Fundamentals

The question of whether an employer can use aggregated wellness data to alter health insurance offerings touches upon a deeply personal aspect of our lives our health. It moves the conversation from the communal to the individual, examining how population-level data reflects on the well-being of each person contributing to it.

The process begins when employers, seeking to foster a healthier workforce and manage insurance costs, implement wellness programs. These initiatives often collect health information through assessments, biometric screenings, or fitness trackers. Your participation, while presented as voluntary, may be tied to financial incentives, creating a complex dynamic of choice and pressure.

This collected information is then aggregated and de-identified, a process designed to strip out personal details and present a collective health snapshot of the workforce. Federal laws, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), establish strict rules for this process.

The core principle of these regulations is to create a firewall between your individual health data and your employer. In theory, your employer should only see a high-level summary, such as the percentage of employees with high blood pressure, not a list of names. This aggregated data provides insights into the collective health risks and needs of the employee population.

A primary function of data aggregation in wellness programs is to provide employers with a high-level view of workforce health without exposing individual identities.

With this aggregated health profile, an employer and its insurance partners can begin to make strategic decisions. The data might reveal a high prevalence of stress-related conditions, for example, prompting the introduction of enhanced mental health support and mindfulness resources into the insurance plan.

Conversely, a low incidence of smoking might lead to the reduction or elimination of costly cessation programs. The goal, from the employer’s perspective, is to tailor the health plan to the specific needs of its workforce, potentially leading to more effective care and better cost control. This data-driven approach allows for the customization of benefits, moving away from a one-size-fits-all model to one that reflects the documented health trends within the organization.

The legal framework surrounding this practice is intricate. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) further clarified HIPAA’s nondiscrimination rules, allowing for wellness program incentives within certain limits. These laws attempt to balance the employer’s interest in promoting health and managing costs with the employee’s right to privacy and protection from discrimination.

The central tenet is that the programs must be reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease, not to be a subterfuge for shifting costs or discriminating against individuals. The effectiveness and fairness of this balance, however, remain subjects of ongoing debate and regulatory scrutiny, leaving employees to navigate a system where their personal health data contributes to the very structure of the benefits they receive.

Intermediate

The mechanisms allowing aggregated wellness data to influence health insurance offerings are rooted in a series of interconnected federal regulations. At the forefront are HIPAA, the ACA, and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Together, these laws construct a regulatory environment where data can be used to inform plan design, provided that stringent privacy and nondiscrimination protocols are followed.

An employer does not receive raw, identifiable health data. Instead, a third-party wellness vendor or the health plan itself processes the information, aggregating it into statistical summaries. This aggregated data is what the employer uses to understand the health profile of its workforce and make informed decisions about insurance benefits.

How Is Wellness Data Translated into Insurance Plan Design?

The translation of aggregated data into tangible changes in health insurance offerings is a multi-step process. It begins with the analysis of the collective data to identify prevalent health risks and trends. For instance, if data reveals high rates of pre-diabetes, an employer might work with their insurer to enhance coverage for diabetes prevention programs, nutritional counseling, and continuous glucose monitoring systems.

This proactive approach is framed as a benefit to both parties the employee gains access to preventative care, and the employer potentially mitigates future high-cost claims related to chronic disease.

Aggregated health data allows employers to strategically adjust insurance benefits, aligning them with the most prevalent health needs of their employee population.

This strategic adjustment of benefits is a core component of what the industry refers to as “value-based” insurance design. The central idea is to lower barriers to high-value services for chronically ill individuals by reducing or eliminating copayments for necessary medications and services.

The aggregated data identifies which services are of highest value to that specific employee population, allowing for a more targeted and potentially more effective allocation of resources. The table below illustrates how specific data points can lead to concrete changes in an insurance plan.

| Aggregated Data Point | Potential Insurance Plan Modification |

|---|---|

| High prevalence of musculoskeletal issues | Expanded coverage for physical therapy, chiropractic care, and ergonomic assessments. |

| Significant percentage of employees reporting high stress | Addition of mental health apps, increased number of covered therapy sessions, and stress management programs. |

| Low rates of preventative screenings (e.g. mammograms, colonoscopies) | Implementation of a rewards program offering premium reductions for completing age-appropriate screenings. |

| Widespread vitamin D deficiency identified in biometric screenings | Inclusion of vitamin D testing and supplements in preventative care benefits. |

The Role of Financial Incentives

Financial incentives are a powerful tool used to encourage participation in wellness programs. Under the ACA, these incentives can be substantial, reaching up to 30% of the total cost of health coverage. This financial leverage raises questions about the “voluntary” nature of these programs.

When faced with a significant financial penalty for non-participation, an employee may feel compelled to share health information they would otherwise prefer to keep private. This dynamic is a point of contention, with critics arguing that it can be coercive and disproportionately affect lower-wage workers.

The structure of these incentives can take several forms:

- Participation-Based Incentives These are rewards given simply for completing a health-related activity, such as a health risk assessment or biometric screening. The outcome of the screening does not affect the reward.

