Fundamentals

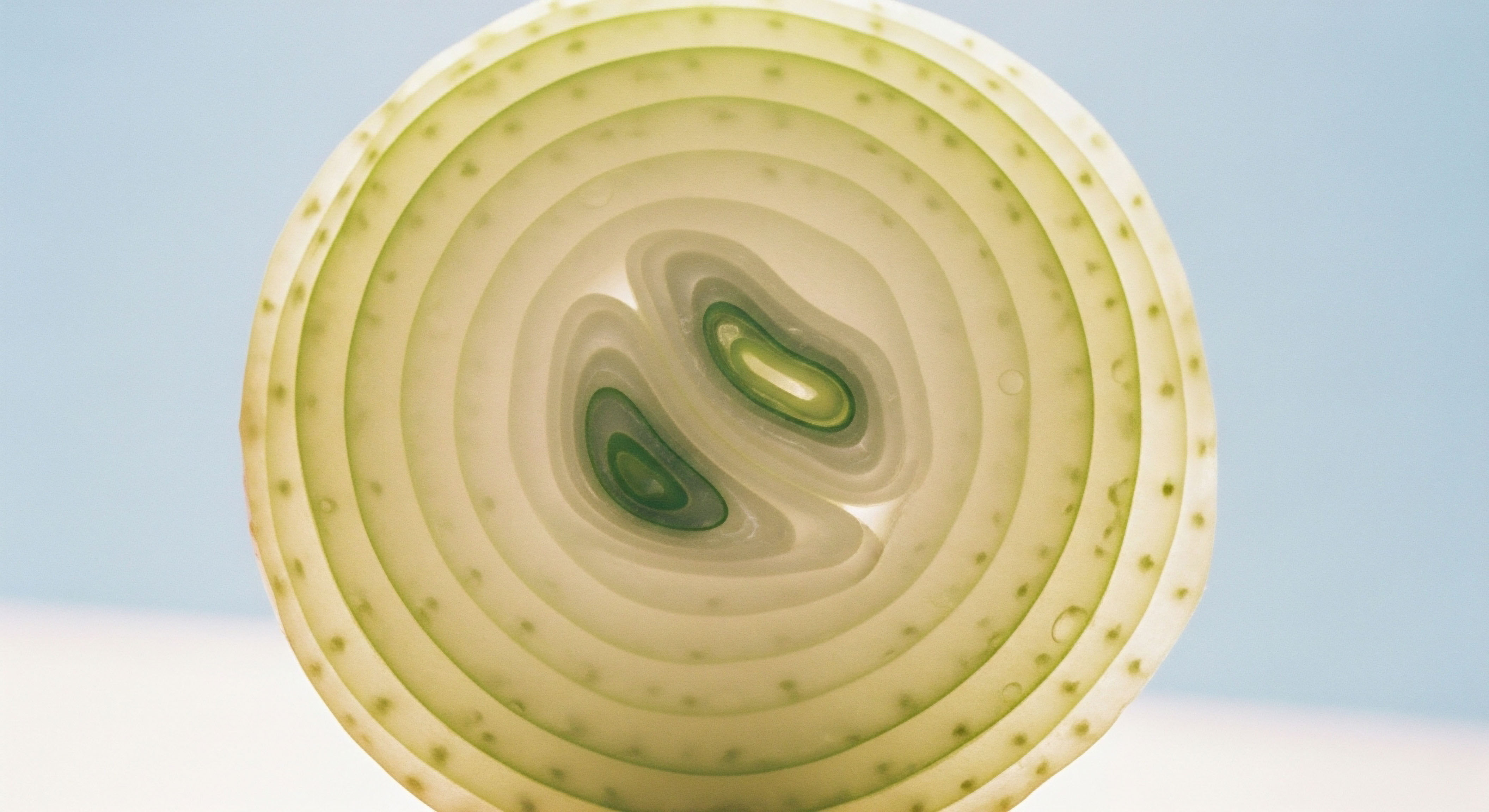

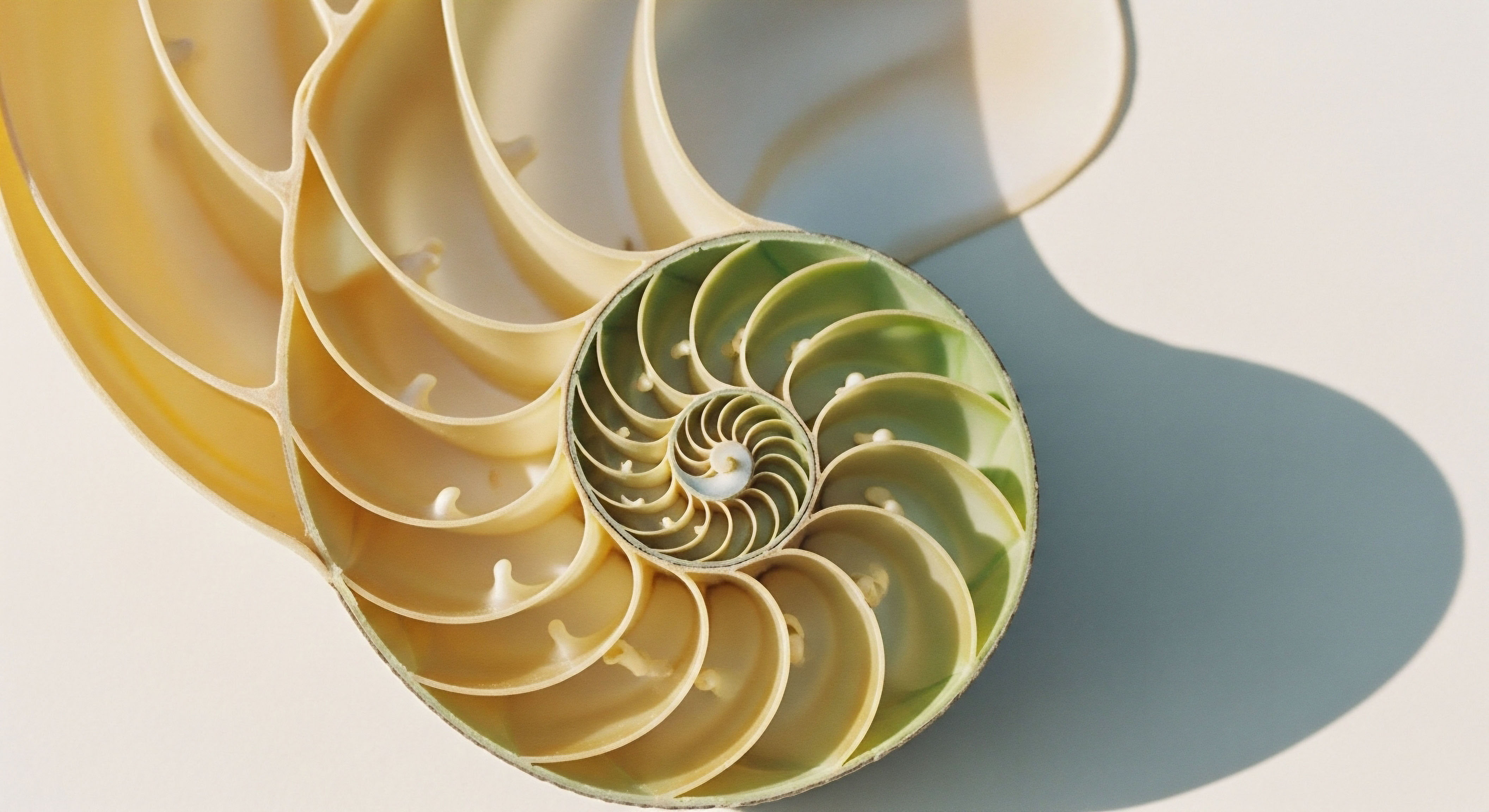

The information you entrust to a wellness program is more than a series of numbers; it is a direct reflection of your internal biological world. When you log your sleep patterns, track your heart rate variability, or note your daily nutrition, you are creating a digital extension of your own physiology.

This data, in its rawest form, maps the intricate functions of your endocrine system, the efficiency of your metabolic processes, and the daily rhythms that define your state of well-being. The central question, then, is what happens to this deeply personal chronicle of your health when it is collected, aggregated, and supposedly made anonymous. The answer begins with understanding the nature of this information and the language used to describe its handling.

