Fundamentals

You feel it in your bones, a deep exhaustion that coffee can’t touch. It’s more than just being tired; it’s a depletion of your vitality, a sense of running on fumes that affects your mood, your focus, and your drive. When you consistently sacrifice sleep, you are not just losing hours of rest.

You are systematically dismantling the intricate hormonal machinery that governs your energy and well-being. The connection between chronic sleep deprivation and a measurable decline in androgens, particularly testosterone, is a direct and biological one. This is a physiological reality, a sequence of events occurring at a cellular level that directly translates into the fatigue and diminished capacity you may be experiencing.

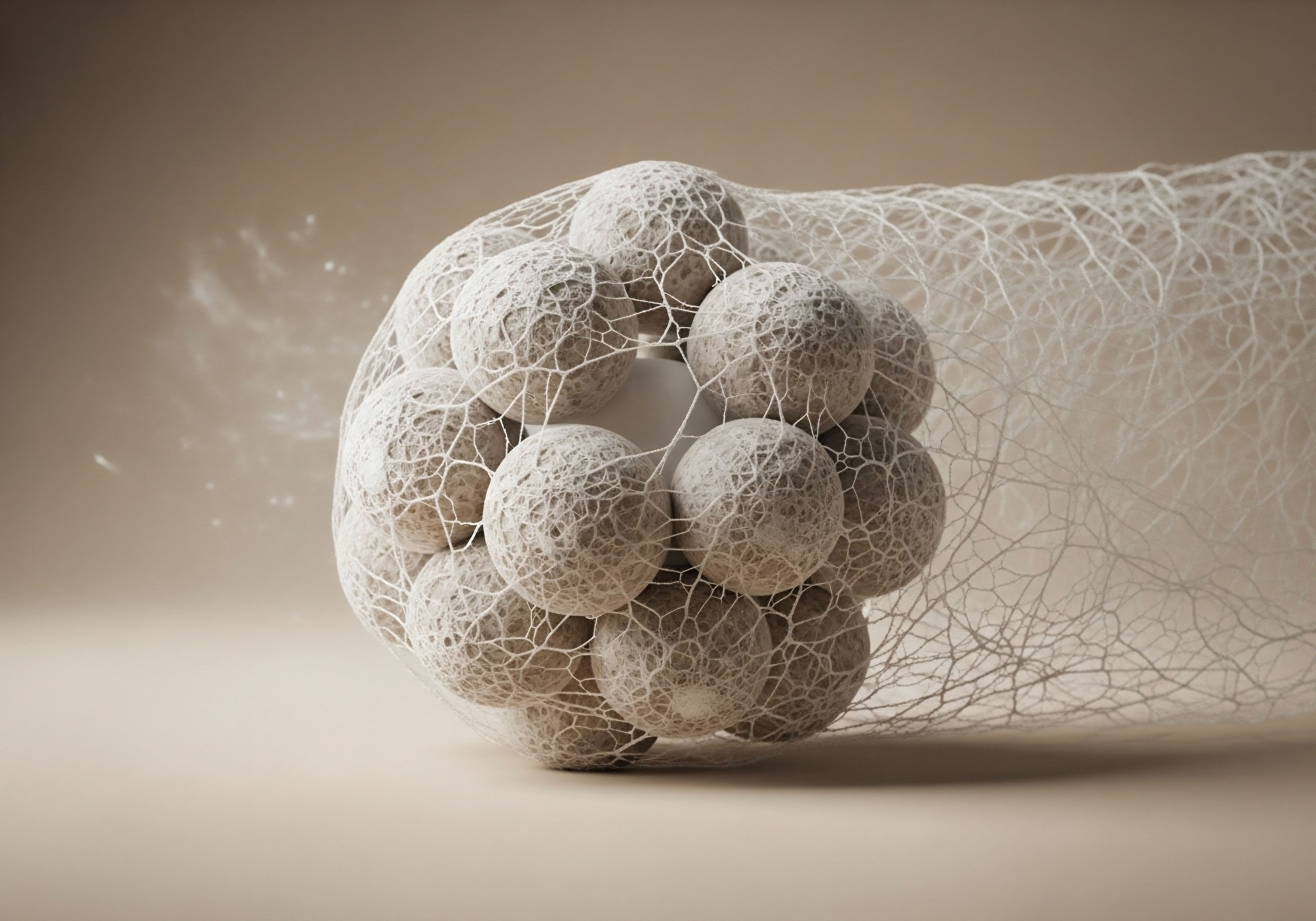

Your body’s production of testosterone is profoundly linked to your sleep cycles. The majority of daily testosterone release in men occurs during sleep, specifically during the deep, restorative stages. Think of your endocrine system as a meticulously synchronized orchestra.

The conductor, the hypothalamus in your brain, sends signals to the pituitary gland, which in turn directs the testes to produce testosterone. This entire performance, known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, is calibrated to your sleep-wake rhythm. When sleep is cut short, the conductor’s signals become weak and disorganized. The orchestra plays out of tune, and the result is a suppressed output of its most vital instruments.

A persistent lack of sleep directly interferes with the natural, nightly surge of testosterone production essential for male vitality.

The symptoms of androgen deficiency and sleep deprivation create a considerable overlap, which can make it difficult to distinguish one from the other. Low energy, reduced libido, poor concentration, and even increased sleepiness are the clinical signs of both conditions. This is because the underlying hormonal disruption affects the same systems.

