Fundamentals

You have begun a protocol of biochemical recalibration, a precise and personalized regimen designed to restore your body’s hormonal equilibrium. The weekly cadence of injections, the carefully timed ancillary medications ∞ these are the powerful, externally supplied inputs.

Yet, you may be sensing that the full expression of your renewed vitality is also shaped by the daily, seemingly mundane choices you make. One of the most fundamental of these is what you place on your fork.

The question of whether dietary fiber, the humble and often overlooked component of our food, can influence the outcomes of your testosterone replacement therapy is a profound one. It speaks to a deeper truth of human physiology ∞ the body is an interconnected system, where the gut, the endocrine system, and the brain are in constant communication.

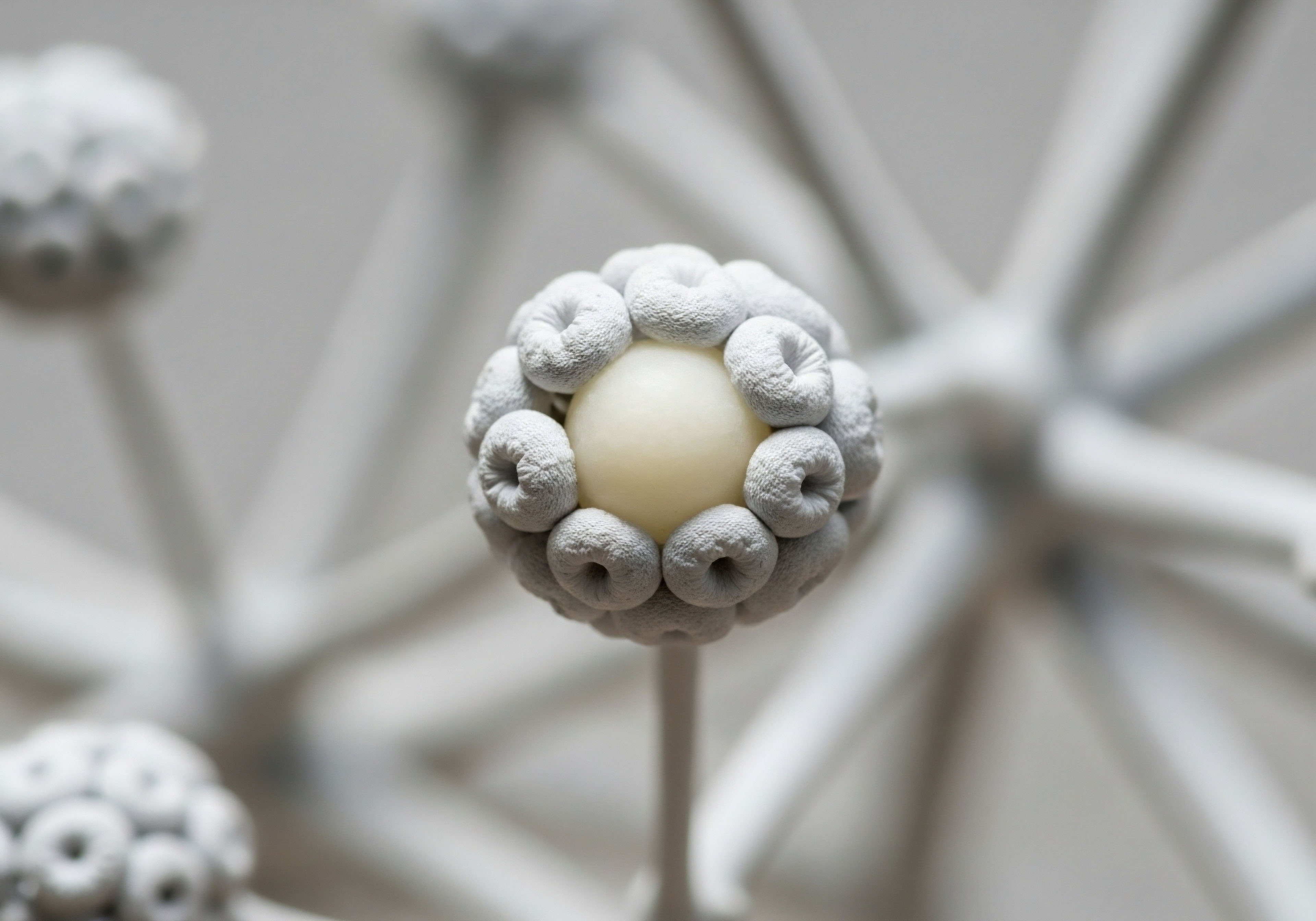

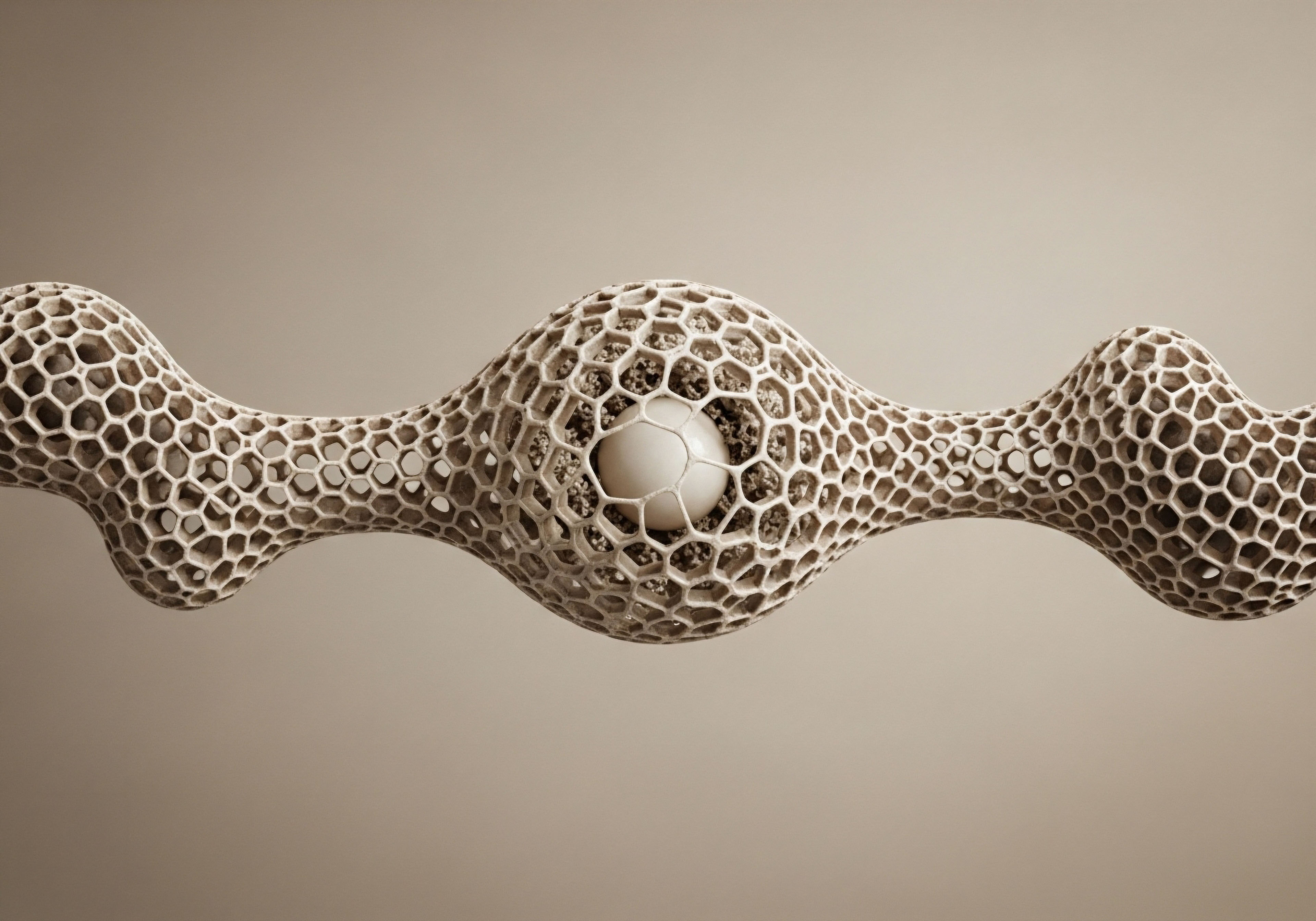

To understand this connection, we must first appreciate what dietary fiber is from a biological standpoint. It is a category of complex carbohydrates that human digestive enzymes cannot break down. Fiber travels through the small intestine largely intact, arriving in the colon, where it becomes the primary sustenance for the trillions of microorganisms that reside there.

This vast community of bacteria, fungi, and other microbes is collectively known as the gut microbiome. This internal ecosystem functions as a dynamic and responsive metabolic organ, one that plays a direct role in regulating your health.

The Two Faces of Fiber

Dietary fiber is broadly classified into two main types based on its interaction with water, and each type has distinct physiological effects.

- Soluble Fiber This type dissolves in water to form a gel-like substance in the digestive tract. It is found in foods like oats, barley, nuts, seeds, beans, lentils, and some fruits and vegetables. Its primary role is to slow down digestion, which can help with blood sugar control and creates a sense of fullness. More importantly, it is highly fermentable by the gut microbiota.

