Fundamentals

You feel it in your system. A subtle, persistent shift that leaves you questioning your own body’s reliability. It could be a change in your energy, your mood, your physical shape, or your mental clarity. This experience, this internal dissonance, is a valid and important signal.

It’s your biology communicating a change in its internal operating instructions. Often, this feeling points toward the complex world of your hormones, specifically the way your body manages the conversion and balance of potent molecules like estrogen.

The question of whether diet alone can steer this intricate process is a deeply personal one, because it speaks to a desire for agency over your own health. It is an inquiry into whether the very things we use to build and fuel our bodies can also be the primary tools to recalibrate them.

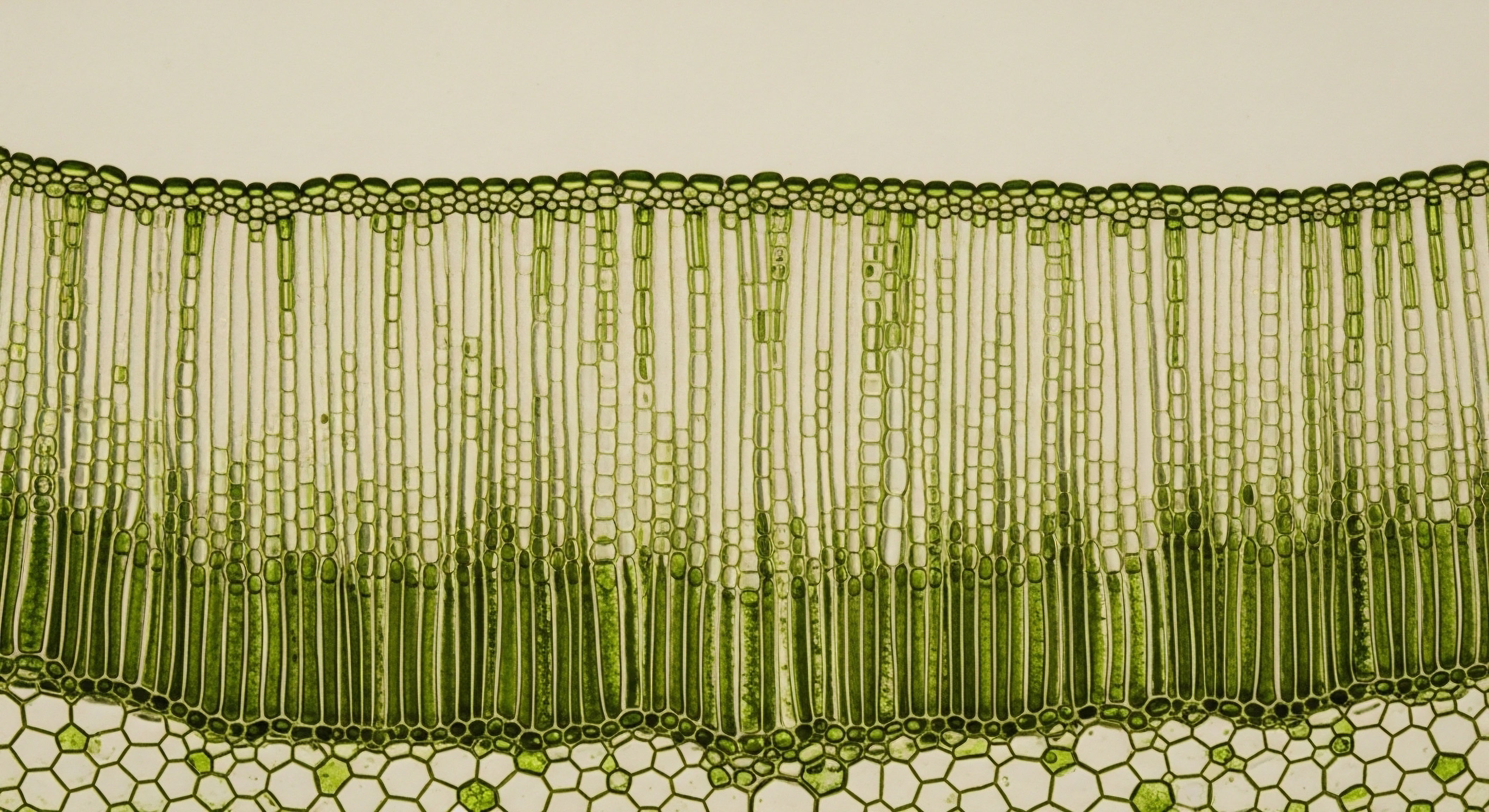

To begin this exploration, we must first understand the central mechanism at play. Your body contains a specific enzyme called aromatase. Think of it as a highly specialized biological factory worker. Its primary job is to take one type of hormone, an androgen like testosterone, and convert it into another type of hormone, an estrogen.

This process is not a flaw; it is a fundamental and necessary part of human physiology for both men and women. Estrogen is vital for cognitive function, bone health, cardiovascular integrity, and, in men, even for libido and sperm maturation. The system is designed to perform this conversion. The challenges arise when the activity of this aromatase Meaning ∞ Aromatase is an enzyme, also known as cytochrome P450 19A1 (CYP19A1), primarily responsible for the biosynthesis of estrogens from androgen precursors. “factory” becomes dysregulated, either working overtime or operating in tissues where it creates a localized surplus of estrogen.

The Concept of Hormonal Balance

The term “hormonal imbalance” often suggests a simple seesaw that has tipped too far one way. A more accurate picture is that of an ecosystem. A healthy ecosystem thrives on a dynamic equilibrium, where multiple factors interact to maintain stability. Your endocrine system functions similarly.

An imbalance, such as “estrogen dominance,” describes a state where the biological effects of estrogen are disproportionately high relative to other hormones, particularly progesterone in women or testosterone in men. This can happen in two primary ways. Your body might produce an excessive amount of estrogen, or your ability to properly metabolize and clear estrogen from the system might be impaired.

This is where the conversation about dietary intervention begins, as food directly influences both the production and the clearance pathways of these powerful chemical messengers.

Your body’s hormonal state is a dynamic ecosystem, where the goal is not static levels but a responsive, functional equilibrium.

What Are the Primary Dietary Levers?