The fatigue from low testosterone feels remarkably similar to the fatigue from a lack of sleep because, in many ways, they stem from the same root cause ∞ a body that has been denied a fundamental process for regeneration and hormonal regulation. Understanding this link is the first step toward recognizing that the way you feel is a logical, physiological response to an unsustainable pattern.

One study on young, healthy men demonstrated that restricting sleep to five hours per night for just one week decreased daytime testosterone levels by 10% to 15%. To put this into perspective, normal aging is associated with a testosterone decline of about 1% to 2% per year.

This means that a single week of insufficient sleep can age a man’s hormonal profile by a decade or more. This is a measurable, significant drop that underscores the profound impact of sleep on your body’s ability to produce the very hormones that make you feel strong, focused, and capable.

Intermediate

To comprehend how sleep loss translates into a hormonal deficit, we must examine the architecture of the endocrine system, specifically the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This system is a sophisticated feedback loop. The hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) in pulses. This GnRH pulse signals the pituitary gland to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH).

LH then travels through the bloodstream to the Leydig cells in the testes, stimulating them to produce and secrete testosterone. Testosterone itself then sends a feedback signal back to the hypothalamus and pituitary, modulating the release of GnRH and LH to maintain a balanced state. This entire process is deeply entrained with our circadian rhythm, and a significant portion of its activity is designated to occur during sleep.