- Insoluble Fiber This type does not dissolve in water. It adds bulk to the stool and can help food pass more quickly through the stomach and intestines. It is found in foods like whole grains, nuts, and vegetables such as cauliflower, green beans, and potatoes. It acts as a “bulking agent,” promoting regular bowel movements.

The relevance of these fiber types to your hormonal health protocol lies in their downstream effects. When soluble fiber is fermented by your gut bacteria, they produce powerful metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, propionate, and acetate. These molecules are absorbed into your bloodstream and act as signaling agents, influencing everything from inflammation to liver function.

Hormone Transport and the Role of SHBG

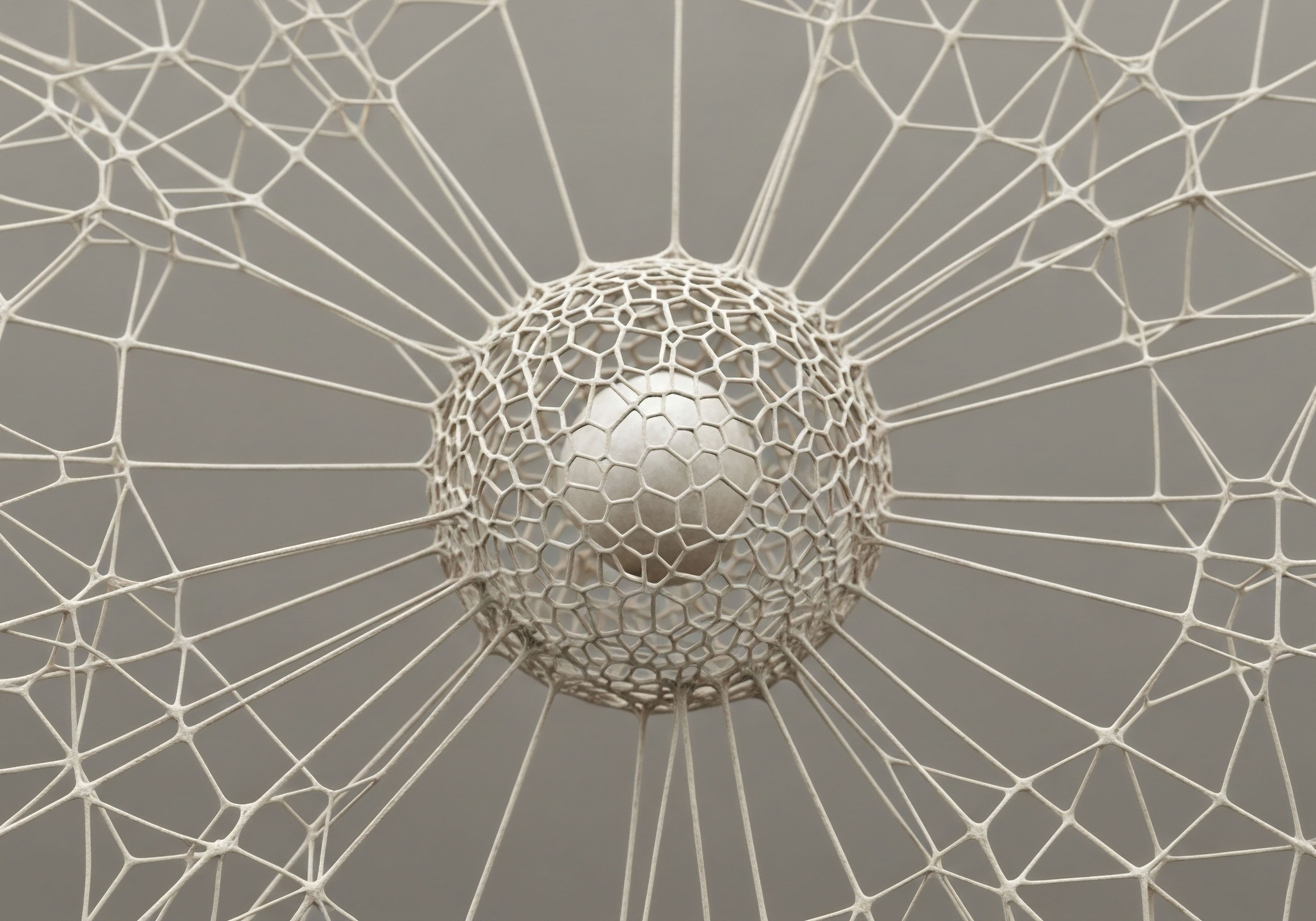

Testosterone, whether produced naturally by your body or administered therapeutically, does not simply float freely in your bloodstream. A significant portion of it is bound to proteins. The most important of these is Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG). You can think of SHBG as a transport vehicle and a storage unit for sex hormones.