When we consider managing estrogen conversion through While direct aromatase-inhibiting peptides are not established, Gonadorelin supports natural testicular function, and growth hormone secretagogues improve metabolic health, indirectly aiding estrogen balance during TRT. diet, we are looking at three distinct but interconnected areas of influence. Each represents a powerful lever that can be adjusted through conscious nutritional choices. Understanding these levers provides a clear framework for how food becomes an active participant in your hormonal health.

First, certain foods contain natural compounds that can directly interact with the aromatase enzyme, potentially modulating its activity. Second, your diet profoundly shapes the health of your gut microbiome. This internal ecosystem contains a specialized collection of bacteria, now known as the estrobolome, that plays a critical role in the final stages of estrogen metabolism Meaning ∞ Estrogen metabolism refers to the comprehensive biochemical processes by which the body synthesizes, modifies, and eliminates estrogen hormones. and elimination.

An unhealthy gut can lead to the reabsorption of estrogen that was meant to be excreted. Third, your overall metabolic health, particularly your body’s sensitivity to insulin and the amount of adipose (fat) tissue you carry, sets the stage for your hormonal environment.

Adipose tissue itself is a significant site of aromatase activity, meaning that metabolic dysfunction can directly fuel excess estrogen production. Each of these three pillars is uniquely responsive to dietary inputs, giving you a tangible way to influence your body’s hormonal machinery.

These principles form the foundation of using nutrition as a tool. They move the focus from simply eating “healthy” to eating strategically, providing your body with the specific raw materials it needs to support a more balanced and functional endocrine system. The table below outlines some key food groups and their primary area of influence on these pathways.

| Food Group | Primary Mechanism of Action | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cruciferous Vegetables | Supports liver detoxification pathways and provides compounds that modulate estrogen metabolism. | Broccoli, cauliflower, kale, Brussels sprouts. |

| High-Fiber Foods | Promotes healthy gut bacteria and ensures proper excretion of metabolized estrogens. | Legumes, whole grains, nuts, seeds, fruits, vegetables. |

| Phytoestrogen-Containing Foods | Contain plant-based compounds that can interact with estrogen receptors and modulate enzyme activity. | Flaxseed, soy (organic, whole), chickpeas. |

| Healthy Fats | Supports overall cellular health and helps reduce inflammation, which can drive hormonal imbalance. | Avocados, olive oil, nuts, seeds, fatty fish. |

| Lean Protein | Provides essential amino acids for liver function and helps stabilize blood sugar, reducing metabolic stress. | Fish, poultry, lentils, organic eggs. |

