Fundamentals

The experience of perimenopause is a profound biological shift, a recalibration of the body’s internal communication system. You may feel this as a constellation of symptoms ∞ changes in your cycle, shifts in mood, unpredictable hot flashes, or a subtle but persistent sense of being out of sync.

These are tangible signals from your body, reflecting a fundamental change in your hormonal architecture, primarily the fluctuating levels of estrogen. Your lived experience of these changes is the starting point for understanding the intricate biological processes at play. It is within this personal context that we can explore how a targeted nutritional intervention, specifically increasing dietary fiber, can become a foundational tool for restoring balance and reclaiming a sense of well-being.

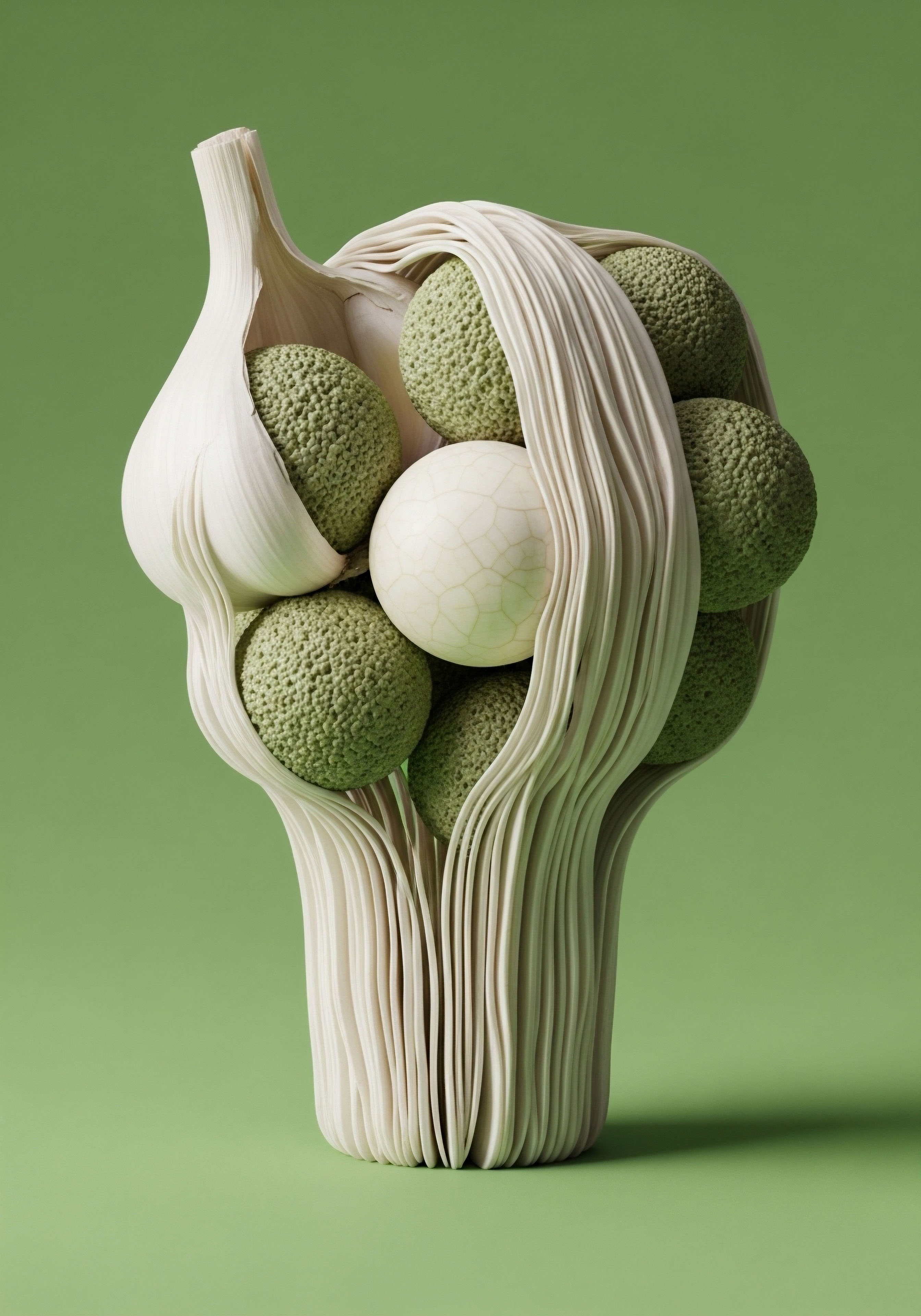

At its core, the connection between dietary fiber and hormonal balance lies within the gut. Think of your digestive system as a dynamic and intelligent ecosystem, a bustling metropolis of trillions of microorganisms known as the gut microbiome. This internal world does far more than simply process food; it actively participates in regulating your hormones.

When estrogen has completed its work in the body, it is sent to the liver to be packaged for removal. This “used” estrogen is then sent to the intestines for excretion. Here is where the gut microbiome enters the picture. A specific collection of gut bacteria, sometimes called the “estrobolome,” produces an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase.

This enzyme can unpack the used estrogen, allowing it to re-enter circulation. During perimenopause, when estrogen levels are already fluctuating unpredictably, an imbalanced gut microbiome can exacerbate the problem by reintroducing estrogen into the system at the wrong times, contributing to the very symptoms you are experiencing.

Dietary fiber acts as a master regulator within the gut, directly influencing how your body processes and eliminates estrogen.

This is where dietary fiber demonstrates its profound utility. Fiber acts as a powerful modulating force within this ecosystem. Soluble fiber, found in foods like oats, apples, and beans, dissolves in water to form a gel-like substance. This gel can bind to the packaged estrogen in the gut, preventing the beta-glucuronidase enzyme from setting it free.