When testosterone is bound to SHBG, it is inactive and unavailable to be used by your cells. Only the “free” or unbound portion of testosterone can enter cells and exert its biological effects. Therefore, the amount of SHBG in your blood is a critical determinant of how much active testosterone your body can actually use.

The gut microbiome functions as a metabolic organ, and the fiber you consume is the primary fuel that determines its health and activity.

Dietary choices, particularly fiber intake, can influence the liver’s production of SHBG. A higher fiber intake has been associated in some clinical contexts with an increase in SHBG levels. For an individual on a hormonal optimization protocol, understanding and managing SHBG levels is a central part of achieving the desired clinical outcome.

An elevated SHBG can mean that even with adequate total testosterone levels, you may not be experiencing the full benefits because a smaller portion of it is free and active.

Enterohepatic Circulation the Body’s Recycling System

Your body has a sophisticated process for conserving and eliminating substances called enterohepatic circulation. Hormones, after being used by the body, are sent to the liver to be metabolized. The liver conjugates them, packaging them into a water-soluble form that can be excreted in bile.

This bile is released into the small intestine to aid in digestion. Here, some of the hormones can be deconjugated by gut bacteria and reabsorbed back into the bloodstream, re-entering circulation. This recycling pathway has a significant impact on the body’s total hormone load.

Dietary fiber directly interrupts this process. By binding to bile acids and conjugated hormones in the gut, fiber prevents their reabsorption. It effectively traps them and ensures they are excreted from the body in the stool. This mechanism is particularly relevant for estrogen metabolism.

By increasing the fecal excretion of estrogens, a high-fiber diet can lower the overall estrogen load in the body. For a man on TRT who is also taking an aromatase inhibitor to control the conversion of testosterone to estrogen, this dietary influence can be a powerful complementary strategy. It helps to clear estrogen from the system, potentially reducing the burden on the ancillary medication and contributing to a more favorable testosterone-to-estrogen ratio.

Intermediate

For the individual engaged in a hormonal optimization protocol, the foundational knowledge of fiber’s role sets the stage for a more detailed clinical inquiry. The central question becomes ∞ how do these mechanisms translate into tangible effects on my therapy?

The answer lies in examining the interplay between dietary fiber, the gut microbiome, and the specific pharmacological agents used in Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT). The goal of a well-managed protocol is to establish a stable and predictable hormonal environment. Understanding how your diet can either support or disrupt this stability is paramount.

How Does Fiber Directly Influence Hormone Lab Markers?

Clinical studies have provided data on the relationship between diet composition and key hormonal parameters. While much of the research has focused on natural hormone production, the physiological principles are directly applicable to a person on TRT. The primary confounder in many studies is the inverse relationship between fat and fiber content in test diets. Diets high in fiber are often correspondingly lower in dietary fat.

A controlled feeding study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition provided significant insight. Men who consumed a high-fat, low-fiber diet showed higher concentrations of total and SHBG-bound testosterone compared to when they consumed a low-fat, high-fiber diet.

This suggests that a lower fiber intake, in the context of higher fat consumption, may lead to lower SHBG levels. For a TRT patient, lower SHBG can mean higher free testosterone, which is often the therapeutic target.

Conversely, a very high-fiber, low-fat diet could potentially increase SHBG, binding up more of the administered testosterone and reducing its effectiveness at the cellular level. This demonstrates that your dietary pattern is an active variable in your treatment, one that can modulate the very markers your clinician is tracking.

| Dietary Protocol | Impact on Total Testosterone | Impact on SHBG-Bound Testosterone | Impact on Urinary Estrogen Excretion |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Fat, Low-Fiber |

Increased |

Increased |

Decreased |

| Low-Fat, High-Fiber |

Decreased |

Decreased |

Increased |

This data underscores the importance of a balanced approach. A diet excessively high in fiber and low in healthy fats might work against the goals of TRT by elevating SHBG. A diet devoid of fiber, on the other hand, would neglect the critical role of the gut microbiome in overall metabolic health and estrogen clearance. The optimal strategy involves consuming sufficient fiber to support gut health and estrogen metabolism without excessively elevating SHBG.

The Microbiome Aromatase and Estrogen Management

The conversion of testosterone to estradiol, a potent estrogen, is mediated by the aromatase enzyme. This process occurs in various tissues, including fat cells, the brain, and bone. Managing this conversion is a cornerstone of successful TRT for many men, which is why an aromatase inhibitor (AI) like Anastrozole is often included in the protocol. Anastrozole works by blocking the aromatase enzyme, thereby reducing the amount of testosterone that gets converted into estrogen.

