Fundamentals

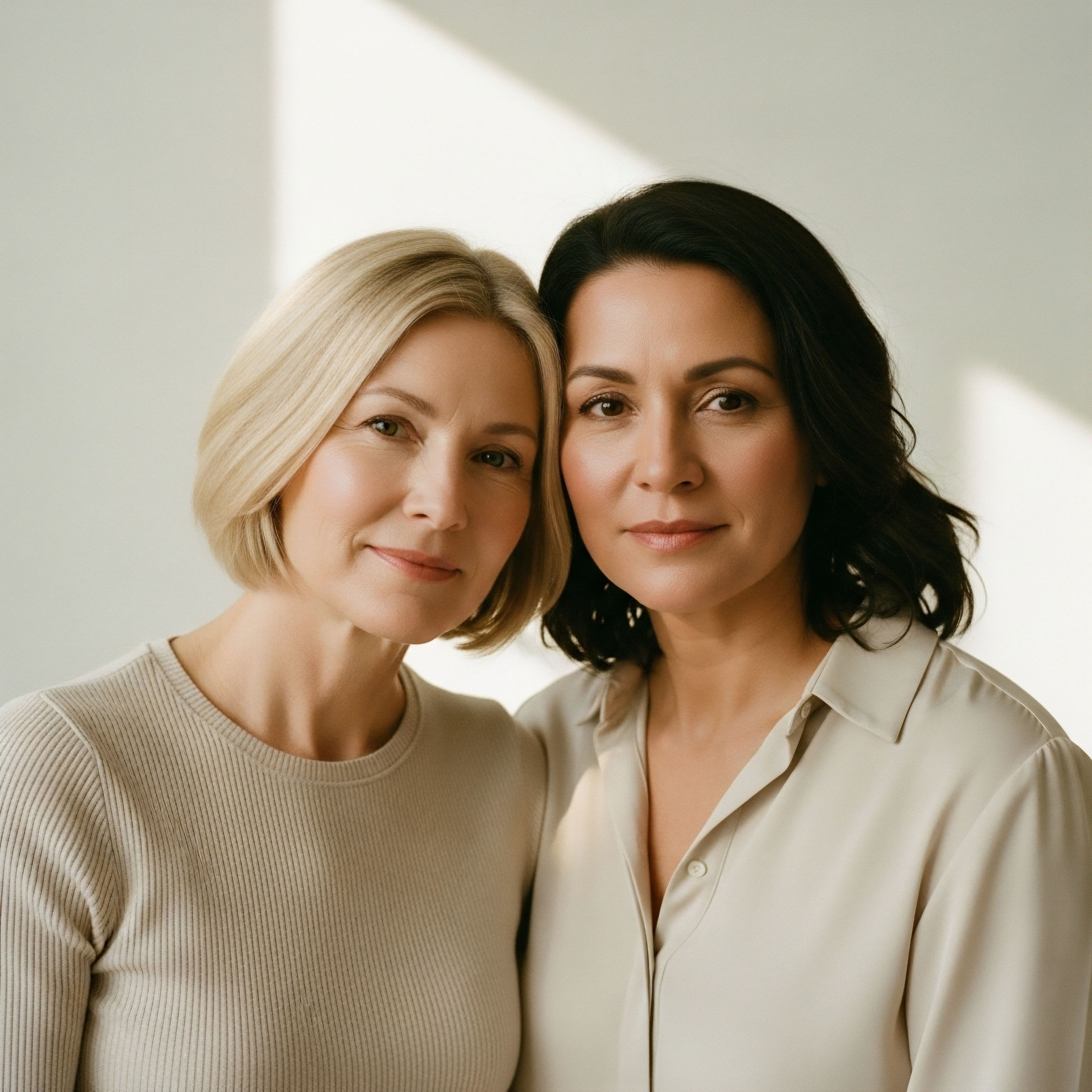

The experience of perimenopause often begins as a subtle, almost imperceptible shift in the body’s internal rhythm. It can manifest as a change in energy that sleep does not seem to restore, a frustrating redistribution of body fat that diet and exercise do not address in the same way they once did, or a new unpredictability in mood and cognitive focus.

These experiences are valid and deeply personal, and they are rooted in the profound biological transition occurring within the endocrine system. At the center of this transition is estrogen, a hormone that functions as a master regulator of female physiology, influencing everything from reproductive cycles to brain health, bone density, and, critically, metabolic function.

Understanding the way our daily choices, particularly the quality of fats we consume, can modulate estrogen’s activity is the first step in reclaiming a sense of control and vitality during this phase of life.

