Fundamentals

You feel it in your body. A persistent fatigue that sleep does not touch, a frustration with weight that defies conventional diet and exercise, or a mental fog that clouds your focus. You follow the guidance of your employer’s wellness program, tracking your steps and calories, yet the numbers on the biometric screening Meaning ∞ Biometric screening is a standardized health assessment that quantifies specific physiological measurements and physical attributes to evaluate an individual’s current health status and identify potential risks for chronic diseases. fail to reflect your effort.

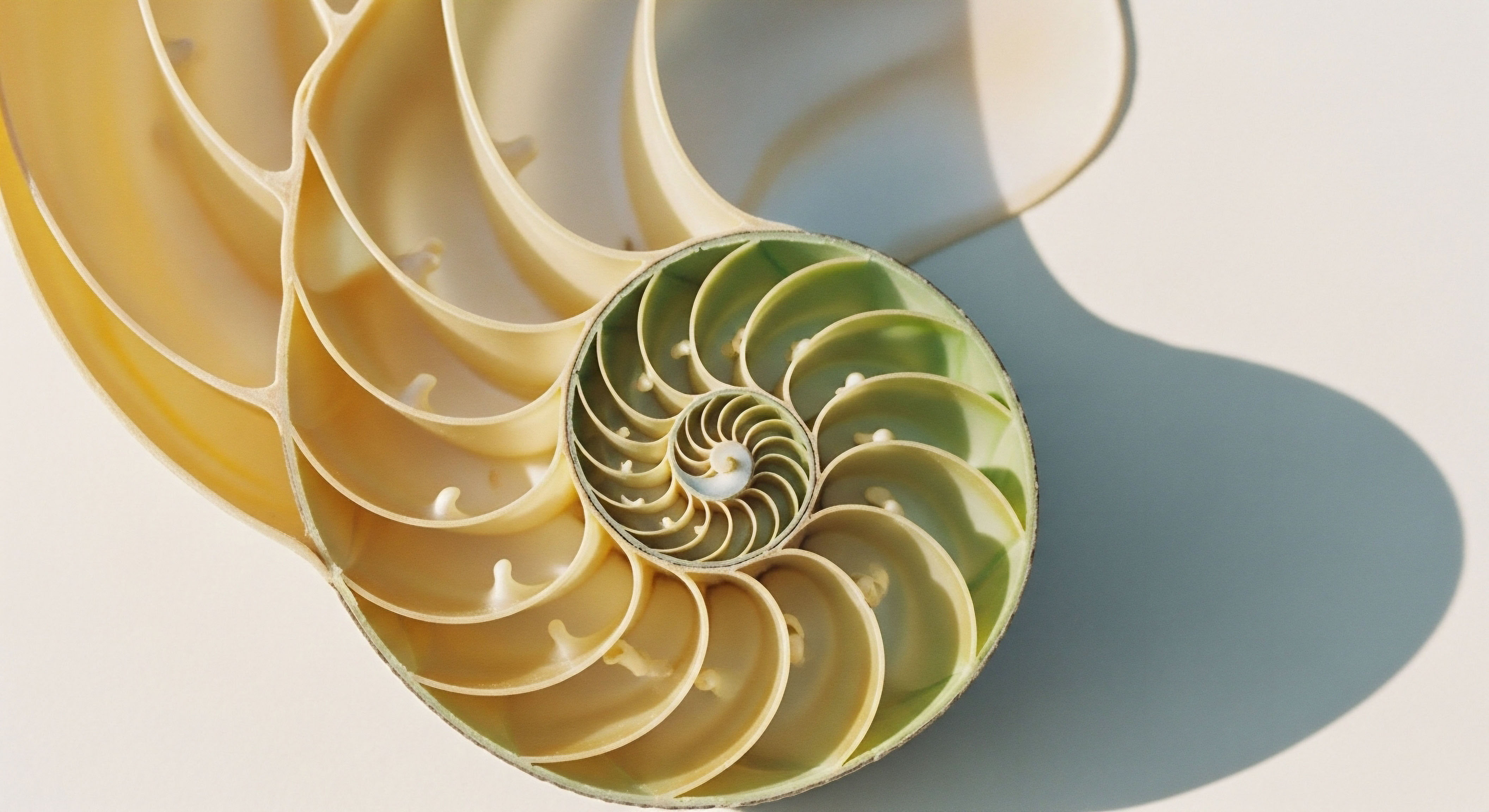

This experience, this disconnect between your dedicated actions and the expected results, is a deeply personal and often isolating one. It is a signal from your body that a generic approach to health is insufficient. Your biology is unique, a complex and elegant system governed by a precise internal messaging service ∞ your endocrine system.

This network of glands and hormones dictates everything from your metabolism and mood to your sleep cycles and stress response. When a corporate wellness initiative applies a single set of standards to a diverse workforce, it fundamentally misunderstands this biological individuality. The very premise of such a program can create a conflict with the core protections of the Americans with Disabilities Act Meaning ∞ The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), enacted in 1990, is a comprehensive civil rights law prohibiting discrimination against individuals with disabilities across public life. (ADA).

The ADA’s purpose is to prevent discrimination based on disability. A core component of this protection is the strict limitation on an employer’s ability to require medical examinations or make inquiries about an employee’s health. These actions are permitted only under specific, job-related circumstances.

A wellness program that An outcome-based program calibrates your unique biology, while an activity-only program simply counts your movements. requires employees to undergo biometric screenings ∞ measuring blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, or body mass index (BMI) ∞ or to complete a detailed Health Risk Assessment Meaning ∞ A Health Risk Assessment is a systematic process employed to identify an individual’s current health status, lifestyle behaviors, and predispositions, subsequently estimating the probability of developing specific chronic diseases or adverse health conditions over a defined period. (HRA) is, by its nature, conducting a medical examination and making health-related inquiries. The central question then becomes one of voluntariness. The law allows for such examinations if they are part of a “voluntary” employee health program.