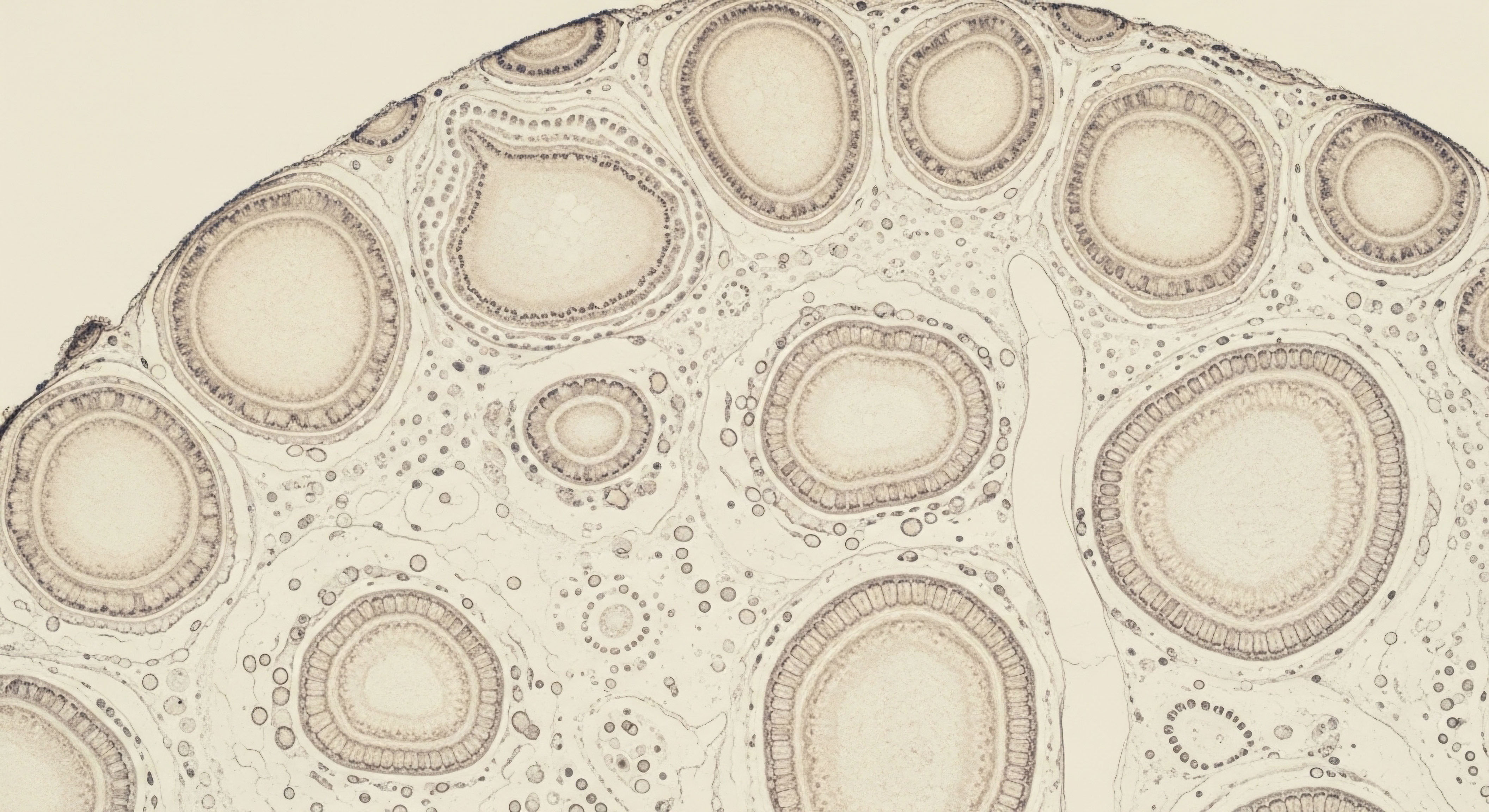

The Critical Role of Sleep Architecture

The nightly rise in testosterone is not simply a function of being unconscious; it is dependent on the quality and structure of your sleep. At least three hours of normal sleep architecture are required for the testosterone surge to occur.

Studies have shown that the increase in testosterone is tied to the onset of sleep, particularly the deeper, non-REM stages. When sleep is fragmented or shortened, these critical stages are compromised. For instance, in one study, men subjected to sleep restriction lost a significant amount of stage-2 and REM sleep.

This disruption prevents the HPG axis from running its full nightly cycle, leading to a blunted morning peak in testosterone. The result is lower overall testosterone exposure throughout the following day.

The intricate signaling between the brain and gonads, which drives testosterone production, is optimally active during consolidated, quality sleep.

The stress hormone cortisol also plays a role in this dynamic. Chronic sleep deprivation is a physiological stressor, and like other stressors, it can lead to elevated cortisol levels. Cortisol and testosterone often have an inverse relationship; as one rises, the other tends to fall.

Elevated cortisol can directly inhibit the function of the HPG axis at multiple levels, suppressing GnRH release from the hypothalamus and reducing the sensitivity of the testes to LH. This creates a dual-pronged assault on your androgen levels ∞ sleep loss directly impairs the testosterone production cycle while simultaneously creating a hormonal environment that is actively hostile to it.

Differentiating Causes and Effects

From a clinical standpoint, it is vital to determine whether low testosterone is a direct consequence of poor sleep or if both are symptoms of an underlying issue, such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). OSA, a condition where breathing repeatedly stops and starts during sleep, causes severe sleep fragmentation and oxygen desaturation.

