Fundamentals

You may feel it as a persistent fatigue that coffee no longer fixes, or perhaps you see it in the mirror as a stubborn accumulation of weight around your midsection that resists diet and exercise. It could be the confusing signal of a blood pressure reading that has crept up over the years, or the energy crash that follows a meal.

These are not isolated frustrations; they are coherent messages from a biological system under strain. Your body is communicating a disruption in its metabolic processes, a state modern medicine has defined as metabolic syndrome. The question of whether a single dietary change, like increasing fiber, can correct this complex condition deserves a response that respects both your lived experience and the profound biological mechanisms at play.

The journey to understanding this connection begins by re-framing the conversation. We will look at dietary fiber as a primary tool for recalibrating your body’s internal communication network. The food you consume, particularly the types of fiber it contains, provides a set of instructions to the vast ecosystem residing in your gut.

This ecosystem, in turn, sends critical signals to the rest of your body, influencing everything from how you store fat to how your cells respond to insulin. Therefore, a deliberate increase in fiber intake is a direct intervention into this signaling cascade, an opportunity to rewrite the metabolic messages being sent throughout your system.

Understanding Metabolic Syndrome as a Systemic Signal

Metabolic syndrome is a collection of five specific metabolic markers that, when present together, indicate a significantly higher risk for developing cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Think of these markers as five distinct warning lights on your body’s dashboard. The presence of three or more of these signals confirms a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome, indicating that the core machinery of your metabolism is functioning inefficiently.

These markers are:

- Abdominal Obesity A large waistline is a physical sign that fat is being stored viscerally, around your internal organs. This type of fat is metabolically active and disruptive, releasing inflammatory signals that interfere with normal hormonal function.

- Elevated Triglycerides High levels of these fats in your blood indicate that your body is not efficiently clearing lipids from your circulation, often due to an over-consumption of refined carbohydrates and sugars.

- Low High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL) Cholesterol Low levels of this “good” cholesterol mean your body has a reduced capacity to remove harmful cholesterol from your arteries, a process vital for cardiovascular health.

- High Blood Pressure Consistently elevated blood pressure, or hypertension, signifies that your cardiovascular system is under continuous strain, which can damage blood vessels over time.

- Elevated Fasting Blood Glucose High blood sugar levels after a period of fasting are a primary indicator of insulin resistance, a state where your body’s cells are no longer responding properly to the hormone insulin.

A diagnosis of metabolic syndrome is a clear indication that the body’s systems for processing energy and regulating inflammation are becoming overwhelmed.

Viewing these five markers together provides a holistic picture. They tell a story of systemic dysfunction where the body’s ability to manage energy is compromised. The core of this dysfunction often lies in insulin resistance, a condition where the intricate hormonal dance that governs blood sugar becomes desynchronized, leading to a cascade of metabolic consequences that manifest as these five distinct signals.