This action ensures that excess estrogen is efficiently escorted out of the body through bowel movements, smoothing out the hormonal peaks and valleys that characterize perimenopause. Insoluble fiber, the “roughage” from sources like whole grains and vegetables, adds bulk to stool and promotes regularity.

This mechanical action reduces the time that used estrogen spends in the gut, further limiting the opportunity for it to be reactivated and reabsorbed. By supporting the body’s natural clearance pathways, a fiber-rich diet provides a direct, non-pharmacological strategy to help stabilize the hormonal environment.

This intervention extends beyond hormonal regulation. The metabolic shifts of perimenopause often include increased insulin resistance and changes in cholesterol levels, driven by the decline in estrogen’s protective effects. Dietary fiber powerfully counteracts these changes. It slows the absorption of sugar into the bloodstream, which helps to stabilize blood glucose and insulin levels, mitigating the risk of metabolic syndrome.

Soluble fiber is particularly effective at binding to cholesterol in the digestive tract and removing it from the body, supporting cardiovascular health at a time when it becomes a greater priority. Therefore, a focus on dietary fiber is a holistic strategy.

It addresses the root biochemical processes of estrogen imbalance while simultaneously providing robust support for the metabolic systems that are also in transition during this phase of life. This approach validates the interconnected nature of your symptoms and provides a clear, actionable path toward restoring systemic balance.

Intermediate

To fully appreciate how dietary fiber mitigates the symptoms of estrogen imbalance in perimenopause, we must examine the specific biochemical mechanisms at the interface of endocrinology and gastroenterology. The fluctuating hormonal milieu of perimenopause is defined by erratic estrogen production.

This can lead to periods of relative estrogen excess, where estrogen levels are high in relation to progesterone, contributing to symptoms like breast tenderness, heavy bleeding, and mood irritability. A targeted dietary fiber protocol directly intervenes in the enterohepatic circulation of estrogens, the continuous loop between the liver and the gut that determines the ultimate bioactivity of these hormones.