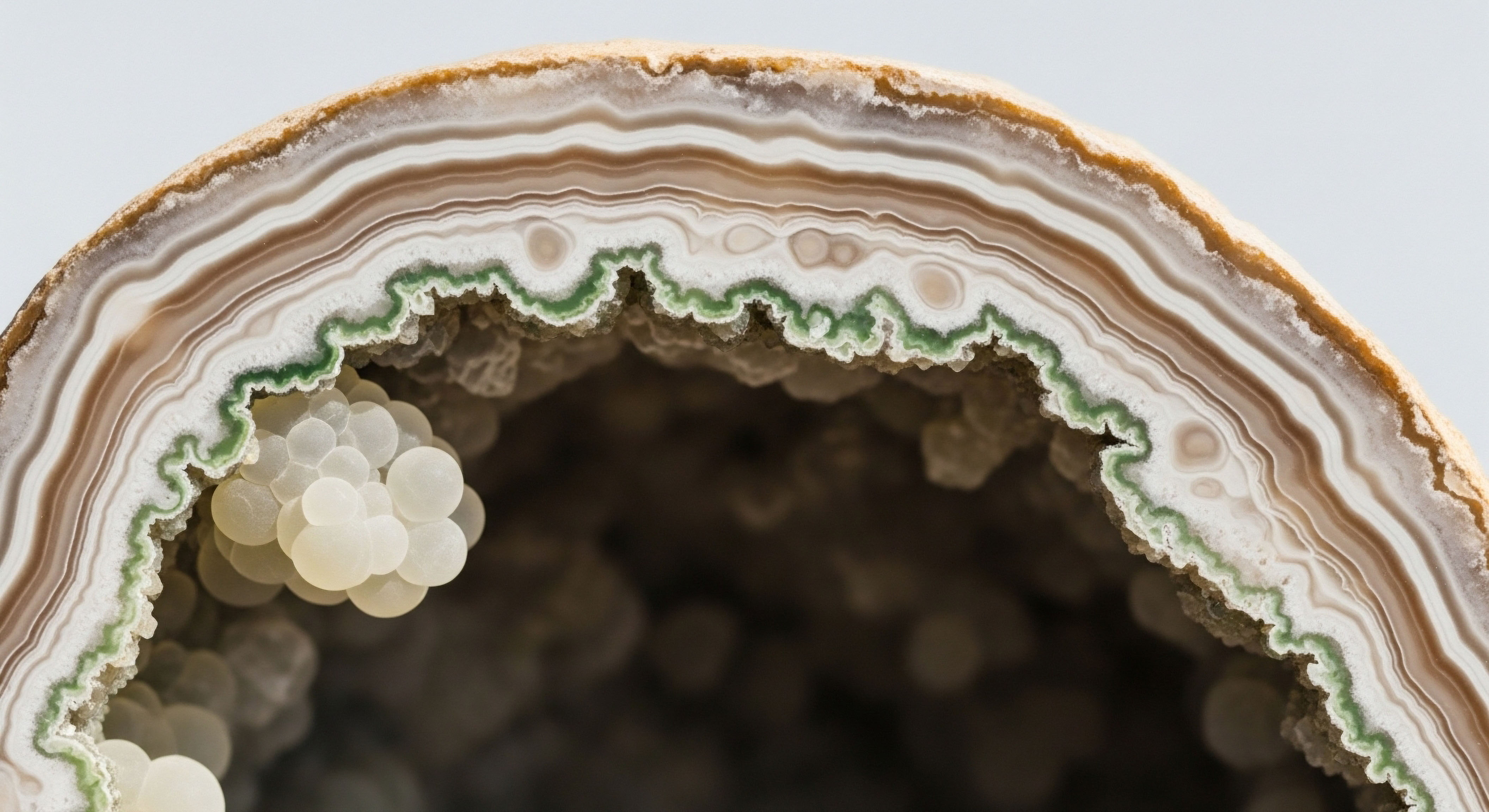

In the world of data privacy, a critical distinction is made between Personally Identifiable Information (PII) and what is often termed “anonymized” or “de-identified” data. PII includes direct identifiers, the things that point unambiguously to you, such as your name, social security number, or address.

The process of de-identification strips this top layer of information away, leaving behind the core clinical and behavioral data. This includes your biometric markers like blood pressure and cholesterol levels, your history of medication use, and even your daily activity levels.

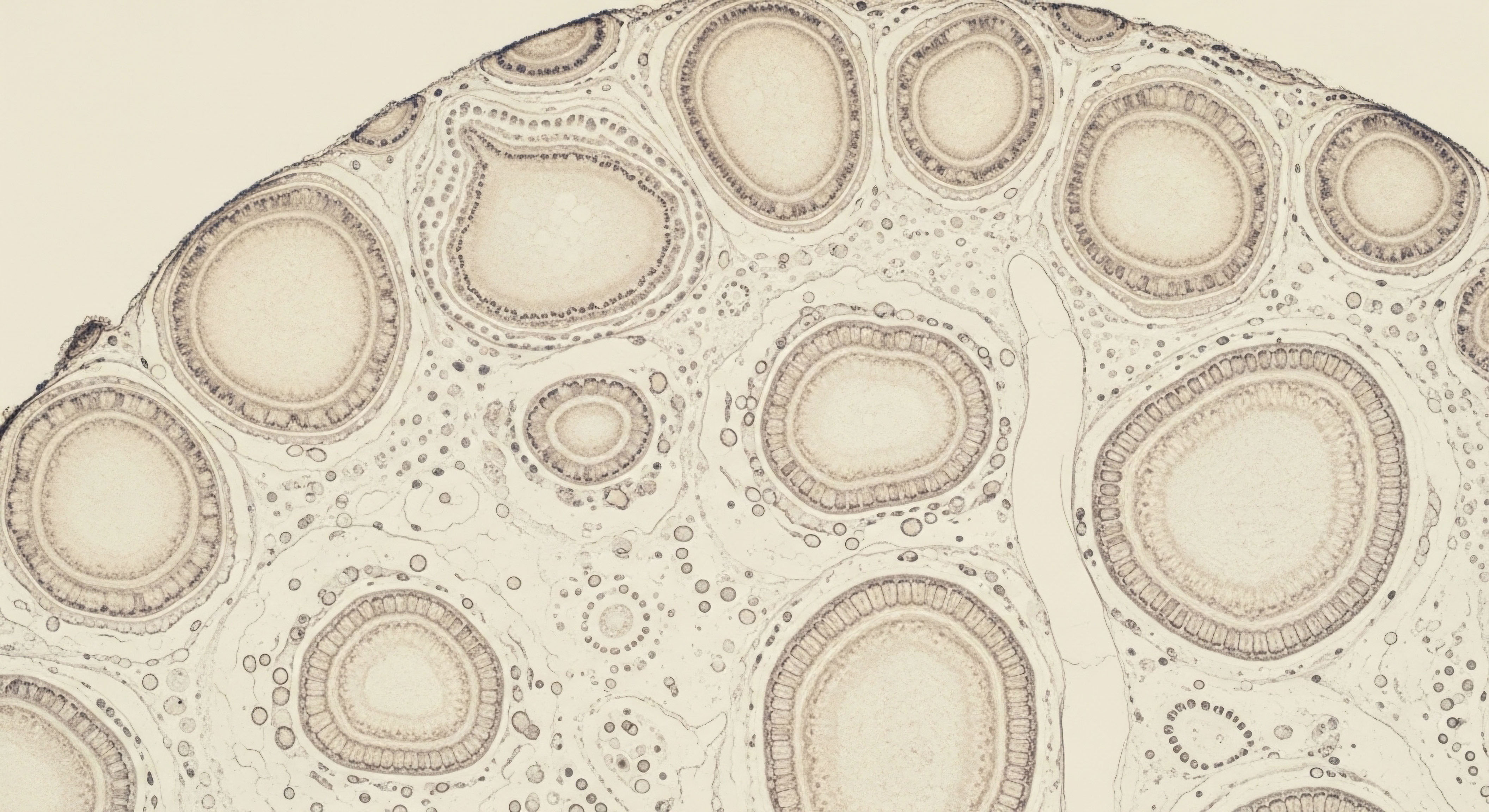

The intention is to create a dataset that can be used for broad analysis without compromising the identity of any single individual. Your personal health record becomes a single data point among thousands, contributing to a larger picture of a population’s health.

De-identified health information represents a detailed map of your body’s internal functions, just without your name written at the top.