Your dietary pattern is an active variable in your therapy, capable of modulating the very hormonal markers your clinician tracks to gauge success.

The gut microbiome adds another layer of control over estrogen levels. An imbalanced microbiome, or “dysbiosis,” can lead to a state of low-grade systemic inflammation. This inflammation can, in turn, increase aromatase activity throughout the body, leading to higher estrogen levels. This means that a poorly managed gut could be working against the action of your prescribed Anastrozole, forcing you to rely more heavily on the medication to keep estrogen in check.

This is where specific types of fiber become clinically relevant. These fibers act as prebiotics, promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria that produce anti-inflammatory short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). By improving gut health and reducing systemic inflammation, a strategic fiber intake can help to naturally down-regulate aromatase expression. This creates a synergistic effect with your AI, allowing for more stable and effective estrogen management.

Clinically Relevant Fiber Types

- Inulin and Fructooligosaccharides (FOS) Found in foods like chicory root, Jerusalem artichokes, onions, and garlic, these fibers are potent prebiotics that fuel the growth of Bifidobacteria, a key beneficial genus in the gut.

- Beta-Glucans Present in oats and barley, these soluble fibers are known for their ability to lower cholesterol and improve glycemic control, both of which are important for metabolic health and can indirectly support a healthy hormonal profile.

- Resistant Starch Found in cooked and cooled potatoes, green bananas, and legumes, this type of starch “resists” digestion and ferments in the colon, leading to significant butyrate production. Butyrate is the primary fuel for the cells lining the colon and has powerful anti-inflammatory effects.

What about the Absorption of Ancillary Medications?

Most TRT protocols involve injectable testosterone, so fiber’s impact on its direct absorption is minimal. However, ancillary medications like Anastrozole, Tamoxifen, or Clomiphene are administered orally. Dietary fiber, particularly the soluble, gel-forming type, can slow down gastric emptying and has the potential to bind to drugs within the digestive tract.

This can alter the pharmacokinetics of a medication, potentially reducing its peak concentration or slowing its absorption rate. While this effect is generally modest for most drugs, it is a factor to consider. For maximal consistency, it is a sound clinical practice to take oral medications separately from very high-fiber meals or fiber supplements. This ensures that the absorption of these critical ancillary drugs is as predictable and consistent as the injectable components of your therapy.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the relationship between dietary fiber and testosterone replacement therapy demands a systems-biology perspective. We must move beyond simple correlations and examine the intricate molecular pathways that connect the gut lumen to the endocrine system. The modern TRT protocol is a form of applied endocrinology, designed to restore a physiological state.

The patient’s diet, and specifically their fiber intake, is a powerful environmental input that constantly modulates the very biological terrain this therapy seeks to optimize. The interaction is not a simple one-to-one relationship; it is a complex network of signaling loops involving the gut, the liver, and cellular receptor sites.