Both of these factors are known to suppress testosterone levels. However, research suggests that the primary driver of low testosterone in men with OSA is often the associated obesity, which independently disrupts hormonal balance. Addressing the sleep disorder is a critical first step.

In cases of late-onset hypogonadism, which involves a gradual decline in testosterone with age, poor sleep is a common symptom. This can create a vicious cycle where low testosterone impairs sleep quality, and impaired sleep further suppresses testosterone production.

Clinical Evaluation of Sleep Related Androgen Deficiency

When a patient presents with symptoms of low testosterone, a thorough evaluation will always include an assessment of sleep habits and quality. This involves more than just asking about hours slept. A clinician will inquire about sleep consistency, awakenings during the night, and daytime sleepiness.

Lab work will measure total and free testosterone, LH, and potentially cortisol levels. If sleep-disordered breathing is suspected, a sleep study may be recommended. This comprehensive approach ensures that the treatment plan addresses the root cause, whether it’s implementing lifestyle changes to improve sleep hygiene, treating a condition like sleep apnea, or considering hormonal optimization protocols if a primary androgen deficiency is confirmed.

The following table outlines the key hormonal players and how their levels are affected by sleep deprivation, providing a clearer picture of the systemic impact.

| Hormone | Function in Androgen Production | Effect of Sleep Deprivation |

|---|---|---|

| Testosterone | The primary male androgen, crucial for libido, muscle mass, and energy. | Levels are significantly decreased due to disruption of the nightly production surge. |

| Luteinizing Hormone (LH) | Released by the pituitary to signal the testes to produce testosterone. | Pulsatile release is dampened, leading to reduced testicular stimulation. |

| Cortisol | A primary stress hormone. | Levels can become elevated, which actively suppresses the HPG axis. |

| Growth Hormone (GH) | Released during deep sleep, supports tissue repair and metabolic health. | Secretion is impaired, affecting overall recovery and vitality. |

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of sleep-induced androgen deficiency requires a granular look at the neuroendocrine and metabolic pathways at play. The relationship extends beyond a simple correlation between sleep duration and testosterone levels; it involves the intricate timing of hormonal pulses, the integrity of specific sleep stages, and the secondary effects of metabolic dysregulation.