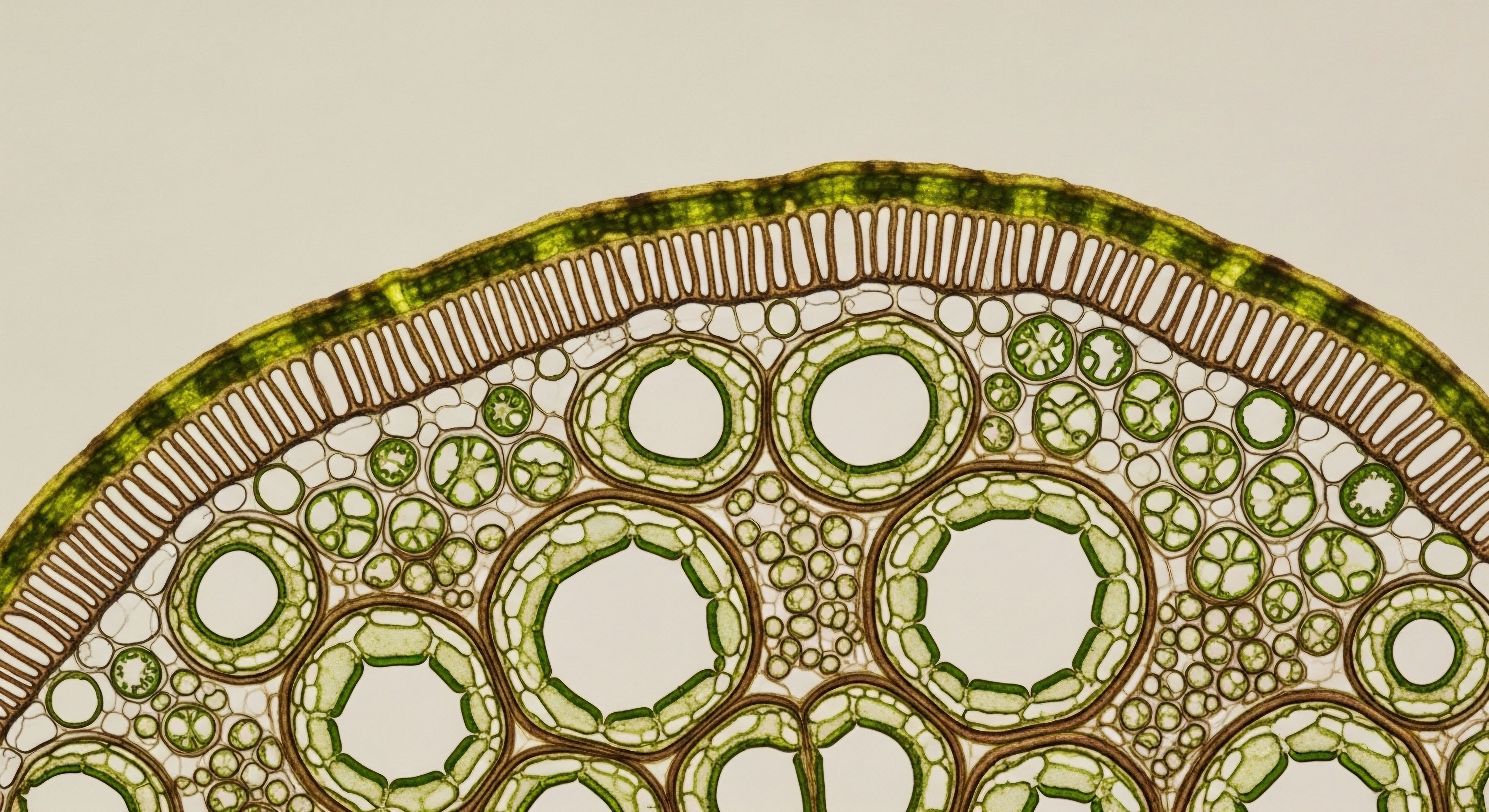

This process, however, introduces a profound vulnerability. Your biological and behavioral data signature is exceptionally unique. Consider the combination of your age, your zip code, the time you typically exercise, and your specific resting heart rate. While each piece of information seems generic on its own, their combination creates a specific fingerprint.

Researchers have demonstrated that by cross-referencing these supposedly anonymous health datasets with other publicly or commercially available information, such as voter registration lists or credit card records, it is possible to re-associate a specific identity with its corresponding health profile. The very uniqueness that defines your personal health journey also makes your data a target for re-identification.

What Is De-Identified Data Really?

De-identified data is health information that has had common identifiers removed. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) specifies two primary methods for achieving this status. The first is the “Safe Harbor” method, which involves the removal of a specific list of 18 identifiers.

The second is “Expert Determination,” where a statistical expert verifies that the risk of re-identification is very small. Many wellness programs that collect health data operate under the premise that by adhering to these standards, they are protecting user privacy.

These programs can then share or sell this aggregated, de-identified data to third parties, including employers, marketers, and researchers, often without your explicit ongoing consent for each use. This sharing is frequently justified as a way to improve the program, conduct research, or provide your employer with a high-level overview of the workforce’s health.