The concept of “voluntary” is where the lived experience of an employee and the legal framework intersect. Participation is voluntary when an employee can freely choose to take part or to abstain without facing negative consequences. An employer cannot require participation, deny health coverage, or take any adverse action against an employee who chooses not to participate.

This includes retaliation, intimidation, or coercion. When a program offers a substantial financial reward for participation or imposes a significant penalty for non-participation, the line between encouragement and coercion Meaning ∞ Coercion, within a clinical framework, denotes the application of undue pressure or external influence upon an individual, compelling a specific action or decision, particularly regarding their health choices or physiological management. becomes blurred. A large incentive can transform a choice into a necessity for many employees, making the disclosure of protected health information feel compulsory. This pressure is what brings a seemingly optional program under the scrutiny of the ADA.

A wellness program that mandates biometric screening as a condition for a reward functions as a medical examination under the ADA.

Furthermore, for a wellness program Meaning ∞ A Wellness Program represents a structured, proactive intervention designed to support individuals in achieving and maintaining optimal physiological and psychological health states. to be permissible under the ADA, it must be “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease.” This means the program cannot be a subterfuge for discrimination or overly burdensome. A program is considered reasonably designed Meaning ∞ Reasonably designed refers to a therapeutic approach or biological system structured to achieve a specific physiological outcome with minimal disruption. if its purpose is to alert employees to potential health risks.

However, this definition becomes complicated when the program’s metrics and goals fail to account for the vast spectrum of human physiology. For an individual with a thyroid condition, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), or age-related hormonal shifts, standardized targets for BMI or cholesterol may be clinically inappropriate or even impossible to achieve through the program’s prescribed methods.

In these instances, the program’s design ceases to be a tool for health promotion and instead becomes a mechanism that could penalize an individual for the manifestation of their underlying medical condition, placing it in direct opposition to the spirit and letter of the law.