The Gut-Liver-Hormone Axis and the Estrobolome

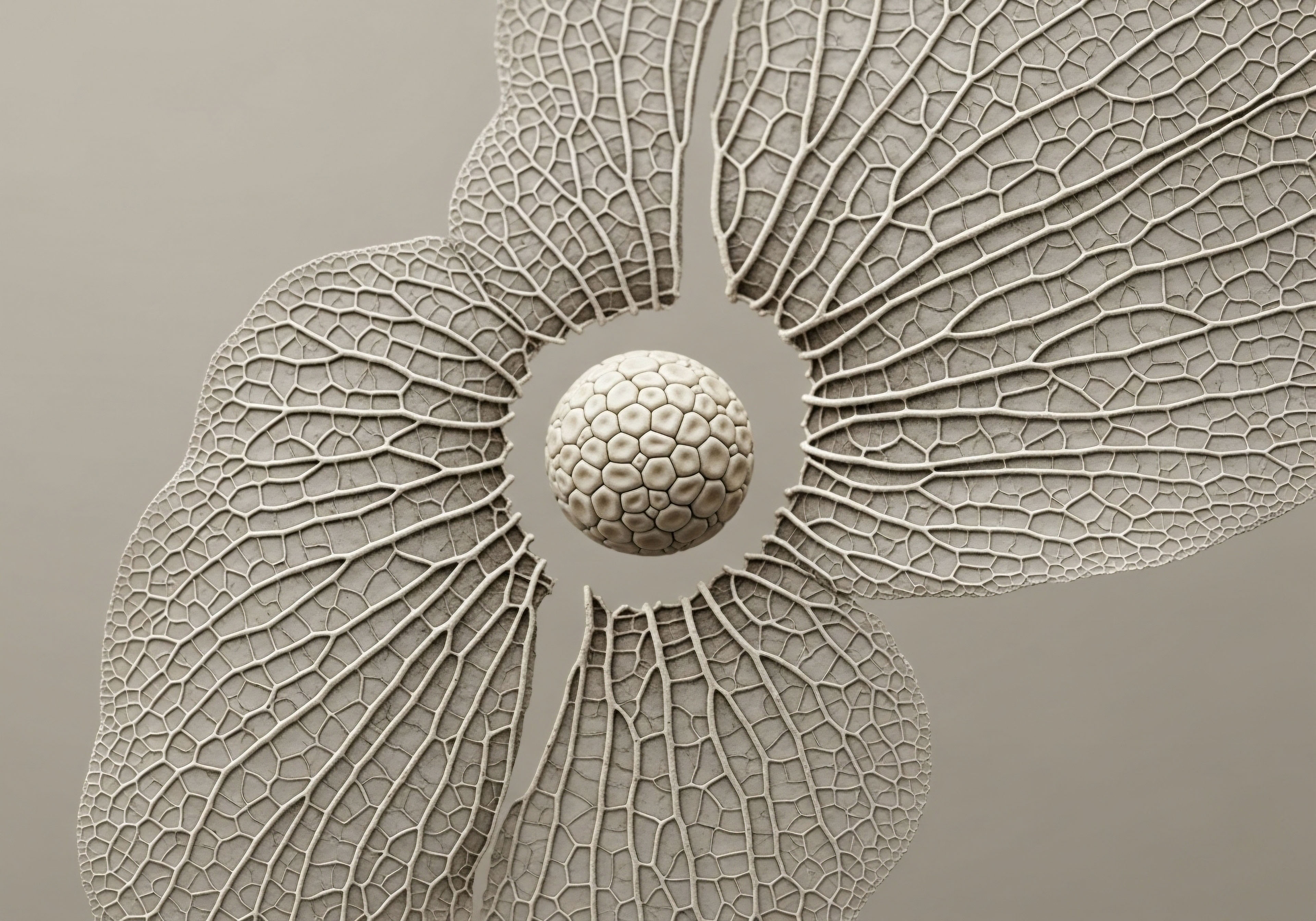

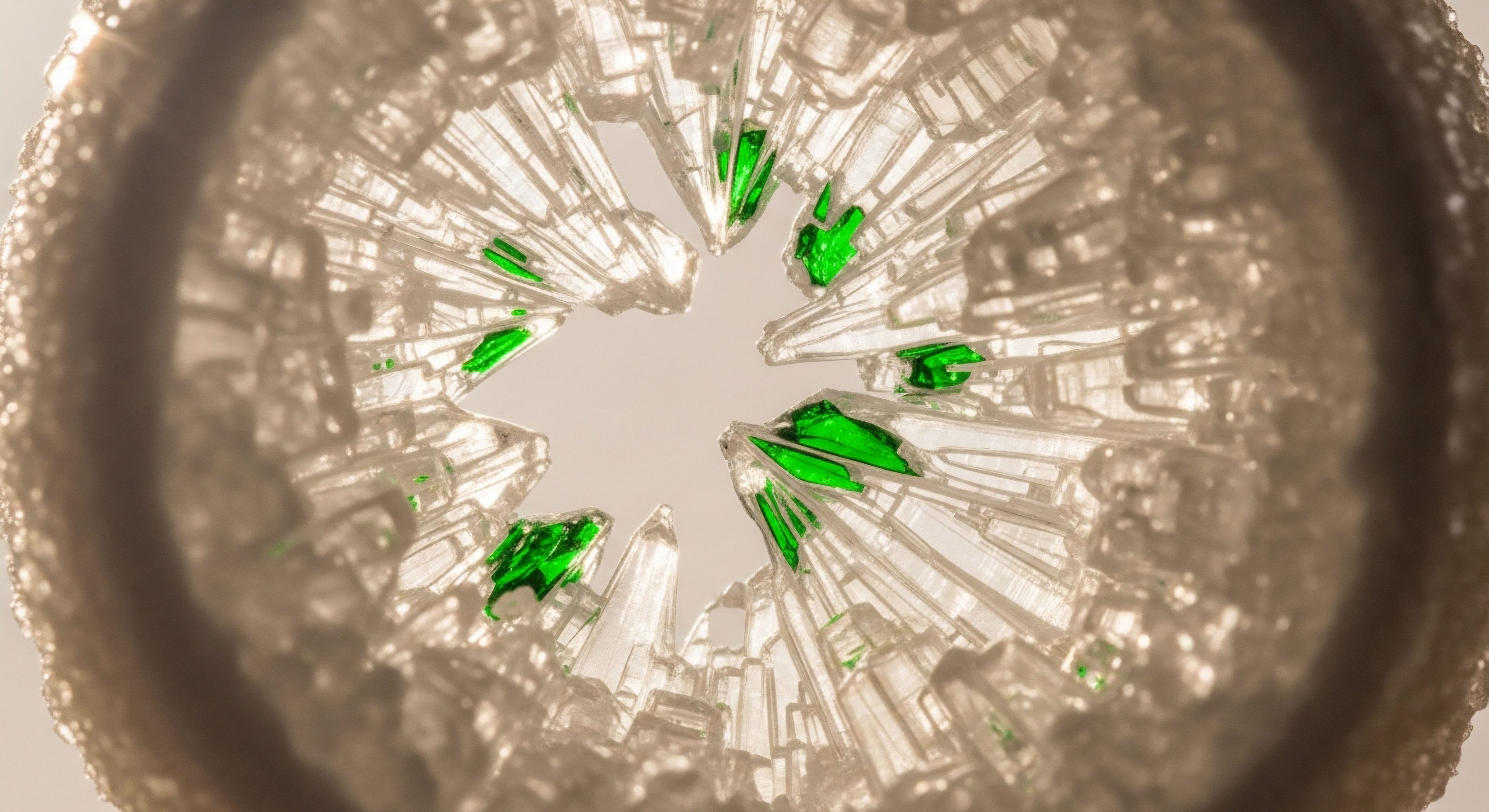

The concept of the “estrobolome” is central to this discussion. The estrobolome is defined as the aggregate of enteric bacterial genes whose products are capable of metabolizing estrogens. After the liver conjugates estrogens into forms destined for excretion (e.g. estradiol-glucuronide), they are secreted into the gut via bile.

Here, certain bacteria in the estrobolome produce enzymes, most notably β-glucuronidase, which can deconjugate these estrogens. This action liberates the free estrogen, allowing it to be reabsorbed into the bloodstream through the enterohepatic circulation. The activity level of the estrobolome, therefore, functions as a regulator of systemic estrogen levels.

Dietary fiber is the primary modulator of the estrobolome’s composition and metabolic activity. A diet rich in diverse plant fibers promotes a healthy, diverse microbiome, which tends to keep β-glucuronidase activity in check. In contrast, a low-fiber, high-fat, high-simple-sugar diet ∞ often referred to as a “Western diet” ∞ is associated with lower microbial diversity and higher levels of β-glucuronidase activity.

This leads to increased reabsorption of estrogens, raising the body’s total estrogenic burden. For a TRT patient, this is a critical mechanism. A dysbiotic gut, driven by poor fiber intake, can actively work to increase estrogen levels, directly counteracting the therapeutic goal of maintaining a balanced testosterone-to-estrogen ratio and placing a greater demand on aromatase inhibitors.

| Bacterial Phylum | Primary Fiber Substrate | Key Metabolites | Downstream Endocrine Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteroidetes |