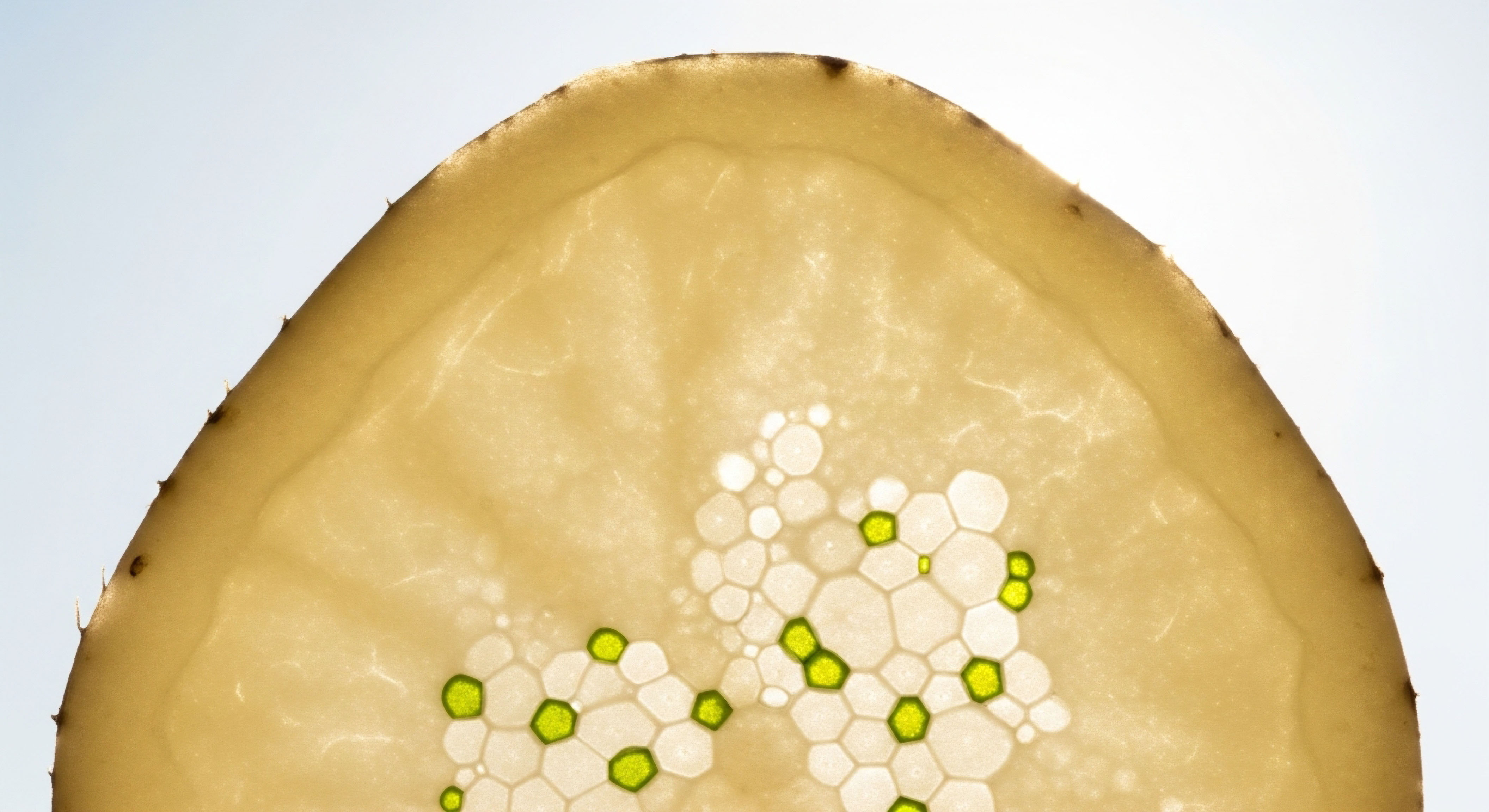

The physiological data collected is a direct window into your body’s most sensitive operations. For a man undergoing Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), this data could include testosterone levels, estrogen levels, and the use of medications like Anastrozole or Gonadorelin.

For a woman tracking her cycles for fertility or managing perimenopausal symptoms, this could involve data on progesterone levels or the use of low-dose testosterone. For an individual using growth hormone peptides like Ipamorelin to enhance recovery, the data reflects a sophisticated and personalized health protocol.

When this information is de-identified, the clinical details remain. The dataset still contains the biological markers of a 45-year-old male on a specific TRT protocol or a 50-year-old female using subcutaneous testosterone. It is the story of your body, told in the language of biochemistry, waiting to be read.

Intermediate

The journey of your health data from personal input to an anonymized dataset is a technical process with significant implications for your privacy. Understanding this process illuminates the specific points of vulnerability. When you participate in a corporate wellness program, whether through a wearable device, a health risk assessment survey, or biometric screening, you are generating a stream of information.

This data is transmitted and stored, often in cloud-based systems that may have varying levels of security. The initial step of de-identification involves scrubbing the data of those 18 specific identifiers outlined by HIPAA’s Safe Harbor provision. This is an algorithmic process, a digital redaction of your name, birth date, and other direct links to your identity.

The resulting dataset, however, is far from truly anonymous. Its utility and value to data brokers and researchers lie in its specificity. An aggregated report for an employer might show that a certain percentage of the workforce has high blood pressure or is at risk for diabetes.

A research institution might purchase the data to study the effects of a particular lifestyle intervention. In each case, the granularity of the data is what makes it useful. This granularity is also what makes it fragile from a privacy standpoint. The modern data ecosystem is vast and interconnected.

