Fundamentals

The moment an envelope from human resources arrives, detailing the annual wellness initiative, a complex internal dialogue often begins. For many, it presents a flicker of opportunity ∞ a structured moment to pause and take inventory of the intricate systems that govern our daily vitality.

You may feel a pull towards the promise of knowledge, a chance to finally put a name to the fatigue that lingers or the subtle shifts in your body that you’ve been tracking privately. This feeling is a valid and deeply human response to an invitation to understand the self.

The prospect of a medical examination or a detailed questionnaire can feel like the first step on a path toward reclaiming a sense of control, offering a baseline understanding of the very hormones and metabolic signals that dictate your energy, mood, and overall function. It is a quest for personal data, the raw material from which a new chapter of well-being can be written.

This personal quest, however, unfolds within a framework of federal law designed to protect your autonomy. The primary governing principles are found within the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA). These laws establish clear boundaries to ensure that your participation in such a program is a choice, not a mandate.

An employer is permitted to ask questions about your health or request a medical examination only when it is part of a voluntary employee health program. The architecture of these regulations is built upon the foundational idea that your health data is profoundly personal.

The law seeks to create a space where you can engage with wellness initiatives without fear of penalty or discrimination, ensuring that the journey into your own biology is one you embark upon willingly, with full agency over your participation and your private information.

Federal laws like the ADA and GINA permit employer wellness programs to include medical exams only when participation is truly voluntary.

The Principle of Voluntary Participation

What transforms a corporate wellness initiative from a helpful resource into a source of anxiety is often the perception of pressure. The legal standard of “voluntary” participation is the safeguard meant to alleviate this concern. For a program to be considered voluntary, your employer cannot require you to participate.

Similarly, they are prohibited from denying you health coverage or taking any adverse employment action if you decide not to take part. This protection is absolute. It means that your decision to abstain from a biometric screening or to keep your health history private can have no bearing on your job security, your role, or your access to your primary health insurance.

The spirit of the law is to preserve your right to choose, making these programs an optional tool rather than a mandatory requirement.