Dietary fats are a primary source of energy and the structural foundation for every cell membrane in the body. They are also the raw materials for producing a class of signaling molecules called eicosanoids, which act as local hormones governing inflammation and cellular communication.

The type of fat consumed directly dictates the type of signaling molecules produced. This means that the fat on your plate becomes part of a complex biochemical conversation inside your body, a conversation that powerfully influences how estrogen is synthesized, used, and eliminated. This process of estrogen metabolism is a continuous cycle, and its efficiency determines whether hormonal balance is maintained or disrupted.

The quality of dietary fat is a foundational input that directly informs the body’s ability to manage estrogen signaling and metabolic health during perimenopause.

The Architectural Role of Dietary Fats

To appreciate the impact of fat quality, one must first understand the primary categories of fatty acids and their distinct physiological roles. These molecules are categorized based on their chemical structure, which in turn dictates their function within the body’s intricate systems. Each type of fat you consume contributes differently to cellular health, inflammatory balance, and hormonal regulation.

- Saturated Fats ∞ Found predominantly in animal products like red meat and full-fat dairy, as well as in tropical oils like coconut and palm oil. These fats are “saturated” with hydrogen atoms and are typically solid at room temperature. They are a source of energy and play a role in cellular membrane structure. Their overconsumption, particularly from processed sources, is associated with increased low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and a pro-inflammatory state, which can burden the metabolic systems responsible for processing hormones.

- Monounsaturated Fats (MUFAs) ∞ Abundant in olive oil, avocados, and certain nuts like almonds and macadamias. MUFAs are characterized by a single double bond in their carbon chain. They are a cornerstone of the Mediterranean diet and are recognized for their role in supporting cardiovascular health by improving cholesterol profiles and reducing inflammation. Their presence helps to create flexible, healthy cell membranes, which is vital for efficient hormone receptor function.

- Polyunsaturated Fats (PUFAs) ∞ These fats have two or more double bonds in their structure and are found in sources like fatty fish (salmon, mackerel, sardines), walnuts, flaxseeds, and sunflower oil. This category includes two essential families that the body cannot produce on its own ∞ Omega-3 and Omega-6 fatty acids. The balance between these two families is a critical determinant of the body’s inflammatory status. Modern Western diets are often excessively high in Omega-6s (from vegetable oils and processed foods) and deficient in Omega-3s, a state of affairs that promotes systemic inflammation and can disrupt sensitive hormonal pathways.

How Does Fat Quality Influence Estrogen Directly?