Dietary Fiber the Master Regulator

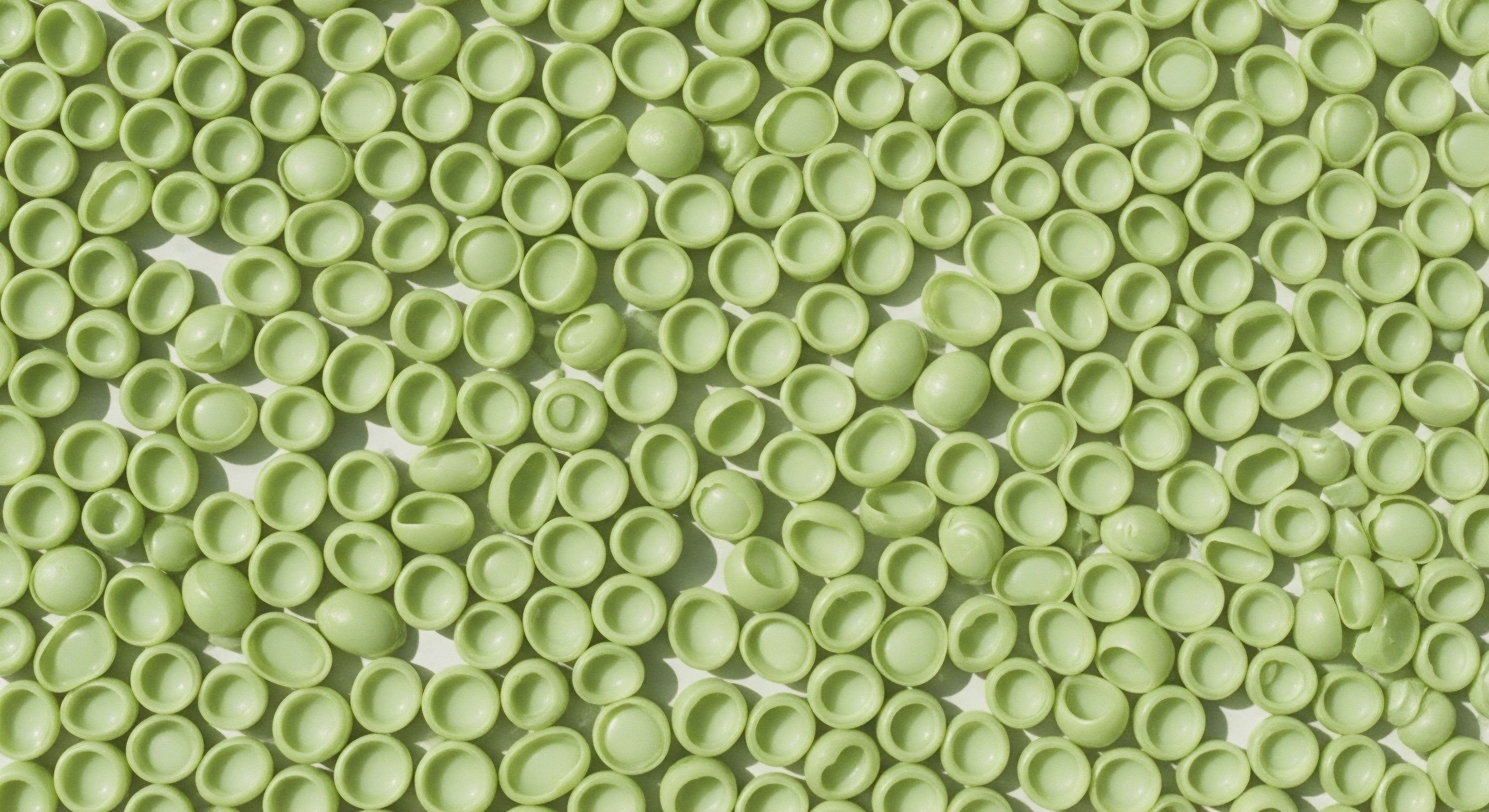

Dietary fiber is a class of complex carbohydrates found in plant-based foods like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes. Unlike other carbohydrates, fiber passes through the small intestine largely undigested. Its journey concludes in the large intestine, where it becomes a crucial resource for the trillions of microorganisms that constitute your gut microbiome. Fiber is broadly categorized into two main types, each with a distinct role in your physiology.

Soluble Fiber This type of fiber dissolves in water to form a viscous, gel-like substance in the digestive tract. You can find it in foods like oats, barley, apples, citrus fruits, and beans. Its primary function is to slow down digestion. This action has a profound stabilizing effect on blood sugar levels by moderating the absorption of glucose into the bloodstream. It also plays a key role in binding to bile acids, which helps lower cholesterol.

Insoluble Fiber This fiber does not dissolve in water. It adds bulk to the stool and acts like a broom, sweeping through the digestive system to promote regularity and prevent constipation. It is abundant in whole grains, nuts, seeds, and vegetables like cauliflower and green beans. While its direct impact on cholesterol or blood sugar is less pronounced than that of soluble fiber, its role in maintaining a healthy and efficient digestive tract is foundational to overall wellness.

The decision to increase dietary fiber intake is a strategic choice to supply your body with the raw materials it needs to restore metabolic order. By providing these specific types of carbohydrates, you are directly influencing the pace of digestion, the absorption of nutrients, and, most importantly, the health and activity of your gut microbiome, which is the central theme of our deeper exploration.

Intermediate

Having established that metabolic syndrome is a systemic communication breakdown and that fiber is a key signaling molecule, we can now examine the precise mechanisms through which this communication occurs. The journey of dietary fiber through your digestive system is where its therapeutic potential is unlocked.