- Outcome-Based Incentives These are rewards tied to achieving specific health goals, such as lowering cholesterol or quitting smoking. These programs must offer a reasonable alternative standard for individuals who cannot meet the goal due to a medical condition.

The use of outcome-based incentives is particularly complex. While intended to motivate healthy behaviors, they can be perceived as punitive to those with chronic conditions or genetic predispositions. The legal and ethical tightrope that employers must walk involves designing programs that are genuinely aimed at improving health without penalizing individuals for factors that may be beyond their control. The ongoing evolution of regulations from agencies like the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) reflects the difficulty in striking this balance.

Academic

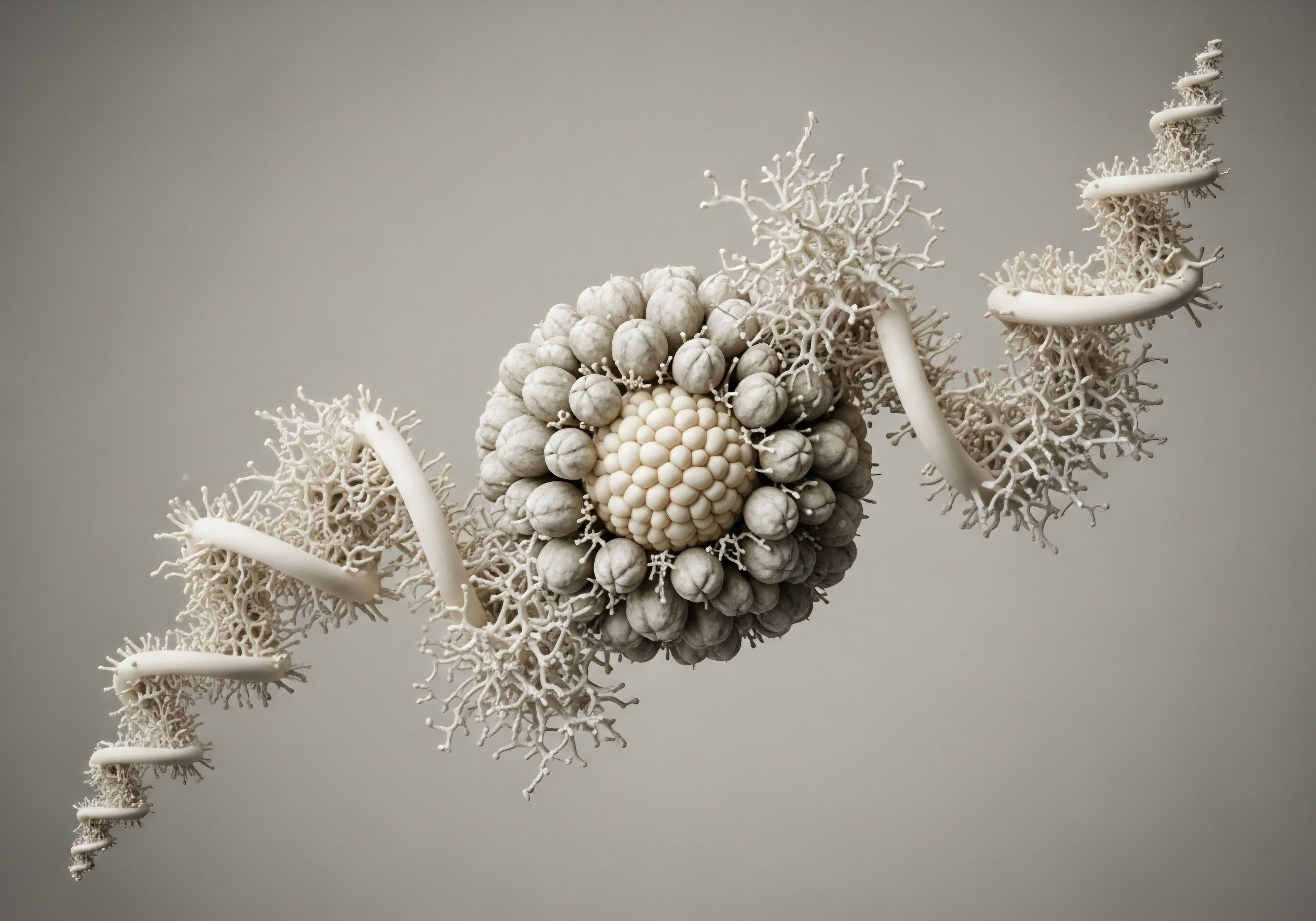

The utilization of aggregated wellness data in the formulation of employer-sponsored health insurance plans represents a complex intersection of public health objectives, corporate finance, and bioethical principles. From a systems-biology perspective, this practice can be viewed as an attempt to create a feedback loop between the collective physiological state of a population and the healthcare resources allocated to it.

The data, in essence, becomes a diagnostic tool for the organization, allowing for a targeted intervention in the form of a customized insurance benefits package. This approach, however, is predicated on the assumption that the aggregated data is an accurate and unbiased representation of the population’s health, an assumption that warrants critical examination.