The interaction between these programs and other nondiscrimination laws, such as the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), adds another layer of complexity. GINA Meaning ∞ GINA stands for the Global Initiative for Asthma, an internationally recognized, evidence-based strategy document developed to guide healthcare professionals in the optimal management and prevention of asthma. prohibits discrimination based on genetic information, which includes family medical history. When an HRA, even one within a wellness program, asks for this information, it enters a protected domain.

While GINA allows for the collection of this data if it is knowing, written, and voluntary, the presence of an incentive tied to completing the HRA can again raise questions of coercion. An employee should be able to receive an incentive without being compelled to disclose their genetic information.

The architecture of a wellness program must be sophisticated enough to navigate these distinct legal requirements, ensuring that an initiative designed to support health does not inadvertently violate the fundamental rights it is obligated to protect.

Intermediate

The architecture of many corporate wellness programs Meaning ∞ Wellness programs are structured, proactive interventions designed to optimize an individual’s physiological function and mitigate the risk of chronic conditions by addressing modifiable lifestyle determinants of health. rests on a foundation of standardized metrics. Goals are often set for Body Mass Index (BMI), blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and blood glucose. From a public health perspective, these markers provide a broad overview of risk factors within a population.

From the perspective of an individual’s endocrine system, these numbers are merely data points, outcomes of a deeply complex and interconnected biological conversation. When a wellness program is not designed with an understanding of this conversation, its well-intentioned goals can become instruments of inequity, creating scenarios where an employee is penalized for their unique physiology.

This is the functional translation of a potential ADA violation ∞ the program’s structure fails to provide reasonable accommodations for individuals whose disabilities directly affect the very biomarkers being measured.

The ADA requires employers to provide reasonable accommodations, which are modifications or adjustments that enable an employee with a disability to participate in workplace activities, including wellness programs. Consider an employee with hypothyroidism, a condition where the thyroid gland does not produce enough thyroid hormone.

This hormonal insufficiency directly impacts metabolism, often leading to weight gain, elevated cholesterol, and fatigue. A wellness program that uses BMI as a primary success metric and offers a significant financial incentive for achieving a target below 25 creates a substantial barrier for this employee. Their medical condition makes the program’s goal exceptionally difficult to attain.

To be compliant with the ADA, the program would need to offer a reasonable alternative, such as allowing the employee to earn the incentive by working with their endocrinologist on a personalized care plan or by demonstrating engagement in activities that are medically appropriate for their condition, regardless of the outcome on the scale.

How Can a Program Be Both Optional and Coercive?

The concept of coercion under the ADA is a central issue in the debate over wellness programs. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Your employer is legally prohibited from using confidential information from a wellness program to make employment decisions. (EEOC), the agency responsible for enforcing the ADA, has long grappled with defining the point at which an incentive becomes coercive.

If an incentive is so large that an employee feels they have no real choice but to participate and disclose their medical information, the program’s voluntary nature is undermined. The EEOC Meaning ∞ The Erythrocyte Energy Optimization Complex, or EEOC, represents a crucial cellular system within red blood cells, dedicated to maintaining optimal energy homeostasis. has proposed rules over the years attempting to set clear limits, at times suggesting that incentives should be “de minimis,” like a water bottle or a small gift card, to avoid this coercive effect.

In other instances, regulations have permitted incentives up to 30% of the total cost of self-only health insurance coverage. This shifting regulatory landscape highlights the inherent tension between two goals ∞ encouraging healthy behaviors and protecting employees from being forced to reveal personal health data.

This tension is most apparent when an employee must choose between forgoing a substantial financial reward (or paying a significant penalty) and participating in a program that is ill-suited to their health status. Imagine a perimenopausal woman experiencing fluctuations in cortisol and estrogen.

These hormonal shifts can lead to insulin resistance, sleep disturbances, and changes in body composition. A wellness program promoting high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and a low-calorie diet might be metabolically stressful and counterproductive for her. The pressure to participate, driven by a financial incentive, could lead her to engage in activities that exacerbate her symptoms.