The Estrobolome and Its Modulation

The gut microbiome contains a functional subset of bacteria, the estrobolome, whose primary influence is on estrogen metabolism. The key enzymatic action here is that of bacterial beta-glucuronidase. After the liver conjugates (inactivates) estrogen by attaching a glucuronic acid molecule, it is excreted into the gut via bile.

High beta-glucuronidase activity in the gut cleaves this bond, deconjugating the estrogen and allowing it to be reabsorbed into the bloodstream in its active form. An unhealthy estrobolome, often characterized by low microbial diversity and an overgrowth of certain bacterial species, can lead to elevated beta-glucuronidase activity. This results in a greater burden of reactivated estrogen re-entering circulation, disrupting the delicate hormonal balance the body is trying to achieve during perimenopause.

Dietary fiber serves as the primary fuel source for a healthy, diverse microbiome. Different fibers selectively promote the growth of beneficial bacteria that create a less favorable environment for the high-beta-glucuronidase-producing species. For instance, soluble fibers are fermented by gut bacteria into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate.

These SCFAs have a systemically beneficial effect, including lowering the pH of the colon. This lower pH environment is less conducive to the activity of beta-glucuronidase, thereby reducing the amount of estrogen that gets reactivated. This creates a more favorable hormonal landscape, easing the burden of estrogen dominance symptoms.

How Do Different Fiber Types Contribute?

Soluble and insoluble fibers offer complementary mechanisms of action in hormonal regulation. Understanding their distinct roles allows for a more precise dietary strategy.

- Soluble Fiber ∞ Found in sources like psyllium husk, flax seeds, oats, barley, apples, and citrus fruits, this type of fiber forms a viscous gel in the digestive tract. This gel physically entraps conjugated estrogens, shielding them from bacterial enzymes and ensuring their passage out of the body. A clinical focus on increasing soluble fiber is a direct strategy to lower the circulating pool of active estrogens.

- Insoluble Fiber ∞ Present in whole grains, nuts, seeds, and the skins of many fruits and vegetables, this fiber does not dissolve in water. Instead, it increases fecal bulk and accelerates colonic transit time. This mechanical action is also critical; by speeding up the movement of waste through the intestines, it reduces the window of opportunity for bacterial beta-glucuronidase to act on conjugated estrogens.

A strategic combination of both soluble and insoluble fiber provides a multi-pronged approach to optimizing estrogen excretion and stabilizing hormonal fluctuations.

Metabolic Recalibration through Fiber

Perimenopause is a critical window for metabolic health. The relative decline in estrogen is associated with a decrease in insulin sensitivity and an unfavorable shift in lipid profiles, increasing the risk for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Dietary fiber interventions provide a powerful counterbalance to these metabolic derangements.

The table below outlines the dual benefits of fiber on both hormonal and metabolic health, illustrating the interconnectedness of these systems.

| System Affected | Mechanism of Fiber Action | Clinical Outcome in Perimenopause |

|---|---|---|

| Endocrine System (Hormonal Balance) | Binds to conjugated estrogens in the gut, inhibits beta-glucuronidase activity, and increases fecal excretion of estrogen. | Mitigation of symptoms related to estrogen excess, such as breast tenderness and heavy menstrual flow; smoother hormonal fluctuations. |

| Metabolic System (Glucose Control) | Slows gastric emptying and the absorption of glucose, leading to a more blunted postprandial glucose response. | Improved insulin sensitivity, reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes, and more stable energy levels. |

| Cardiovascular System (Lipid Profile) | Soluble fiber binds to bile acids (which are made from cholesterol) and excretes them, forcing the liver to pull more cholesterol from the blood to make new bile acids. | Lowering of LDL (“bad”) cholesterol and total cholesterol, reducing cardiovascular risk. |