When soluble fiber reaches the large intestine, it becomes the primary fuel for a vast and complex fermentation process carried out by your gut microbiota. This process generates a host of bioactive compounds that enter your circulation and orchestrate widespread metabolic and hormonal effects. Understanding this translation from inert plant material to potent biological messenger is key to appreciating how fiber can so profoundly influence your health.

The Gut Microbiome as a Metabolic Bioreactor

Your large intestine houses a dense and diverse community of bacteria, fungi, and other microbes. This ecosystem functions as a sophisticated bioreactor, breaking down compounds that your own digestive enzymes cannot. When you consume soluble fiber, you are feeding the beneficial bacteria within this community. These microbes ferment the fiber, transforming it into a range of metabolites, the most important of which are short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

The three primary SCFAs produced are:

- Butyrate This is the preferred energy source for the cells lining your colon (colonocytes). A steady supply of butyrate keeps the gut barrier strong and intact, preventing inflammatory molecules from leaking into the bloodstream.

- Propionate This SCFA is primarily transported to the liver, where it plays a direct role in regulating the production of glucose and cholesterol. It helps to reduce the liver’s output of new glucose, a critical function for improving insulin sensitivity.

- Acetate As the most abundant SCFA, acetate enters the peripheral circulation and travels throughout the body. It can cross the blood-brain barrier to influence appetite signals and is used by various tissues as a substrate for energy and fat synthesis.

The production of short-chain fatty acids from fiber fermentation is the central mechanism linking gut health to systemic metabolic regulation.

The amount and type of SCFAs produced depend entirely on the types of fiber you consume and the composition of your unique microbiome. A diet rich in diverse plant fibers cultivates a robust and varied microbial community capable of producing a balanced profile of these beneficial compounds.

How Do SCFAs Directly Improve Metabolic Markers?

The SCFAs generated in your gut do not remain there. They are absorbed into your system and act as powerful signaling molecules, directly addressing the five markers of metabolic syndrome through a variety of pathways. This is where fiber’s role transitions from simple digestion to active metabolic therapy.

One of the most significant actions of SCFAs is their ability to stimulate the release of key gut hormones. By binding to specific receptors on intestinal endocrine cells (L-cells), butyrate and propionate trigger the secretion of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) and Peptide YY (PYY). These hormones are central players in metabolic regulation.

GLP-1 is a powerful hormone that enhances insulin secretion from the pancreas in response to glucose, improves the body’s overall sensitivity to insulin, slows down gastric emptying (which keeps you feeling full), and signals satiety to the brain. Many modern injectable medications for diabetes and weight loss are synthetic versions of this very hormone, highlighting its therapeutic importance. Increasing fiber intake is a natural way to boost your own production of GLP-1.

PYY works in concert with GLP-1 to suppress appetite. It is released after meals and acts on the hypothalamus in the brain to reduce hunger, helping to control caloric intake and promote weight management.

The table below outlines how different types of fiber and their resulting actions map onto the specific markers of metabolic syndrome.

| Metabolic Marker | Primary Mechanism of Fiber Action | Key Fiber Type |

|---|---|---|

| Elevated Fasting Glucose |

Slowed glucose absorption due to gel formation; enhanced insulin sensitivity via GLP-1 secretion. |

Soluble (Oats, Psyllium) |

| Abdominal Obesity |

Increased satiety and reduced appetite via GLP-1 and PYY; delayed gastric emptying. |

Soluble (Beans, Apples) |

| Elevated Triglycerides |

Binding to bile acids, forcing the liver to use cholesterol to make more, thereby lowering circulating lipids. |

Soluble (Barley, Brussels Sprouts) |

| Low HDL Cholesterol |

Indirect improvements as overall metabolic health and lipid metabolism are restored. |

Mixed Sources |

| High Blood Pressure |

SCFAs may influence vascular function and sodium handling; weight loss reduces overall cardiovascular strain. |

Mixed Sources |

This demonstrates that fiber’s benefits are not the result of a single action but a cascade of integrated physiological events. The physical properties of fiber in the gut, combined with the biochemical power of the SCFAs produced during fermentation, create a multi-pronged therapeutic effect that addresses the root causes of metabolic dysfunction.

Academic

To fully address the question of whether dietary fiber intake alone can significantly improve metabolic syndrome, we must move beyond its established effects on gut hormones and digestion and into the more nuanced realms of cellular biology, epigenetics, and the body’s master hormonal control systems.