A Framework for Understanding Your Body

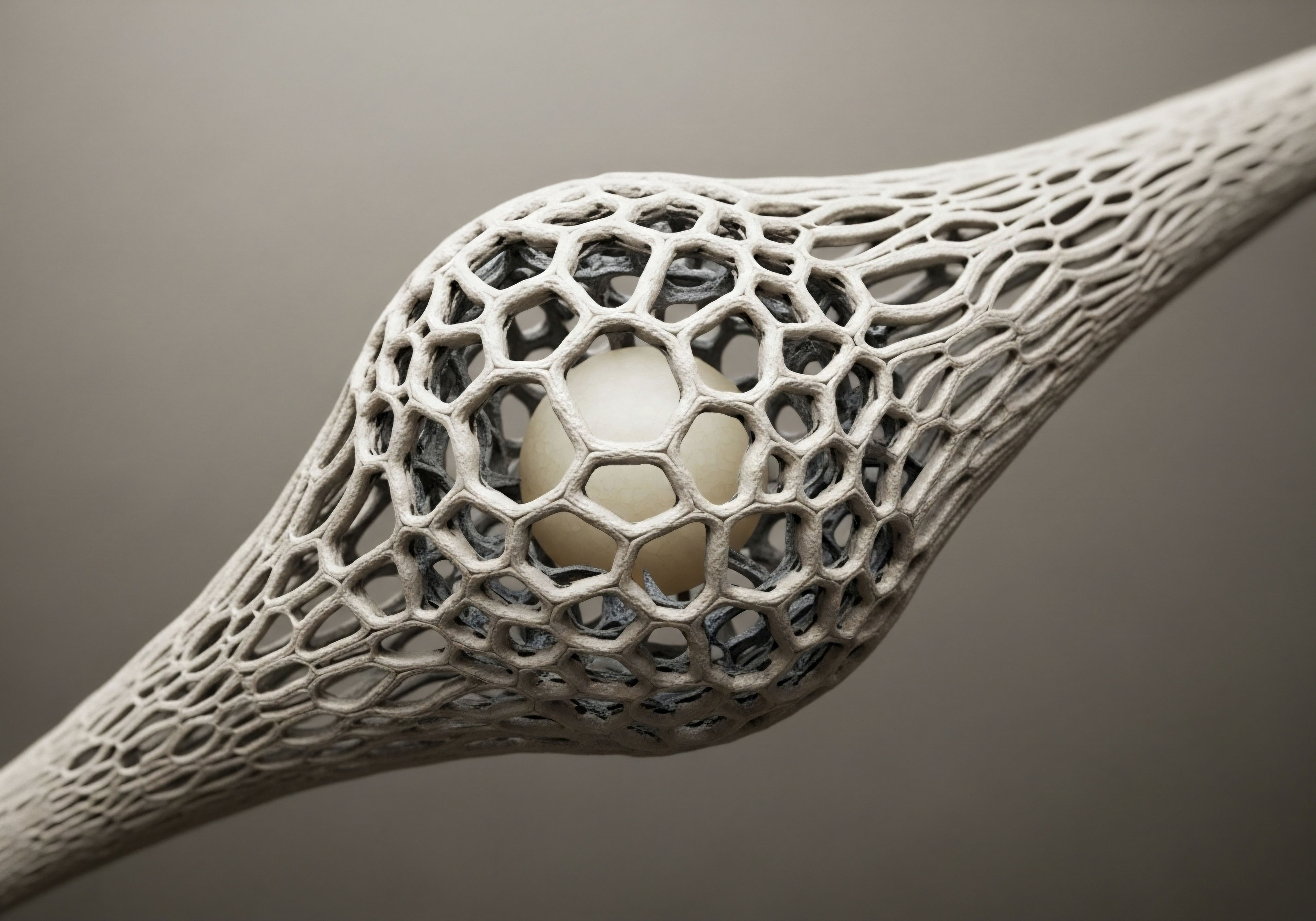

From a clinical perspective, the data points collected in a wellness screening can be the very beginning of a powerful journey. A simple blood panel can reveal preliminary information about metabolic health, such as glucose and lipid levels, which are intrinsically linked to the endocrine system.

These are the foundational markers that might later guide a more sophisticated investigation into hormonal balance, whether it concerns thyroid function, testosterone levels, or the complex interplay of hormones during perimenopause. Viewing the wellness program through this lens transforms it from a corporate requirement into a potential, albeit limited, portal.

It is an initial, wide-angle snapshot of your body’s internal environment, offering clues that you, in partnership with a knowledgeable clinician, can choose to investigate further. This is the empowering perspective ∞ using the opportunity to gather baseline data for your own purposes, on your own terms.

Intermediate

When an employer’s wellness program asks you to step beyond simple health pledges and into the realm of medical data, the legal framework becomes substantially more detailed. The regulations established by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) provide a specific blueprint for how these programs must operate to remain compliant with the ADA and GINA.

Understanding these details allows you to assess whether a program is a legitimate health-promotion tool or if it crosses critical legal and ethical boundaries. The two central pillars of a compliant program are that it must be “reasonably designed” and that the incentives offered cannot be coercive.

These stipulations are designed to create a clear, bright line between a program that genuinely seeks to support employee health and one that might function as a pretext for gathering sensitive information under duress.

What Does Reasonably Designed Mean?

For a wellness program that includes medical inquiries to be lawful, it must be more than a data-harvesting exercise. The “reasonably designed” standard requires the program to have a clear and demonstrable purpose related to promoting health or preventing disease.

This means the program should provide you with personalized feedback, follow-up information, or resources based on the results of your screening. A program that simply collects your blood pressure and cholesterol levels and reports them to you without context or next steps might not meet this standard.

However, a program that uses that data to provide you with a confidential health risk assessment, educational resources about cardiovascular health, or access to a health coach would likely be considered reasonably designed. The focus is on utility and support. The program should give something back to you ∞ knowledge, resources, or a plan ∞ in exchange for the data you provide.

A compliant wellness program must be structured to genuinely promote health, providing feedback and resources rather than simply collecting data.

Furthermore, the program cannot be overly burdensome. It should not require an unreasonable amount of your time, involve procedures that are excessively intrusive, or subject you to significant out-of-pocket costs. For individuals on a journey to understand their hormonal or metabolic health, this is a crucial protection.

A screening that provides foundational metabolic markers is one thing; a program demanding exhaustive and invasive testing without clear clinical justification would fail the “reasonably designed” test. The goal of the regulation is to ensure the program’s methods are proportional to its stated health-promotion goals.

The Complex Issue of Incentives

Perhaps the most contentious aspect of wellness programs is the use of incentives. While the ADA and GINA require programs to be voluntary, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) allows for incentives to encourage participation in programs that are part of a group health plan.