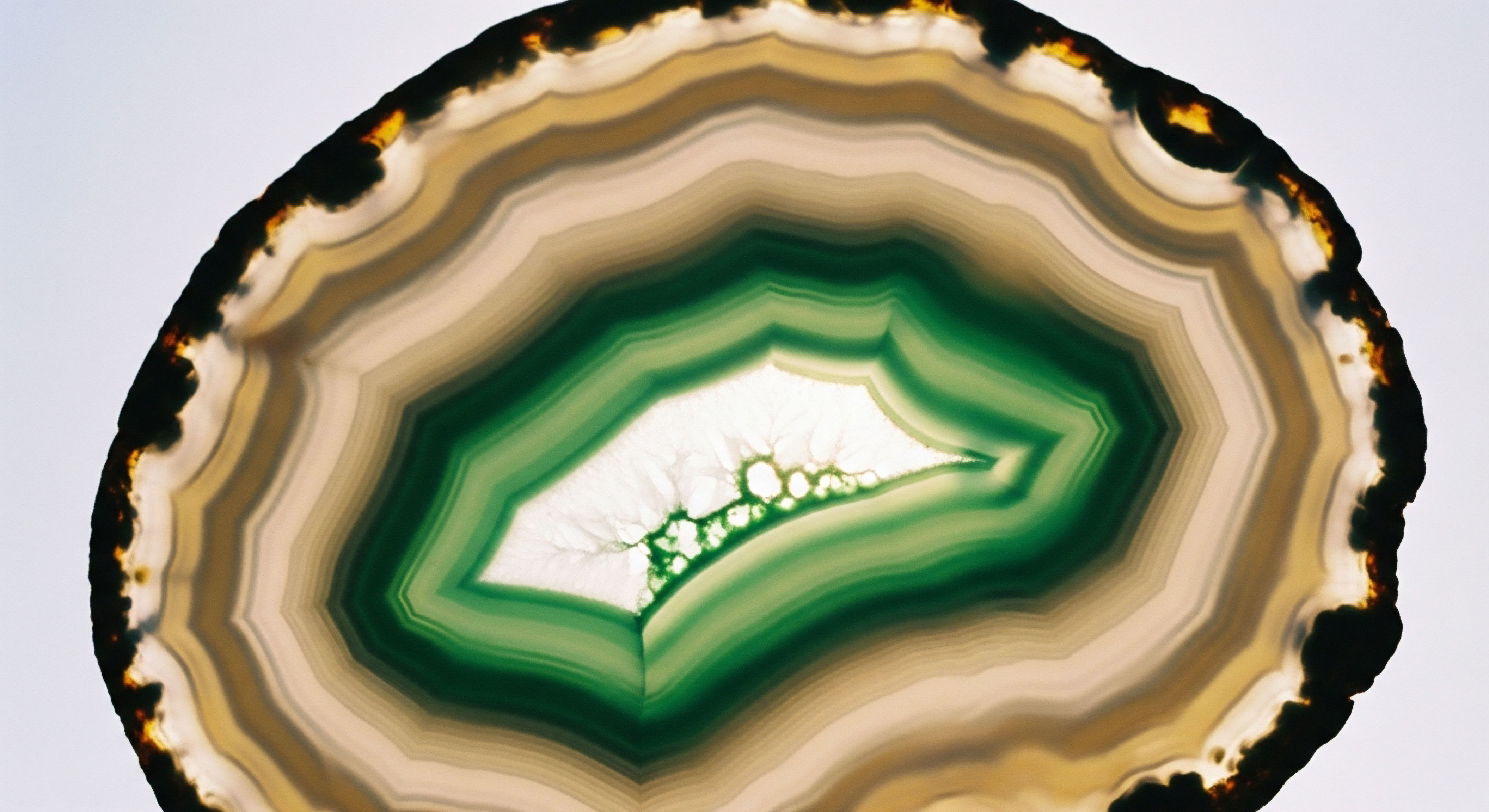

Your de-identified wellness data is one puzzle piece. Other pieces exist in different databases ∞ your consumer purchasing habits, your social media activity, your public records. The act of re-identification is the process of finding enough overlapping pieces to put the puzzle back together, linking a name to a supposedly anonymous health profile.

How Does Re-Identification Actually Work?

