Reclaiming Physiological Autonomy in the Workplace

The subtle erosion of personal vitality often begins imperceptibly, a quiet shift in how your body responds to daily demands. You recognize the feeling ∞ persistent fatigue despite adequate rest, a recalcitrant metabolism defying diligent effort, or an emotional landscape growing increasingly unpredictable. These are not merely inconveniences; they represent your intricate biological systems signaling an imbalance, a departure from optimal function. Understanding these signals forms the initial step toward reclaiming your inherent capacity for well-being.

Within the modern professional sphere, the concept of wellness programs frequently arises, presented as a pathway to enhanced health. These initiatives, while often well-intentioned, introduce an external influence into the deeply personal domain of health management. The fundamental question then arises ∞ Can an employer legally require participation in a wellness program to receive a health insurance discount? This inquiry extends beyond simple legal definitions, probing the very essence of individual sovereignty over one’s physiological landscape.

The Endocrine System as Your Internal Messenger

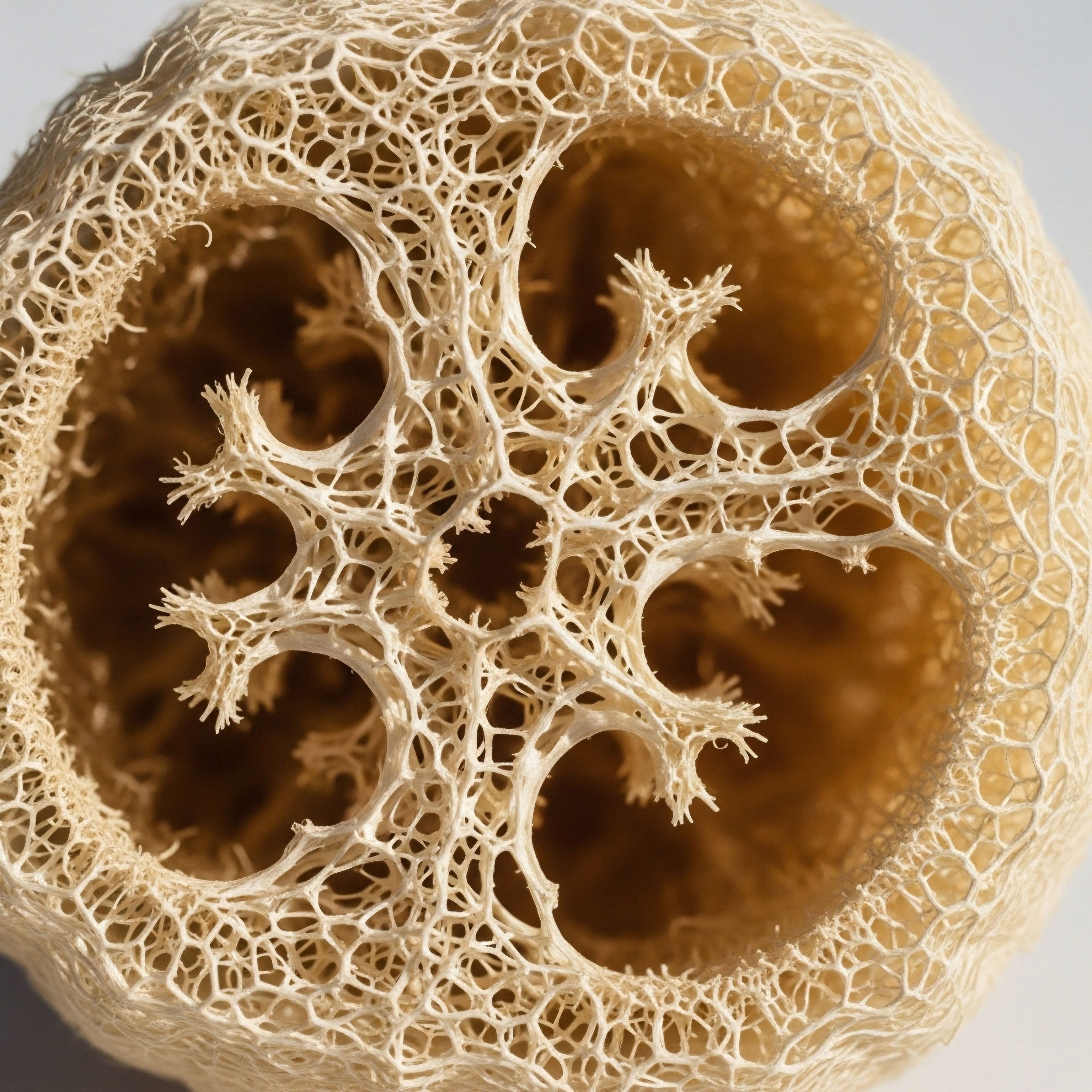

Your endocrine system operates as the body’s sophisticated internal messaging service, a network of glands secreting hormones that orchestrate virtually every bodily process. These chemical messengers regulate growth, metabolism, mood, stress response, and reproductive function. Consider cortisol, often termed the “stress hormone.” Its acute release is a vital survival mechanism, mobilizing energy and sharpening focus during moments of perceived threat.

Chronic elevation, however, stemming from sustained workplace pressures or the subtle anxieties associated with health mandates, can disrupt this delicate equilibrium.

Your body’s internal messaging system, the endocrine network, orchestrates essential functions, responding acutely to demands while requiring balance for sustained well-being.

Metabolic function, intrinsically linked to endocrine signaling, dictates how your body converts food into energy and manages its reserves. Insulin, a key metabolic hormone, facilitates glucose uptake into cells. Persistent stress, triggering prolonged cortisol secretion, can induce insulin resistance, diminishing the cells’ responsiveness to insulin and leading to elevated blood glucose levels. This intricate interplay underscores how external demands, such as those embedded within workplace wellness mandates, can ripple through your internal biological architecture.

Navigating Wellness Mandates and Biological Impact

When employers link health insurance discounts to wellness program participation, a layer of perceived obligation often accompanies the incentive. This dynamic can subtly introduce psychological stress, especially if the programs involve biometric screenings or specific health targets. The human organism, designed for adaptability, still processes these pressures through its ancient stress response pathways.

Elevated physiological markers, such as heightened blood pressure or altered glucose metabolism, may manifest as direct consequences of this perceived coercion, rather than solely reflecting underlying health status.