This created a legal gray area that the EEOC has attempted to clarify. To maintain the voluntary nature of a program, any reward for participating (or penalty for not participating) must not be so substantial that it becomes coercive. For years, a common guideline was that the incentive could not exceed 30% of the total cost of self-only health insurance coverage.

However, a court ruling invalidated that specific limit, leaving the landscape somewhat unsettled. Subsequent proposed rules, which were later withdrawn, suggested a move toward allowing only “de minimis” incentives, such as a water bottle or a gift card of modest value. Given this ambiguity, employers must be cautious.

For the employee, this means you should be aware that large financial incentives designed to compel you to share medical information exist in a legally sensitive space. The power dynamic is acknowledged by the law; a significant financial reward can feel less like an invitation and more like a requirement, undermining the principle of voluntary participation.

Data Confidentiality a Legal Mandate

The information gathered during a wellness screening is protected. Under the ADA, this medical information must be kept confidential. It should be stored separately from your personnel files, and your direct managers and supervisors should never have access to your individual results.

The law permits employers to receive information from their wellness programs only in an aggregate, anonymized format. For instance, an employer might receive a report stating that 30% of the workforce has high blood pressure, but it cannot receive a list of the specific employees who have that condition.

This firewall is critical. It ensures that the deeply personal data points that might illuminate your hormonal or metabolic status ∞ from A1c levels to lipid panels ∞ remain private, preventing their use in any decisions related to your employment, promotion, or responsibilities.

The table below outlines the key requirements for a wellness program that includes medical examinations or disability-related questions, drawing a clear line between permissible and impermissible practices.

| Feature | Compliant Program Requirements | Potential Violation |

|---|---|---|

| Participation |

Must be entirely voluntary. Employees can choose not to participate without any penalty or retaliation. |

Requiring participation to enroll in the company health plan or threatening adverse action for non-participation. |

| Program Goal |

Must be reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease, offering feedback or follow-up. |

Collecting data for its own sake without providing any health-related guidance or resources back to the employee. |

| Incentives |

Any financial or in-kind incentive must not be so large as to be coercive, compelling participation. |

An incentive so substantial that an employee feels they cannot afford to refuse participation. |

| Confidentiality |

Individual medical information is kept private and stored separately. Employer only receives aggregated, anonymous data. |

A manager receiving or having access to an individual employee’s specific screening results. |

| Notice |

Employees must receive a clear, understandable notice explaining what data is collected, how it’s used, and how it’s kept confidential. |

Failing to provide a notice or burying the details in complex, legalistic language. |

Academic

The legal architecture governing employer wellness programs represents a fascinating and dynamic intersection of public health policy, corporate finance, and individual civil rights. An academic examination of this topic reveals a fundamental tension between two competing philosophies ∞ a utilitarian view of population health management aimed at reducing aggregate healthcare expenditures, and a rights-based perspective prioritizing individual autonomy and data privacy.

The history of regulation and litigation in this area, particularly concerning the ADA’s “voluntary” clause, is a case study in the difficulty of reconciling these divergent aims. The core of the issue is an epistemological one ∞ who gets to ask the questions, who owns the resulting biological data, and how is that knowledge used to shape behavior and allocate resources?

The Evolving Definition of Voluntariness

The ADA itself prohibits employers from making disability-related inquiries or requiring medical examinations unless they are job-related and consistent with business necessity. A critical exception was carved out for “voluntary medical examinations. which are part of an employee health program.” The statute, however, did not define “voluntary,” creating a vacuum that the EEOC and the courts have struggled to fill for decades.

The EEOC’s 2016 regulations attempted to create a bright-line rule by tying the definition of voluntariness to the size of the financial incentive, pegging it at 30% of the cost of self-only coverage to harmonize with HIPAA’s framework.

This harmonization, while administratively convenient, was philosophically fraught. Critics argued that the ADA’s purpose was to prevent discrimination based on disability, while HIPAA’s was to regulate insurance. Applying an insurance-based incentive structure to a law designed to protect civil rights was seen as a category error.

This tension culminated in the 2017 case AARP v. EEOC, where the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia found that the EEOC had failed to provide a reasoned explanation for how a 30% incentive, which could amount to thousands of dollars, could be considered “voluntary” in any meaningful sense.

The court vacated the incentive limit rule, plunging the regulatory landscape back into uncertainty. This judicial intervention underscores a deep skepticism toward the use of significant financial instruments to elicit sensitive medical information, suggesting that true voluntariness requires the absence of substantial economic pressure.

What Is the Role of Hormonal Health in This Context?