The answer lies in understanding the limits of fiber’s influence and recognizing the powerful hormonal and inflammatory headwinds that can overwhelm its benefits. While fiber is a potent tool, its efficacy is contingent upon the broader biological context of the individual, including their existing hormonal status and the inflammatory tone of their body.

Butyrate as an Epigenetic Regulator a Deeper Mechanism

The short-chain fatty acid butyrate possesses a profound biological activity that extends far beyond its role as a fuel source for colonocytes. Butyrate is a potent histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor. To understand the significance of this, we must first understand the basics of epigenetics.

Your DNA contains the blueprint for every protein your body can make, but epigenetics is the system of chemical tags that tells your genes when to turn on or off. Histone deacetylases are enzymes that typically remove “acetyl” tags from histones, which are the proteins that DNA is wound around. This removal causes the DNA to coil more tightly, making the genes in that region inaccessible and effectively silencing them.

By inhibiting HDACs, butyrate prevents the removal of these acetyl tags. This keeps the DNA more loosely wound, allowing for the transcription of genes that are often suppressed in states of chronic inflammation and metabolic disease. This epigenetic mechanism means that a metabolite produced by your gut bacteria from the fiber you eat can directly influence the genetic expression in your cells. Specifically, HDAC inhibition by butyrate has been shown to:

- Suppress Inflammatory Pathways It can reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-alpha and IL-6, which are key drivers of insulin resistance.

- Enhance Oxidative Stress Resistance It can upregulate the expression of genes involved in cellular antioxidant defenses.

- Promote Gut Barrier Integrity It strengthens the tight junctions between intestinal cells by modulating the expression of the proteins that form them.

This epigenetic activity is a primary reason why fiber’s impact can be so systemic. It provides a direct mechanistic link between diet, the gut microbiome, and the regulation of inflammation at the genetic level.

What Is Fibers Role in the HPA Axis?

Metabolic syndrome does not develop in a vacuum. It is deeply intertwined with the body’s central stress response system, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. Chronic stress, whether psychological or physiological, leads to sustained activation of the HPA axis and elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

Persistently high cortisol is a powerful driver of metabolic dysfunction; it promotes the breakdown of muscle tissue, increases glucose production in the liver, and directly contributes to insulin resistance and the accumulation of visceral adipose tissue.

Here, the health of the gut microbiome, modulated by fiber intake, becomes critically important. A dysbiotic gut, characterized by low microbial diversity and an overgrowth of inflammatory bacteria, can lead to increased intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”). This allows bacterial components like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to enter the bloodstream, triggering a low-grade systemic inflammatory response.

This inflammation is a potent activator of the HPA axis. Conversely, a healthy microbiome, nourished by a high-fiber diet and producing ample butyrate, strengthens the gut barrier and reduces this inflammatory signaling, thereby helping to downregulate HPA axis activity and buffer the body from the metabolic consequences of chronic stress.

Fiber’s ability to modulate the HPA axis via the gut-brain connection is a critical, often overlooked, component of its therapeutic effect on metabolic health.

Limitations Why Fiber Alone May Be Insufficient

Despite these powerful mechanisms, fiber intake alone may not be enough to reverse metabolic syndrome in all individuals. Its efficacy is modulated by several factors that can limit its potential.

| Limiting Factor | Biological Rationale | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Microbiome Composition |

The therapeutic effects of fiber are dependent on the presence of specific bacteria capable of fermenting it into beneficial SCFAs. An individual with a severely depleted or dysbiotic microbiome may lack the necessary microbial machinery. |

Benefit may be limited until the microbiome is restored through other means (e.g. probiotics, fermented foods) in addition to fiber. |

| Hormonal Status (HPG Axis) |

In conditions like menopause or andropause, the decline in estrogen and testosterone (the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal axis) is a primary driver of insulin resistance and visceral fat gain. These hormonal shifts can create a metabolic headwind that fiber alone cannot overcome. |

Hormonal optimization protocols (e.g. TRT) may be necessary to restore metabolic balance, with fiber acting as a crucial supportive therapy. |

| Severity of Insulin Resistance |

In individuals with advanced type 2 diabetes or severe insulin resistance, the cellular machinery for responding to insulin is already significantly impaired. While fiber can improve sensitivity, it may not be sufficient to restore normal function without pharmacological or other lifestyle interventions. |