Intermediate

Building upon the foundational understanding of hormonal balance, we can now examine the specific biochemical interactions between dietary components and your endocrine system. This is where we translate broad nutritional principles into targeted actions. The goal is to understand how specific food choices can create a biological environment that favors healthy estrogen metabolism, working in concert with the body’s innate regulatory systems.

This knowledge is particularly relevant when considering how to support or augment clinical protocols, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy Meaning ∞ Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) is a medical treatment for individuals with clinical hypogonadism. (TRT), where managing estrogen conversion is a primary objective.

Nutritional Modulation of Aromatase Activity

The aromatase enzyme Meaning ∞ Aromatase enzyme, scientifically known as CYP19A1, is a crucial enzyme within the steroidogenesis pathway responsible for the biosynthesis of estrogens from androgen precursors. is the direct gateway for converting androgens to estrogens. Influencing its activity is a primary strategy for managing estrogen levels. While pharmaceutical aromatase inhibitors Managing aromatase activity is achievable by restoring the body’s metabolic health and reducing the inflammatory signals that drive it. like Anastrozole act by directly blocking this enzyme, certain dietary compounds appear to modulate its activity in a more subtle, systemic manner. These phytochemicals, or plant-based chemicals, are found in a wide variety of common foods.

Cruciferous vegetables, for example, are rich in a compound called indole-3-carbinol, which the body converts into Diindolylmethane (DIM). DIM supports healthy estrogen metabolism by influencing the way the liver processes estrogen, favoring the production of less potent estrogen metabolites over more powerful ones.

This action helps to shift the overall estrogenic load in the body towards a less stimulating state. Additionally, certain flavonoids found in foods like celery, parsley, and chamomile have demonstrated aromatase-inhibiting properties in laboratory studies. While consuming these foods is not equivalent to taking a pharmaceutical inhibitor, a diet consistently rich in these compounds contributes to an overall biochemical environment that is less conducive to excessive aromatase activity.

The Role of Phytoestrogens

Phytoestrogens, particularly lignans from flaxseed and isoflavones from soy, are often a source of confusion. Because of their structural similarity to human estrogen, they can bind to estrogen receptors. This has led to concerns about their potential to increase estrogenic effects. The reality of their function is more complex.

These plant-based compounds have a much weaker binding affinity for estrogen receptors than endogenous estrogen. In situations of high estrogen, they may act as competitive antagonists, blocking the more potent human estrogen from binding to its receptor. In situations of low estrogen, their weak binding may provide a mild estrogenic signal.

Furthermore, some phytoestrogens, like those found in red clover and licorice root, have been shown to possess aromatase-inhibiting properties themselves, adding another layer to their modulatory effects. A diet that includes these foods in whole, unprocessed forms can therefore be a valuable tool for supporting hormonal equilibrium.

The Estrobolome Your Gut’s Critical Role in Estrogen Clearance

The conversation about estrogen balance is incomplete without a thorough examination of the gut. After the liver processes estrogens to deactivate them, they are sent into the gut via bile for excretion. Here, a specialized community of gut microbes known as the estrobolome Meaning ∞ The estrobolome is the collection of gut bacteria that metabolize estrogens. takes center stage.

These bacteria produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. This enzyme can effectively “reactivate” the estrogen that was marked for removal, allowing it to be reabsorbed back into the bloodstream. An unhealthy gut microbiome, often characterized by low diversity and an overgrowth of certain bacteria, can produce excessive amounts of beta-glucuronidase. This leads to a constant re-circulation of estrogen, contributing significantly to a state of estrogen dominance even when initial production is normal.

A healthy gut microbiome is essential for the final, critical step of estrogen elimination from the body.