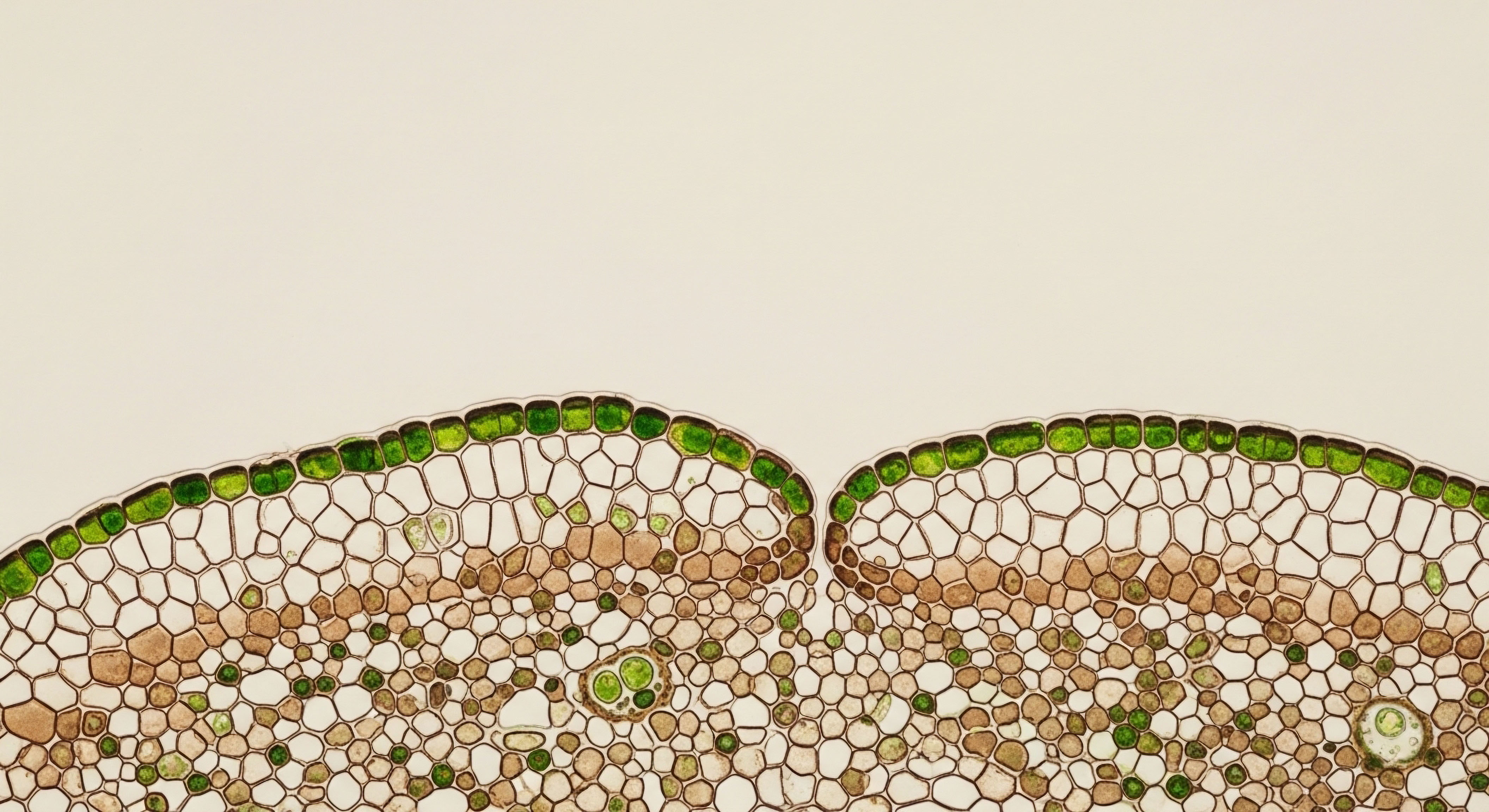

The mechanics of re-identification can be understood through an analogy. Imagine your health profile as a detailed, deeply personal story written on a piece of paper, but with your name blacked out. If someone only has that single piece of paper, it may be difficult to know who wrote it.

Now, imagine that person also has access to a library of other documents. They find a travel log detailing trips to a specific city, a credit card statement showing a gym membership, and a public record of home ownership in a particular neighborhood.

By comparing the unique details across these separate documents, they can deduce with high certainty the author of the original story. In the digital world, data brokers and analytics companies perform this same function at a massive scale, using sophisticated algorithms to cross-reference datasets. They can correlate the location data from your fitness tracker’s mobile app with your known home address or workplace, effectively stripping away the layer of anonymity.

Re-identification is the process of reassembling a person’s identity by finding the unique overlaps between their ‘anonymous’ health data and other available information.

The types of data collected by wellness programs vary in their sensitivity and potential for re-identification. Understanding these categories helps clarify the specific risks involved.

| Data Category | Examples | Primary Privacy Concern |

|---|---|---|

| Biometric Data | Blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose levels, body mass index (BMI), testosterone levels. |

This data provides a direct snapshot of your physiological state. Re-identification could expose specific health conditions or predispositions, potentially leading to discrimination in areas like life insurance or credit applications. |

| Behavioral & Lifestyle Data | Step counts, sleep patterns, dietary logs from apps, gym attendance, grocery purchases through linked programs. |

This information creates a detailed profile of your daily habits. It can be used for targeted marketing, but also to make inferences about your discipline, health consciousness, and even emotional state, which could be used in non-health contexts. |

| Genetic Information | Data from direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic tests integrated with wellness programs. |

Your genetic code is the ultimate unique identifier. While protected by laws like the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) in employment, the privacy of this data outside that context is less clear, and its value for research and marketing is immense. |

| Subjective Self-Reported Data | Answers to health risk assessments (HRAs) about mood, stress levels, alcohol consumption, or sexual health (e.g. using PT-141). |

This is some of the most sensitive personal information. Its exposure could lead to significant personal and professional embarrassment or stigma. Wellness apps tracking menstrual cycles, for instance, could reveal information about pregnancy or fertility challenges. |

What Questions Should You Ask about Your Wellness Program?