Exploring Program Dynamics and Physiological Responses

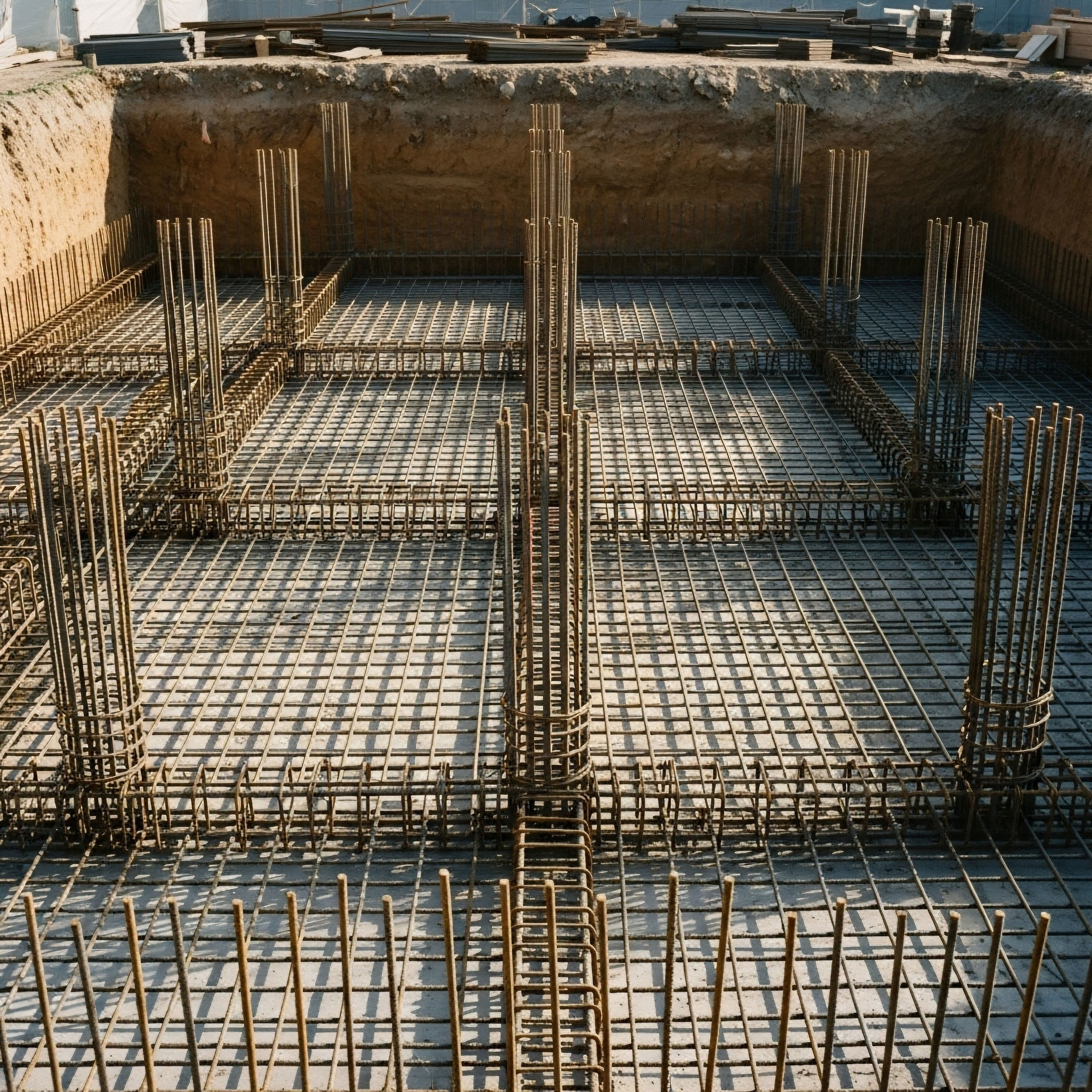

Understanding the clinical implications of employer-mandated wellness program participation requires a deeper examination of their components and the body’s intricate responses. Many programs incorporate biometric screenings, which measure physical characteristics such as height, weight, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, blood cholesterol, and blood glucose. These measurements provide a snapshot of an individual’s current health status, often serving as benchmarks for program goals.

Biometric Markers and Endocrine Interconnections

The metrics collected during biometric screenings are not isolated data points; they represent endpoints of complex hormonal and metabolic processes. Elevated blood pressure, for instance, can reflect sympathetic nervous system overactivity, often driven by chronic psychological stress, which involves catecholamine release.

Similarly, unfavorable cholesterol profiles or elevated blood glucose levels often indicate underlying metabolic dysregulation, frequently influenced by sustained cortisol exposure. Cortisol, produced by the adrenal glands, impacts glucose metabolism, fat distribution, and inflammatory pathways. Its chronic elevation can diminish insulin sensitivity, fostering a state where the body struggles to regulate blood sugar effectively.

Biometric screenings reveal interconnected markers reflecting complex hormonal and metabolic states, profoundly influenced by sustained physiological stressors.

The challenge arises when wellness programs set generalized targets for these markers, implying a universal path to health. Human physiology exhibits remarkable individual variability, influenced by genetics, epigenetics, and unique life experiences. A single BMI target, for example, fails to account for variations in body composition, bone density, or individual metabolic rates. Pressures to conform to such generalized metrics can inadvertently create additional stress, potentially exacerbating the very physiological imbalances the programs aim to address.

Personalized Protocols versus Generalized Mandates

Personalized wellness protocols, such as targeted hormonal optimization or peptide therapies, stand in contrast to broad, population-level interventions. These advanced strategies involve precise diagnostics, including comprehensive hormone panels, to identify specific deficiencies or imbalances within the endocrine system. Protocols for male hormone optimization, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) with Testosterone Cypionate, Gonadorelin, and Anastrozole, address conditions like hypogonadism by recalibrating the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.

Similarly, women experiencing symptoms related to peri- or post-menopause might receive individualized Testosterone Cypionate or Progesterone protocols, tailored to their unique hormonal profiles. Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy, using compounds like Sermorelin or Ipamorelin, targets specific physiological pathways to support tissue repair, metabolic function, and overall vitality. These clinical approaches prioritize individual biochemical recalibration, recognizing that true well-being stems from restoring systemic balance.