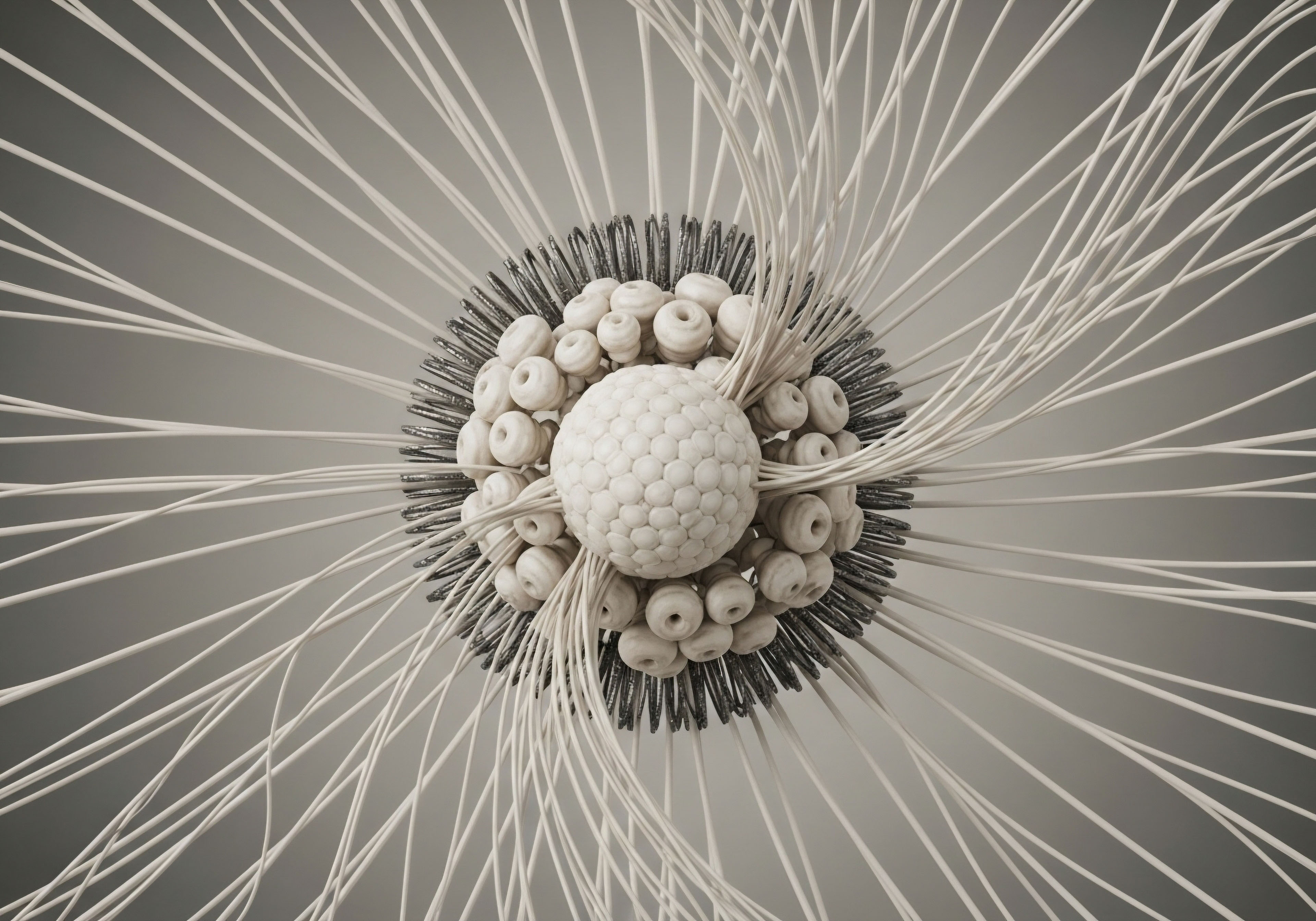

The HPG axis does not operate in a vacuum. Its function is deeply integrated with the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs the stress response, and is modulated by various neuropeptides and neurotransmitters that are themselves influenced by sleep.

Neuroendocrine Mechanisms of Suppression

The pulsatility of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus is the master regulator of the HPG axis. Research in animal models provides insight into the mechanisms of suppression. Studies on rats subjected to acute sleep deprivation have shown a marked decrease in Luteinizing Hormone (LH) levels, with a subsequent drop in testosterone, indicating a disruption at the pituitary level.

Interestingly, in these studies, the expression of kisspeptin, a critical upstream regulator of GnRH, was not significantly altered, suggesting that the primary insult from acute sleep loss may occur downstream from the initial GnRH signal, possibly affecting pituitary sensitivity to GnRH. This points to a state of secondary hypogonadism, where the testes are capable of producing testosterone but are not receiving the proper signals to do so.

Furthermore, the timing of sleep appears to be a critical variable. One study found that sleep restriction during the second half of the night, which involves early awakening, had a more pronounced suppressive effect on morning testosterone concentrations than sleep loss in the early part of the night.

This suggests that the hormonal restoration processes are particularly active during the later stages of a full sleep cycle, and that modern habits of early rising for work may be especially detrimental to the HPG axis.

The Interplay of Inflammation and Metabolic Health

Chronic sleep deprivation is a state of low-grade systemic inflammation. Sleep loss is associated with an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-alpha). These cytokines are known to have an inhibitory effect on testicular steroidogenesis and can suppress the HPG axis at the hypothalamic and pituitary levels.

This inflammatory state also contributes to insulin resistance, another key factor in androgen regulation. Insulin resistance and the associated metabolic syndrome and obesity are strongly linked to lower testosterone levels. Adipose tissue, particularly visceral fat, is metabolically active and expresses the enzyme aromatase, which converts testosterone into estrogen. Increased aromatase activity can shift the androgen-to-estrogen ratio, further contributing to a hypogonadal state.