By implementing a diet rich in a variety of fiber sources, an individual is not just addressing one symptom in isolation. They are supporting the entire physiological system as it navigates the complex transition of perimenopause. This integrated approach acknowledges that hormonal health and metabolic health are two sides of the same coin, and that a foundational intervention like dietary fiber can have profound and wide-reaching benefits.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of dietary fiber’s role in mitigating perimenopausal symptoms requires a deep dive into the molecular endocrinology of estrogen metabolism and its intersection with gut microbiology. The central thesis is that targeted fiber interventions can systematically alter the composition and enzymatic output of the estrobolome, thereby reducing the enterohepatic recirculation of estrogens and attenuating the high-amplitude fluctuations that drive symptomatology.

This perspective moves beyond simple binding and transit, focusing on the specific microbial shifts and metabolic consequences of fiber fermentation.

The Molecular Biology of Estrogen Deconjugation

Estrogens, primarily estradiol (E2) and estrone (E1), are rendered water-soluble for excretion in the liver through phase II conjugation, primarily via UDP-glucuronosyltransferases, forming estrogen-glucuronides. These conjugated forms are excreted in bile into the intestinal lumen.

The pivotal step in their potential reactivation is deconjugation by bacterial β-glucuronidase, an enzyme encoded by the gus gene found in various gut bacteria, notably in species within the Firmicutes phylum, such as certain Clostridium strains. High levels of β-glucuronidase activity effectively un-gate the conjugated estrogens, releasing them in their lipophilic, biologically active form for reabsorption across the intestinal mucosa and back into systemic circulation.

During perimenopause, the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis becomes less predictable. Anovulatory cycles can lead to periods of unopposed estrogen, while follicular hyperactivity can cause dramatic surges in estradiol. A highly active estrobolome compounds this intrinsic volatility. Research has shown that a diet low in fiber is often associated with lower microbial diversity and a higher abundance of β-glucuronidase-producing bacteria.

Conversely, diets rich in complex carbohydrates, including diverse fibers, promote a more diverse microbiome rich in saccharolytic bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

The fermentation of dietary fiber into short-chain fatty acids directly alters the gut environment to suppress the enzymatic activity responsible for estrogen reactivation.

SCFA-Mediated Regulation of the Estrobolome

The fermentation of prebiotic fibers (like inulin, fructooligosaccharides, and galactooligosaccharides) by commensal bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus yields high concentrations of SCFAs, particularly butyrate. Butyrate serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes, but its systemic effects are far-reaching. One critical function is the reduction of luminal pH.

The optimal pH for most bacterial β-glucuronidases is in the neutral to slightly alkaline range (pH 6.8-7.5). The acidic environment created by SCFA production (pH 5.5-6.5) significantly inhibits the efficacy of this enzyme, thus favoring the excretion of conjugated estrogens. This represents a direct biochemical mechanism through which fiber modulates hormonal balance.

The following table provides a detailed comparison of fiber types and their specific contributions to this regulatory process.

| Fiber Classification | Primary Mechanism of Action | Key Microbial Impact | Endocrinological Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soluble, Fermentable (e.g. Inulin, Pectin) | Undergoes rapid fermentation by colonic bacteria, producing high levels of SCFAs. | Promotes proliferation of beneficial genera like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus; lowers luminal pH. | Inhibition of β-glucuronidase activity, leading to reduced estrogen deconjugation and reabsorption. |

| Soluble, Viscous (e.g. Psyllium, Beta-glucans) | Forms a gel matrix that entraps bile acids and conjugated estrogens, physically impeding enzymatic access. | Less direct impact on microbial composition compared to fermentable fibers, but alters the substrate environment. | Increased fecal excretion of both cholesterol precursors and conjugated estrogens. |

| Insoluble (e.g. Cellulose, Lignin) | Increases fecal mass and reduces colonic transit time through its bulking effect. | Can positively influence microbial diversity by providing a scaffold for bacterial adhesion. | Decreases the duration of contact between conjugated estrogens and bacterial enzymes, reducing the overall probability of deconjugation. |

What Is the Impact on Systemic Inflammation?