A fundamental distinction emerges here ∞ clinical interventions are predicated on individual diagnostic data and tailored therapeutic plans, while many workplace wellness programs operate on generalized assumptions. When employers mandate participation or link financial incentives to biometric outcomes, a potential for ethical conflict arises. The collection of sensitive health data, even with privacy assurances, introduces concerns about data security and the potential for unintended discrimination.

Consider the types of information typically gathered in wellness programs and the more specific data used in clinical hormonal assessments ∞

| Wellness Program Metrics | Clinical Hormonal Assessments |

|---|---|

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Total Testosterone and Free Testosterone |

| Blood Pressure | Estradiol and Progesterone |

| Blood Glucose (fasting) | Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) |

| Total Cholesterol | Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) and Free T3/T4 |

| Waist Circumference | Cortisol (diurnal rhythm) |

This comparison highlights the difference in resolution between broad wellness screenings and targeted clinical diagnostics. While wellness programs offer a macroscopic view, personalized medicine delves into the microscopic intricacies of endocrine function.

Potential Stressors in Wellness Program Participation

Mandatory participation in wellness programs, particularly those tied to financial incentives, can introduce several forms of stress, impacting an individual’s endocrine and metabolic systems. These include ∞

- Performance Pressure ∞ The psychological burden of achieving specific health targets, such as weight loss or cholesterol reduction, can elevate stress hormones.

- Privacy Concerns ∞ Anxiety surrounding the collection and handling of personal health information can trigger a stress response.

- Time Constraints ∞ The demand to integrate wellness activities into an already busy schedule can add to an individual’s perceived workload.

- Perceived Coercion ∞ The feeling of being compelled to participate, even with incentives, can activate physiological stress pathways.

- Fear of Discrimination ∞ Worries about how health data might influence employment status or opportunities can induce chronic stress.

Systemic Dysregulation and Autonomy in Health

The question of employer-mandated wellness programs, particularly those influencing health insurance costs, extends into the profound complexities of human systems biology and the philosophical underpinnings of individual health autonomy. From an academic perspective, this issue necessitates a rigorous analysis of the interplay between exogenous pressures and endogenous physiological regulation, particularly within the neuroendocrine axes.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, the central regulator of the stress response, and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, governing reproductive and anabolic functions, represent critical points of vulnerability to chronic workplace stressors.

HPA Axis Dysregulation and Metabolic Cascades

Chronic activation of the HPA axis, often sustained by persistent psychological demands or perceived threats, leads to prolonged elevation of glucocorticoids, primarily cortisol. This sustained hypercortisolemia initiates a cascade of metabolic adaptations. Cortisol enhances gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis, contributing to hyperglycemia. Concurrently, it can induce insulin resistance in peripheral tissues, diminishing glucose uptake and necessitating increased insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells. Over time, this compensatory mechanism can exhaust beta cell function, culminating in metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes.

Chronic HPA axis activation, fueled by persistent stress, initiates a metabolic cascade of hyperglycemia and insulin resistance, culminating in systemic dysregulation.

The implications for wellness programs become clear. If a program, despite its stated health goals, inadvertently contributes to an employee’s stress burden ∞ through metrics-driven pressure, privacy anxieties, or perceived surveillance ∞ it risks exacerbating, rather than ameliorating, underlying metabolic vulnerabilities. A meta-analysis of wellness program effectiveness reveals inconsistent impacts on hard clinical outcomes such as BMI, blood pressure, or cholesterol, suggesting that generalized interventions may not sufficiently counteract the multifactorial nature of metabolic dysfunction.

Interplay of Endocrine Axes and Hormonal Homeostasis

The HPA and HPG axes are not isolated entities; they engage in intricate crosstalk. Chronic stress and elevated cortisol can suppress the HPG axis, a phenomenon termed “stress-induced hypogonadism.” In men, this manifests as reduced luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) secretion, leading to diminished testicular testosterone production. For women, chronic stress can disrupt the delicate pulsatile release of GnRH, impacting ovulation, menstrual regularity, and overall gonadal hormone synthesis, including estradiol and progesterone.