Given these vulnerabilities, approaching any wellness program with a critical and informed perspective is a form of proactive self-care. Your health data is an asset, and you have the right to understand how it is being managed, protected, and used. Engaging with the program’s privacy policy and terms of service is essential. Here are some critical questions to consider:

- Data Collection ∞ What specific data points are being collected? Is the collection limited to what is necessary for the program, or is it broader?

- Data Sharing ∞ With whom is my de-identified data being shared? Is there a clear list of third parties, or is the language vague? Can I opt out of this sharing?

- Data Security ∞ What specific security measures, such as encryption, are used to protect my data both in transit and at rest?

- Re-Identification Policy ∞ Does the privacy policy explicitly prohibit attempts to re-identify my data?

- Data Retention ∞ How long is my data stored, and what is the process for its deletion if I leave the program or the company?

- Voluntariness ∞ Is participation truly voluntary? Are there financial penalties for non-participation or for failing to meet certain health targets, which could be seen as coercive?

The answers to these questions provide a clearer picture of the pact you are making. A program that is transparent about its data practices, employs robust security, and prioritizes user consent fosters a culture of trust. A program with vague policies, extensive data sharing permissions, and financial pressures for participation warrants a higher degree of caution.

Your personal health journey, including any advanced protocols like peptide therapy or hormonal optimization, is built on a foundation of precise, sensitive information. Protecting the privacy of that information is integral to the integrity of the journey itself.

Academic

The assertion that de-identified health data can be kept truly private within the context of corporate wellness programs is a premise that faces significant challenges from both a technical and a legal standpoint. The foundational regulatory framework in the United States, HIPAA, provides a definition of de-identification that is increasingly insufficient in the era of computational data analysis and interconnected digital ecosystems.

The “Safe Harbor” method, which prescribes the removal of 18 specific identifiers, was conceived in a different technological age. It operates on the principle that the absence of these explicit identifiers renders data anonymous. Modern data science, however, demonstrates that identity is not solely contained within these 18 fields. A person’s identity can be inferred with alarming accuracy from the remaining “safe” data points when they are treated as a multidimensional signature.

This leads to the core technical vulnerability ∞ the high dimensionality of health data. A dataset containing hundreds of variables per individual ∞ from lab values and genomic markers to minute-by-minute heart rate and GPS-tagged activity logs ∞ creates a signature so unique that it acts as a functional identifier.