Dietary intervention is the single most powerful tool for shaping your estrobolome. The following strategies are key to promoting a gut environment that ensures proper estrogen clearance:

- Fiber Intake ∞ A high-fiber diet is paramount. Soluble and insoluble fiber from a wide variety of plant sources feeds beneficial gut bacteria, promotes regular bowel movements, and directly binds to excreted estrogen, ensuring its removal from the body. Aiming for a diverse intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and seeds is foundational.

- Probiotic-Rich Foods ∞ Fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and kimchi introduce beneficial bacteria into the gut, helping to maintain a healthy and diverse microbial community.

- Prebiotic Foods ∞ Prebiotics are types of fiber that specifically feed beneficial gut microbes. Foods like garlic, onions, asparagus, and bananas are excellent sources of prebiotics that help the “good” bacteria thrive.

- Limiting Processed Foods and Sugars ∞ Diets high in refined sugars and processed foods can promote the growth of less desirable bacteria, leading to gut dysbiosis and potentially higher levels of beta-glucuronidase activity.

Contextualizing Diet with Clinical Hormone Optimization

For an individual on a clinically supervised hormone optimization protocol, such as a man using Testosterone Cypionate for TRT, these dietary principles are not merely suggestions; they are integral components of a successful treatment plan. When testosterone is administered, the body’s natural response is to convert a portion of it to estrogen via the aromatase enzyme.

If this conversion is excessive, it can lead to side effects Meaning ∞ Side effects are unintended physiological or psychological responses occurring secondary to a therapeutic intervention, medication, or clinical treatment, distinct from the primary intended action. like water retention, mood changes, and gynecomastia. While an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole is often prescribed to control this, diet acts as a foundational support system.

A man on TRT who adopts a diet rich in cruciferous vegetables, high in fiber, and low in inflammatory processed foods is actively creating an internal environment that supports the goals of his therapy. Such a diet can help manage inflammation, support liver function for hormone processing, and promote healthy estrogen clearance through the gut.

This holistic approach may allow for a lower effective dose of pharmaceutical aromatase inhibitors, reducing the potential for side effects associated with excessive estrogen suppression. The diet becomes a synergistic partner to the clinical intervention, working to optimize the entire hormonal axis.

| Intervention Type | Mechanism of Action | Primary Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Aromatase Inhibitors (e.g. Anastrozole) | Direct, potent, and competitive blockade of the aromatase enzyme. | Clinically significant estrogen excess, often in the context of HRT or certain cancers. | Requires careful medical supervision to avoid excessive estrogen suppression. Potential for side effects like joint pain. |

| Nutritional Aromatase Modulators (e.g. DIM, flavonoids) | Subtle modulation of enzyme activity and support for metabolic pathways. | Foundational support for hormonal balance and as an adjunct to clinical therapy. | Effects are systemic and less potent than pharmaceuticals. Consistency is key. |

| Gut Health Optimization (e.g. High-Fiber Diet) | Modulates the estrobolome to ensure proper excretion of metabolized estrogen. | Essential for anyone with hormonal concerns, as it addresses the clearance side of the equation. | Benefits extend far beyond hormonal health, impacting immunity and inflammation. |

Academic

An academic appraisal of dietary interventions in the management of estrogen conversion Meaning ∞ Estrogen conversion refers to the biochemical processes through which the body synthesizes various forms of estrogen from precursor hormones or interconverts existing estrogen types. requires a shift from general principles to specific molecular mechanisms and systems-level interactions. The central question of whether diet alone can be sufficient is answered by dissecting the quantitative impact of nutrition on three critical physiological domains ∞ the genetic expression and function of the aromatase enzyme (CYP19A1), the endocrine activity of adipose tissue, and the complex interplay of the gut-liver-endocrine axis.

While dietary strategies are foundational for establishing a favorable biochemical environment, their efficacy as a sole intervention is constrained by an individual’s genetic predispositions, metabolic health status, and the presence of supraphysiological hormone levels from exogenous therapies.

Molecular Mechanisms of Dietary Aromatase Modulation

The human aromatase enzyme is encoded by the CYP19A1 Meaning ∞ CYP19A1 refers to the gene encoding aromatase, an enzyme crucial for estrogen synthesis. gene. Its expression is not uniform throughout the body; it is controlled by tissue-specific promoters. For instance, in the ovaries, aromatase expression is driven by the proximal promoter II, which is regulated by gonadotropins.

