, promoting beneficial bacteria. Possess direct antioxidant effects. | Reduces oxidative stress, enhances microbial diversity, and may inhibit growth of pathogenic bacteria. |

| High-Saturated Fat / High-Sugar Diet | Promotes growth of Firmicutes and Proteobacteria. Decreases microbial diversity. | Increases intestinal permeability, elevates circulating LPS, drives chronic inflammation, and increases beta-glucuronidase activity. |

Integrating Gut Health into Hormonal Optimization Protocols

This systems-biology perspective has direct clinical applications for hormonal optimization therapies. A patient’s gut health status can significantly impact the efficacy and safety of these protocols.

The gut microbiome acts as an endocrine organ, and its health is a prerequisite for the success of any systemic hormonal therapy.

Consider a male patient undergoing Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT). A common challenge in TRT is managing the aromatization of testosterone into estradiol. This patient may be prescribed an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole to control estrogen levels.

If this patient also has gut dysbiosis with high beta-glucuronidase activity, his body is not only producing estrogen via aromatization but also reabsorbing it from the gut. This creates a much higher total estrogen load, potentially requiring higher or more frequent doses of Anastrozole, which carries its own set of potential side effects.

By implementing a dietary protocol to improve his gut health ∞ increasing fiber, adding cruciferous vegetables, and consuming fermented foods ∞ he could reduce the amount of estrogen being recirculated. This intervention could lower his systemic estrogen levels, potentially allowing for a reduction in his Anastrozole dosage and leading to a more stable and optimized hormonal state.

Similarly, for a perimenopausal woman experiencing significant fluctuations in estrogen, a gut-centric dietary approach can be a powerful adjunctive therapy. During perimenopause, the ovaries produce estrogen erratically. Improving the gut’s ability to efficiently clear estrogen can help to blunt the peaks of these fluctuations, leading to a reduction in symptoms like heavy bleeding or mood swings.

For a woman on low-dose hormone therapy, ensuring optimal gut-mediated elimination prevents the accumulation of exogenous hormones and supports the body’s ability to achieve a stable balance. The gut is a dynamic and modifiable variable that should be addressed as a foundational component of any sophisticated hormonal health strategy.

References

- Baker, J. M. Al-Nakkash, L. & Herbst-Kralovetz, M. M. “Estrogen-gut microbiome axis ∞ Physiological and clinical implications.” Maturitas, vol. 103, 2017, pp. 45-53.

- Ervin, S. M. Li, H. Lim, L. Roberts, L. R. & Gores, G. J. “The Estrobolome and Its Dysregulation in Disease.” Current Pathobiology Reports, vol. 7, no. 2, 2019, pp. 123-131.

- Kwa, M. Plottel, C. S. Blaser, M. J. & Adams, S. “The Intestinal Microbiome and Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 108, no. 8, 2016, djw029.

- “The Estrobolome ∞ How It Influences Hormone Health for Everyone.” A-LIGN, 11 Dec. 2024.

- “How to Support Estrogen Detoxification Naturally.” Stram Center for Integrative Medicine, 3 Apr. 2025.

- “The Gut-Hormone connection (Plus 5 Ways to Support).” Elix, Accessed 25 July 2025.

- “Hormones & Gut Health ∞ The Estrobolome & Hormone Balance.” The Marion Gluck Clinic, Accessed 25 July 2025.

Reflection

You have now traveled from the felt sense of imbalance to the intricate molecular pathways that govern your hormonal health. This knowledge provides a new lens through which to view your body ∞ not as a collection of disparate symptoms, but as an interconnected, intelligent system.

The information presented here is a map, detailing the profound connection between your gut, your liver, and your endocrine system. It illustrates how the food you choose is a form of biological communication, a direct message sent to the microbial allies within you.

The true power of this understanding is that it shifts the locus of control. It frames health as a dynamic process you can actively participate in. The question now becomes personal. What is your body communicating to you through its unique language of symptoms and sensations?

How might nurturing the foundation of your health ∞ the ecosystem within your gut ∞ change the conversation? This exploration is the first step. The path forward involves listening to your body with this new awareness and considering how to apply these principles to your own unique biology, creating a personalized strategy for lasting vitality.