In this context, the “optional” program effectively coerces her into a health protocol that is medically inadvisable for her specific endocrine state, creating a clear potential for an ADA violation.

A program’s failure to offer medically appropriate alternatives for individuals with disabilities is a failure to provide reasonable accommodation.

To better illustrate this conflict, the following table contrasts standard wellness program metrics with a more clinically nuanced, personalized approach that respects biological individuality.

| Standard Wellness Metric | Personalized Endocrine-Aware Alternative | Relevant Clinical Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Body Mass Index (BMI) < 25 |

Focus on waist-to-hip ratio, body composition analysis (e.g. DEXA scan), and tracking inflammatory markers like hs-CRP. The goal is metabolic health, not a specific weight. |

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), Hypothyroidism, Cushing’s Syndrome, Insulin Resistance. |

| Total Cholesterol < 200 mg/dL |

Analyze advanced lipid panels (LDL particle number, ApoB, Lp(a)), and focus on the triglyceride-to-HDL ratio as a primary indicator of cardiovascular risk. |

Familial Hypercholesterolemia, Hypothyroidism, Menopause. |

| Participation in High-Intensity Step Challenge |

Provide credit for consistent, medically appropriate movement, such as restorative yoga, swimming, or strength training, based on consultation with a healthcare provider. |

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Adrenal Dysfunction (HPA Axis Dysregulation), Autoimmune Conditions (e.g. Rheumatoid Arthritis). |

| Achieving 8 Hours of Sleep Per Night |

Track sleep quality through wearables (e.g. REM/deep sleep duration) and provide resources for improving sleep hygiene, acknowledging that hormonal shifts can disrupt sleep architecture. |

Perimenopause/Menopause (hot flashes), Low Testosterone (in men), Sleep Apnea. |

Ultimately, a wellness program’s compliance with the ADA hinges on its flexibility and its recognition that health is not a one-size-fits-all proposition. The program must be “reasonably designed,” which implies a design that is reasonable for all participants, including those with disabilities.

This requires a shift from outcome-based incentives (e.g. achieving a certain biomarker) to participation-based incentives that allow for personalization. An employee should be able to earn the full reward by demonstrating that they are actively engaged in a health plan that is safe and effective for them, even if their biomarkers do not align with the program’s generic targets.

Without this flexibility, the program risks becoming a discriminatory barrier, punishing employees for the very health conditions the ADA was enacted to protect.

Academic

The intersection of corporate wellness programs and the Americans with Disabilities The ADA requires health-contingent wellness programs to be voluntary and reasonably designed, protecting employees with metabolic conditions. Act (ADA) represents a complex legal and bioethical nexus, where statutory language confronts the irreducible complexity of human physiology. The core of the issue resides in the interpretation of two key ADA provisions ∞ the prohibition against non-job-related medical examinations and inquiries (42 U.S.C.

§ 12112(d)(4)(A)), and the safe harbor provision for “bona fide benefit plans” (§ 12201(c)). The legal discourse surrounding these programs, particularly the definition of “voluntary,” has been the subject of extensive litigation and fluctuating regulatory guidance from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Your employer is legally prohibited from using confidential information from a wellness program to make employment decisions. (EEOC).

An academic analysis reveals that a program’s potential for ADA violation emerges when its design principles are misaligned with the biological realities of endocrine and metabolic function, effectively transforming a health-promotion tool into a mechanism of medical scrutiny and potential discrimination.

The legal history is instructive. Cases such as EEOC v. Flambeau, Inc. and EEOC v. Honeywell International, Inc. illustrate the judicial struggle to balance employer interests in promoting health and reducing healthcare costs with the ADA’s mandate to protect employee privacy and prevent disability-based discrimination.

In Flambeau, the court found that a wellness program requiring biometric screening was permissible under the ADA’s safe harbor for insurance benefit plans. Conversely, the EEOC has consistently argued that a large financial penalty for non-participation renders a program involuntary, thus violating the ADA, a position it took in its lawsuit against Honeywell.