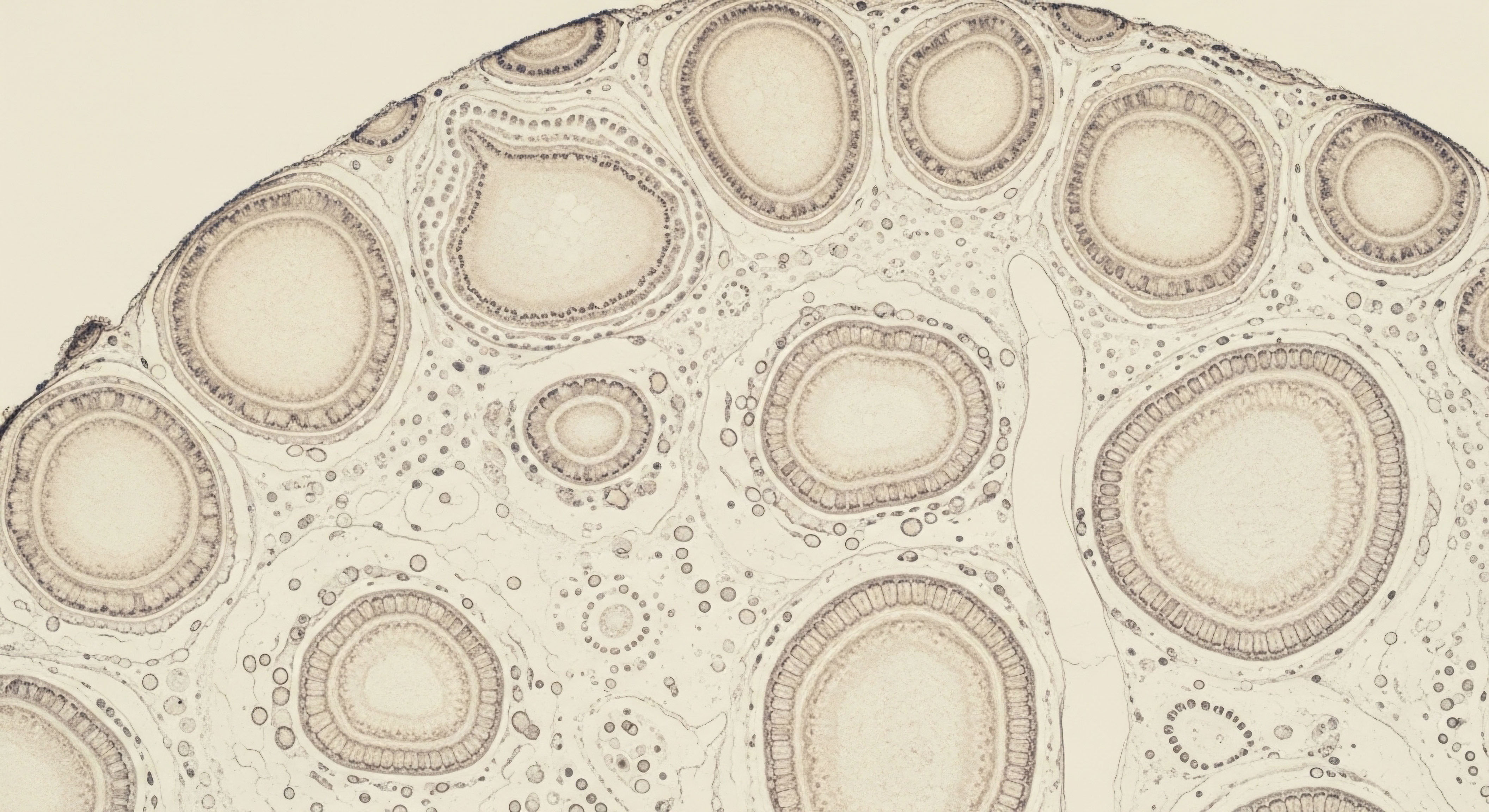

The connection between dietary fat and estrogen metabolism is multifaceted. Fat tissue itself, known as adipose tissue, is an endocrine organ that produces and stores estrogen. An increase in body fat, particularly visceral fat around the abdomen, can lead to higher circulating levels of estrogen, a condition that may contribute to symptoms like heavy bleeding and breast tenderness during perimenopause. The quality of dietary fat influences both the amount of adipose tissue and its inflammatory activity.

Furthermore, the liver is the primary site for estrogen detoxification. This organ processes used estrogen through a two-phase system to prepare it for excretion. A diet high in processed, pro-inflammatory fats can place a significant burden on the liver, compromising its ability to perform this vital function efficiently.

Conversely, a diet rich in anti-inflammatory fats like Omega-3s supports liver health and the enzymatic pathways required for breaking down estrogen, facilitating its removal from the body and preventing its harmful recirculation.

Intermediate

As the body enters perimenopause, the predictable hormonal symphony of the menstrual cycle gives way to a more improvisational and often chaotic performance. The fluctuations in estrogen and progesterone levels become more erratic, leading to a cascade of physiological responses. Understanding the mechanisms through which dietary fat quality can bring a measure of stability to this system is empowering.

It moves the conversation from generic dietary advice to a targeted biochemical strategy. The influence of fats extends deep into the cellular machinery, affecting hormone receptor sensitivity, the production of inflammatory messengers, and the efficiency of detoxification pathways. These are the levers that can be consciously adjusted through nutritional choices to modulate the perimenopausal experience.