Complex Polysaccharides (e.g. Inulin, Pectin) |

Propionate, Acetate |

Improves insulin sensitivity via GPCR signaling; modulates hepatic lipid metabolism. |

| Firmicutes |

Resistant Starch, Beta-Glucans |

Butyrate |

Reduces systemic inflammation by inhibiting histone deacetylase (HDAC); strengthens gut barrier integrity, reducing LPS translocation. |

| Actinobacteria (e.g. Bifidobacterium) |

Fructooligosaccharides (FOS), Galactooligosaccharides (GOS) |

Lactate, Acetate |

Associated with lower β-glucuronidase activity, leading to reduced estrogen recycling. |

SCFA Signaling and Metabolic Endotoxemia

The short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced from fiber fermentation are potent signaling molecules. Butyrate, for instance, is a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor. By inhibiting HDACs, butyrate can epigenetically modulate gene expression, leading to a powerful anti-inflammatory effect. This is critically important in the context of metabolic health. Obesity and insulin resistance, conditions often co-morbid with male hypogonadism (a state sometimes termed metabolic hypogonadism), are characterized by chronic, low-grade inflammation.

A key driver of this inflammation is metabolic endotoxemia. This occurs when the gut barrier becomes compromised (increased intestinal permeability or “leaky gut”), allowing lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, to translocate from the gut lumen into the bloodstream.

Circulating LPS is a potent trigger for the innate immune system, activating Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and initiating a pro-inflammatory cascade. This systemic inflammation is known to suppress hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis function and increase aromatase activity.