In peripheral tissues like adipose tissue Meaning ∞ Adipose tissue represents a specialized form of connective tissue, primarily composed of adipocytes, which are cells designed for efficient energy storage in the form of triglycerides. and in hormone-responsive breast cancer cells, expression is largely driven by promoters I.3 and a variant of promoter II. This tissue-specific regulation is a key concept, as it opens the possibility for targeted interventions.

Many natural compounds have been investigated for their ability to interact with this system. Flavonoids such as apigenin and chrysin, and isoflavones like genistein, have demonstrated aromatase inhibitory activity in in-vitro studies. For example, research has shown that compounds like isoliquiritigenin, found in licorice, can suppress the activity of the breast tissue-specific promoters I.3 and II.

This suggests a potential for dietary compounds to exert a more targeted effect, reducing local estrogen production Meaning ∞ Estrogen production describes the biochemical synthesis of estrogen hormones, primarily estradiol, estrone, and estriol, within the body. in peripheral tissues without drastically impacting systemic levels necessary for bone and brain health. This is a distinct advantage over pharmaceutical aromatase inhibitors, which systemically block the enzyme and can lead to side effects associated with profound estrogen deficiency.

However, the bioavailability and in-vivo potency of many of these dietary compounds are significantly lower than their pharmaceutical counterparts, making a diet rich in these substances a modulatory influence rather than a potent therapeutic blockade.

How Does Adipose Tissue Drive Estrogen Production?

Adipose tissue is a primary site of extragonadal estrogen synthesis, particularly in postmenopausal women and in men. This tissue expresses high levels of aromatase, converting circulating androgens into estrogens. The level of aromatase activity Meaning ∞ Aromatase activity defines the enzymatic process performed by the aromatase enzyme, CYP19A1. This enzyme is crucial for estrogen biosynthesis, converting androgenic precursors like testosterone and androstenedione into estradiol and estrone. in adipose tissue is not static; it is significantly influenced by the metabolic state of the individual. Obesity, and the associated state of chronic low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance, creates a powerful feed-forward cycle that drives estrogen production.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, which are overproduced in hypertrophied adipose tissue, have been shown to upregulate the CYP19A1 promoters that are active in fat cells. Concurrently, high levels of insulin, a hallmark of insulin resistance, also stimulate aromatase activity.

This creates a self-perpetuating loop ∞ excess adipose tissue increases inflammation and insulin resistance, which in turn increases aromatase activity within that same tissue, leading to higher local and systemic estrogen levels. This estrogen then promotes further fat storage, particularly in patterns conducive to metabolic disruption.

This powerful endocrine function of adipose tissue often represents the greatest challenge to managing estrogen conversion While direct aromatase-inhibiting peptides are not established, Gonadorelin supports natural testicular function, and growth hormone secretagogues improve metabolic health, indirectly aiding estrogen balance during TRT. through diet alone. While dietary changes can improve insulin sensitivity and reduce inflammation, in an individual with a significant burden of excess adiposity, the sheer volume of this endocrine-active tissue can overwhelm the more subtle modulatory effects of diet.

In the context of metabolic dysfunction, adipose tissue functions as a persistent, self-promoting factory for estrogen synthesis.

The Gut-Liver-Endocrine Axis a Systems Perspective

The ultimate bioavailability of estrogen is determined by a complex interplay between hepatic metabolism and gut microbial activity. The liver conjugates estrogens, primarily through glucuronidation and sulfation, to render them water-soluble for excretion. These conjugated estrogens are then transported to the gut via bile.

The gut microbiome, specifically the estrobolome, possesses a suite of enzymes, most notably beta-glucuronidase, that can deconjugate these estrogens. This deconjugation reverts them to their biologically active, lipid-soluble form, allowing for reabsorption into the enterohepatic circulation.