From a systems-biology perspective, the data solicited by many wellness programs ∞ biometric screenings of blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, and BMI ∞ are lagging indicators of metabolic health. They are downstream effects of complex, upstream signaling processes governed by the endocrine system.

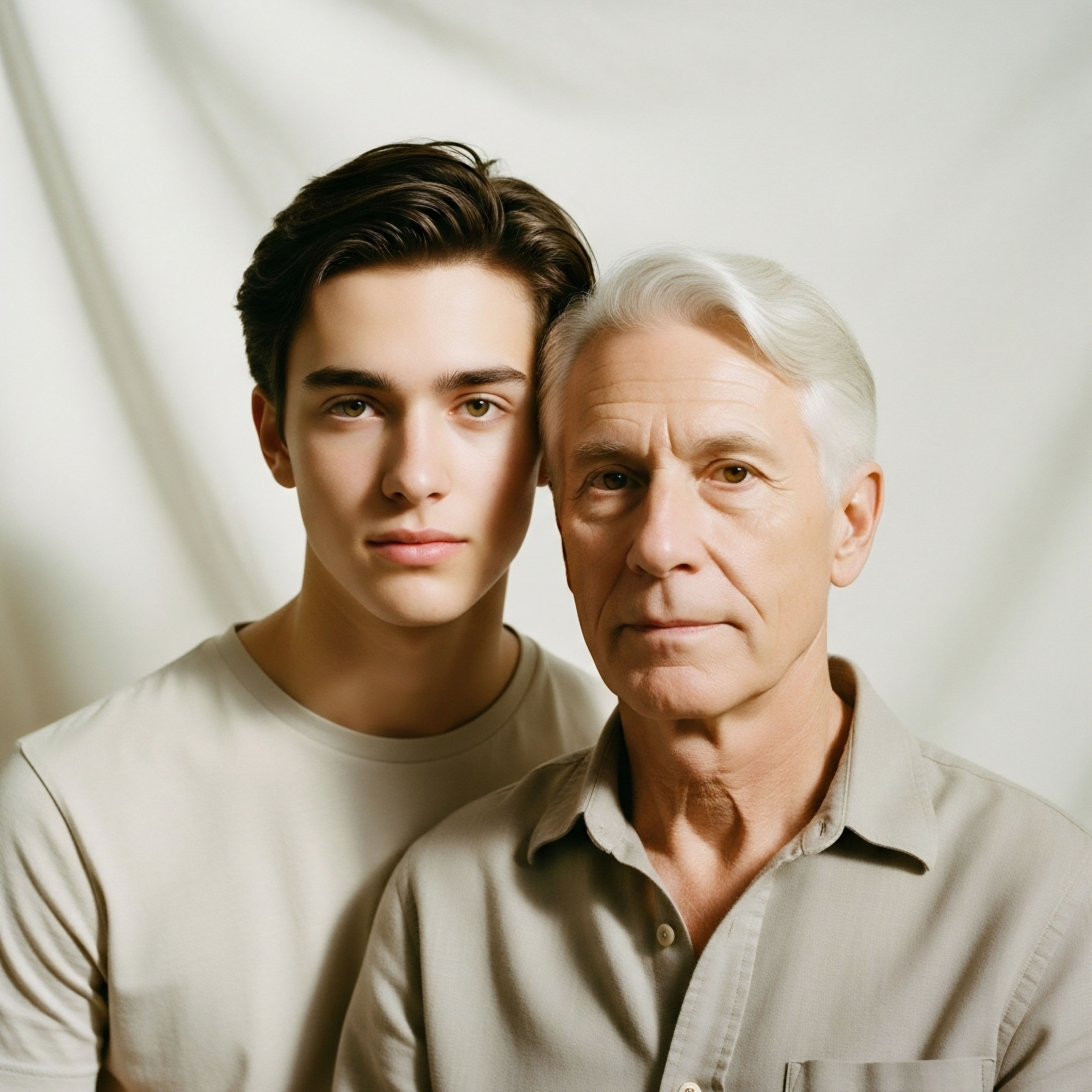

Chronic stress, for example, dysregulates the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to elevated cortisol, which in turn can drive insulin resistance and hypertension. Similarly, the decline of testosterone in men or the fluctuation of estrogen and progesterone in perimenopausal women has profound effects on metabolic function, body composition, and cardiovascular risk.

A wellness program that screens for high cholesterol without creating a pathway to investigate the underlying hormonal drivers is performing a superficial analysis. It identifies the smoke while ignoring the fire.