The Honeywell program imposed significant surcharges on employees who declined biometric screening, which the EEOC contended was coercive. This legal friction demonstrates the absence of a settled consensus on the degree of financial inducement that transforms a voluntary choice into an economic mandate.

What Does ‘reasonably Designed’ Mean in the Context of the HPA Axis?

The ADA permits wellness programs that are “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease.” From a legal standpoint, this has often been interpreted to mean the program is not a subterfuge for discrimination and relies on conventional health metrics.

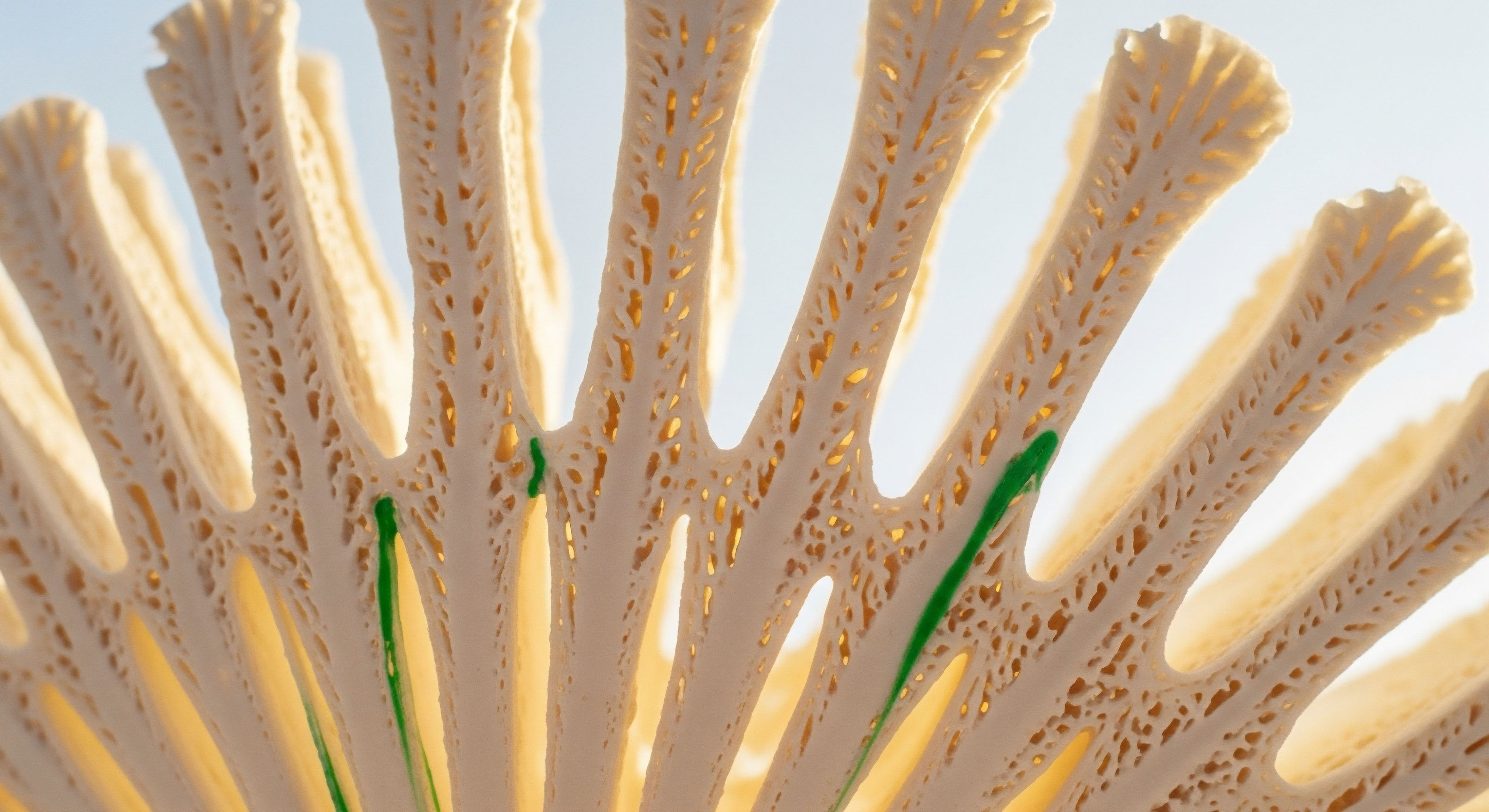

A deeper, more scientifically grounded analysis, however, must interrogate what “reasonably designed” means in the context of neuroendocrine systems like the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis Meaning ∞ The HPA Axis, or Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis, is a fundamental neuroendocrine system orchestrating the body’s adaptive responses to stressors. is the body’s central stress response system. Chronic physical or psychological stress, including the pressure to meet arbitrary wellness targets, can lead to HPA axis dysregulation. This dysregulation has profound metabolic consequences, including elevated cortisol, which promotes visceral adiposity, insulin resistance, and hypertension ∞ the very conditions wellness programs aim to prevent.

A wellness program that applies uniform, high-pressure tactics (e.g. company-wide weight loss competitions, stringent activity goals) without considering an individual’s allostatic load (the cumulative wear and tear on the body from chronic stress) cannot be considered “reasonably designed” from a physiological perspective.

For an employee already experiencing significant life stress, the added pressure of a wellness program can become the tipping point into HPA axis dysfunction. In this scenario, the program is not promoting health; it is contributing to the pathophysiology of metabolic disease.

An ADA-compliant program, therefore, would need a design that incorporates principles of stress modulation and recovery, offering alternatives like mindfulness training, restorative yoga, or flexible work arrangements, and recognizing these as valid, health-promoting activities worthy of incentives. The failure to account for the HPA axis’s role in health is a fundamental design flaw that can have discriminatory effects on individuals susceptible to stress-related conditions, which may themselves be disabilities under the ADA.