The estrobolome, a collection of gut bacteria that metabolize estrogens, directly regulates your body’s estrogen load and is primarily controlled by your fiber intake.

Butyrate produced from fiber fermentation directly counteracts this. It serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes (the cells lining the colon), strengthening the tight junctions between them and enhancing gut barrier integrity. By preventing LPS translocation, a fiber-rich diet that promotes butyrate production directly reduces the inflammatory substrate that can impair hormonal health.

For a TRT patient, this means creating a more favorable internal environment for the therapy to work. It improves insulin sensitivity, which can enhance the body’s response to testosterone, and it reduces the inflammatory drive for aromatization.

Does Fiber Alter Free Androgen Index Calculations?

The clinical assessment of TRT efficacy relies on interpreting laboratory blood tests. While total testosterone is a useful metric, the free or bioavailable testosterone is arguably more important, as this represents the fraction of the hormone that is active. The Free Androgen Index (FAI) is often calculated as (Total Testosterone / SHBG) x 100. It is immediately apparent from this formula that SHBG is a powerful determinant of the final calculated value.

As established, dietary fiber intake can influence hepatic SHBG production. A significant, diet-induced increase in SHBG could lead to a situation where Total Testosterone levels appear adequate or even high-normal, yet the patient’s FAI is suboptimal, and they may still experience symptoms of androgen deficiency.

A clinician who is not considering the patient’s dietary context might misinterpret these results. They might see a high Total T and conclude the dose is sufficient, without appreciating that a high SHBG level is rendering a large portion of that testosterone inactive. This highlights the necessity of a holistic, integrative approach to TRT management.

The “Clinical Translator” recognizes that the lab values are a reflection of a complex biological system, and diet is one of the most powerful inputs into that system. Optimizing a TRT protocol involves personalizing the dose of exogenous testosterone and also providing the patient with dietary strategies to manage SHBG and inflammation, ensuring the administered hormone can function with maximum efficiency.

References

- Dorgan, J. F. et al. “Effects of dietary fat and fiber on plasma and urine androgens and estrogens in men ∞ a controlled feeding study.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 64, no. 6, 1996, pp. 850-855.

- Goldin, B. R. et al. “The effect of dietary fat and fiber on serum estrogen concentrations in premenopausal women under controlled dietary conditions.” Cancer, vol. 74, no. 3 Suppl, 1994, pp. 1125-1131.

- Shin, J. et al. “Serum level of sex steroid hormone is associated with diversity and profiles of human gut microbiome.” Research in Microbiology, vol. 170, no. 4-5, 2019, pp. 192-201.

- Wells, P. M. et al. “The role of the gut microbiome in the effects of dietary fiber on blood pressure.” Nature Reviews Nephrology, vol. 13, no. 2, 2017, pp. 115.

- Guyton, A.C. and Hall, J.E. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 13th ed. Elsevier, 2016.

- Boron, W.F. and Boulpaep, E.L. Medical Physiology. 3rd ed. Elsevier, 2017.

- Heald, A. et al. “The free androgen index is a better marker of androgen status than free testosterone.” Annals of Clinical Biochemistry, vol. 37, no. 5, 2000, pp. 573-576.

- Kwa, M. Plottel, C. S. Blaser, M. J. & Adams, S. “The Estrobolome ∞ The Gut Microbiome and Estrogen.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 108, no. 8, 2016, djw024.

Reflection

You have now seen the intricate biological pathways that connect the fiber in your diet to the hormones central to your vitality. The knowledge that your gut is an endocrine organ, actively participating in your hormonal health, is a powerful realization. The data and mechanisms presented here are tools for understanding.

They are the scientific language that validates the deep connection you have always sensed between how you fuel your body and how you feel and function. Your therapeutic protocol is a critical pillar of your health, a precise intervention to restore balance. Consider your diet, with its rich potential for fiber diversity, as the second pillar.

It is the daily practice that prepares the foundation, reduces systemic noise, and allows your therapy to achieve its fullest and most stable expression. Your journey toward optimal function is a partnership between you, your clinical team, and the profound biological intelligence of your own body. The path forward is one of informed, deliberate choices, where each meal becomes an opportunity to support the very systems you are working to recalibrate.

Glossary

testosterone replacement therapy

dietary fiber

gut microbiome

short-chain fatty acids

butyrate

sex hormone-binding globulin

fiber intake

total testosterone

enterohepatic circulation

aromatase enzyme

anastrozole

systemic inflammation

estrogen levels

fatty acids

inulin

beta-glucans

the estrobolome

estrobolome

produced from fiber fermentation

metabolic hypogonadism

intestinal permeability

lipopolysaccharide