The legal ambiguity surrounding wellness program incentives reflects a deeper societal debate about the ethics of using financial pressure to access personal health data.

This creates a paradox. The very data that could serve as a starting point for a sophisticated, personalized health protocol ∞ one that might involve hormonal optimization or peptide therapies to address root causes ∞ is collected within a system that is legally and ethically constrained. The employer’s goal is risk stratification at the population level.

The individual’s need is a deep, personalized understanding of their unique biological system. The shallow, cross-sectional data from a typical wellness screening is often insufficient for the latter, yet the legal framework makes it difficult to implement a program with the necessary clinical depth while respecting the principles of voluntariness and data privacy.

Data Ownership and the Quantified Self

The debate over wellness programs can be situated within the broader cultural movement of the “quantified self,” where individuals leverage technology to track and analyze their own biological data. The legal framework struggles to keep pace. The ADA’s confidentiality requirements are robust, mandating that employers only receive aggregated data.

This is a crucial firewall. However, it does not address the secondary uses of this data by the third-party wellness vendors that employers contract with. These vendors amass vast datasets, which are invaluable for developing algorithms and population health models.

This raises profound questions about data ownership. When you participate in a wellness screening, you are providing raw material that has value far beyond your individual health assessment. You are contributing to a dataset that informs corporate health strategies, insurance product design, and public health research.

The legal framework, focused on preventing direct employer discrimination, is only beginning to grapple with the implications of this secondary data economy. The central academic and ethical challenge for the next decade will be to evolve our legal and social norms to ensure that as we pursue a more data-driven model of health, we do so in a way that preserves individual dignity, autonomy, and the fundamental right to control one’s own biological information.

The following table provides a high-level overview of the primary federal statutes that intersect to regulate employer wellness programs, highlighting their distinct objectives and requirements.

| Statute | Primary Objective | Key Requirement for Wellness Programs |

|---|---|---|

| Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) |

Prevent discrimination against individuals with disabilities. |

Programs with medical exams/inquiries must be voluntary and data kept confidential. |

| Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) |

Prevent discrimination based on genetic information. |

Prohibits requesting genetic information, with limited exceptions for voluntary wellness programs. |

| Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) |

Provide data privacy and security provisions for safeguarding medical information. |

Allows for defined financial incentives for health-contingent wellness programs that are part of a group health plan. |

- ADA ∞ This act’s primary function in this context is to ensure that an employee’s choice to participate or not is free from coercion and that their private health data cannot be used against them in an employment context.

- GINA ∞ This provides an additional layer of protection, specifically safeguarding genetic information (which can include family medical history) from being a condition of participation or a basis for incentives in most cases.

- HIPAA ∞ This law, particularly its nondiscrimination provisions, introduces the concept of permissible incentives, which created the central point of legal friction with the ADA’s “voluntary” standard.

References

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2016). Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Federal Register, 81(95), 31125-31155.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2016). Final Rule on GINA and Employer Wellness Programs. Federal Register, 81(95), 31143-31156.

- Jacobson, P. D. & Pomeranz, J. L. (2018). A legal and public health assessment of the new EEOC wellness rules. The Milbank Quarterly, 96 (1), 55 ∞ 81.

- Fowler, E. F. & Porter, G. (2017). Workplace Wellness Programs and the Americans With Disabilities Act. JAMA, 317 (11), 1121 ∞ 1122.

- AARP v. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 267 F. Supp. 3d 14 (D.D.C. 2017).

- Matthews, S. C. (2021). Navigating the Legal Morass of Workplace Wellness Programs. American Bar Association.

- Ledbetter, J. (2020). Workplace Wellness Programs ∞ A Legal Guide for Employers. Nolo.

Reflection

Where Does Your Personal Health Journey Begin?

You have now navigated the complex legal terrain that surrounds a seemingly simple question. The rules, regulations, and court cases provide a critical framework for protection, yet they exist outside of you. The true journey is internal. The data points on a screening report are just that ∞ points.

They are echoes of a deeper biological conversation happening within your body at every moment. The knowledge that a program must be voluntary, that your privacy is protected, and that its design must be reasonable should not be an endpoint. It is the clearing of a path.

It grants you the freedom to decide if and how you will engage. What will you do with that freedom? Perhaps the ultimate purpose of these external rules is to give you the quiet, unpressured space to listen to your own internal signals and to decide, with clinical guidance, what questions are truly worth asking about your own health.