A wellness program that ignores the biological impact of stress is not reasonably designed to promote health.

The following table outlines potential contraindications of common wellness program components for specific endocrine and metabolic profiles, highlighting the need for a systems-biology approach to program design.

| Common Wellness Intervention | Potentially Affected Population | Physiological Rationale and Potential for Harm |

|---|---|---|

| Aggressive Caloric Restriction (e.g. 1200 kcal/day) |

Individuals with Hypothyroidism or a history of eating disorders. |

Can suppress thyroid function by down-regulating the conversion of inactive T4 to active T3 hormone. For those with a history of disordered eating, it can trigger relapse. This approach fails to account for individual basal metabolic rates and hormonal regulation of appetite. |

| Mandatory High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) |

Individuals with HPA Axis Dysregulation (“Adrenal Fatigue”) or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. |

Excessive intensity can be perceived by the body as a significant stressor, further elevating cortisol in an already dysregulated system. This can worsen fatigue, disrupt sleep, and impair immune function, leading to a net negative health outcome. |

| Low-Fat Diet Promotion |

Perimenopausal and postmenopausal women; men with low testosterone. |

Dietary fat, particularly cholesterol, is a crucial precursor for the synthesis of all steroid hormones, including estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. Severely limiting fat intake can impair the body’s ability to produce these essential hormones, exacerbating symptoms of hormonal imbalance. |

| Outcome-Based Incentives for Glucose Control |

Individuals with Type 1 Diabetes or brittle Type 2 Diabetes. |

The extreme glycemic variability in these conditions can make it nearly impossible to consistently meet a specific HbA1c or fasting glucose target. Penalizing such individuals for this variability is a direct penalty for the manifestation of their disability. |

The Subterfuge Provision and Biological Individuality

The ADA states that the safe harbor provision cannot be used as a “subterfuge to evade the purposes of.” A program, while appearing as a bona fide benefit plan on the surface, could be considered a subterfuge if its practical effect is to discriminate.