Research in data privacy has repeatedly shown that even a few data points from a supposedly anonymized set can be sufficient for re-identification. For example, a study famously demonstrated that the combination of a 5-digit ZIP code, gender, and full date of birth could uniquely identify a significant percentage of the U.S.

population. Wellness programs collect far more data than this, creating profiles that are orders of magnitude more unique and, therefore, more vulnerable. The privacy risk is a direct function of the data’s richness.

The Inadequacy of Current Legal and Regulatory Frameworks

From a legal perspective, a significant gap exists where the oversight of HIPAA ends and the largely unregulated world of wellness vendors begins. HIPAA’s Privacy Rule applies to “covered entities” (healthcare providers, health plans, and healthcare clearinghouses) and their “business associates.” While a wellness program offered as part of an employer’s group health plan may fall under HIPAA, many standalone programs offered by third-party vendors do not.

These vendors operate in a legal gray area, governed by a patchwork of consumer protection laws and their own privacy policies. These policies are often written in broad language, granting the vendor extensive rights to use, share, and profit from the de-identified data they collect. This creates a situation where an individual’s sensitive health information, once stripped of its primary identifiers, loses much of its legal protection and can be commercialized in ways the individual never intended.

The legal frameworks protecting health data were not designed for a world where ‘anonymous’ information is a valuable, and vulnerable, commercial asset.

Furthermore, the concept of “consent” in this context is often problematic. Employees may be presented with a lengthy, complex privacy policy and a binary choice ∞ agree to the terms and participate in the program (often with financial incentives), or decline and potentially face higher insurance premiums or miss out on benefits.

This raises questions about the voluntariness of such consent. The vacating of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s (EEOC) wellness rules in 2019 created further ambiguity regarding the permissible scope of these programs and the degree to which employers can incentivize the disclosure of sensitive health information without it becoming coercive.

What Is the True Value of This Data?

The economic driver behind the collection of this data is its value to a wide range of third parties. For employers, aggregated data can inform strategies to lower healthcare costs. For marketers, it allows for hyper-targeted advertising of health-related products. For data brokers, it is a raw commodity to be packaged and sold.

For financial institutions, this data holds the potential for a new form of risk assessment. There is a documented concern among privacy advocates that re-identified health data could be used to influence decisions about credit, mortgages, and insurance. An individual whose data suggests a sedentary lifestyle or a predisposition to chronic illness could be algorithmically classified as a higher financial risk. This represents a form of data-driven discrimination based on one’s own biology.

The table below contrasts the stated purpose of data collection in wellness programs with the potential downstream uses of that same data, illustrating the divergence between participant expectations and market realities.

| Stated Purpose (Benefit to Participant) | Potential Downstream Use (Benefit to Third Party) | Governing Framework |

|---|---|---|

|

To improve employee health and well-being through personalized feedback and coaching. |

Sale of aggregated data to employers to assess workforce health risks and productivity. |

Often governed by the vendor’s privacy policy and specific contract with the employer. |

|

To contribute to scientific research for the public good. |

Sale of data to pharmaceutical and life science companies for market research and drug development. |

Can fall outside HIPAA; dependent on the terms of service and research ethics protocols. |

|

To create a supportive community and gamify healthy habits. |

Use of behavioral and location data by marketers for targeted advertising of consumer goods and services. |

Primarily consumer data laws, which offer less protection than health-specific regulations. |

|

To provide discounts on insurance premiums or other financial rewards. |

Potential use by data brokers to create detailed consumer profiles sold to financial institutions for credit and insurance risk modeling. |

A largely unregulated space with significant potential for discriminatory application. |

Ultimately, the challenge of keeping anonymized health data private is a systems-level problem. It exists at the intersection of technology, law, and economics. The technical methods for true anonymization, such as differential privacy, are computationally intensive and not widely adopted. The legal frameworks are porous and have not kept pace with the capabilities of data science.

The economic incentives to collect and monetize this data are immense. From a systems-biology perspective, an individual’s health is an emergent property of countless interconnected biological processes. Similarly, an individual’s digital identity is an emergent property of countless interconnected data points. Protecting health in the 21st century requires a new understanding of privacy that recognizes the intimate, inextricable link between our physical bodies and our digital footprints.

References

- Kaiser Health News. “Workplace Wellness Programs Put Employee Privacy At Risk.” 30 Sept. 2015.

- Society for Human Resource Management. “Wellness Programs Raise Privacy Concerns over Health Data.” 6 Apr. 2016.

- Vorecol. “What role does data privacy play in health and wellness monitoring systems?” 28 Aug. 2024.

- VerSprite. “Data Privacy Tips ∞ Wellness Industry.” 23 Sept. 2019.

- Majumder, M. A. et al. “A Qualitative Study to Develop a Privacy and Nondiscrimination Best Practice Framework for Personalized Wellness Programs.” Journal of Personalized Medicine, vol. 10, no. 4, 2020, p. 235.

Reflection

Your Biology Your Data

The information you have gathered here provides a clinical and technical map of the landscape of data privacy in wellness. This knowledge is the first, essential step. The next step is one of personal reflection. Look at the health data you generate each day ∞ the rhythm of your heart, the quality of your sleep, the subtle shifts in your biochemistry.

This is the language of your body. It is the most personal text you will ever produce. Before you entrust this text to any platform, any program, or any device, the critical act is to pause and consider the terms of that trust.

Your wellness journey is a deeply personal one, a dialogue between you and your own physiology. The decision of who else is allowed to listen in on that conversation is yours alone. True empowerment on this path comes from making that decision with clarity and intention, ensuring that the tools you use to reclaim your vitality do not compromise the integrity of your personal biological narrative.

Glossary

wellness program

data privacy

re-identification

de-identified data

health information

wellness programs

health data

health risk assessment

data brokers

genetic information nondiscrimination act

privacy policy

corporate wellness programs