The composition and metabolic activity of the estrobolome Meaning ∞ The estrobolome refers to the collection of gut microbiota metabolizing estrogens. are profoundly shaped by diet. A diet high in diverse plant fibers and polyphenols supports a microbial community that maintains a healthy balance, favoring the excretion of estrogen. Conversely, a typical Western diet, low in fiber and high in processed fats and sugars, is associated with gut dysbiosis and higher beta-glucuronidase Meaning ∞ Beta-glucuronidase is an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of glucuronides, releasing unconjugated compounds such as steroid hormones, bilirubin, and various environmental toxins. activity.

This leads to increased estrogen reabsorption and a higher systemic estrogenic burden. Therefore, diet directly regulates the “leakiness” of the estrogen disposal system. An individual may have normal ovarian and adrenal estrogen production, but a dysbiotic gut can create a state of functional estrogen excess by constantly recycling what the liver has tried to eliminate.

In conclusion, dietary interventions are an indispensable tool for managing the systemic environment in which estrogen conversion and metabolism occur. They can modulate aromatase expression, reduce the inflammatory drive from adipose tissue, and optimize gut-mediated estrogen clearance. For many individuals with mild imbalances, these strategies may be sufficient to restore a healthy equilibrium.

However, in the presence of significant metabolic disease, high adiposity, or when using exogenous hormone therapies like TRT, diet alone is often insufficient to overcome the powerful biochemical drivers of estrogen production. In these clinical contexts, diet serves as a critical adjunctive therapy, creating a foundation of metabolic health upon which targeted pharmaceutical interventions can act more effectively and with fewer side effects.

The answer is one of synergy, where diet prepares the biological terrain and clinical protocols provide the precise, targeted action required for optimal outcomes.

References

- Balunas, Marcie J. and A. Douglas Kinghorn. “Natural products as aromatase inhibitors.” Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry, vol. 8, no. 6, 2008, pp. 646-82.

- Chen, Jian, et al. “Increased adipose tissue aromatase activity improves insulin sensitivity and reduces adipose tissue inflammation in male mice.” American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 308, no. 12, 2015, pp. E1146-57.

- Kwa, M. et al. “The Intestinal Microbiome and Estrogen Receptor ∞ Positive Female Breast Cancer.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 108, no. 8, 2016, djw029.

- Adlercreutz, H. and W. Mazur. “Phyto-oestrogens and Western diseases.” Annals of Medicine, vol. 29, no. 2, 1997, pp. 95-120.

- Williams, G. “Aromatase upregulation, insulin and raised intracellular oestrogens in men, induce adiposity, metabolic syndrome and prostate cancer, via aberrant ER-α and GPER signalling.” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, vol. 351, no. 2, 2012, pp. 269-78.

- Baker, Margaret E. “The estrobolome ∞ The gut microbiome and estrogen.” Journal of the Endocrine Society, vol. 3, no. Supplement_1, 2019, p. A504.

- Gibb, F. W. et al. “Higher Insulin Resistance and Adiposity in Postmenopausal Women With Breast Cancer Treated With Aromatase Inhibitors.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 104, no. 8, 2019, pp. 3479-86.

- Gruber, C. J. et al. “Production and actions of estrogens.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 346, no. 5, 2002, pp. 340-52.

- Vandromme, M. J. et al. “The effects of the gut microbiome on estrogen metabolism.” Journal of the Endocrine Society, vol. 5, no. Supplement_1, 2021, p. A963.

- Kalyani, R. R. et al. “Sex differences in the association of testosterone and estradiol with lipids and incident cardiovascular disease ∞ The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 99, no. 11, 2014, pp. 4146-55.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the biological terrain, detailing the pathways and mechanisms that govern your internal hormonal ecosystem. It illuminates the profound connection between what you consume and how your body functions on a microscopic level. This knowledge is a powerful first step, transforming abstract feelings of being unwell into an understandable, systems-based reality. It moves the conversation from one of passive suffering to one of active participation.

This understanding is the beginning of a new dialogue with your body. The path forward involves observing its responses, recognizing its signals, and making conscious choices that support its intricate balance. This journey is uniquely your own. The data and mechanisms are universal, but your individual response is personal.

Use this knowledge not as a rigid set of rules, but as a lens through which to view your own health. It is a tool to facilitate a more informed partnership with a clinical team who can help you integrate these foundational strategies with personalized protocols, ensuring that your path to wellness is both scientifically grounded and perfectly tailored to you.