The Cellular Conversation Eicosanoids and Inflammation

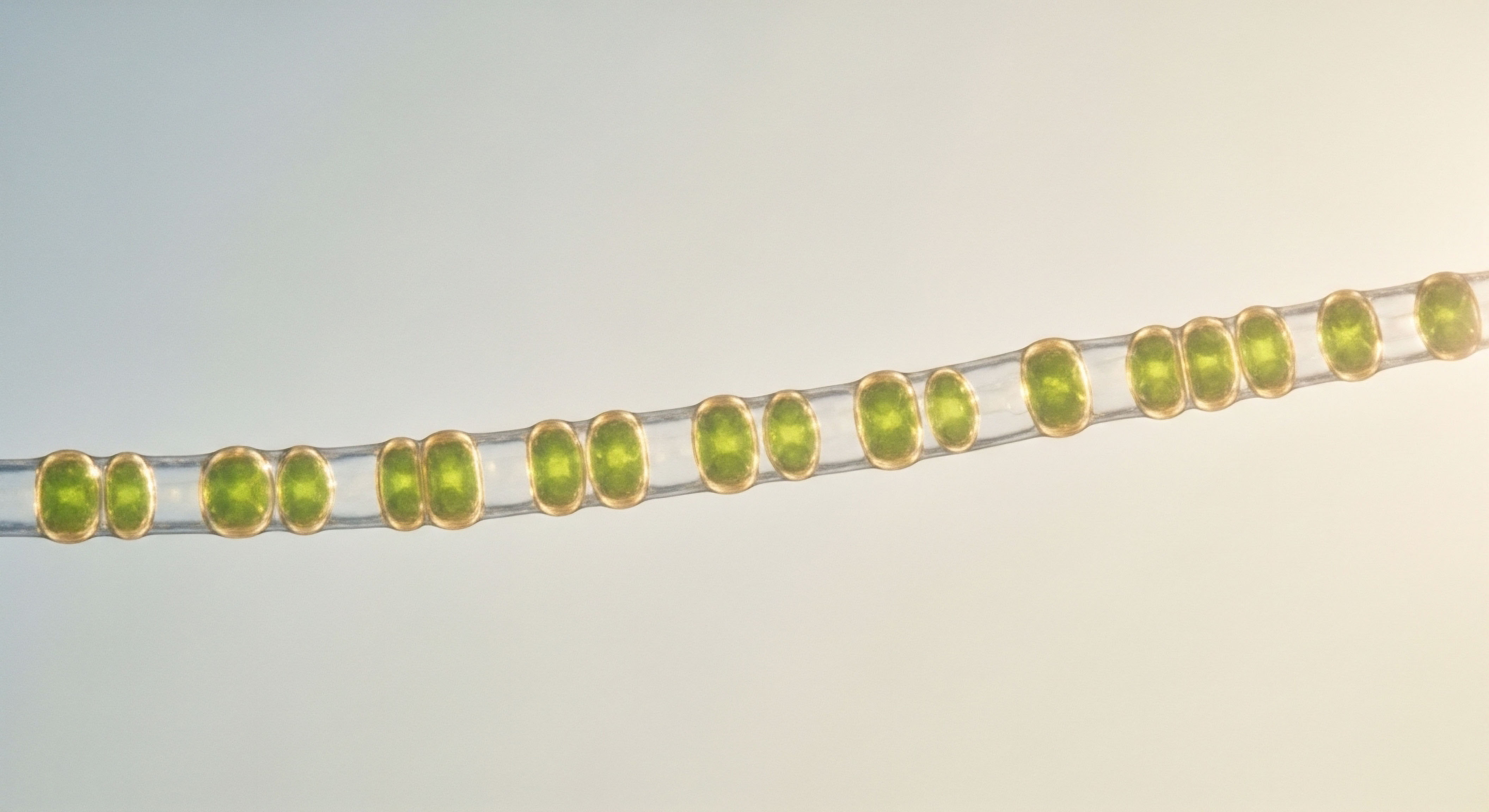

Every cell membrane is a dynamic, fluid structure, and its composition is a direct reflection of the fats consumed in the diet. Embedded within these membranes are polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), which serve as the precursors to a powerful class of signaling molecules known as eicosanoids.

These molecules act as local regulators, orchestrating the body’s response to injury and infection. The critical insight here is that the two families of essential PUFAs, Omega-6 and Omega-3, give rise to eicosanoids with opposing effects.

- Omega-6 Derived Eicosanoids ∞ The dominant Omega-6 fatty acid in the Western diet is arachidonic acid (AA). When cellular stress occurs, AA is converted into signaling molecules that are generally pro-inflammatory. This inflammatory response is necessary for short-term healing, but when chronically elevated due to a high intake of Omega-6-rich vegetable oils and processed foods, it creates a state of low-grade systemic inflammation. This environment can exacerbate perimenopausal symptoms like joint pain, mood instability, and metabolic dysfunction.

- Omega-3 Derived Eicosanoids ∞ The Omega-3 fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), found in fatty fish, are converted into eicosanoids that are actively anti-inflammatory and resolving. They do not just reduce inflammation; they help to actively resolve it, signaling the completion of the healing process. By increasing the intake of Omega-3s, one can shift the balance of eicosanoid production, creating a less inflammatory internal environment. This biochemical shift can help soothe the heightened sensitivity of the perimenopausal period and support more balanced hormonal function.

The ratio of Omega-6 to Omega-3 fatty acids in the diet directly determines the inflammatory tone of the body, a critical factor in managing perimenopausal symptoms.

Estrogen Detoxification a Two-Phase Process

Once estrogen has delivered its message to a cell, it must be deactivated and eliminated to prevent its accumulation. This vital task is performed primarily by the liver in a two-step process. The quality of dietary fats has a profound impact on the efficiency of both phases.

Phase I Detoxification the Activation Pathway

In Phase I, enzymes known as the Cytochrome P450 family chemically modify the estrogen molecule. This process, called hydroxylation, creates different estrogen metabolites. Some of these metabolites are benign, while others can be more potent and potentially harmful if not properly cleared.