Fiber is a foundational element of management, but may need to be combined with medical treatment and significant carbohydrate restriction. |

| Genetic Predisposition |

Genetic factors can influence an individual’s susceptibility to insulin resistance, lipid disorders, and hypertension, setting a higher baseline of metabolic dysfunction. |

A higher fiber intake is beneficial, but may not fully normalize metabolic markers in the face of strong genetic risk. |

Therefore, a clinically sophisticated perspective views dietary fiber as a foundational and indispensable pillar of metabolic health. It directly addresses gut health, inflammation, and key hormonal signaling pathways. For individuals with early-stage metabolic dysfunction, a significant increase in fiber intake from diverse sources can indeed produce dramatic improvements and may even be sufficient for reversal.

However, for those with more advanced disease or significant underlying hormonal dysregulation, fiber becomes a critical adjunctive therapy. It creates a biological environment in which other interventions, from exercise to medication to hormone therapy, can be more effective. It is the essential groundwork upon which a resilient metabolic system is built.

References

- Weickert, Martin O. and Andreas F. H. Pfeiffer. “Metabolic Effects of Dietary Fiber Consumption and Prevention of Diabetes.” The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 138, no. 3, 2008, pp. 439-442.

- Barber, Thomas M. et al. “The Health Benefits of Dietary Fibre.” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 10, 2020, p. 3209.

- Canfora, Ellen E. et al. “Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Control of Body Weight and Insulin Sensitivity.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology, vol. 11, no. 10, 2015, pp. 577-591.

- Sivaprakasam, Senthir, et al. “Benefits of Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Their Receptors in Gut and Other Tissues.” Annual Review of Physiology, vol. 78, 2016, pp. 1-29.

- Chang, Pao-Yang, et al. “The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 111, no. 6, 2014, pp. 2247-2252.

- Hewitt, C. S. et al. “The HDAC Inhibitor Butyrate Impairs β Cell Function and Activates the Disallowed Gene Hexokinase I.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 22, no. 24, 2021, p. 13330.

- Anagnostis, P. et al. “New Insights into the Role of Insulin and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis in the Metabolic Syndrome.” Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, vol. 24, no. 2, 2023, pp. 243-255.

- Jones, K. L. et al. “Stress, the HPA Axis, and the HPG Axis ∞ A Role for Glucocorticoids in the Regulation of the Menstrual Cycle.” Endocrinology, vol. 156, no. 8, 2015, pp. 2686-2695.

- Ye, Jian. “Mechanisms of Glucocorticoid-Induced Insulin Resistance.” Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 219, no. 1, 2013, R1-R11.

- McRae, M. P. “Dietary Fiber is Beneficial for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease ∞ An Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses.” Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, vol. 16, no. 4, 2017, pp. 289-299.

Reflection

Listening to Your Body’s Conversation

The information presented here offers a biological blueprint, translating the abstract concept of “eating more fiber” into a detailed account of cellular and hormonal communication. The science is clear ∞ the fibers you consume initiate a cascade of events that can fundamentally alter your metabolic trajectory.

Yet, knowledge is only the first part of the equation. The true process of reclaiming your vitality begins when you start to apply this understanding as a lens through which to view your own body and its unique signals.

Consider the daily fluctuations in your energy, your appetite, and your mood. These are not random occurrences. They are data points in a continuous conversation between your diet, your microbiome, and your hormonal systems. By deliberately modifying one of the key inputs to this system ∞ your fiber intake ∞ you are actively participating in that conversation. You are providing your body with a new set of instructions and creating the potential for a different outcome.

This path is one of self-awareness and partnership with your own physiology. The ultimate goal is to move from a state of being a passive recipient of symptoms to becoming an active architect of your own wellness. The journey to resolving metabolic dysfunction is deeply personal, and while the principles are universal, the application is unique to you. The knowledge you have gained is the tool; your proactive engagement is the catalyst for change.

Glossary

blood pressure

metabolic syndrome

dietary fiber

fiber intake

insulin resistance

blood sugar

gut microbiome

soluble fiber

insoluble fiber

short-chain fatty acids

butyrate

insulin sensitivity

glp-1

metabolic health

metabolic dysfunction

histone deacetylase