The menopausal transition is often associated with a state of low-grade chronic inflammation, or “inflammaging.” This is driven in part by the loss of estrogen’s anti-inflammatory properties and can be exacerbated by metabolic dysfunction. The gut microbiome is a key regulator of systemic inflammation. A dysbiotic gut with increased intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”) allows for the translocation of bacterial components like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) into circulation, triggering a pro-inflammatory cascade via Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activation.

The SCFAs produced from fiber fermentation, particularly butyrate, are critical for maintaining intestinal barrier integrity. Butyrate enhances the expression of tight junction proteins (e.g. claudin, occludin), effectively sealing the gut lining. This reduces LPS translocation and lowers systemic inflammatory tone.

By mitigating this source of inflammation, a high-fiber diet can alleviate some of the more systemic symptoms of perimenopause, including joint pain, cognitive fog, and mood disturbances, which are often amplified by an inflammatory state. This demonstrates that the benefits of fiber extend well beyond direct estrogen modulation, addressing the broader physiological dysregulation that accompanies this life stage.

A clinical strategy, therefore, should not be a generic recommendation to “eat more fiber,” but a precision approach aimed at incorporating a diverse portfolio of fiber types. This ensures that all key mechanisms ∞ SCFA production, luminal pH reduction, physical binding, and transit time optimization ∞ are engaged. This multi-faceted intervention provides a robust, evidence-based foundation for managing the complex endocrinology of perimenopause.

References

- Zengul, A.G. et al. “Associations between Dietary Fiber, the Fecal Microbiota and Estrogen Metabolism in Postmenopausal Women with Breast Cancer.” Nutrition and Cancer, vol. 73, no. 7, 2021, pp. 1108-1117.

- “The Importance of Dietary Fibre during Menopause.” Jean Hailes for Women’s Health, 20 Apr. 2021.

- Várbíró, Szabolcs, et al. “The Importance of Nutrition in Menopause and Perimenopause ∞ A Review.” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 1, 2023, p. 147.

- Kwa, Mary, et al. “The Intestinal Microbiome and Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 108, no. 8, 2016.

- “Another Reason to Eat More Carbs ∞ Fiber.” Feisty Menopause, 10 May 2022.

- Reynolds, Andrew N. et al. “Dietary fibre and whole grains in diabetes management ∞ Systematic review and meta-analyses.” PLoS Medicine, vol. 17, no. 3, 2020, e1003053.

- Lepping, K. et al. “Dietary fiber intake and metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal African American women with obesity.” PLoS ONE, vol. 17, no. 9, 2022, e0273911.

- Baker, J. M. et al. “Estrogen-gut microbiome axis ∞ Physiological and clinical implications.” Maturitas, vol. 103, 2017, pp. 45-53.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Internal Ecosystem

The information presented here provides a biological roadmap, connecting the symptoms you feel to the systems that govern them. It illustrates that the body is not a collection of isolated parts but a deeply interconnected network. The conversation between your hormones and your gut microbiome is constant and profound.

Understanding this dialogue is the first step. The next is to recognize that you are not a passive observer of this process. The choices you make at every meal are direct inputs into this system. Introducing a diversity of fiber-rich foods is a deliberate act of recalibration, a way to send a clear signal to your body that you are supporting its transition.

This journey is one of self-study, of listening to the feedback your body provides as you modify your approach. The goal is to move from a place of reacting to symptoms to a position of proactively managing your unique physiology. This knowledge empowers you to become an active participant in your own wellness, armed with the understanding to build a foundation for long-term vitality.

Glossary

dietary fiber

hormonal balance

gut microbiome

beta-glucuronidase

estrobolome

soluble fiber

insoluble fiber

metabolic syndrome

enterohepatic circulation

estrogen metabolism

the estrobolome

into short-chain fatty acids

insulin sensitivity