What Are the Methodological Limitations of Aggregated Data?

The process of data aggregation, while designed to protect individual privacy, is not without its methodological limitations. The de-identification process itself can, in some cases, be reversed, particularly in smaller organizations where the pool of employees is limited. Furthermore, the data collected is often from a self-selecting group of participants.

Employees who are already healthy may be more inclined to participate in wellness programs, leading to a skewed representation of the overall workforce’s health. This can result in a “healthy user bias,” where the aggregated data paints a rosier picture than reality, potentially leading to the underfunding of services for those who need them most.

The ethical framework for the collection and use of this data is a subject of considerable debate. The principle of informed consent is central to this discussion. While employees may sign a consent form, the extent to which they truly understand how their data will be used and the potential long-term implications is questionable.

The power imbalance inherent in the employer-employee relationship complicates the notion of voluntary participation. When non-participation comes with a significant financial cost, the decision to share personal health information cannot be considered entirely uncoerced.

The ethical integrity of using aggregated wellness data hinges on the robustness of informed consent and the impossibility of re-identifying individuals from the dataset.

The Interplay of Legal Frameworks

The legal landscape governing this practice is a patchwork of federal statutes that often have competing interests. HIPAA’s Privacy Rule is designed to protect personal health information, but it includes provisions that allow for the use of de-identified data for research and health plan operations.

The ADA prohibits discrimination based on disability, yet it allows for voluntary medical examinations as part of an employee health program. GINA was enacted to prevent discrimination based on genetic information, but it contains exceptions for wellness programs that meet certain requirements.

The tension between these laws creates a gray area that employers and wellness vendors must navigate carefully. The EEOC has attempted to provide clarity through rulemaking, but these efforts have been subject to legal challenges and shifts in administrative priorities. The result is a state of legal uncertainty that can leave both employers and employees vulnerable. The table below outlines the primary federal statutes and their key provisions related to wellness programs.

| Statute | Primary Function and Relevance to Wellness Data |

|---|---|

| HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) | Establishes national standards for the protection of individually identifiable health information. It permits the use of de-identified, aggregated data for health plan design and operations. |

| ACA (Affordable Care Act) | Amended HIPAA to allow for significant financial incentives (up to 30% of the cost of coverage) for participation in wellness programs, codifying their role in the health insurance marketplace. |

| ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) | Prohibits employment discrimination based on disability. It allows for voluntary medical inquiries and exams as part of a wellness program, provided they are reasonably designed to promote health. |

| GINA (Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act) | Prohibits discrimination based on genetic information in health insurance and employment. It allows for the collection of genetic information in wellness programs only with knowing, voluntary, and written consent. |

Ultimately, the question of whether employers can use aggregated wellness data to change their health insurance offerings is not just a legal or financial one; it is a question about the future of public health and the role of the workplace in promoting well-being.

While the potential for data-driven, preventative care is significant, so too is the potential for a new form of digital discrimination, where group statistics are used to make decisions that have a profound impact on individuals. The long-term consequences of this trend will depend on the strength of our legal and ethical safeguards, and our collective commitment to ensuring that these programs serve to genuinely improve health rather than simply shift costs.

References

- Apex Benefits. “Legal Issues With Workplace Wellness Plans.” 31 July 2023.

- Kane, Jason. “Feds cap how much sensitive medical data employers can collect through wellness programs.” PBS News, 17 May 2016.

- Prabhu, A. V. “Health and Big Data ∞ An Ethical Framework for Health Information Collection by Corporate Wellness Programs.” The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, vol. 44, 2016, pp. 474-480.

- Jacobson, P. D. and K. P. Tutundjian. “Health Risk Reduction Programs in Employer-Sponsored Health Plans ∞ Part II ∞ Law and Ethics.” Preventing Chronic Disease, vol. 6, no. 2, 2009, A42.

- Brin, Dinah Wisenberg. “Wellness Programs Raise Privacy Concerns over Health Data.” SHRM, 6 April 2016.

Reflection

Your Data in the Collective

Having explored the mechanisms and regulations, the central question returns to a personal level. Your health data, when aggregated, tells a story about the collective well-being of your workplace. It informs decisions that shape the very fabric of the health benefits available to you and your colleagues.

This knowledge positions you at a new vantage point. You are not merely a passive recipient of a benefits package but an active, albeit anonymized, contributor to its design. Consider the implications of this role. How does the awareness that your health trends contribute to the larger picture influence your perspective on wellness programs and the data they collect?

The journey from individual data point to collective health strategy is a complex one, filled with both potential and peril. Understanding this journey is the first step toward navigating it with intention and advocating for a system that is both effective and equitable.

Glossary

health insurance offerings

aggregated wellness data

financial incentives

health information

genetic information nondiscrimination act

health insurance

aggregated data

health data

health plan

affordable care act

americans with disabilities act

wellness data

wellness programs

health risk assessment

outcome-based incentives

bioethical principles

personal health information