A healthy liver, supported by adequate nutrients, can favor the creation of “good” metabolites like 2-hydroxyestrone. Factors that impair liver function, such as a high intake of saturated and trans fats, can skew this process towards the production of more problematic metabolites like 16-alpha-hydroxyestrone.

Phase II Detoxification the Conjugation Pathway

In Phase II, the metabolites created in Phase I are attached to another molecule (a process called conjugation) to make them water-soluble and ready for excretion via urine or bile. This step is dependent on specific nutrients and enzymatic processes like glucuronidation and sulfation.

A diet rich in anti-inflammatory fats and phytonutrients supports these conjugation pathways. When Phase II is sluggish, which can be exacerbated by a stressed liver, the reactive metabolites from Phase I can build up, leading to cellular damage and contributing to symptoms of estrogen dominance.

The table below outlines how different dietary fat profiles can influence these critical metabolic and detoxification systems.

| Dietary Fat Profile | Impact on Inflammatory Balance | Influence on Estrogen Metabolism |

|---|---|---|

| High Omega-6 / Low Omega-3 | Promotes the production of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids, leading to chronic low-grade inflammation. | Can impair liver function, potentially skewing Phase I detoxification toward more problematic estrogen metabolites and slowing Phase II clearance. |

| High Saturated & Trans Fats | Contributes to systemic inflammation and can increase LDL cholesterol, placing a burden on metabolic systems. | May compromise liver health and insulin sensitivity, indirectly leading to higher circulating estrogen levels from adipose tissue. |

| High Monounsaturated Fats (MUFAs) | Reduces inflammation and supports healthy cholesterol levels, creating a favorable metabolic environment. | Supports overall liver health and cell membrane fluidity, enhancing hormone receptor function and detoxification efficiency. |

| High Omega-3 (EPA & DHA) | Actively anti-inflammatory and resolving, helping to balance the effects of Omega-6 fatty acids. | Directly supports the reduction of systemic inflammation, easing the burden on the liver and promoting healthier estrogen metabolite profiles. |

How Does This Relate to Clinical Protocols?

For women considering or currently using hormonal optimization protocols, such as low-dose testosterone or progesterone therapy, understanding this dietary influence is paramount. A pro-inflammatory internal environment driven by poor fat quality can work against the goals of these therapies.

For instance, chronic inflammation can blunt the sensitivity of hormone receptors, meaning the body may not respond as effectively to the therapy provided. By optimizing dietary fat intake to favor an anti-inflammatory state, a woman can create a more receptive and balanced internal terrain. This allows hormonal therapies to function more efficiently, supporting goals like improved energy, mood stabilization, and enhanced cognitive function with greater success.

Academic

A sophisticated examination of the relationship between dietary fat and estrogen metabolism in perimenopausal women requires a systems-biology perspective, moving beyond simple dietary recommendations to the intricate molecular pathways that connect the gut, the liver, and the endocrine system.

The central nexus for this interaction is the gut microbiome and its profound influence on the enterohepatic circulation of estrogens. This pathway represents a critical control point where microbial activity, directly shaped by dietary inputs, can determine the systemic burden of active estrogen. The quality of dietary fat is a primary driver of the composition and metabolic activity of the gut microbiota, thereby holding significant sway over hormonal balance during the perimenopausal transition.