Sleep deprivation creates a cascade of neuroendocrine and inflammatory disruptions that collectively suppress the body’s ability to maintain healthy androgen levels.

The following table details the findings of key studies in the field, illustrating the measurable impact of sleep restriction on hormonal parameters.

| Study Focus | Sleep Protocol | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Sleep Restriction | 1 week of 5 hours of sleep per night. | 10-15% decrease in daytime testosterone levels in young, healthy men. | |

| HPG Axis in Animal Models | 72 hours of sleep deprivation in rats. | Marked decrease in LH and testosterone, suggesting pituitary hypogonadism. | |

| Sleep Timing | Sleep restricted to the first half of the night vs. the second half. | Early awakening (sleep loss in the second half of the night) caused a greater reduction in morning testosterone. |

What Are the Implications for Therapeutic Interventions?

Understanding these mechanisms has direct implications for clinical practice. For individuals presenting with symptoms of androgen deficiency, a comprehensive approach is necessary. While Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) can restore serum testosterone levels, it may not address the underlying pathology if sleep deprivation is the primary cause.

Protocols that aim to restore hormonal balance should consider therapies that improve sleep quality and duration. For example, peptide therapies using agents like Ipamorelin or CJC-1295 are designed to stimulate the body’s own production of Growth Hormone, which is also released during deep sleep and can improve sleep architecture.

For some individuals, a growth hormone secretagogue like MK-677, which mimics the hormone ghrelin, can also enhance sleep quality, although its primary action is on the GH axis, not the HPG axis directly. Ultimately, restoring the body’s natural circadian rhythm and sleep patterns is a foundational element of any protocol aimed at optimizing endocrine function and reclaiming vitality.

- Primary Hypogonadism ∞ This refers to a failure of the testes to produce testosterone despite adequate signaling from the pituitary gland. It is not the typical presentation for sleep-related androgen deficiency.

- Secondary Hypogonadism ∞ This condition arises from a problem in the hypothalamus or pituitary gland, leading to insufficient stimulation of the testes. Research suggests that sleep deprivation induces a state of secondary hypogonadism.

- Functional Hypogonadism ∞ This term is sometimes used to describe a state where testosterone levels are low due to factors like obesity, poor diet, or, in this context, chronic sleep loss. Addressing the underlying functional cause can often restore normal hormonal production.

References

- Lee, D. S. Choi, J. B. & Sohn, D. W. (2019). Impact of Sleep Deprivation on the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis and Erectile Tissue. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(1), 5 ∞ 16.

- Leproult, R. & Van Cauter, E. (2011). Effect of 1 week of sleep restriction on testosterone levels in young healthy men. JAMA, 305(21), 2173 ∞ 2174.

- Schmid, S. M. Hallschmid, M. Jauch-Chara, K. Lehnert, H. & Schultes, B. (2012). Sleep timing may modulate the effect of sleep loss on testosterone. Clinical Endocrinology, 77(5), 749 ∞ 754.

- University of Chicago Medical Center. (2011). Sleep loss dramatically lowers testosterone in healthy young men. ScienceDaily. Retrieved from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/05/110531162142.htm

- Wittert, G. (2014). The relationship between sleep disorders and testosterone in men. Asian Journal of Andrology, 16(2), 262 ∞ 265.

Reflection

Recalibrating Your Internal Clock

The data and mechanisms presented here provide a clear, biological basis for the symptoms you may be experiencing. The fatigue, the mental fog, the loss of drive ∞ these are not failures of willpower. They are the predictable physiological consequences of a system being denied one of its most fundamental requirements for regulation and repair.

This knowledge is the starting point. It shifts the perspective from one of enduring a collection of frustrating symptoms to one of understanding a specific, addressable biological state. The path forward begins with a foundational question ∞ what steps can you take, starting tonight, to protect and prioritize the time your body needs to rebuild its hormonal architecture?

Your personal health journey is a process of recalibration, and recognizing the profound role of sleep is the first, most powerful turn of the dial.