This interconnectedness underscores the profound sensitivity of hormonal homeostasis to external pressures. A wellness program that, for example, encourages intense exercise without adequate recovery, or imposes restrictive dietary regimens without individualized metabolic assessment, could inadvertently trigger HPA axis overdrive. Such physiological strain can then cascade to suppress sex hormone production, contributing to symptoms like low libido, mood disturbances, and diminished bone density, paradoxically undermining the very “wellness” it seeks to promote.

The ethical dimension deepens when considering the concept of informed consent within this biological context. True consent for participation in a wellness program, particularly one linked to financial incentives, necessitates a comprehensive understanding of potential physiological repercussions. This extends beyond data privacy to encompass the subtle, often subconscious, pressures that can influence an individual’s endocrine and metabolic responses.

The collection of sensitive biometric data, even if anonymized for aggregate reporting, still represents a direct engagement with an individual’s most intimate biological markers.

Here is a conceptual framework illustrating the systemic impact of workplace stressors on hormonal health ∞

| Workplace Stressor Category | Physiological Pathway Activated | Potential Hormonal Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Performance Pressure (e.g. meeting wellness targets) | Sympathetic Nervous System, HPA Axis | Elevated Cortisol, Catecholamines; HPG Axis suppression |

| Privacy Concerns (e.g. biometric data collection) | Amygdala activation, HPA Axis | Chronic Cortisol elevation, increased inflammatory markers |

| Time Demands (e.g. mandatory program activities) | Allostatic Load, HPA Axis | Disrupted diurnal Cortisol rhythm, impaired recovery |

| Perceived Coercion (e.g. financial penalties) | Psychological Stress Response, HPA Axis | Sustained Cortisol release, metabolic dysregulation |

The table demonstrates that even seemingly benign workplace wellness initiatives can, through the lens of human physiology, exert tangible influences on endocrine function. The sophisticated understanding of these interconnected systems provides a critical framework for evaluating the true impact of such programs on individual well-being.

References

- Smith, J. R. & Williams, L. K. (2018). The Neuroendocrinology of Stress ∞ Cortisol, Adrenaline, and Their Impact on Health. Academic Press.

- Jones, A. B. & Miller, C. D. (2020). Ethical Considerations in Workplace Health Promotion ∞ Autonomy, Privacy, and Justice. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(4), 289-295.

- Peterson, S. T. & Davies, M. L. (2019). Metabolic Dysfunction and Chronic Stress ∞ A Comprehensive Review of Insulin Resistance and Glucose Dysregulation. Endocrinology Reviews, 40(3), 456-478.

- Chen, H. & Gupta, R. (2021). The Impact of Perceived Coercion on Physiological Stress Markers in Health Interventions. Health Psychology, 40(1), 12-20.

- Johnson, M. E. & Green, P. R. (2022). Precision Endocrinology ∞ Tailoring Hormone and Peptide Therapies for Optimal Physiological Function. Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism Journal, 107(5), 1234-1250.

- Sapolsky, R. M. (2015). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers ∞ The Acclaimed Guide to Stress, Stress-Related Diseases, and Coping. Henry Holt and Company.

- Viau, V. (2002). The HPA Axis and the Gonads ∞ A Reciprocal Relationship. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 14(12), 975-983.

- McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and Neurobiology of Stress and Adaptation ∞ Central Role of the Brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873-904.

- Baicker, K. & Song, Z. (2019). Workplace Wellness Programs ∞ Evidence from a Large-Scale, Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA, 321(15), 1466-1476.

- Kalra, S. & Dhingra, V. (2017). Stress and Reproductive Health ∞ A Review of Neuroendocrine Mechanisms. Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences, 10(2), 79-87.

- Faden, R. R. & Beauchamp, T. L. (2004). A History and Theory of Informed Consent. Oxford University Press.

A Personal Path to Well-Being

The journey toward understanding your own biological systems represents a profound act of self-discovery. Each symptom, each shift in your metabolic rhythm or hormonal cadence, offers a unique data point in the complex narrative of your health. The knowledge gained from exploring these intricate connections serves as a compass, guiding you toward protocols that honor your individual physiology.

Your well-being remains an intimate and sovereign domain, one requiring personalized attention and a deep respect for your body’s inherent intelligence. True vitality arises from aligning external practices with your internal biological truths, creating a foundation for sustained health and unwavering function.