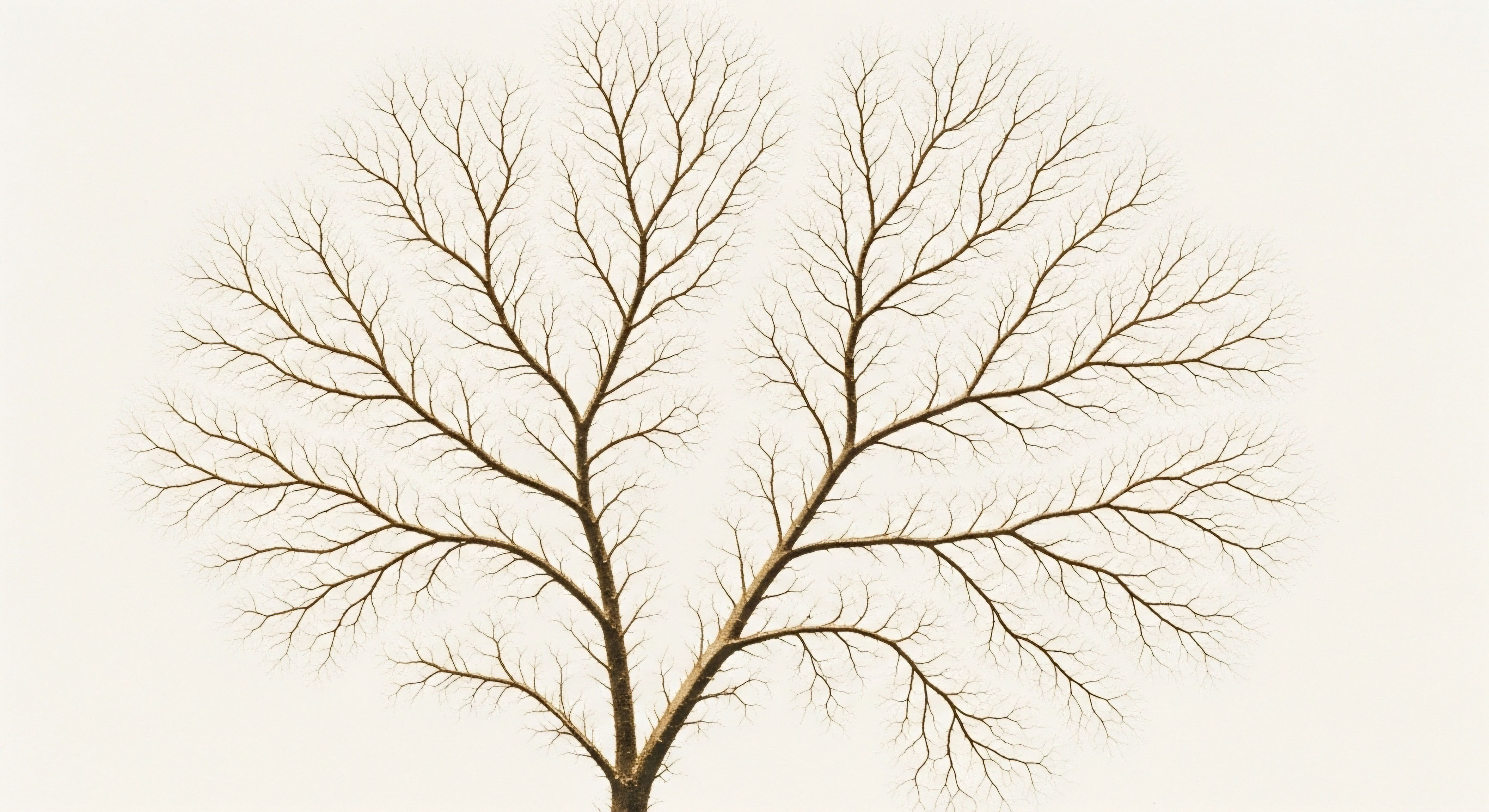

The Enterohepatic Circulation of Estrogens

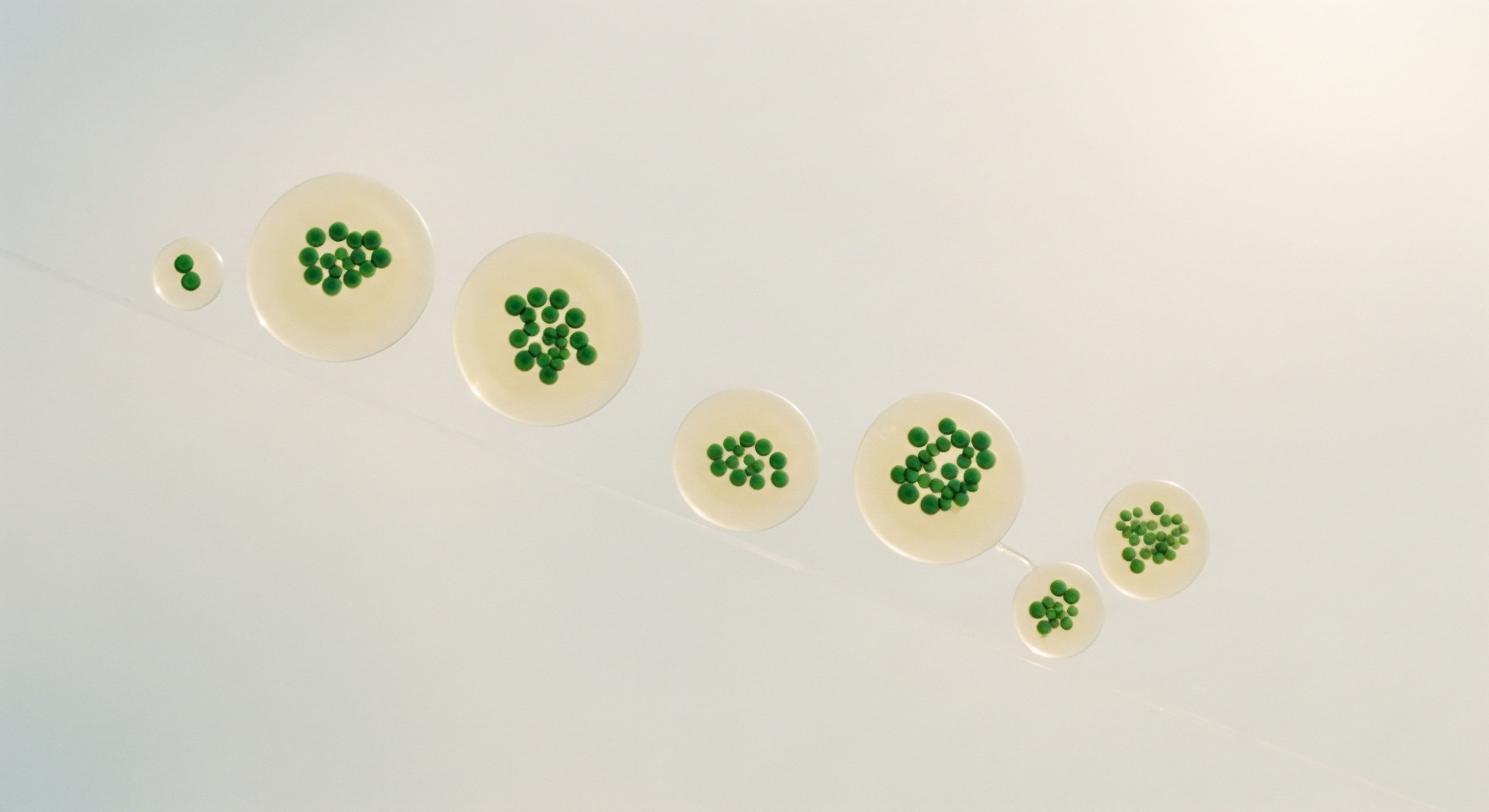

The liver metabolizes estrogens by conjugating them, primarily through glucuronidation, to render them water-soluble for excretion. These conjugated estrogens are then secreted into the bile, which flows into the intestinal tract. In a balanced system, these inactive estrogens would be eliminated from the body in the feces.

There exists, however, a recycling pathway. Certain bacteria within the gut microbiome produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. This enzyme can deconjugate, or “reactivate,” the estrogens in the gut, severing the bond that made them water-soluble. Once liberated, these now active estrogens can be reabsorbed through the intestinal wall back into the bloodstream, a process known as enterohepatic circulation.

During perimenopause, when endogenous estrogen production becomes erratic, an overactive enterohepatic circulation pathway can contribute significantly to the total estrogen load, potentially exacerbating symptoms of estrogen dominance such as breast tenderness, heavy menstrual flow, and uterine fibroid growth. The activity of microbial beta-glucuronidase is therefore a key variable in estrogen homeostasis.

The gut microbiome, through its enzymatic capacity to reactivate estrogens, functions as a critical regulator of the body’s total estrogen exposure.

What Governs the Activity of Beta-Glucuronidase?

The collection of gut microbes with the genetic capacity to produce beta-glucuronidase is termed the “estrobolome.” The composition and activity of this estrobolome are highly sensitive to long-term dietary patterns. Diets high in saturated fats and low in fiber, characteristic of the standard Western diet, are associated with a microbial profile that exhibits higher beta-glucuronidase activity.

This dietary pattern promotes a state of dysbiosis, favoring the growth of bacterial species that drive this reactivation pathway. The result is a greater reabsorption of estrogen from the gut, increasing the body’s total exposure and placing a greater burden on the liver’s detoxification systems.

Conversely, diets rich in fiber and beneficial fats, such as the polyunsaturated Omega-3s and monounsaturated fats found in the Mediterranean diet, foster a more diverse and balanced microbiome. Soluble fibers from sources like legumes, oats, and vegetables provide the substrate for beneficial bacteria to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate.

Butyrate is the primary fuel for the cells lining the colon and has been shown to have an inhibitory effect on the proliferation of certain pathogenic bacteria, thereby helping to modulate the activity of the estrobolome. Omega-3 fatty acids contribute to this effect by reducing intestinal inflammation and supporting the integrity of the gut barrier, further shaping a favorable microbial environment.