A wellness program built on rigid, population-level biometric targets, without meaningful and accessible alternatives for those with disabilities, arguably functions as a subterfuge. It creates a system where employees with “compliant” biologies are rewarded, while those with non-compliant biologies ∞ often due to underlying medical conditions ∞ are penalized. This establishes a two-tiered system of benefits that is fundamentally discriminatory.

For example, an individual with a genetic predisposition to high LDL cholesterol (like Familial Hypercholesterolemia) may never reach a program’s target through diet and exercise alone. They require medical intervention. A program that withholds a significant incentive from this individual because of their unchangeable genetic trait is using a health metric as a proxy for discrimination.

A truly non-subterfuge, reasonably designed program would shift its focus from the biometric outcome to the process. It would reward the employee for adhering to their prescribed medical treatment plan, thereby promoting their actual health without penalizing them for their genetic disability. This approach respects biological individuality Meaning ∞ Biological individuality refers to the distinct physiological and biochemical characteristics differentiating organisms. and aligns with the core purpose of the ADA ∞ to ensure equal opportunity and treatment for all employees, regardless of their health status.

References

- Bagenstos, Samuel R. “The Future of Disability Law.” The Yale Law Journal, vol. 114, no. 1, 2004, pp. 1-84.

- Hempton, Jeff. “EEOC v. Honeywell and the new frontiers of wellness programs.” Employee Relations Law Journal, vol. 42, no. 2, 2016, pp. 62-71.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Questions and Answers about the EEOC’s Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on Employer Wellness Programs.” 20 April 2015.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Americans with Disabilities Act.” Federal Register, vol. 81, no. 95, 17 May 2016, pp. 31126-31158.

- Mello, Michelle M. and Noah A. G. Wertheimer. “The EEOC’s New Rules on Wellness Programs ∞ A Reasonable Compromise?” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 375, no. 2, 2016, pp. 101-103.

- Madison, Kristin M. “The Law and Policy of Employer-Sponsored Wellness Programs ∞ A New Generation.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, vol. 41, no. 4, 2016, pp. 653-698.

- Schmidt, Harald, et al. “Voluntary and Equitable Workplace Wellness Programs.” The Hastings Center Report, vol. 46, no. 1, 2016, pp. 12-15.

- Kyrou, Ioannis, et al. “Stress, Allostasis, and Metabolic Complications.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 39, no. 6, 2018, pp. 843-868.

- Pascoe, M. C. et al. “The impact of stress on students in secondary school and the role of school-based strategies.” Australian Journal of Education, vol. 64, no. 1, 2020, pp. 93-112.

- Nicolaides, Nicolas C. et al. “The HPA Axis, Glucocorticoids and Adipose Tissue Biology.” Metabolism, vol. 64, no. 3, 2015, pp. 342-352.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a framework for understanding the complex interplay between law, corporate policy, and your personal biology. It moves the conversation from a simple question of legal compliance to a deeper consideration of physiological respect. As you process this, the most valuable step is to turn your focus inward.

Consider the signals your own body provides. Think about moments when you have felt aligned with your health and moments of disconnect, when your efforts did not yield the vitality you sought. Where have generic wellness prescriptions succeeded for you, and where have they fallen short?

This knowledge is a tool for self-advocacy. It equips you to look at a wellness program not as a set of rules to be followed, but as a resource to be evaluated. Does its design honor the concept of biological individuality?

Does it offer the flexibility to create a path that supports your unique endocrine and metabolic function? Understanding the science of your own body is the first step. The next is recognizing that a truly beneficial wellness initiative is one that partners with you on your specific health journey, providing support and resources without imposing rigid, and potentially harmful, uniformity.

Your path to sustained well-being is yours to define, informed by data, guided by your body’s wisdom, and protected by principles of equity and respect.