The table below details the interaction between dietary components, the gut microbiome, and estrogen metabolism.

| Dietary Component | Effect on Gut Microbiome | Impact on Enterohepatic Circulation | Net Effect on Estrogen Load |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Saturated Fat / Low Fiber | Promotes dysbiosis; increases populations of bacteria with high beta-glucuronidase activity. | Increases the deconjugation of estrogens in the gut, enhancing their reabsorption. | Increases systemic estrogen burden. |

| High Omega-3 PUFAs | Reduces gut inflammation; supports a healthy gut barrier and microbial diversity. | Modulates the microbial environment, potentially reducing overall beta-glucuronidase activity. | Helps maintain a balanced estrogen load. |

| High Soluble Fiber | Promotes growth of beneficial bacteria; increases production of SCFAs like butyrate. | Helps to lower the pH of the gut and provides fuel for a healthy colon, indirectly suppressing undesirable bacterial activity. | Reduces estrogen reabsorption and promotes excretion. |

| High Monounsaturated Fats | Supports a balanced inflammatory response and overall microbial diversity. | Contributes to a healthy gut environment that is less conducive to high beta-glucuronidase activity. | Supports balanced estrogen metabolism. |

Can This Pathway Be Targeted Therapeutically?

This mechanistic understanding provides a clear rationale for specific, evidence-based dietary interventions for perimenopausal women. The goal is to shift the composition of the estrobolome to reduce beta-glucuronidase activity and, consequently, estrogen reactivation. This is achieved by increasing the intake of fiber-rich plant foods and prioritizing anti-inflammatory fats.

This approach aligns perfectly with the principles of hormonal optimization protocols. For a woman undergoing therapy with bioidentical progesterone to counteract the effects of fluctuating estrogen, a dietary strategy that minimizes the reabsorption of endogenous estrogen from the gut is highly synergistic. It ensures that the therapeutic protocol is not fighting against a hidden source of hormonal input, allowing for more predictable and stable outcomes.

Furthermore, this knowledge underscores the interconnectedness of metabolic and hormonal health. The same dietary patterns that support a healthy estrobolome also improve insulin sensitivity and reduce systemic inflammation, addressing other common challenges of the perimenopausal period. This systems-based approach, which views dietary fat quality as a tool to modulate the gut-hormone axis, represents a sophisticated and highly effective strategy for navigating the complexities of perimenopausal health.

References

- Fuhrman, B. J. et al. “Estrogen Metabolism and Risk of Breast Cancer in Postmenopausal Women.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 104, no. 4, 2012, pp. 326-39.

- Cleary, M. P. and M. E. Grossmann. “Minireview ∞ Obesity and Breast Cancer ∞ The Estrogen Connection.” Endocrinology, vol. 150, no. 6, 2009, pp. 2537-42.

- Baker, J. M. et al. “Estrogen-gut Microbiome Axis ∞ Physiological and Clinical Implications.” Maturitas, vol. 103, 2017, pp. 45-53.

- Simkin, D. R. “The Role of Diet and Nutrition in Menopause.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 107, no. 8, 2022, pp. e3151-e3168.

- Salini, T. et al. “The Importance of Nutrition in Menopause and Perimenopause ∞ A Review.” Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 9, 2021, p. 3002.

- Ko, S.-H. and S.-H. Kim. “Menopause-Associated Lipid Metabolic Disorders and Foods Beneficial for Postmenopausal Women.” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 1, 2020, p. 202.

- “High Estrogen.” Cleveland Clinic, 9 Feb. 2022.

- “10 Natural Ways to Balance Your Hormones.” Healthline, 15 Aug. 2022.

- “Perimenopause ∞ Rocky road to menopause.” Harvard Health Publishing, 1 July 2020.

- Davis, S. R. et al. “Testosterone for Low Libido in Postmenopausal Women ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, vol. 7, no. 12, 2019, pp. 939-48.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Internal Compass

The information presented here offers a map of the intricate biological landscape of perimenopause, detailing how the choices you make at the dinner table translate into molecular signals that shape your daily experience. This knowledge is a powerful tool, shifting the perspective from one of passive endurance to one of active participation in your own well-being.

The purpose of this deep exploration is to equip you with a more nuanced understanding of your body’s inner workings. Consider the patterns in your own life. Think about the times you have felt most vital and clear-headed, and the times you have felt depleted or inflamed.

What were the inputs during those periods? This journey of self-awareness, of connecting your lived experience to the biological principles that govern it, is the essential first step. The path forward is one of partnership ∞ between you and your body, and between you and a knowledgeable clinical guide who can help you interpret your unique signals and craft a personalized strategy to navigate this profound and transformative stage of life.

Glossary

signaling molecules

dietary fats

estrogen metabolism

hormonal balance

fat quality

fatty acids

monounsaturated fats

systemic inflammation

adipose tissue

dietary fat

dietary fat quality

eicosanoids

omega-3 fatty acids

enterohepatic circulation

gut microbiome